EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The tourism sector is currently experiencing extreme declines in revenue. Near-zero and zero revenues are the norm. Mass layoffs are imminent should this situation persist.

- Some forms of safety net exist for full-time workers (voluntary pay cuts and unpaid/ half-paid leave arrangements) in the industry, but casual and part-time workers are left unprotected.

- It is important to recognise that whatever measures are taken to protect the tourism sector, if social distancing persists and recurs, sector-wide revenue decline will continue. Hence, the key question to ask is, what will long-term solutions be for the tourism sector?

- Our key recommendations address pressing needs for the short term, but focus on the long term:

- Provide financial aid targeting SMEs

- Have frequent communication and clear information

- Assist businesses by supporting their own individually considered measures.

- Raise hygiene standards and inform travelers when Penang is safe to visit

- Identify and engage all stakeholders

- Strike a balance between economic concerns and liveability

- Increase resilience through a localisation of the sector

INTRODUCTION

The travel and tourism industry has served for decades as an important source of income for Malaysia. In 2019, the tourism sector contributed 11.5% of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) amounting to RM 173.3 billion, and provided 14.7% of total employment (2.2 million jobs) and 9.4% of total exports (RM 93.1 billion)[1].

However, the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent Movement Control Orders (MCO) have hit the national economy severely in recent months. This bodes ill for the future since no vaccine is expected to be available for many months yet. According to Prime Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin in his speech made on March 13, a loss of RM3.37 billion was experienced within the first two months of 2020; as a result, Malaysia’s GDP growth is expected to shrink by 0.8 to 1.2 points, with a potential loss of up to RM17.3 billion[2] looming.

Immediate measures to protect not only the lives of citizens but their livelihood as well, had to be taken. The Prihatin Economic Stimulus Package, a federal initiative, provided a discount on electricity bills and a postponement of tax instalment payments to affected businesses in the tourism sector for up to 6 months. Concurrently, the Penang State Government released a Relief Package to provide monetary subsidy for those affected. The additional Prihatin SME Economic Stimulus Package (PRIHATIN SME+) and Penang Business Continuity Zero Interest Loan also provided much-needed financial support and cash flow assistance to the tourism industry, where small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) account for the majority.

To boost productivity, the federal government undertook the Productivity Nexus for Tourism (TPN). The initiatives undertaken can be found at WayUp.my. These emphasise the need for a holistic ecosystem to increase technology adoption and strengthen key industry enablers[3].

Thus, the government has responded to the appeals of the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) to provide financial and political support for recovery measures targeting the tourism sector. But while the current plans aim to help the industry overcome its current difficulties, contingency measures and more concrete preparations should conditions not return to the previous normal have as yet not been discussed.

According to the Prime Minister’s message on Labour Day[4], some industries are gradually opening up but social distancing rules will continue for some time. This means that the tourism industry will not be able to recover for some time yet; and the situation for its players will get increasingly worse, and quickly.

Subsidies and financial handouts alleviate their immediate problems to some extent, but for the whole industry to survive this difficult period and have enough capacity to rebuild itself, key questions on long-term recovery need to be asked, and as early as possible. Passively hoping that visitors will return in time will not prepare the industry to take maximum advantage of or to adapt to the imminent deep changes.

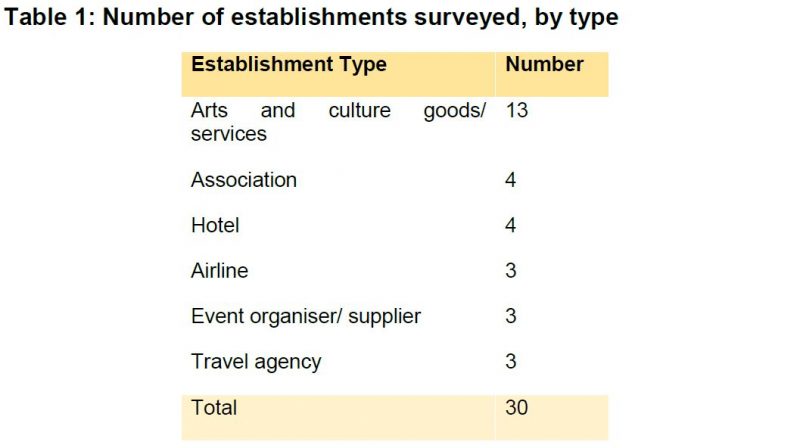

To begin the process of identifying such key questions, Penang Institute has conducted interviews with establishments based in Penang. Our total sample size was n = 30, covering key actors within the tourism sector such as airlines, hotels, travel agencies, event organisers, and arts and culture goods/ service (Table 1). Note that “Arts and culture goods/services” refer to art galleries, museums, specialist bookstores, handicraft shops and cultural spaces that offer a combination of exhibitions, restaurants and retail shops.

The survey covered four associations that together represent about 500 establishments. These are hoteliers, budget hoteliers, tour guides and other businesses related to tourism. They provided us with valuable insight into issues or sentiments that the majority of their members harbour. Given that the associations and individual businesses showed themselves to be generally consistent in the opinions they expressed in the survey, differing only in the details, we were encouraged to use data from these associations to inform our perspective of sector-wide trends, before delving into the details using information from individual establishments.

As the survey was mostly conducted through the telephone, the majority of questions were left open-ended. The codification of responses was conducted post-survey according to keywords mentioned by the respondents.

KEY FINDINGS

Changes in revenue and factors

The tourism sector is completely dependent on physical interactions and tourist movements. Unsurprisingly then, our survey found that the decline in revenue was a sector-wide phenomenon following the commencement of the Movement Control Order (MCO) on March 18.

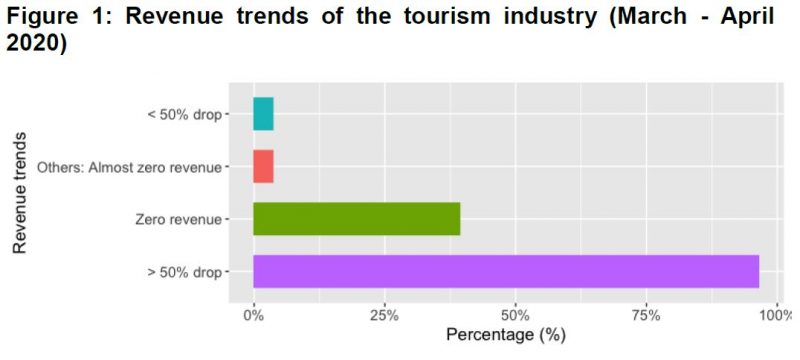

All respondents said that the Covid-19 pandemic was the worst shock to their businesses since their establishment, and all experienced revenue declines over the past four months. Our survey captured quantitative information of revenue changes for 28 of the 30 respondents, presented in Figure 1.

Almost all (96.4%) of them experienced declines in revenue larger than 50% in the months of March and April, and 39.3% of them further disclosed that they were earning zero revenues[5]. Only one respondent (an individual business owner) recorded a drop smaller than 50% in revenue.

The ‘Almost zero revenue’ response came from the Malaysian Association of Hotels (MAH). All hotels were experiencing declines larger than 50%, and zero revenue was the norm for budget hotels and tourist attractions. This trend was pervasive across all of Penang, and for many, were largely caused by the travel restrictions.

Between January and 20 March 2020, there were 18,476 hotel room cancellations in Penang alone, costing RM 8.96 million[6]. One hotel group in George Town which caters to backpackers and leisure travelers, noted that “average occupancy rates were around 60% in January and February, but fell to 23% in March and subsequently 0% in April.”

According to the Association of Tourist Attractions Penang (ATAP), among tourist sites, only those with food and beverage outlets that allowed take-away registered positive revenue. All other tourist attractions had zero revenue.

However, the removal of domestic travel restrictions is not likely to automatically translate to a rise in revenue. Tourist attractions, for example, face huge uncertainties right after the MCO is lifted. In the short term, people are likely to self-impose social distancing measures and avoid travelling even after travel restrictions are lifted. Moreover, even if tourist numbers are able to rebound quickly, tourist sites worry about new outbreaks should they be too hasty in recommencing operations.

Cash flow and staff retention issues were the immediate major consequences of the drastic drop in revenue. According to the associations, many businesses were faced with the trade-off of laying off staff to preserve cash flow in order to ensure business survival, or paying out salaries to retain staff for the future so that operations can easily recommence. Government aid was not enough to keep businesses from closing, and points to business shutdowns and job losses[7] in the near future.

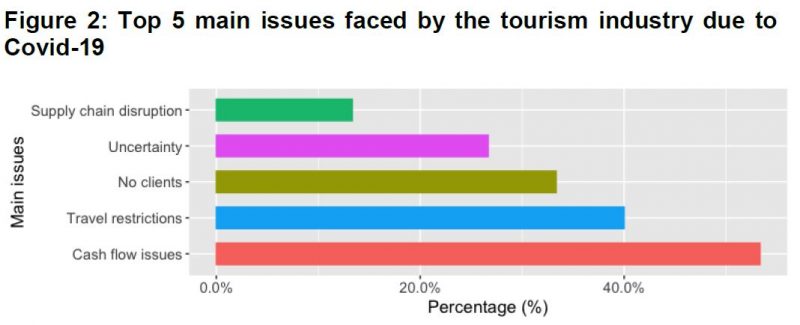

Cash flow issues were cited by 53.3% of respondents, caused by a combination of near-zero revenues and high fixed overhead costs, plus payroll costs for full time staff (Figure 2). Travel restrictions and a lack of clients (which may or may not be inherently due to travel restrictions) contributed significantly to this problem.

Those whose clients are primarily corporate travelers were slightly more optimistic about recovery once their operations recommence after the MCO, compared to those who rely on leisure travelers.

One budget hotel in Seberang Prai continued to receive enquiries from corporate travellers, but was unable to take in short-stay guests due to the MCO. At the time of survey, it remained open only for existing long-staying guests. The same sentiments were echoed by a 4-star hotel in George Town which caters to business travelers.

For 26.7% of respondents, uncertainty in the current environment was the main issue. One conference/event organizer explained that being unable to assure exhibitors that planned exhibitions would not be postponed, had impacted their revenue stream. “People are unwilling to pay for events, [so] conferences, weddings and festivals are cancelled”, said one event supplier.

In addition, 13.3% of respondents stated that supply chain disruption was an issue for them. The problem was not only faced by those who trade in tangible goods, but also those who require equipment and raw materials to provide services.

Mitigating strategies

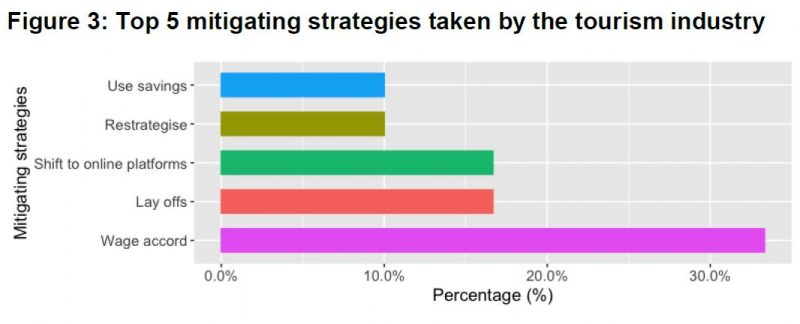

Overall, businesses were implementing austerity measures such as wage accords and layoffs. The majority had also made applications for government subsidies.

Wage accords, mutual agreements between employers and their employees to take pay cuts or unpaid/half paid leave, were mentioned by all four associations.

The Malaysian Budget Hotel Association – Penang Chapter (MyBHA) commented that “the [hotel] owners had to discuss with their workers so that they took unpaid leave or half paid leave during the MCO. Some hotels have laid off their workers to minimise their costs. But [so far], we haven’t heard of any budget hotels in Penang going bankrupt. Government subsidies did help, and workers’ salaries are being subsidised”.

When looking at individual business establishments, we found that most of the strategies taken by them targeted solving cash flow issues (9 out of 19 strategies named – not shown). The top five mitigating strategies are shown in Figure 3 below.

As a way of mitigating the problems brought up in the previous section, 33.3% of businesses surveyed established wage accords with their employees. Casual and part time workers were mostly not included in the wage accords and were unpaid, a trend seen across almost all sectors.

Since a significant number of the respondents are micro businesses with less than 5 full-time staff[8], at the time of the survey, most had not laid off staff yet and expressed unwillingness to. However, 23.3% said that they would be forced to do so if circumstances did not improve within a month or two[9].

Ten percent of respondents dealt with the cash flow crisis by using their own savings.

Roughly 17% of respondents were in the midst of moving to online platforms or were planning to. Not surprisingly these tended to be retail stores with tangible goods to sell, and tourist attractions that already had existing souvenir stores.

Re-strategising was being carried on in a coordinated fashion within each association, and by individual businesses as well. One-tenth of the establishments said that they were using the MCO period to rethink and build business resilience for future crises. One gallery owner said, “We are using this downtime to plan and strategize – how to enhance our product and services line up, [and make the business] ‘downturn-proof.’”

Return to normalcy?

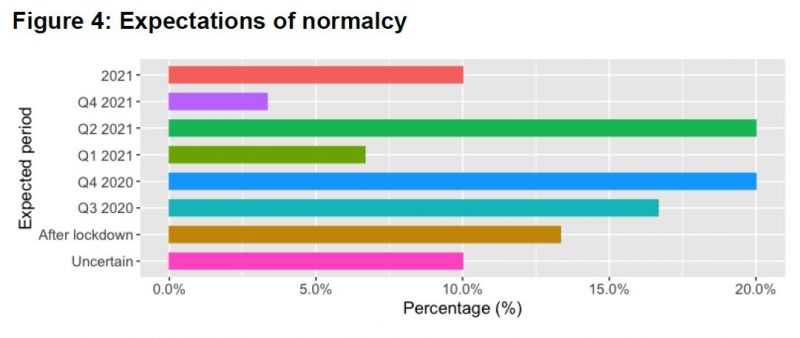

Our survey attempted to capture business expectations of economic improvements as a way of gauging business optimism or pessimism. There was almost widespread pessimism for the short term (Q2 2020), but businesses were expecting improvements in the medium and long term (Q3 2020 onwards). Broadly speaking, the sector expects business to return to normal in September 2020 at the earliest, and the latest next year.

ATAP expects tourist attractions to see normalcy return closer to the end of that range, in Q2 2021. The association was making preparations based on the assumption that the sector would be hugely impacted throughout the rest of 2020.

As shown in Figure 4, the majority of establishments expect business to return to normal from Q3 2020 onwards (77%). Ten percent of the respondents expect it to return to normal in 2021, but are unsure of the exact quarter. Only three respondents (10%) were uncertain when business would return to normal, partly because they did not know if their businesses would survive the downturn.

Few are optimistic about business rebounding right after domestic travel restrictions are lifted (13%). Most expect poorer spending power and foreign border controls to slow the recovery of business activity. One art gallery owner and retailer of fine art commented that even after the MCO was lifted, business would remain slow for him because existing customers had said that they would be “more conscious of spending money” after it.

Like many surveyed establishments, the Teochew Puppet and Opera House, for example, expected domestic travel to pick up before international travel. “For foreign tourists, I expect [business] will return to normal only at the end of the year or even next year. But regarding the workshops and performances for our local audience, I think it will be in the second half of the year, after June or July.”

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS

During the fight against Covid-19, it is good that cogs are put in place to ensure that a movement restriction order does not hinder the generation of income for our citizens completely. That said, should the opportunity for an industrial transformation arises, it should be embraced and studied with an open mind.

It is crucial that the government grasps the development trend of the tourism sector and takes timely measures to protect the livelihoods of those in it, by making use of public-private partnerships, providing guidance, and intervening where there are clear market failures. We detail these in the key recommendations below, separated into short- and medium to long-term initiatives.

Short-term initiatives

1. Provide financial aid targeting SMEs

SMEs account for the majority of businesses in the tourism sector, and one of the top issues that they face is cash flow. The federal and State Government have attempted to alleviate this problem through several relief packages, as mentioned in this report. However, for the majority of businesses, these measures are insufficient to keep them afloat for anything longer than a month or two, especially in sectors where there is no way business can resume immediately after MCO, such as event organizers.

Any future subsidies, tax reliefs or grants must be targeted, bearing price elasticity[10] in mind. To ensure that gains go primarily to businesses, subsidies should be given directly to businesses that sell goods or services whose demand is price elastic. These are goods/services where the quantity demanded is very sensitive to price changes. In the case where supply cannot change immediately, such as hotel capacity, subsidies can be channeled to consumers.

Furthermore, policymakers must always consider the impact that financial assistance will have (or not have) on SMEs. For example, application processes for assistance can be made as affordable and simple as possible for these companies that may not have the administrative know-how, financial resources, or time for what to them are complex matters.

2. Have frequent communication and clear information

Uncertainty is one of the main issues faced by the tourism sector according to the survey, because it delays business decisions.

Bearing in mind that businesses need to convey plans to their own clients/suppliers, and make business continuity plans, there must be frequent and clear information from the State Government.

A concrete and cohesive action plan within the context of this pandemic should be communicated quickly and clearly to help businesses act confidently.

Frequent but unclear information from the State will do more harm than good, and the State should ensure that any policies or action plans announced should be available in writing, accessible online by the public to avoid confusion.

3. Assist businesses by supporting their own individually considered measures

Being most attuned to their own needs, businesses will have already identified necessary solutions that they can individually take to safeguard themselves. As they are likely to have begun the groundwork already or are looking for ways to facilitate their efforts, any assistance provided in those areas is likely to be more effective.

Policymakers may consider two aspects in this matter. What solutions are businesses trying to implement individually? And which of these can be aided by the degree of centralisation that can only come from the state?

Our survey indicates a few areas where help can be provided. Due to social distancing measures, many are attempting to move onto online platforms (though these are largely retailers of tangible goods), and businesses are increasing their rate of technology adoption, with which some require guidance. The state may direct businesses to existing e-commerce platforms, provide purpose-built platforms[11], or deliver guidance on digitising certain core processes, or upskill their employees[12].

Also, the Malaysian Association of Hotels (MAH) and the Association of Tourist Attractions Penang (ATAP) indicated that they are in the midst of designing health and safety procedures to be adopted by their members. The state can aid these efforts by reviewing and accrediting the procedures, to boost visitors’ confidence.

Several hotels are experimenting with various strategies, such as providing takeaway services, to maintain some form of income. The state may use this as an impetus to encourage the switch towards more eco-friendly and sustainable practices, in line with the “green hotel initiative” suggested in Penang2030. One example is to promote the switch to pre-packed breakfasts delivered to guests’ hotel rooms, in lieu of buffets, to address food hygiene concerns or congregating in an enclosed cafe/ restaurant space. It aids planning and reduces food wastage common at buffets. Buffets can be phased in gradually, alongside the pre-packed breakfast option. Another idea is to provide hygiene-conscious guests with branded reusable and recyclable bottles or lunch boxes and cutlery to use as they travel.

Many innovative ideas can be developed through continuous discussion. Frequent dialogue with businesses needs to take place to identify their pain points, how they are already dealing with them, and what gaps can be filled by the state.

Medium to long-term initiatives

1. Raise hygiene standards and inform travellers when Penang is safe to visit

Tourists may avoid travelling even after the pandemic has died down due to doubts about health safety at travel destinations. It is therefore imperative that efforts are stepped up to increase hygiene standards in public areas, and to reassure visitors of the overall consciousness of hygiene with regards to contagions and otherwise.

Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) should cover the entire travel experience, from the point of arrival to the point of departure. Once implemented, SOPs should be strictly regulated, especially in public places where the free-rider problem is especially prevalent. Where cooperation among stakeholders (users/beneficiaries of the public spaces) is unlikely, the State Government should be directly responsible for maintaining the cleanliness of the space.

Activities can be adapted to adhere to social distancing measures. For example, the state can begin encouraging niche, small group events instead of mass gatherings (see point 3) to avoid crowds congregating. Tourists should be briefed on social distancing measures at entrances, and their numbers can be limited by using a reservation/ticketing system (paid or free). All this will show the State Government’s commitment to traveller safety, and encourage tourist sites to be more aware of visitor wellbeing and to invest in quality of experience rather than visitor numbers.

Once ready to receive visitors, the State should launch a tourism campaign to inform travellers that Penang is safe to visit, and why.

2. Identify and engage all stakeholders

Building and managing a more resilient tourism sector will require the State Government to first identify all stakeholders, and engage them through frequent dialogue, in order to form a comprehensive understanding of their contributions, needs and perspectives.

As an example, groups such as artists and other providers of arts and culture services, provide a wide range of services to support the tourism sector, but have had their needs and importance overlooked due to their nature regarded as an unstable industry. In other cases, the self-employed or smaller establishments are left out of discussions, because larger suppliers are more visible and are usually the ones to have established working relationships with the state through previous projects.

Efforts such as engaging the arts and culture community through the Penang Art District[13] during this pandemic are commendable, and should continue in the long term as a way of creating more dialogue amongst all stakeholders and giving previously sidelined groups a voice in the discussions.

Furthermore, the State needs to engage business owners to know when they are ready to restart operations and what type of promotions or travel incentives are feasible, in order to form a consistent and cohesive tourism campaign message that works for all.

3. Strike a balance between economic interests and liveability

Before the outbreak, Malaysia’s tourism strategy focused on the country’s cultural vibrancy. Among other things, Malaysia’s arts and cultural festivals were a major pull for tourists[14]. Penang State’s tourism campaign, “Experience Penang 2020: The Diversity of Asia”, started before the Covid-19 pandemic, also exhorts similar characteristics, marketing the state’s vibrant festivals such as Thaipusam, Songkran, Penang Bon Odori and Chingay Parade, as well as its authentic street food[15].

The campaign followed a Malaysian tradition in marketing tourism. Its success, however, has been the very same reason. It’s the long-term unintended consequences that have hardly ever been examined. This model inadvertently encourages mass groupings – contributing to social and ethical issues such as the commodification of culture, traffic congestion, environmental degradation and vulgar gentrification.

Though these problems have been around for a long time, they are often ignored by city planners. This is largely because tourism is perceived merely as an economic undertaking, fleeting and temporary in essence. Case in point: cruise tourism is encouraged because it garners huge numbers of tourists and creates business opportunities, yet, its obvious detrimental impact on the environment and industrial structures are rarely discussed[16]. In addition, vibrant one-off street festivals are often held without consideration for traffic congestion, pollution and discomfort experienced by residents in surrounding areas caused by the sudden increase in tourist numbers.

To improve the resilience of the tourism industry, there is therefore a need to strike a balance between immediate economic interests and liveability, while avoiding over-dependence on particular income generators.

4. Increase resilience through localisation of the sector

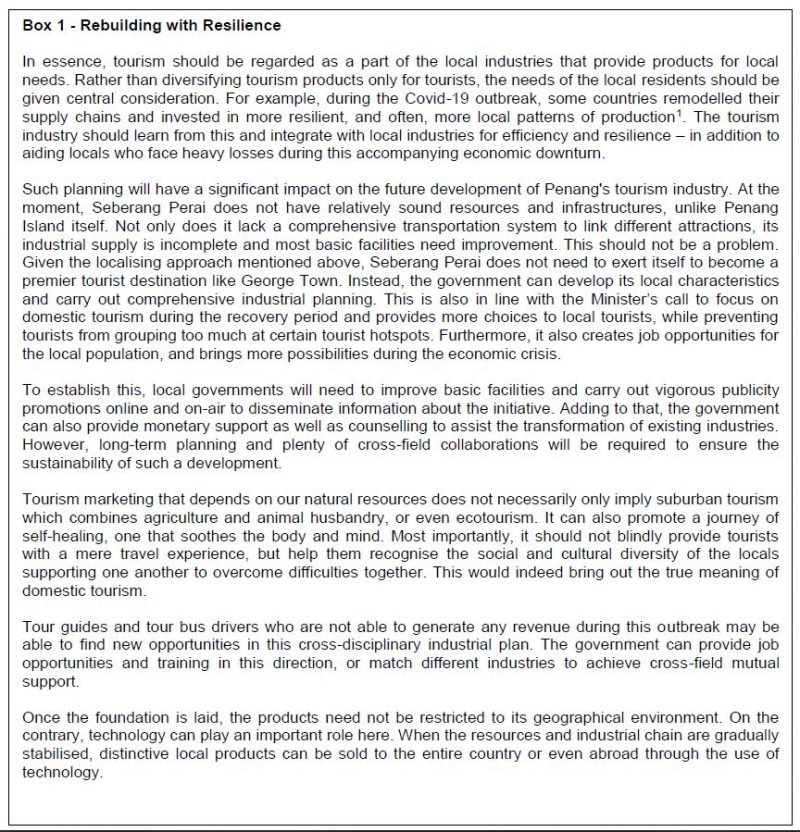

The devastation caused by Covid-19 has made it clear to all sectors that there is a need to increase resilience by remodeling supply chains and investing in more local patterns of production and consumption (refer to Box 1 for a detailed explanation and strategy of how this can be achieved).

Domestic/local tourism can be encouraged by implementing dual pricing for domestic and international tourists, and reduced off-peak prices. These measures also prevent overcrowding as a means of avoiding future outbreaks.

Furthermore, the State could re-allocate resources to suppliers who provide goods and services that suit local tastes, and target tourism campaigns at Malaysians and Penangites. An example of this is to partner with firms to provide workers in Penang with non-wage benefits in the form of travel incentives[17], or cooperate with local businesses to craft travel package discounts for local residents.

Related to that, the State Government must take the lead in a campaign to support local businesses. This is not simply an issue of ‘buying local’. For the state, this is also:

a) engaging domestic suppliers in order to understand market inefficiencies that obstruct them from meeting or creating demand,

b) addressing these inefficiencies so that businesses are able to function better, and

c) promoting dynamic competition within the sector so that innovation continually occurs.

CONCLUSION

The Covid-19 pandemic has subverted our way of life and together with it, brought great challenges to the economic structure. The tourism industry has suffered unprecedented impact, but waiting it out by remaining idle will do no good. Strengthening the resilience of the industry is the way to go, and the planning and action for this should begin before the pandemic comes to an end – if we are to come out of it well equipped.

It is important that resources and capabilities are adequate before economic recovery. Whatever the case, we should concurrently seek more dynamic and longer-term solutions. Industrial transformation is inevitable.

In addition to moving towards industry 4.0, we should also realize that laying the ground for more cross-field collaboration can keep the industry adaptive, and equip it for the new (or next) normal.

[1]“Malaysia 2020 Annual Research: Key Highlights”, World Travels and Tourism Council, 2020.

[2]“Muhyiddin: Tourism Industry Hit Hardest by Covid-19, Faces RM3.37b Loss”, Malay Mail, 13 March 2020. https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2020/03/13/muhyiddin-tourism-industry-hit-hard-by-covid-19-to-lose-rm3.37b-while-gdp-s/1846323

[3]“Tourism Productivity Nexus”. Productivity Way Up Malaysia. http://www.wayup.my/nexus/tourism

[4]“Perutusan Khas Perdana Menteri sempena Hari Pekerja 2020”. 1 May 2020. https://www.pmo.gov.my/ms/2020/05/perutusan-khas-perdana-menteri-sempena-hari-pekerja-2020-2/

[5]Revenue information was provided on a voluntary basis. The actual percentage of businesses making near zero revenue is likely to be much higher. Malay Mail, 1 April 2020. https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2020/04/01/covid-19-tourism-industry-at-a-standstill-calls-for-subsidies-incentives/1852372

New Straits Times, 1 April 2020. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2020/04/580313/zero-income-taman-negara-tour-guides-due-covid-19

[6]Malay Mail, 17 April 2020. https://www.malaymail.com/news/life/2020/04/17/covid-19-malaysias-hotels-draw-up-new-strategies-in-view-of-rm3.3b-in-losse/1857655

[7]Already, hotel closures are appearing in the news at a startling rate and forewarn of a similar fate for the rest of the industry. Malaysiakini, 27 April 2020. https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/522804

[8]Out of 18 respondents who provided staff data, 14 were micro businesses (47% of the total sample). The average number of full-time staff for this category of respondents was 2.6.

[9]Occurrences of layoffs would be more widespread if we weighted the responses of respondents by the number of businesses they represented.

[10]Price elasticity is how much quantity supplied or demanded changes when price changes. For price-inelastic goods, percentage change in quantity supplied/demanded will be smaller than percentage change in price. And the opposite for price-elastic goods. Price elasticity matters because it determines the cost of subsidy to the government, the final price, quantity demanded, and whether businesses or consumers are primary beneficiaries of the subsidy.

[11]Malay Mail, 10 April 2020. https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2020/04/10/muslims-can-pre-order-food-for-ramadan-through-penang-councils-online-food/1855361

[12]As is being done by Productivity Nexus for Tourism (TPN).

[13]“Editorial”, Penang Art District. https://penangartdistrict.com/category/blog/

[14]“About VM2020”. Malaysia Truly Asia. https://vm2020.malaysia.travel/about-vm2020

[15]“Tourism”. Penang State Exco Office for Tourism, Arts, Culture and Heritage. https://petach.gov.my/tour/

[16]“Save the Cruise Industry? Some Say Let It Sink”. The Tyee, 31st March 2020. https://thetyee.ca/News/2020/03/31/Cruise-Ships-Not-Vital-Part-Of-BC-Economy-Say-Critics/

[17]The Hungarian government for example launched a benefit programme to direct spending towards tourism services and incentivise domestic travel. World Travel and Tourism Council, 5 December 2018. https://wttc.org/en-gb/Research/Insights

You might also like:

![Planning the Economic Future of Penang beyond Covid-19]()

Planning the Economic Future of Penang beyond Covid-19

![Specifics of the Impact of Covid-19 on the Young]()

Specifics of the Impact of Covid-19 on the Young

![Covid-19 Exit Strategies in East Asia: Choosing between a Suppress and Lift Procedure and a Stagge...]()

Covid-19 Exit Strategies in East Asia: Choosing between a "Suppress and Lift" Procedure and a Stagge...

![Domestic Violence and the Safety of Women during the Covid-19 Pandemic]()

Domestic Violence and the Safety of Women during the Covid-19 Pandemic

![Covid-19: Impact on the Tertiary Education Sector in Malaysia]()

Covid-19: Impact on the Tertiary Education Sector in Malaysia