EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The Covid-19 pandemic has impacted men and women differently. While infection rates and mortality rates are higher among men, it is women who are more negatively affected where socio-economics and personal security are concerned.

- The lockdowns and movement restriction orders for containing the pandemic of Covid-19 have resulted in a global rise of domestic violence. As tensions and tempers escalate, cases of physical or psychological abuse have become more frequent.

- Since the MCO period began, the number of calls to helplines in relation to domestic abuse has been increasing in Malaysia, and in Penang. The second phase of the MCO saw an escalation in the severity of the cases of abuse.

- The MCO has also made it more difficult for victims of domestic abuse to call a helpline due to cramped living situation at home.

- Immediate measures are needed to protect victims of domestic violence, and domestic violence support services may need to be classed as an essential service.

- In the longer term, various forms of support group services will need to be developed by the government, NGOs and other key actors in society.

INTRODUCTION

The pandemic of Covid-19 has impacted the world in ways that are unprecedented. Temporary movement restriction orders (termed as the Movement Control Order [MCO] in Malaysia) being imposed by governments have the expected consequence of pushing the world economy towards a recession. The closing of non-essential businesses and services has reduced economic activity tremendously.

Every individual, in one way or another, has been negatively affected. Low-income groups in particular are heavily affected, with food security and sanitisation being two of the primary problems they face. Workers suffer drops in income and even unemployment. The hospitality and tourism sector, in particular, most broadly hit. Then there are the informal and self-employed workers who are unable to generate any income at all during the lockdowns.

Above all else, the social isolation and the accompanying loss of personal sense of freedom has also brought on an increase in mental health issues, more so for those who are already suffering from mental disorders to begin with.

COVID-19 THROUGH A GENDER LENS

From a gender perspective, the pandemic is affecting men and women in markedly different ways. In terms of infection rate and mortality rate, Global Health 50/50[1] has found that, for countries that collect sex-disaggregated data, the proportion of positive Covid-19 cases is higher in males than in females. Concurrently, the death rates for males are decidedly higher than for females. For example, Spain reported that 63% of Covid-19-related deaths are males. Other countries show a similar trend.[2] One of the cited reasons for this is that the disease is more deadly for those with pre-existing medical conditions, and the number of men with hypertension as well as cardiovascular and pulmonary conditions are disproportionately higher than among women.[3] In Malaysia, males made up approximately 75.0% of Covid-19 deaths, with the Health Director-General suggesting that men have a higher chance of infection due their more frequent involvement in outdoor activities.[4]

In contrast, when it comes to socioeconomic and personal security, women are unequivocally more affected. Gender inequalities and discriminatory social norms seem to have intensified in the current climate. The risk of unemployment will be higher for women, as the percentage of women working in the heavily Covid-19 affected service subsectors, such as textile and garment manufacturing, hospitality, tourism and so on, is higher than of men.[5]

Additionally, with society’s customary gender pay gap, women are projected to suffer more heavily in financial terms.[6] With the closure of schools and child care centres, women have to bear the extra burden of child care at home more so than men, as social norms dictate them to be the primary caregivers. The situation gets much worse for single mothers who work in an essential sector.

However, one of the biggest problems for policy makers to consider during the pandemic is the threat against women’s physical and emotional safety in the home.

THE GLOBAL RISE IN DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

Domestic violence refers to patterns and actions of aggressive and abusive behavior committed by one spouse or partner against the other within an intimate relationship, for the purpose of gaining power and control.[7] The type of abuse can take many forms – beyond being physical abuse, it is also psychological, emotional, sexual or economic abuse. And an overwhelming majority of the victims and survivors are women.

Studies have shown that instances of domestic violence increases when families are together for extended periods of time, for example, during festive or holiday seasons.[8] The current lockdown and stay-at-home orders trap domestic violence survivors in the same confines as their abuser, with little options for escape. With the pandemic raging outside, survivors also tend to believe that they are nevertheless safer at home.

In the United States of America, the National Domestic Violence Helpline received more than 2,000 calls in cases of abuse relating to the pandemic.[9] A majority of the callers are essential workers whose partners had tried to physically stop them from going to work. Australia has seen a 75% increase in Google searches relating to domestic violence, although the number of calls has not increased.[10]

China saw a tripling of domestic violence cases in Hubei in February, in comparison to the previous year, and Beijing’s national family helpline reported a 50% increase in domestic abuse calls during the lockdown.[11] In Spain, crisis calls increased by 12.4% in the first two weeks of the lockdown, and an alarming 270% increase in online consultations was recorded.[12] An even more disturbing scenario was seen in the UK, where there were 16 domestic violence deaths recorded between 23 March and 12 April.[13] For the same period, the average had been five deaths over the last ten years. The United Nations is calling for global action to bring the surge in domestic violence under control.

As clearly seen, this pattern is a global trend, and unfortunately, Malaysia is no exception.

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE IN MALAYSIA AND PENANG

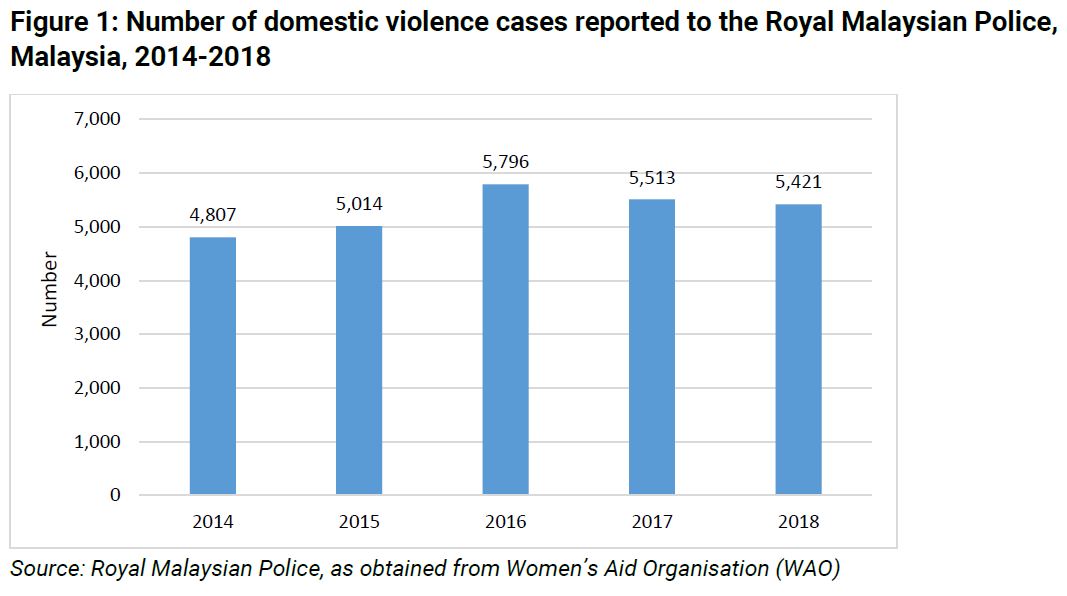

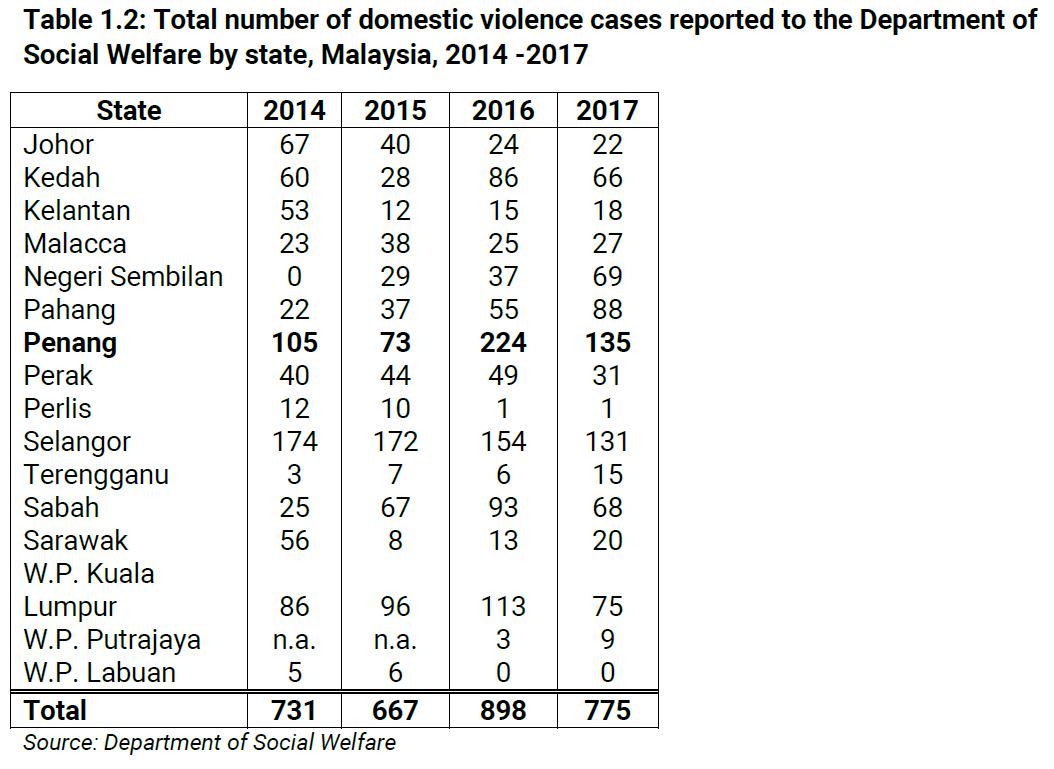

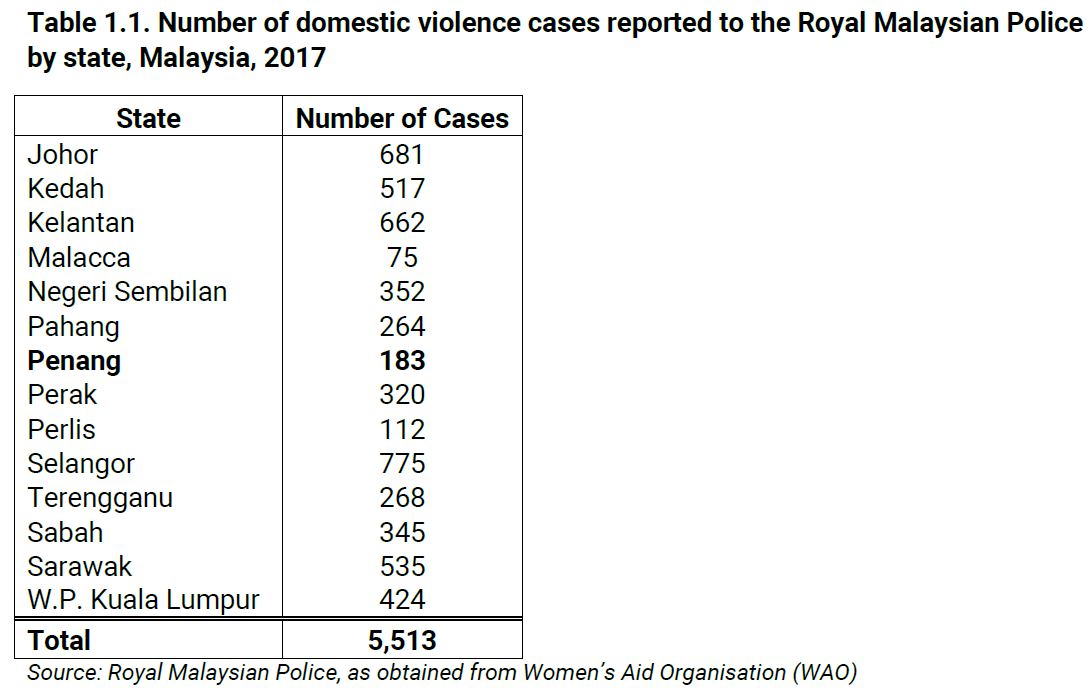

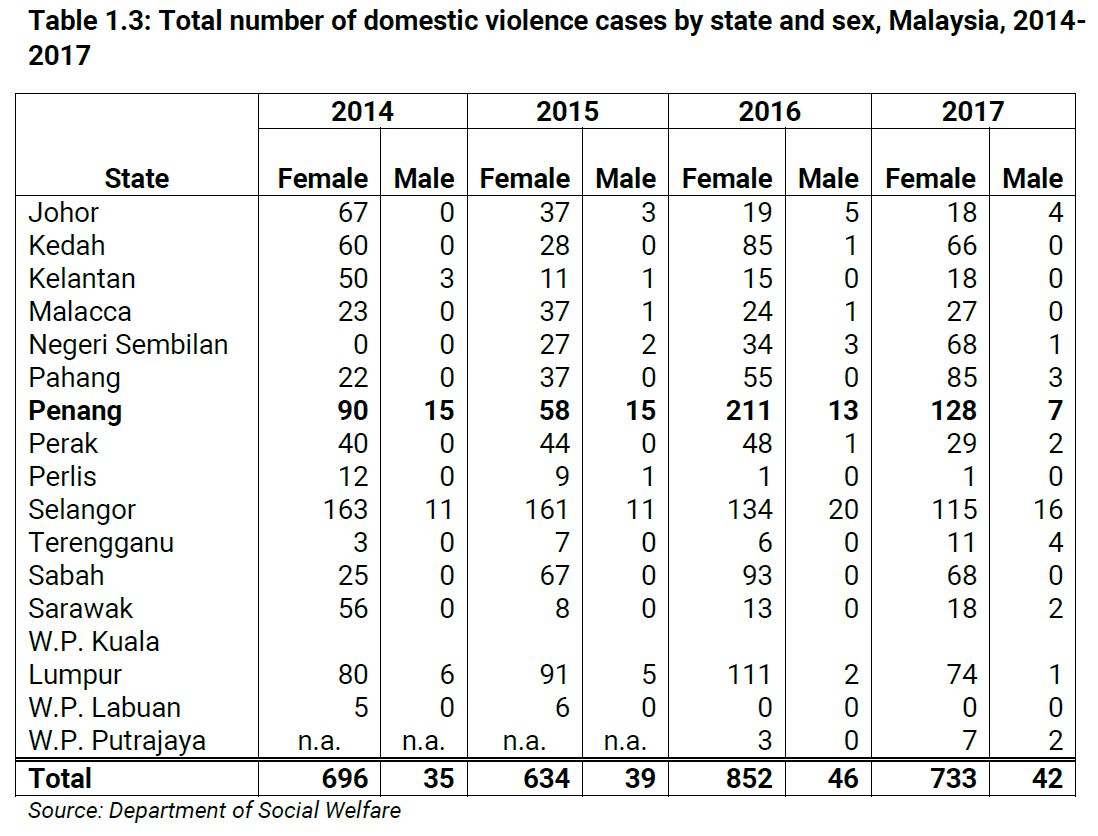

Statistics from the Royal Malaysian Police show that there were 5,421 cases of domestic violence cases in 2018, a decrease of 92 cases from the year before.[14] The number of cases referred to and managed by the Department of Social Welfare was markedly lower, at only 775 cases in 2017.[15] According to the same set of statistics, Penang recorded the highest number of cases, and was responsible for 17.4% of total cases. Selangor was close behind with 16.9% of cases. The numbers from the Royal Malaysian Police show a vastly different picture. There, Penang had 183 recorded cases, putting it among a cluster of states (Perlis and Melaka) with the lowest number of domestic violence cases. Other states showed much higher figures.[16] This incongruence in statistics suggests that in Penang, 73.8% of cases reported to the police was referred to the Department of Social Welfare. This rate is much higher than other states.

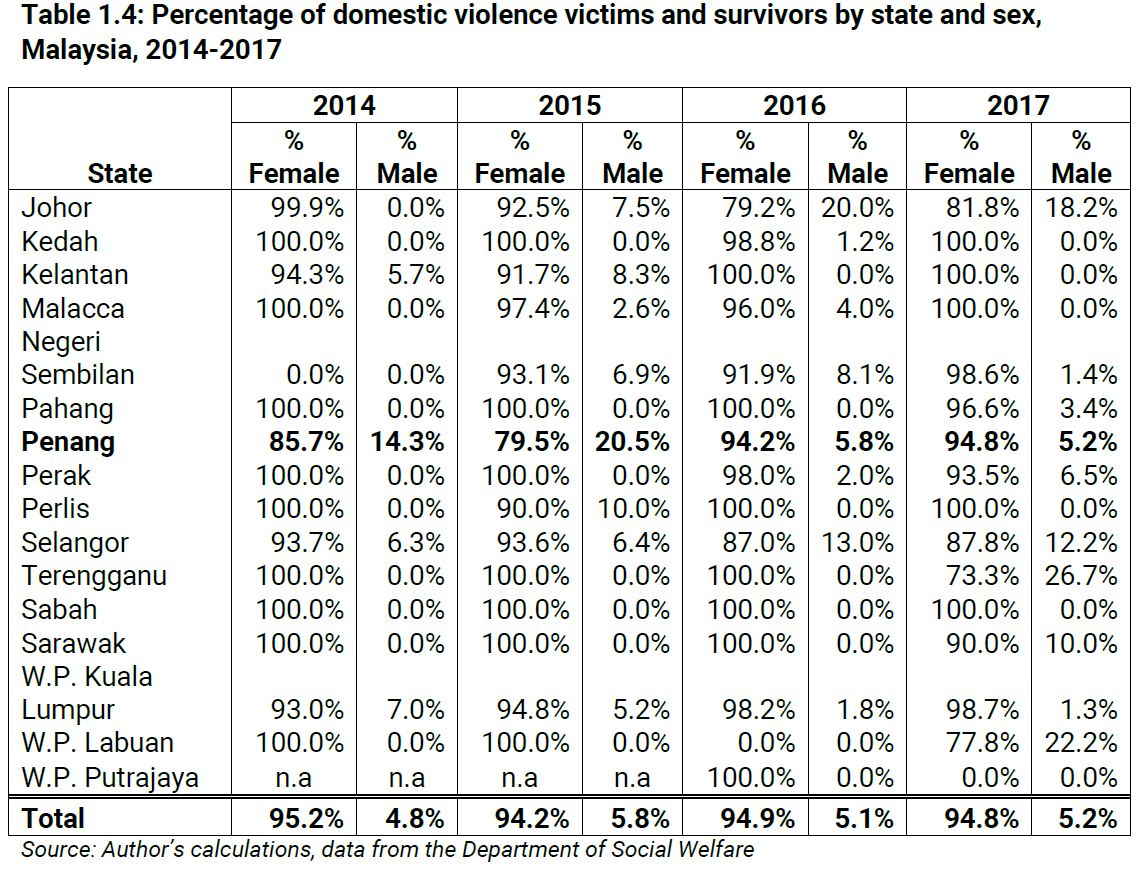

Unsurprisingly, women made up approximately 95% of all survivors in Penang. In some other states, they accounted for 100% of all survivors.[17]

Talian Kasih, a national hotline managed by the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development (MWCFD) to provide emotional support received a 57% increase in calls between 18 to 26 March. However, the Ministry claimed that the increased calls were on diverse matters relating to Covid-19, citing that there was no sign of a rise in cases of domestic abuse.[18]

In contrast, this was not the situation observed by other women’s NGOs in Malaysia. The Women’s Aid Organisation (WAO) initially saw a 14.0% increase in calls during the first two weeks of the MCO.[19] In the following first two weeks of April, however, calls had spiked by 112.2%, when compared to the same period in February. This indicates that the longer the MCO was in place, the more instances of domestic violence there have been.[20]

In Penang, YB Chong Eng, the State Executive Councilor for Women and Family Development, Gender Inclusiveness and Religions Other Than Islam, stated that during the MCO until 12 April, Penang recorded 15 cases of domestic abuse. This was according to the State Police Chief.[21] In terms of distress calls, the Women’s Centre for Change (WCC) received three calls related to domestic abuse in the first week of the MCO. This escalated to 11 calls – a 267% increase – in the second week. The second phase of the MCO recorded 19 cases of domestic violence, where four cases were urgent ones requiring immediate intervention.

WCC also works closely with One-Stop Crisis Centres (OSCCs) in Penang hospitals, and it saw the referrals for domestic violence cases increasing.

Karen Lai, the Programme Director for WCC, expressed her immediate concern that not only are the numbers of domestic violence cases increasing, the severity of the cases is also on the rise. WCC’s primary intervention is counselling, but the Centre works closely with the police and welfare department to facilitate emergency support especially in instances where there are threats of physical danger. The confinement of the survivors with their abusers during the MCO had greatly aggravated these threats.

Concurrently, Sneham Malaysia, which runs a hotline offering emotional support and counselling primarily in the Tamil language, but also in Bahasa Malaysia and English, also reported an increase in domestic abuse calls during the MCO. Dato’ Dr. Florance Sinniah, the founder and president of Sneham Malaysia, stated that the NGO had during that period received 19 calls with regards to domestic abuse, where one of the callers was a man.

Under ordinary circumstances, survivors would be able to find shelter with family or friends, or at the very least, put distance between them and their abusers. Unfortunately, the MCO had made it extremely difficult for domestic violence survivors to escape and to seek a safe place from their perpetrators. In fearing repercussions from violating the MCO, survivors remain trapped with their abusive partners, where every movement is controlled and scrutinised.

Ms. Lai pointed out that even accessing a helpline is getting increasingly difficult, as the ability to speak privately has been compromised.

The MCO has sadly enabled abusers to overtly exercise control and heighten their abuse. The pandemic is also used as a tool to instill fear and to exert control. The abusers become emboldened, knowing that their victims’ avenues for seeking help have been greatly reduced. This may have caused the severity of abuse to rise. Additionally, spending consecutive days and weeks in close proximity with their abusers will be emotionally and psychologically draining for the survivors.

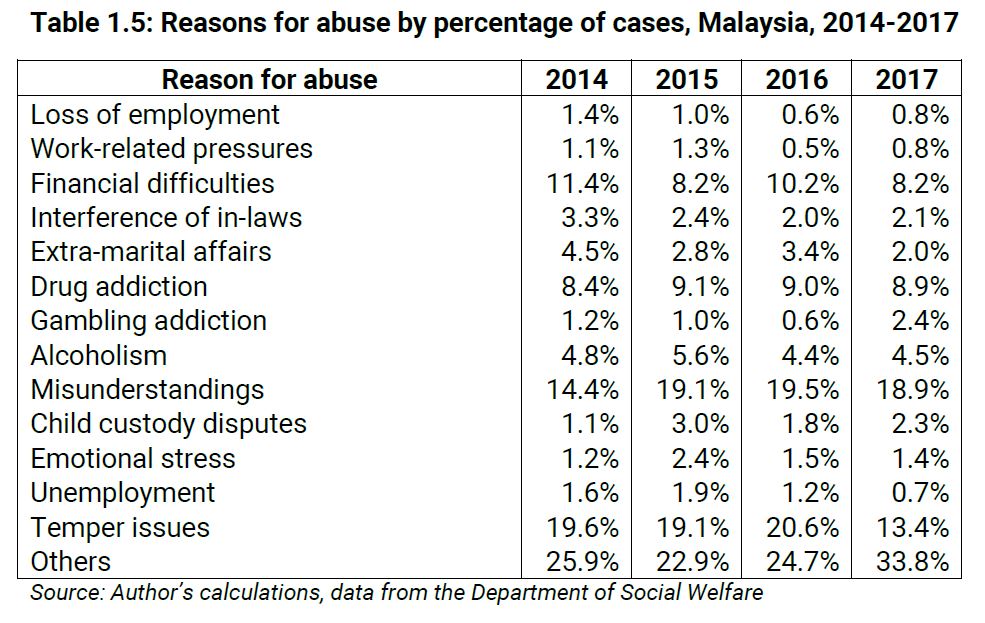

Ms. Lai further conveyed that the MCO had added financial and psychological stress which would have contributed to the increase of domestic violence. Abusers are more likely to lash out at their victims in the face of mounting financial pressures – statistics have shown that financial difficulties is one of the main factors aggravating domestic abuse in Malaysia.[22] The reduced financial capabilities of the women unfortunately also allows their abusers to further exert their power in this period.

Dato’ Dr. Sinniah expressed a similar opinion, stating that the MCO had resulted in significant financial hits in the form of the loss of employment, salaries as well as the potential loss of business. This will lead on to rising tensions and tempers, creating a situation in homes heightening the likelihood of abuse.[23] With the minimising of external social contact comes the inability of the survivors to separate themselves from their abusers, thus worsening the tensions and adding on to the abuse.

Furthermore, the victim-blaming and self-blaming mentality among survivors is a very real phenomenon – and very dangerous, even more so in this period of social isolation. Dato Dr. Sinniah revealed that in a hostile, intimidating household where stringent control had resulted in their rights being overridden, some of the callers had resigned themselves and submitted even more to their abusers. They blame themselves for not being good partners or spouses, and are hence deserving of abuse.

This situation was unfortunately made worse by the Ministry of Women’s much criticised campaigns and videos perpetuating patriarchal stereotypes where harmony in the family is solely the women’s responsibility, and propagating that they should always be in the position to forgive. Ms. Ong Bee Leng, the Chief Executive Officer of Penang Women’s Development Corporation (PWDC), cautioned against this line of thought. She stated that survivors must understand that they do not have to put up with the abuse, and that the abuse they suffer is due to no fault of their own. Survivors need support even to get help and thus, it is important for them to know that there are relatives, friends, neighbours or acquaintances who can help them.

THE RESPONSE SO FAR

In the time of the MCO, it is extremely important to ensure that help is available and extended towards domestic violence survivors. Unfortunately, the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development (KPWKM) had not taken charge in the way they should. Instead, they chose to launch a failed campaign urging women to be docile and submissive towards their husbands, using cartoons – where the character is ironically male – as an example. The Deputy Minister, on the other hand, insinuates that women should “accept, remain patient and forgive” their spouses in circumstances of conflict, even if they are abusive. The ministry had also downplayed the 57% increase of calls through Talian Kasih, saying that domestic abuse calls have not increased. In fact, there was a period in the early days of the MCO when Talian Kasih was shut down, and only reinstated after backlash.

Federally, WAO is currently working together with Mercy Malaysia and the Ministry of Health, where a national Covid-19 psychosocial support hotline had been in operation since April 15th. An additional 19 psychosocial volunteers from Mercy Malaysia and 10 counsellors from the Ministry of Health are supporting the hotline alongside 14 crisis support officers from WAO. Additionally, the publicising of Talian Kasih by Senior Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob and the National Security Council (NSC) had seen more survivors reaching out for help.

In Penang, WCC extended their hours of service from Monday to Saturday, 9am to 9pm. Social workers from WCC are working tirelessly to assist survivors, particularly for those who need urgent intervention and immediate shelter. Sneham Malaysia’s operations are now 24 hours, offering round-the-clock service. The Penang State Government, through state executive councilor YB Chong Eng, had announced an allocation of RM100,000 for the efforts to curb domestic violence and support the survivors. The funds will be distributed to NGOs working on prevention of domestic violence, and for raising awareness, in addition to increasing the availability of support services.

RECOMMENDATIONS IN THE TIME OF MCO

Until and when a vaccine for Covid-19 is found, it is highly possible that Malaysia will go through recurring MCO cycles in the next few months. Therefore, it is recommended that several crucial measures be put into place to ensure that domestic abuse survivors will be well-protected.

1. Recognising domestic violence support as an essential service

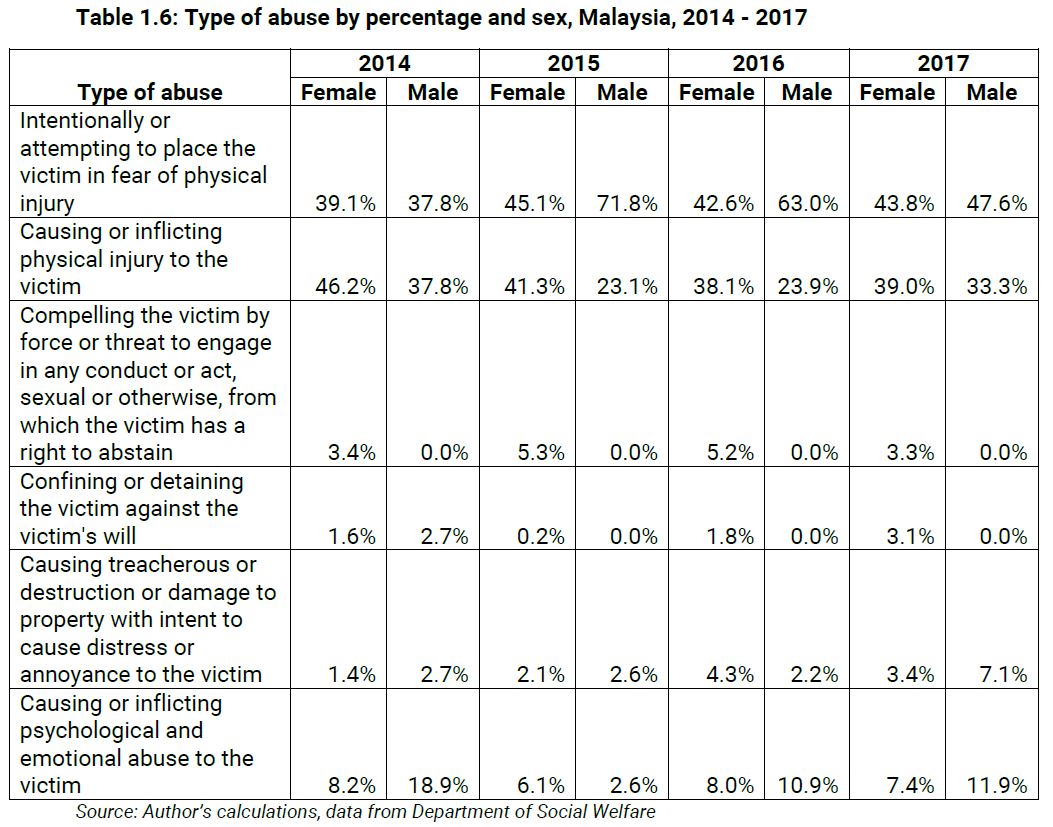

This is a measure that is currently championed by WCC and other women’s NGOs in Malaysia, and is supported by the Penang State Government. National statistics clearly portray that physical intimidation and physical abuse are two of the main forms of abuse suffered by survivors.[24] These two forms of abuse made up to 82.8% of abuse of women in 2017. Additionally, 7.6% of survivors suffered from psychological and emotional abuse.

In some circumstances, urgent action is needed to physically separate the survivors from their perpetrators. Therefore, KPWKM must work together with the National Security Council (NSC) to formulate proper standard operating procedures (SOPs) in relation to domestic violence support, where the response to domestic violence is streamlined and understood by all parties. Among others, survivors must be given access to transportation, and clearance to travel beyond the stipulated 10km radius in seeking shelter and support. The SOPs must clearly state that survivors seeking to escape their abusers will not be detained. Guidelines on the obtainment of Protection Orders during the MCO (Emergency and Interim Protection Orders included) must be clearly outlined. The SOPS should also state that government officers from the Department of Social Welfare and other relevant departments must be given clearance in carrying out their work of supporting domestic violence survivors.

2. Establishing emergency shelters

Existing women’s shelters are struggling to house survivors, given the need for social distancing and sanitisation in the duration of the MCO. While recognising that these measures are essential, it also presents the reality that there are not enough shelters available for those who need it. As such, there is an immediate need for emergency shelters.

The feasibility of state government or council-owned buildings to be converted into temporary shelters can be considered. In France, the government has partnered with hotels to provide emergency accommodation for domestic abuse survivors.[25] The viability of a similar partnership between hotels and the government should be explored. The government should ensure that there are adequate safe spaces for victims of domestic violence.

3. Increasing publicity and awareness

It is crucial that domestic abuse survivors know that they are able to seek help and emotional support during this period. In addition to providing information and advice, helplines are also a source of emotional support. In a time of social isolation, the helplines are one of the key providers for such support.

The contacts and support services and pathways from the government and relevant NGOs such as WCC and Sneham Malaysia needs to be publicised widely, most particularly in rural areas where information is harder to access.

4. Allocating financial aid to survivors

As it stands, a significant percentage of domestic abuse survivors are financially dependent on or financially controlled by their abusers. In leaving their abusive partners, the survivors may be expected to encounter difficulties in maintaining a living, even more so if they are unemployed, or had had their employment and/or income stream disrupted by the MCO.

Therefore, financial aid should be allocated to the survivors, as this will bring them economic relief as they navigate the next steps in their life. The financial aid should be easily accessible to the survivors, with minimal red tape and constraints.

POST-MCO MEASURES TO FIGHT DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

The pandemic has made surviving domestic violence more difficult, as economic downturns are expected alongside the loss of employment, businesses and income. In this sense, longer-term measures should be considered.

1. Public-private partnerships in establishing safe spaces for survivors

The example of the French government’s partnership with hotels in the period of the lockdown to provide shelter for survivors of domestic violence may prove to be a feasible plan even post-MCO. This should not be limited to major hotels, but smaller accommodation providers such as budget hotels and hostels can also play a part.

A partnership can be facilitated between the State Government, women’s NGOs and accommodation providers where a small amount of rooms can be made available for survivors, with the fee partially subsidised by the government. If there are enough players on board for this suggestion, a bevy of safe spaces can be created for the victims and survivors.

2. Increasing publicity and awareness campaigns

Awareness campaigns against domestic violence and the promotion of helplines and support services need to be continued post-MCO, and the publicity should be intensified to ensure that this information reaches all communities, and in various languages.

In Penang, PWDC organises an annual state-level campaign, Penang Goes Orange, to create more awareness for the elimination of violence against women. This involves community outreach programmes as well as awareness about available helplines. Such campaigns play an important role in the dissemination of information.

At the same time, awareness needs to be directed towards the abusers as well, in to make them recognise the harm that they are causing to their spouses. An example of such a campaign would be the one successfully conducted by the University of Melbourne, where the university developed an online tool, Better Man, centering on healthy relationships. The tool encourages men to recognise their behaviour as potentially abusive, and provides information and resources to help them curb their abusive tendencies. Making abusers take responsibility for their actions is a big step forward.

3. Establishing support groups for survivors

Domestic abuse in many ways are still considered a taboo topic in Malaysia. Survivors are often not willing to speak up, as the patriarchal constructs of society shifts the responsibility for the abuse to the abused, with the reason being that they are not “good enough” as partners. It is vital that a supportive environment be constructed for the survivors to share their experiences and their journey, and to know that they are not alone. In hearing the survivors speak about their experiences, others who suffer domestic abuse may be encouraged to seek the help they need.

4. Skills training and employment assistance for survivors

For survivors who were homemakers or unemployed, and are unskilled or low-skilled, skills training will be an extremely valuable avenue of assistance, and this will contribute towards their ability to become financially self-sufficient. After all, the gain of economic independence could mean the difference between staying put and leaving an abusive relationship.

The skills training programmes can cover technical skills such as administrative and clerical skills, or vocational skills such as crafting. For those who are abled, more highly skilled training can be provided, including programming, digital marketing and e-commerce. This will equip the survivors with the capability to generate income for themselves.

In tandem with skills training, employment assistance such as job placements and the teaching of interview skills are also vital as support mechanisms for survivors. Some survivors may have left the workforce, and some might not even have been formally working to begin with, and these survivors will need guidance on (re)integrating themselves into the workforce.

In conclusion, the Covid-19 pandemic had certainly shifted the world’s axis. For most people, staying at home is the safest measure that one could take. However, for the sufferers of domestic abuse, the safest place to be has also become the most dangerous place to be. It is essential that they are not forgotten, and their needs not ignored in this time of uncertainty.

Help and assistance need to be provided them in a timely manner. Any delay may prove fatal.

If you are experiencing domestic violence and/or need help and emotional support, please contact:

Talian Kasih (24 hours)

15999

Whatsapp: 019-2615999

Women’s Centre for Change (WCC) (Monday to Saturday, 9am – 9pm)

011 301 84001 or 016 418 0342 or 016 428 7265 or 016 439 0698

Whatsapp: 016 448 0342

Sneham Malaysia (24 hours in the duration of the MCO)

1800 22 5757

Befrienders Penang (Monday to Friday, 3pm – 12am, Saturday & Sunday, 3pm – 11pm)

04-281 5161 or 04-281 1108

APPENDIX

[1]Global Health 50/50 is an independent organisation advocating for accountability and gender equality in global health issues. The organisation is housed at the UCL Centre for Gender and Global Health.

[2]Global Health 50/50. (2020). COVID-19 sex-disaggregated data tracker, retrieved from https://globalhealth5050.org/covid19/#1586352650173-d9a8b64b-670a. The data for Spain is as of 7th April, 2020.

[3]Ball, P. (7th April, 2020). Coronavirus hits men harder. Here’s what scientists know about, retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/07/coronavirus-hits-men-harder-evidence-risk

[4]Kaos, J. & Chung, C. (14th April, 2020). Health Ministry: Majority of local Covid-19 deaths are men, retrieved from https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2020/04/14/health-ministry-majority-of-local-covid-19-deaths-are-men

[5]UN Women. (2020). The first 100 days of COVID-19 in Asia and the Pacific: A gender lens, retrieved from https://www2.unwomen.org/-/media/field%20office%20eseasia/docs/publications/2020/04/ap_first_100-days_covid-19-r02.pdf?la=en&vs=3400

[6]As an example, the gender pay gap for sales and service workers in 2018 was 28.5%, as according to the Salaries and Wages Report 2018, published by the Department of Statistics Malaysia.

[7]Broader definitions of domestic violence also include the abuse of children, parents and the elderly, although it more often refers to intimate partner abuse.

[8]Taub, A. (6th April, 2020). A new Covid-19 crisis: Domestic abuse rises worldwide, retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/world/coronavirus-domestic-violence.html

[9]Sandler, R. (6th April, 2020). Domestic Violence Hotline Reports Surge In Coronavirus-Related Calls As Shelter-In-Place Leads To Isolation, Abuse, retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/rachelsandler/2020/04/06/ domestic-violence-hotline-reports-surge-in-coronavirus-related-calls-as-shelter-in-place-leads-to-isolation-abuse/#3721281f793a

[10]Olle, E. (31st March, 2020). Coronavirus lockdown results in 75 per cent increase in domestic violence Google searches, retrieved from https://7news.com.au/lifestyle/health-wellbeing/coronavirus-lockdown-results-in-75-per-cent-increase-in-domestic-violence-google-searches-c-901273

[11]Vanderklippe, N. (29th March, 2020). Domestic violence reports rise in China amid COVID-19 lockdown, retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/world/article-domestic-violence-reports-rise-in-china-amid-covid-19-lockdown/

[12]Laudette, C.L., Melander, I. & Belen, C. (1st April, 2020). Calls to Spain’s gender violence helpline rise sharply during lockdown, retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-spain-domestic-vio/calls-to-spains-gender-violence-helpline-rise-sharply-during-lockdown-idUSKBN21J576

[13]Grierson, J. (15th April, 2020). Domestic abuse killings ‘more than double’ amid Covid-19 lockdown, retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/apr/15/domestic-abuse-killings-more-than-double-amid-covid-19-lockdown

[14]See Appendix, Figure 1.

[15]See Appendix, Table 1.2.

[16]See Appendix, Table 1.1.

[17]See Appendix, Table 1.4.

[18]Bernama, (4th April, 2020). Women’s ministry denies rise in domestic abuse during MCO, retrieved from https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/518815

[19]Arumugam, T. (4th April, 2020). MCO-linked domestic violence rises, retrieved from https://www.nst.com.my/news/exclusive/2020/04/581233/mco-linked-domestic-violence-rises

[20]News Straits Times. (17th April, 2020). WAO working with Mercy Malaysia, MoH to support abuse survivors, retrieved from https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2020/04/585300/wao-working-mercy-malaysia-moh-support-abuse-survivors

[21]Malaysiakini. (16th April, 2020). Penang records 15 cases of domestic abuse since MCO, retrieved from https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/520859

[22]See Appendix, Table 1.4.

[23]ibid. Temper issues is one of the primary reasons for abuse in Malaysia.

[24]See Appendix, Table 1.6.

[25]Godin, M. (31st March, 2020). French Government to House Domestic Abuse Victims in Hotels as Cases Rise During Coronavirus Lockdown, retrieved from https://time.com/5812990/france-domestic-violence-hotel-coronavirus/

You might also like:

![Environmental Policy Lessons to Learn From the Covid-19 Pandemic]()

Environmental Policy Lessons to Learn From the Covid-19 Pandemic

![Reevaluating Southeast Asian Public Health Strategies in Preparation for a Second Wave of Covid-19 I...]()

Reevaluating Southeast Asian Public Health Strategies in Preparation for a Second Wave of Covid-19 I...

![Securing Food Supply and Strengthening Social Resilience in Penang during the Covid-19 Crisis]()

Securing Food Supply and Strengthening Social Resilience in Penang during the Covid-19 Crisis

![Penang's Cruise Tourism Industry: Surviving the Covid-19 Perfect Storm]()

Penang's Cruise Tourism Industry: Surviving the Covid-19 Perfect Storm

![Targeted Support Needed to Keep Penang's SMEs Afloat]()

Targeted Support Needed to Keep Penang's SMEs Afloat