EXECUTIVE SUMMARY[1]

- Penang’s economy showed very encouraging signs at the beginning of 2020. It had secured record-large foreign direct investments in 2019, a clear sign of Penang’s upbeat global standing as a place to invest in, to live in and to work in. It also enjoyed political stability at a time when politics at the federal level was becoming rather chaotic. The rising number of tourists was also an indication of Penang’s growing reputation.

- The Penang State Government has since the general elections of 2018 been developing a paradigm called Penang2030 to manage disruptions to traditional industries wrought by the digital revolution. Investing in digital technology offers Penang a promising path towards becoming a resilient and confident society in the wake of Covid-19.

- The Covid-19 pandemic that saw the Movement Control Order put in place on 18 March has turned out to be a mega-disruption on society.

- The people empowerment and public participation in policy making which anchor Penang2030 and its expressed wish to create a family-focused green and smart state, provide fertile ground for growing a resilient post-Covid-19 society.

- The key issues that have called for most attention during the MCO are also making society cognisant of its weaknesses. The measures taken to remedy these should reasonably form the basis for long-term policy making, and even nation-building.

- A reformulation of the state’s executive council portfolio nomenclature to reflect this realisation appears necessary, and in line with the state’s vision to “empower the people”, each of these portfolios should have mechanisms to enhance the role of experts and concerned citizens in the policy-making process.

INTRODUCTION

Although the Covid-19 pandemic caught all governments by surprise, some were better able to act to contain its spread than others. The reasons for this are many – some due to good fortune, some to structural conditions and of course, some to good decisions by governments and the efficaciousness of those decisions.

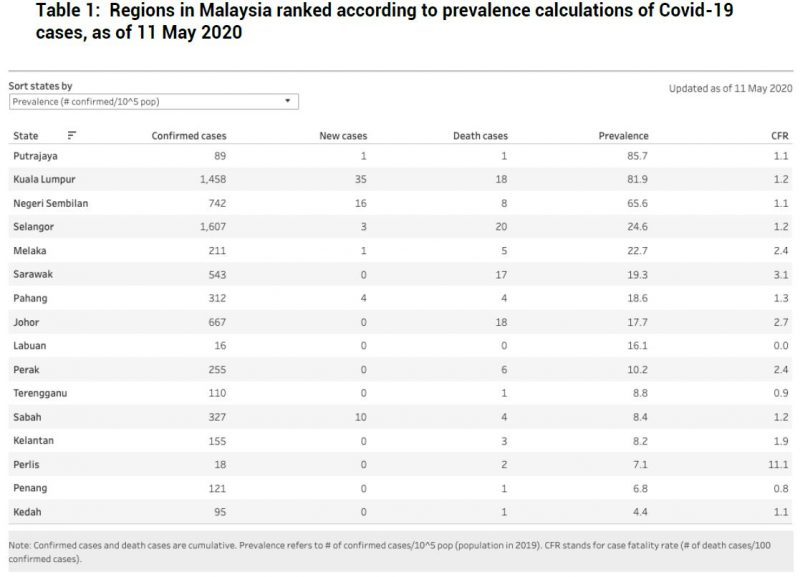

This is also true where sub-national regions are concerned. In Malaysia, how the outbreak has been working itself out over recent months has varied from state to state. The northern peninsular states (Kedah, Kelantan, Penang, Perlis and Perak), along with Sabah at the eastern end of the country, have so far been spared the worst of the pandemic within the country.

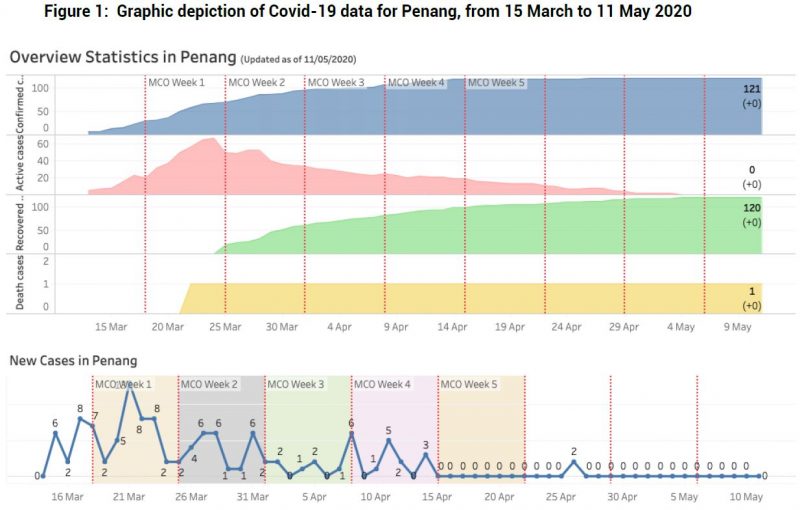

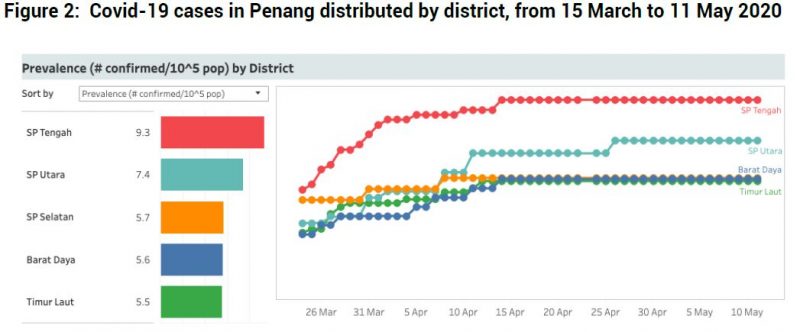

Source: https://penanginstitute.org/resources/key-penang-statistics/visualisations-of-key-indicators/covid-19-data-snapshots-for-malaysia/

This paper focuses on the specific case of Penang, but considers the conditions for its long-term management of the disease more than how it has fared during the Movement Control Order (MCO) period that began on 18 March 2020. Arguably, Penang is in a better position than most other Malaysian states to manage the severe challenges posed by the pandemic, and to move beyond them.

Source: https://penanginstitute.org/resources/key-penang-statistics/visualisations-of-key-indicators/covid-19-data-snapshots-for-malaysia/

While the island part of the state is largely urban, and entry points are limited to the airport, the ferry system and the two bridges, the mainland part of the state – Seberang Perai – is more open where traffic is concerned, and is also more semi-urban. These differences necessitated different configurations for how the state implemented MCO regulations.

In any case, competent implementation throughout the state and in neighbouring states, along with the high public compliance and understanding of the seriousness of the situation soon saw practically no new cases (excepting one case involving two persons which was quickly managed) being reported after 15 April, one month into the MCO period.

Apparently, Penang also had the good fortune of not having had infected tourists visiting just when they were most infectious, which for example was the case in the southernmost peninsular state of Johor. Malaysia’s worst Covid-19 cluster, which began from a four-day Muslim gathering held in Petaling Jaya from 27 February to 3 March, and attended by 16,000 people, did not affect Penang as badly as it has done some other Malaysian states.

When the federal government decided on Labour Day to ease the MCO by 4 May through what it calls a Conditional Movement Control Order (CMCO), Penang was one of the eight or so states that chose to lift restrictions more slowly, and in three phases instead to reach the situation allowed by the CMCO. Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin then announced on 9 May to extend the CMCO till 9 June. Apparently, with the situation still not fully under control, allowing for inter-state travel during the Ramadan fasting month and especially in light of the traditional celebrations attendant on the ending of that month, was deemed too big a risk to take.

Source: https://penanginstitute.org/resources/key-penang-statistics/visualisations-of-key-indicators/covid-19-data-snapshots-for-malaysia/

Penang having voted in a new government distinct from the federal administration in 2008, public support for – or at least broad acceptance of – the Pakatan Harapan/Pakatan Rakyat administration has remained strong. This had allowed for political stability and consistency in policy making, as well as a gradual strengthening of Penang’s reputation as a society implementing steady reform. The latter was enhanced further when the federal government also fell to the Pakatan Harapan on 9 May 2018, and the Penang State Government increased its representation to an astounding 37 of 40 state assembly seats.

Penang society being therefore more cognisant of a positive spirit of change affecting the country – or at least more convinced of it – than was the case in other parts of the country, the new Chief Minister, Chow Kon Yeow, decided already in late 2018, four months after he took office, to announce a vision he calls Penang2030.

PENANG2030 BEFORE COVID-19

Most gratifying for Penang, its socio-political stability in 2019 led to record-large foreign development investments flowing into the state. In fact, if one were to consider the RM15 billion in FDI secured for Penang together with the RM8.086 billion gained by neighbouring Kedah, whose industries function in close conjunction with Penang’s, more FDI was attracted in 2019 to the north-western corner of the peninsula, than the sum acquired by Selangor, Johor, Perak and Pahang combined.[2]

Penang2030 is in essence an attempt to excite the private sector, the public sector and the community in general into giving serious thought, and to do that in close discussion with each other, on the many disruptions that the digital revolution, often called Industry 4.0, would bring, and how Penang should prepare for it.

Appropriately aimed at achieving a “Family-focused Green and Smart State that Inspires the Nation”, Penang2030 prioritises the following mission for the state:

1. Increase Liveability through public welfare, public hygiene and environmental consciousness;

2. Upgrade the Economy through creative industries, agricultural development, environmental consciousness and comprehensive digitalisation;

3. Empower, Expose and Educate Citizens in economic, sociocultural and technological matters, and democratise policy making;

4. Improve Resilience through spatial planning, connectivity, administrative reforms, and disaster management.

Fortunately, just before the pandemic began disrupting the economy in early 2020, the State Government had managed to establish Digital Penang as its institutional arm for providing advice on the digital economy, and for planning and coordinating digitalisation initiatives. In general, the pillars for digital development in Penang are identified as: digital governance, digital infrastructure, digital community and digital economy.

In that way, Penang follows the example of many national and sub-national governments the world over in working out the best means for adapting to the digitalising world. However general these means may seem, in practice, they can best gain effective results if developed according to local socio-economic, socio-political and cultural conditions.

Although much planning for Penang’s future development had been done in recent years, the Covid-19 outbreak has necessitated a sharpening – a refining – of the key adopted ideas. The goals may remain more or less the same, but a re-prioritisation is clearly needed, and with that, an urgent rethinking on the means to achieve these goals.

Of interest to the people of Penang at this point is the story of one of its most famous sons, Wu Lien-Teh, “the plague fighter” who in 1910-11, successfully fought the pneumonic plague outbreak in Manchuria, saving millions of lives and in the process using some of the approaches that we see being used against Covid-19.[3] Penang had also lived through the 1918 influenza pandemic, and survived it better than others states in Malaya, thanks to the local community’s proactive initiatives.[4]

THE MEGA-DISRUPTION THAT IS COVID-19

The highly infectious Covid-19 could become a global pandemic so quickly largely by way of the intensely trafficked routes for human travel that had developed in recent decades. And so, the obvious initial reaction from governments was to control inflows and outflows of people at border points, and then to intensify this measure as the days went by. This did not only greatly trouble travellers, it quickly bottlenecked and even broke industrial supply chains throughout the world. The movement of raw material and finished products was badly affected.

Some panic-buying of household items was immediately evident throughout the world. But what quickly became of serious concern to governments was the issue of food security: Has the globalisation of supply chains developed to such an extent that their sudden disruption would leave people lacking access to bare essentials, such as foodstuff, once local stocks were depleted?

Food security thus became an immediate concern for local governments, more so than the supply of items that households deemed essential, such as toilet paper (!). Public hygiene also became a critical issue. Social distancing has therefore had to be strictly enforced.

These conditions amount to a cultural challenge for the people, and an evolution in the role of the state. The latter signals a return to pre-neoliberal days when the state existed to ensure certain collective functions, not as an authority whose main task is to outsource them to private sector players. These functions include the management and supply of public health, public education, public transport and infrastructure, reliable utilities, public security, et cetera.[5]

For national and sub-national governments alike, the social distancing measures they have been forced to impose have been a necessary evil where the economy is concerned. These measures may save lives, but at the same time, they potentially destroy livelihoods. This is true everywhere, varying only in the details.

Data from the Department of Statistics Malaysia show that 67.8 percent of businesses had had no revenue at all during the MCO while 30.1 percent think that they can survive beyond three months. While 19 percent of the registered national workforce had their working hours reduced, 16.5 percent had to go on unpaid leave, while 3.8 percent lost their jobs. Apparently, the arts, entertainment and recreation sub-sector suffered the most job losses most immediately.[6]

Unemployment for Malaysia as a whole went up from 3.6 percent in February 2020 to 3.9 percent a month later, coming close to the 4 percent experienced during the financial crisis in 2009. Exports shrank by 4.7 percent year-on-year in March 2020, and imports by 2.7 percent.

For an economy like Penang’s, where 99 percent of registered companies are classified as SMEs, where a sizeable proportion of the population are self-employed or are gig industry entrepreneurs, and where the services sector accounts for half the state’s GDP, the economic impact has been immediate and widespread. Tourism, be it in the form of medical tourism reliant on Indonesian patients, or MICE, or the cruise ship industry, has been severely hit[7]. As noted in Penang Institute’s ISSUES from April 2020, “Penang Economic Outlook 2020: A Rough Year Ahead”:

Looking forward, the picture is gloomier. In 2020, Penang’s GDP is expected to experience the weakest growth rate in a decade. Service activities will see the greatest slowdown due to the bearish tourism outlook, while accommodation services, restaurants, transportation services, retails and trade will be severely affected in the first half of 2020 by the Covid-19 pandemic. Growth may catch up gradually in the later part of the year, but that will depend on how the Covid-19 pandemic develops. The construction sector will slow down further in the face of the general economic recession. Buyers are expected to be extremely cautious while property developers postpone construction plans.[8]

CARING FOR THE PRESENT TO PREPARE FOR THE FUTURE

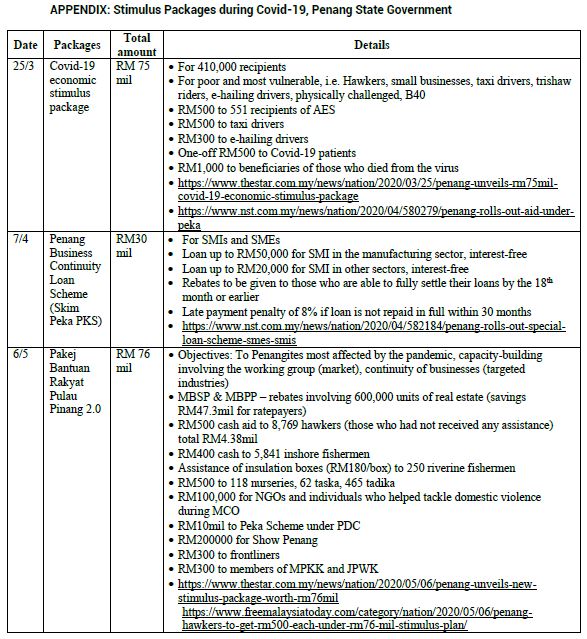

While faring commendably well where keeping the public uninfected is concerned, the harm done to livelihoods by the MCO has been severe, and this will continue for some time to come. As part of its damage control measures, the Penang State Government therefore rolled out several so-called “stimulus packages” to complement those announced by the federal government (see Appendix).

In preparing for the long struggle against Covid-19 therefore, the Penang State Government will have to determine where it can best invest its resources and its planning power. Some of Penang’s strengths have been mentioned above, and in the Chief Minister’s words, the policy targets now chosen by the government is expressed through the acronym, CARE:

1. Containing the pandemic;

2. Adapting institutions for the next normal;

3. Rescuing the people and the economy, and:

4. Empowering community.[9]

As with Penang2030, these goals attempt to be comprehensive in reach. Elsewhere, the chief minister has called this a whole-of-society approach.[10] The list of four targets combine both long-term and short-term goals; this is understandable, given the fact that the pandemic is expected to be around for some time yet.[11]

As we contemplate the post-Covid-19 future, it is strongly advised that the long-term measures be considered as extensions and institutionalisations of those undertaken to manage the challenges already clearly identified in the short term. This approach will provide conceptual focus, minimise conjectures and most importantly, optimise the comprehensiveness, comprehensibility and practicableness of long-term policies taken as a whole.

The rest of this article lays out longer-term policy options for managing the Covid-19 disruption, as suggested by this down-to-earth approach.

Containing the pandemic

Where containing the epidemic is concerned, the first dilemmas immediately faced by policy makers have been over issues of healthcare capacity capability and logistics, as well as public hygiene. This was immediately followed by worries over food security.

Even before movement control was implemented nationwide, it was already abundantly clear that state capacity to regiment public behaviour, both at the individual level and in economic activities, would be put to the test. In Penang at least, public willingness to comply with safety rules did not seem to be too much in question. And in fact, faith in public compliance with the MCO proved to be well-founded throughout the country, and definitely so in Penang. Used to taking care of themselves, and empowered in the sense of having picked a government of their own choice – evidenced in the last three elections – the people of Penang understood the situation well enough to accept the emergency rules put in place on 18 March.

The need for good channels of communication providing reliable information also became painfully clear. As luck would have it, Malaysians are digitally very well connected, and this proved a boon in the struggle against this global pandemic. The exemplary way in which East Asian societies that are highly digitalised, such as those of South Korea and Taiwan, handled the pandemic highlights further the need for Penang to turn its governance, its community and its economy into a competitively digitalised one.[12] Indeed, the MCO would have been quite intolerable at the individual level, and difficult to manage administratively, if Malaysians had not been as digitally connected as they were when the pandemic began.[13]

In line with this, the acquisition for Penang of world-class internet connectivity, and of accompanying good cybersecurity, reliable high-quality information channels and filtering mechanisms against fake news, gains new urgency.[14] The state’s new agency, Digital Penang, therefore has its work cut out for it in the coming months.

Given how supply chains broke down throughout the world in the wake of the outbreak, a localisation of global supply chains has become the wisdom being shared by economists throughout the world.

Where food is concerned, this appears all the more pressing a matter. Already in the days before the MCO came into play, food security had become a concern for the authorities as well as households.[15]

The MCO’s stoppage of economic activities affected the poor and Penang’s many micro and small enterprises even before the job security of industrial and other salaried workers became a pressing concern.[16] The issue of inequality may therefore be expected more than ever to become a critical political issue in the coming months – and years. Handing out of cash, though necessary in times of crisis, will not suffice. Governments are themselves, after all, facing depressed economic times ahead.[17] The providing of relevant education and economic opportunities will be a critical task for governments in the “new normal”. To manage that, digitalisation of education to a competitive level will be necessary.[18]

Worries also surfaced when it became clear that domestic violence would increase as the most vulnerable are hit economically and are ordered to stay indoors for extended periods of time. Helplines have indeed received more call-ins.[19] Institutional support for women in vulnerable conditions, be it as housewives, income-earners, parents or spouses, will be a priority in policy making in the near future. Caring for the most vulnerable, as expressed in the family-focused ideal of Penang2030, will have to be more institutionalised especially when it is becoming clear that a rebounding of the economy cannot be expected for quite a while yet.

Adapting institutions for the next normal

Reforming institutions to be better able to handle a prolonged crisis involves more than a mere formal restructuring of these bodies. Success will depend on these reforms being instigated and inspired by a clear understanding among stakeholders, of what the objectives are. For example, if the agricultural sector is to strengthen food security for the people of the state, private sector players will have to be involved in working out the economically sustainable mechanisms for that to happen, without being stifled by bureaucratic rules.

Penang is a major food producer in Malaysia and a key player in the development of aquaculture in Malaysia. Seafood is often considered the cheapest source of protein, and one of the fastest to produce, and on which the Bottom-40 depends for good and affordable nourishment. The heads-up provided by the Covid-19 crisis should stimulate the agriculture sector to upgrade technologically and to localise its supply routes to a significant extent.[20]

The city councils of both Penang Island and Seberang Perai will be under increasing pressure to help manage public hygiene, and to provide effective administrative channels in coming months. This can best be done through digital means, and the push towards e-governance in all its aspects should determine the level of administrative resilience in the future.[21]

As the MCO drags on, one thick silver lining becomes clear to most people. Nature is recovering. The air has become fresher, the noise pollution has dropped sharply, dolphins are again sighted in Penang waters and its rivers have started looking green again instead of different shades of black, birdsong has become louder and birds now dare to appear closer to human habitations.[22] These exciting experiences have been a good reminder for those worriedly locked away in their homes of the irreplaceable value of a vibrant environment. Hopefully, the centrality of liveability to the cultural exceptionalism that Penang society has always tended to claim for itself has become obvious again. A new and healthy balance between keeping the environment clean and green and developing an economy should now be attempted.

New criteria for liveability which combine wealth and health, culture and nature, work and leisure, commonality and diversity can now be worked out – and monitored quantitatively and qualitatively, as is suggested in Penang2030 through the survey instrument called Happiness in Penang (HIP) Index, among other means.

Another major disruption of deep concern to most families is the closing of schools. There are calls for new mechanisms to be worked out so that the education of children can continue even if new waves of the pandemic hit in the near future. Needless to say, online learning and home-schooling have become not only real institutional options for the future, they are already a reality for many in managing the crisis.[23] Even though education policies are a federal matter, aid mechanisms and alternatives should be provided at the state level.

This is even more clearly the case when it comes to the issue of childcare. Parents forced to work at home cannot over a longer period be effective in caring for their young ones at the same time. New rules and support mechanisms that can work for employee, employer and child will have to be developed.

In general, for the Penang State Government to gain the most mileage out of the work it has already done in fighting the disease, the adaptation it should undertake is not only to put the best person on the best job, but to first let the jobs be defined by the problems the crisis forces on it to prioritise.

The portfolio nomenclature of the Penang State executive council should be based on the issues made most pertinent and particular to Penang, and that are being defined by both the damage being done by pandemic, and by the measures that have to be undertaken to fight it.

As a thought experiment, we can imagine a portfolio for public health, one for amenities (including internet access and housing perhaps), another for women affairs, one for digital development, one for federal-state relations, one for the arts and the culture sector separate from tourism, one for economic strategy with sub-divisions for SME development and for MNC management, one for disaster management, another for environmental development (rather than protection), and even one for labour, one for education, and one for youth and sports. This would be a needs-based set of portfolios and not a traditional modular one.

But then, these are just names. They may help in the division and the defining of the areas of responsibility, but what remains important is the efficacy in each portfolio. The names provide focus for the exco members but the ability to have real impact will depend on good communication and serious dialogue between top, middle and bottom strata of society.

Rescuing the people and the economy

Implementing a lockdown may have been challenging, but exiting a lockdown is just as difficult a matter. Deciding on the graduality and the timing for ending movement control has to be a calculated risk, done with clear information to the public being made available in time.[24]

Proper suggestions for standard operating procedures are necessary, and should be adapted to the companies and work places involved.[25]

The importance of reliable information was on the top of most people’s mind once the pandemic became a national matter. To comply with the rules for managing the crisis, people needed to know the details and to understand the reasons behind the rulings. The adoption of the latest information and communication technologies is therefore key; for the community, the state and the private sector.

Central to the proper use of new digital technology is a culture of dynamic data processing. This will be the basis for reliable and resilient policy making. The creation, maintenance and analysis of databases anchor all digital applications, and although the fear of invasion of privacy is a legitimate one, society’s ability to track our movements in time and space has easily become a higher priority in a time of crisis. The problem should therefore be more one concerning democratic mechanisms of checks and balances than principles of individual privacy.

As has been pointed out, Covid-19’s disruption of the economy of Penang affects the services sector more deeply than it does the manufacturing industry. “Rescuing the people” therefore goes beyond health matters to livelihood concerns, especially since 99 percent of businesses in the state are SMEs. Economic planning now becomes a major concern for the state, and the focus should now go beyond getting tourist numbers to go up or FDI figures to break records. A comprehensive rethinking is required, for example, on education directions, options and incentives, on the upskilling and upgrading of the labour force, on high productivity instead of long working hours, on the boon and bane of mass tourism, on the value of heritage beyond being a tourist attraction, and even on getting the most out of FDI for the sake of the local population.

What may also be expected to happen in the short to medium term is that unemployment will begin going up as retrenchments and the cutting down of working hours become a necessary crisis measure for companies based in Penang. The newly unemployed will join the ranks of the self-employed who lost their sources of income almost as soon as the MCO began. The demand for foreign labour can be expected to decrease as well when the economy contracts further and digitalisation takes over.

A silver lining here is found in the possible return of Penang people who in their turn will be losing their jobs in the Klang Valley, in Singapore and elsewhere. Many of these will be looking for qualified work back home in Penang, and this pressure should help stimulate the upgrading of the economy in general.

More research and analysis directed at policy making will need to be done on the longer-term effects of the work-from-home model, on Covid-19 SOPs, on studying-from-home options, on the effect of regular lockdowns on households, on the regionalising of supply chains, on the importance of digital ecosystems, and on the value-add development of the industrial sector.

In the medium term, though (and because the medium term may be expected to be a long span of time in this case) securing food supply chains, raising the level of public hygiene, and strengthening the economic resilience of households and the self-employed, including players in the arts and culture sector, is an imperative.

Empowering the community

In an article published in 6 May 2020 in Penang Institute’s Covid-19 Crisis Assessments series, Penang Chief Minister Chow Kon Yeow clarified that a “whole-of-society” effort is needed for the state and the people to survive the ongoing ordeals.[26] The crisis appears to have enhanced the idea already announced in the Penang2030 Guide that policy making should be democratised and that empowerment of the people has to be the goal of governance in the 21st century[27]; it has also accelerated the need to institutionalise these ideals.

The Penang State Government, it has been reported, has started forming an economic strategy council that includes key players from various sectors, including heads of government agencies, private sector players and academics. This is the right move to make, and should function as the model for the new portfolios suggested in the section above. A portfolio reconfiguration can be effective only if each of the key areas of responsibility and competence is properly liaised with key industry players, relevant experts and concerned citizens.

As we enter the third decade of the 21st century heading for 2030, the main vehicle for developing a society that is resilient and confident in the face of global challenges raised by pandemics, climate change, growing income gaps and geopolitical tensions is digital technology. If adopted wisely, it can be a great socioeconomic leveller; and a society such as Malaysia’s, fixated by internal ethnic tensions and addicted to populist politicking, and long-time victim of the middle-income trap, needs such a cure.

In accelerating the adoption of digital technology, and pushing health and hygiene matters to the forefront of local governance, the struggle against Covid-19 forces the state, under the threat of future global pandemics, towards becoming once again the guarantor of healthcare, education, security and amenities (now including the internet).

Empowering the people, therefore, boils down to the nurturing of a digital community whose members can comprehend, participate and excel in the intensively connected world that is already here. Covid-19 has made this more obvious than any book, however well written, could have done.

Penang found itself well-equipped to manage Covid-19, and if it allows itself to be made deeply cognisant of its strengths and weaknesses through its struggle against the pandemic, the 2030s can see a family-focused green and smart state appear, which can inspire more than the nation.

[1]The author thanks Tan Zhi Xian for valuable research assistance rendered in the writing of this article, and to Ng Kar Yong for diligently gathered statistical data on Penang.

[2]Pelaburan 2019: Pulau Pinang catat FDI tertinggi dalam negara dan sejarah negeri: https://www.buletinmutiara.com/pelaburan-2019-pulau-pinang-catat-fdi-tertinggi-dalam-negara-dan-sejarah-negeri/

[3]Liew Chin Tong: “Wu Lien-Teh: The Malayan who “Squashed the Curve” of the 1910 Pneumonic Plague”. Penang Monthly, March 2020: https://penangmonthly.com/article.aspx?pageid=17219&name=covid19_exclusives_wu_lienteh_the_malayan_who_squashed_the_curve_of_the_1910_pneumonic_plague

[4]Wong Yee Tuan: “Lessons to Learn from Penang’s 1918 Influenza Pandemic”, Penang Monthly, March 2020: https://penangmonthly.com/article.aspx?pageid=17221&name=covid19_exclusives_lessons_to_learn_from_penangs_1918_influenza_pandemic

[5]One could here discuss how Covid-19 in one fell swoop is revealing how far the destruction of state functions throughout the world since the 1980s—and with it, responsible leadership and competent civil services—has come. But that will have to be for another time.

[6]Department of Statistics Malaysia: Main Findings of Special Survey ‘Effects of COVID-19 on the Economy and Companies/Business Firms’- Round 1: https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/cone&menu_id=RkJtOThJSlBJNStOV1liM1JsKzdZUT09. For a discussion on Penang’s case, see Lim Sok Swan: “The Covid-19 Disruption Highlights the Neglected Nature of Arts and Culture Sector in Malaysia”, ISSUES, 9 April 2020 https://penanginstitute.org/publications/issues/the-covid-19-disruption-highlights-the-neglected-nature-of-arts-and-culture-sector-in-malaysia/; and Pan Yi-Chieh: “A Critical Time for Penang’s Fragile Creative Ecosystem”, ISSUES, 18 April 2020: https://penanginstitute.org/publications/issues/a-critical-time-for-penangs-fragile-creative-ecosystem/

[7]Jeffrey Chew: “Penang’s Cruise Tourism Industry: Surviving the Covid-19 Perfect Storm”. Covid-19 Crisis Assessments, 4 May 2020: https://penanginstitute.org/publications/covid-19-crisis-assessments/penangs-cruise-tourism-industry-surviving-the-covid-19-perfect-storm/

[8]Ong Wooi Leng: “Penang Economic Outlook 2020: A Rough Year Ahead”, ISSUES March 2020: https://penanginstitute.org/publications/issues/penang-economic-outlook-2020-a-rough-year-ahead/

[9]See “Media Statement by the Chief Minister of Penang on 12 May 2020 at Komtar, George Town”.

[10]Chow Kon Yeow: “Penang Next Normal has to be a Whole-of-Society Effort”. Covid-19 Crisis Assessments, 6 May 2020: https://penanginstitute.org/publications/covid-19-crisis-assessments/penang-next-normal-has-to-be-a-whole-of-society-effort/

[11]CNA: “Coronavirus may never go away: WHO”. 14 May 2020: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/covid19-coronavirus-who-go-away-12729420?cid=h3_referral_inarticlelinks_24082018_cna

[12]Tony Yeoh: “Fighting Covid-19 with Collaboration and Connectivity in Medical Science and Information Technology”. ISSUES, April 2020: https://penanginstitute.org/publications/issues/fighting-covid-19-with-collaboration-and-connectivity-in-medical-science-and-information-technology/

[13]Steven Sim: “Using Technology during the MCO”, Penang Monthly, March 2020: https://penangmonthly.com/article.aspx?pageid=17246&name=using_technology_during_the_mco

[14]Izzuddin Ramli: “Journalists are Also Essential Workers during Times of Crisis”. Penang Monthly, March 2020: https://penangmonthly.com/article.aspx?pageid=17216&name=journalists_are_also_essential_workers_during_times_of_crisis

[15]Penang Institute: “Securing Food Supply and Strengthening Social Resilience in Penang during the Covid-19 Crisis”. Covid-19 Crisis Assessments, 27 March 2020: https://penanginstitute.org/publications/covid-19-crisis-assessments/securing-food-supply-and-strengthening-social-resilience-in-penang-during-the-covid-19-crisis/

[16]Yeong Pey Jung: “Poor Households Bear the Economic Brunt of Covid-19”. Penang Monthly, March 2020: https://penangmonthly.com/article.aspx?pageid=17199&name=poor_households_bear_the_economic_brunt_of_covid19

[17]Yap Jo-Yee: “Fiscal Challenges Await Most Governments”. Penang Monthly, April 2020: https://penangmonthly.com/article.aspx?pageid=17257&name=covid19_fiscal_challenges_await_all_governments

[18]Choong Pui Yee: “Covid-19: Impacts on the Tertiary Education Sector in Malaysia”, Covid-19 Crisis Assessments. 8 May 2020: https://penanginstitute.org/publications/covid-19-crisis-assessments/covid-19-impact-on-the-tertiary-education-sector-in-malaysia/

[19]Yeong Pey Jung: “Domestic Violence and the Safety of Women during the Covid-19 Pandemic”. Covid-19 Crisis Assessments. 25 April 2020: https://penanginstitute.org/publications/covid-19-crisis-assessments/domestic-violence-and-the-safety-of-women-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

[20]Negin Vaghefi: “The Heavy Impact of Covid-19 on the Agriculture Sector and the Food Supply Chain”. Covid-19 Crisis Assessment. 19 April 2020: https://penanginstitute.org/publications/covid-19-crisis-assessments/the-heavy-impact-of-covid-19-on-the-agriculture-sector-and-the-food-supply-chain/

[21]Tan Lii Inn: “Smart City Technologies Take on Covid-19”. ISSUES, March 2020: https://penanginstitute.org/publications/issues/smart-city-technologies-take-on-covid-19/.

[22]Nursyazana Khidir Neoh: “Nature Breathes Better as Covid-19 Keeps Humans Indoors”. Penang Monthly April 2020: https://penangmonthly.com/article.aspx?pageid=17249&name=nature_breathes_better_as_covid19_keeps_humans_indoors

[23]Kristina Khoo: “Schools May Be Shut, but the Learning Continues”. Penang Monthly March 2020: https://penangmonthly.com/article.aspx?pageid=17215&name=schools_may_be_shut_but_the_learning_continues

[24]Timothy Choy, Yeong Pey Jung and Yap Jo-Yee: “Some suggestions Regarding Penang’s Post-Covid-19 Economic Restart”, Covid-19 Crisis Assessments, 16 April 2020: https://penanginstitute.org/publications/covid-19-crisis-assessments/some-suggestions-regarding-penangs-post-covid-19-economic-restart/

[25]Ong Siou Woon, Tan Zhi Xian and Tan Bee Eu: “Guidelines for the Resumption of Workplace Operations Post-MCO”. Covid-19 Crisis Assessments, 3 May: https://penanginstitute.org/publications/covid-19-crisis-assessments/guidelines-for-the-resumption-of-workplace-operations-post-mco/

[26]Chow Kon Yeow: “Penang Next Normal has to be a Whole-of-Society Effort”. Covid-19 Crisis Assessments, 6 May 2020: https://penanginstitute.org/publications/covid-19-crisis-assessments/penang-next-normal-has-to-be-a-whole-of-society-effort/

[27]Penang2030 Guidebook. Penang State Government, 2019: https://www.penang2030.com/files/The%20Penang2030%20Guide_First%20Edition%202019_eBook_.pdf

APPENDIX: Stimulus Packages during Covid-19, Penang State Government