EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The Covid-19 pandemic is expected to exacerbate Malaysia’s skills mismatch if unemployed or underemployed graduates are not reskilled while waiting for recovery.

- There is evidence that non-graduates are at risk of being crowded out from semi-skilled and unskilled jobs. This is due to an increasing rate of overeducation.

- On the demand side, fiscal and monetary policies targeted at skill-intensive industries will aid job creation of skilled jobs. Employers will do well to invest in digitalisation, innovation and productivity growth, and in enabling effective remote work.

- On the supply side, more collaboration is needed between public and private actors to reskill the workforce, reform education institutions to achieve higher graduate quality, and improve transmission of information between employers and students.

- Furthermore, impact evaluation of existing government programmes is required to build accountability between implementers and funders.

INTRODUCTION[1]

There is a developing sentiment over recent years that graduate unemployment is getting out of hand. Indeed, the national rate of graduate unemployment is consistently above the unemployment rate for the rest of the population, driven primarily by fresh graduates 24 years old or younger, whose unemployment rate in 2019 was at an astoundingly high 17.2% (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2020).

The dire situation has led policymakers to question if there is a skills mismatch in the Malaysian graduate[2] labour market (Darusman, 2020; D’Silva, 2020; Malay Mail, 2020), and if so, what it means for young and educated jobseekers, especially in times made more uncertain by the Covid-19 pandemic.

GRADUATES SKILLS MISSMATCH

Skills, as defined by the OECD (2017), refer to both cognitive and non-cognitive abilities and to abilities that are specific to a particular job, occupation or sector (technical skills). Broadly speaking, at the macro level, skills mismatch (Eurostat, 2016) in the context of the graduate labour market implies:

a) qualifications not matching the needs of the region (vertical mismatch); and

b) fields of study not corresponding to jobs that are available (horizontal mismatch)

Skills mismatch amongst graduates is an important issue to address for several reasons. Firstly, it leaves skilled vacancies open for longer. These unfilled positions impede firm productivity in general, and this is especially true for skilled positions that are needed for innovation and expansion.

Moreover, a surplus of particular skills could lead graduates from certain fields to look towards semi-skilled roles for employment, crowding out non-graduates.

At the same time, a misallocation of skills also means that graduates are unemployed for longer periods of time while they look for suitable jobs. If unemployed for an extended duration, job seekers may eventually become disheartened and leave the labour force entirely, raising the percentage of those permanently unemployed, or they may face a situation where their skills are obsolete due to lack of use or to technological development.

Ultimately, a skills mismatch acts as a drag on the country’s growth as a whole.

In a survey of Malaysian workers, Lim et al (2018) found that as high as 64% of workers in semi-skilled jobs are overeducated. Zakariya (2014) reported that 31-35% of graduates are working in fields that do not correspond to their studies, building on Lim et al’s (2008) finding that a large proportion of these mismatches stem from graduates in social sciences.

Understanding whether there is a skills mismatch, and which kind, also matters for policymakers’ choice of tools. Wrong choices may create structural unemployment that cannot be affected by monetary policy such as interest rate cuts, aimed at stimulating the economy and at job creation.

UNDERSUPPLY OF HIGH-SKILLED JOBS

Two key findings for this study are:

1) There is increasing mismatch in the form of overeducation.

2) There are also indications that non-graduates are at risk of being crowded out from semi-skilled and unskilled jobs.

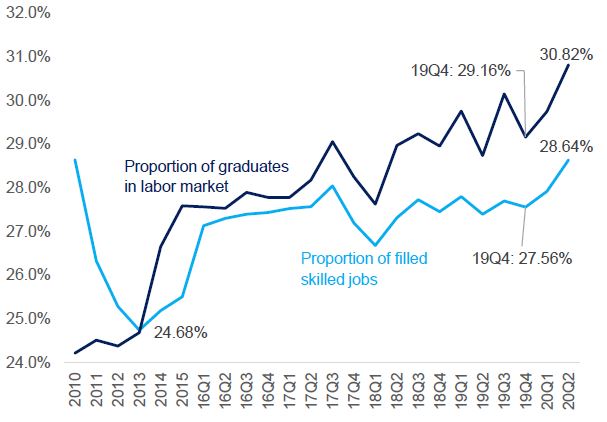

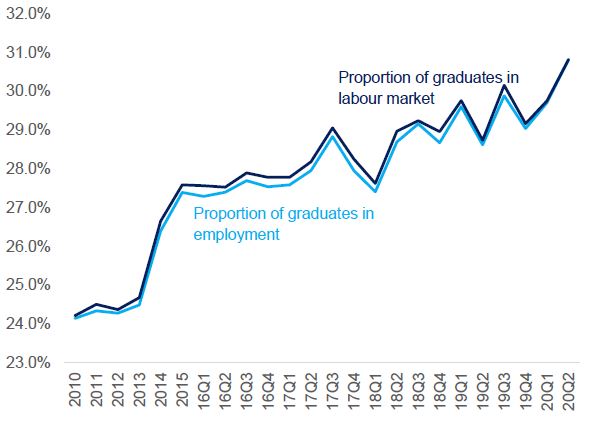

Figure 1 shows that the proportion of employed graduates amongst all employed workers has typically been slightly lower than the proportion of graduates in the labour market. Small discrepancies in such a comparison are not surprising, given that friction in the job search process often can arise from imperfect information, relocation costs, etc.

Figure 1: Proportion of graduates in employment shadows their proportion in the labour force

Very minor disparities between the proportion of graduates in the labour force and those in employment had always existed. This gap closed in 2020 due to changes in work conditions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Source: Author’s own calculations based on the Labour Force Survey, Department of Statistics Malaysia

In 2020, we see this narrow gap closing due to changes in work arising from the pandemic. This can be explained by employers retaining roles that allow remote work, which are typically skilled jobs (Brynjolfsson et al., 2020). It is also likely that workers with lower qualifications dropped out from the labour force when the movement control order was imposed in 2020 Q1, despite wanting to work. This happened most dramatically within the tourism industry and wholesale/ retail trade subsector (Choy et al., 2020)[3]. Alternatively, employers may be responding to looser labour market conditions by raising qualification requirements for typically non-graduate jobs.

We examined the extent of skills mismatch by comparing the proportion of graduates with the proportion of filled jobs requiring tertiary education. The supposition is that if all employed graduates held skilled jobs, we would expect to see a figure similar to that in Figure 1. On the other hand, if a skills mismatch exists, it would show up in the form of a larger gap. Indeed, the analysis based on Figure 2 shows evidence of a skills mismatch.

In 2010, the proportion of skilled jobs was disproportionately higher compared to graduates in the labour force. This suggests that there was an undersupply of graduates relative to skilled jobs (undereducation).

However, this situation reversed in 2013. Since then, there has been a growing trend of overeducation. The proportion of graduates in the labour market has been larger than the proportion of jobs requiring tertiary education, and this gap is growing[4]. Taken together with Figure 1, this shows that tertiary-educated workers have been increasingly taking up semi-skilled or unskilled jobs more suited for non-graduates[5].

Figure 2: Growing overeducation amongst graduates since 2013

Since 2013, overeducation has existed in the graduate labour market, intensifying in recent years.

Source: Labour Force Survey, Department of Statistics

It is key to note that the issue of overeducation is not recent. Even prior to the severe economic contraction in 2020, there is reason to believe that the growing gap between 2013 and 2019 is due to an ongoing dearth of skilled jobs (or equivalently, a surplus of graduates). Figure 2 shows that the skills distribution of filled jobs has not kept up with the changing landscape of the labour force. In 2013, 24.7% of the labour force consisted of graduates. This rose to 29.2% by the end of 2019, an increase of 4.5 percentage points. In comparison, the proportion of skilled filled jobs increased by only 2.9 percentage points (24.7% to 27.6%).

Alternatively, perhaps skilled jobs are increasing, but it is simply difficult to fill them. This could be due to a horizontal mismatch, unrealistic salary expectations from graduates, educated but underskilled fresh graduates, or prohibitive reskilling costs. Some of these are better substantiated by evidence than others.

Regardless, difficulty in filling roles would be seen in high vacancy rates, reflecting a shortage of qualified/ suitable candidates. However, this does not seem to be the case. Considering the fact that vacancy rates of skilled jobs were low and falling between 2016 and 2019, it appears that the immediate problem is that the economy cannot produce skilled jobs quickly enough, notwithstanding the recent economic downturn.

If this is the case, then policymakers need to look for reasons why sectors have been slow to shift away from labour-intensive production methods, and towards knowledge-intensive ones. Graduates with skills that do not match those in demand (Lim et al., 2008; Zakariya, 2014) and their lack of experience or skills (ILMIA, 2016), could be the root factor limiting employers’ ability to expand operations or innovate, thereby limiting job creation. Another constraint may be low wages which simultaneously incentivise labour-intensive production methods and diminish the overall quality of skills by encouraging human capital flight.

In brief, overeducation is indicatory of a lack of skilled jobs, itself symptomatic of deeper underlying issues. These are likely to be a combination of a horizontal mismatch, underskilling, and low wages.

SKILLS MISMATCH AND COVID-19

A skills mismatch matters not merely because it imposes negative effects on graduates themselves[6] but because it creates negative externalities for the rest of the labour force and the health of the economy as a whole. On top of these, accelerated changes brought on by the pandemic in the way people work and in the skills demanded, exacerbate the mismatch, therefore intensifying the effects of it.

1) Non-graduates may experience crowding out from jobs suited for their skill level. Becker (1962) proposes that wages increase with marginal productivity of labour. Hence, when there is a surplus of skilled labour like what is being suggested for Malaysia, the marginal productivity of labour will fall and so will the wages it commands. Employers then take advantage of lower wages and substitute semi-skilled workers with skilled workers

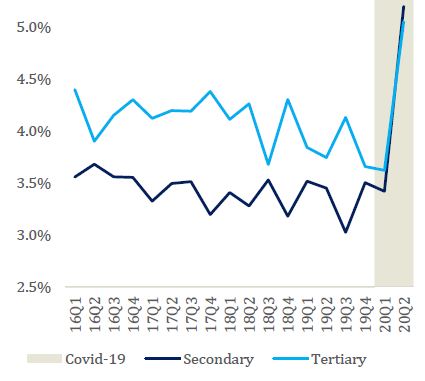

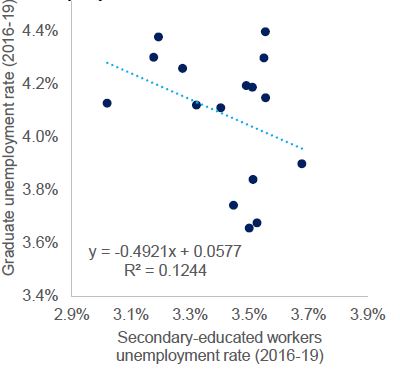

Based on how unemployment rates of secondary-educated workers in normal times (prior to the Covid-19 pandemic) form a mirror image of graduate unemployment rates (Figure 3) and that both are negatively correlated (Figure 4), it is plausible that secondary-educated workers risk being crowded out from semi-skilled occupations by graduates. However, more research needs to be done on this crucial point to make sure that the relationship is not a spurious one.

Figure 3: Unemployment rate of graduates and secondary-educated workers

Figure 4: Correlation between graduates and secondary-educated workers’ unemployment rates

The unemployment rates of graduates and secondary-educated workers are typically negatively correlated, prior to the pandemic (greyed out area in Figure 3).

Source: Author’s own calculations; Labour Force Survey, Department of Statistics Malaysia

Becker also notes that people eventually reduce their investment in education in response to lower wages for the educated. This creates another dilemma because it is far from any policymaker’s mind to have an economy where workers are not incentivised to invest in higher education as returns are low.

2) Just as crucially, a persistent skills mismatch, if unaddressed, creates a greater mismatch, which holds back innovation and growth. Extended duration of unemployment leads to skills decay, making it harder for jobseekers to find skilled work in the future (Pissarides, 1992). At the extreme, jobseekers become disheartened by the job-hunting process, and eventually leave the labour force, effectively locking away a portion of society’s skill supply.

Graduates who do find long-term employment, but in jobs that under-utilize their skills (underemployment), risk skills decay or obsolescence because of a lack of opportunities to practise them (Van Loo et al., 2001).

3) High rates of mismatch and graduate unemployment disincentivise skilled individuals from remaining in Malaysia for fear of not being able to obtain suitable work (World Bank, 2011). It drives human capital flight, for those able to migrate.

In all cases, society experiences loss in human capital, which acts as a drag on the innovation and labour productivity required for economic growth.

Perhaps most pressing now are the threats of skills decay and skills obsolescence occurring. These are real risks in the face of a protracted recession such as the current one[7].

Moreover, the pandemic has radically altered work arrangements and skills demanded by employers. The accelerated shift towards digital solutions, mainly to reduce physical contact and to boost business resiliency (Brynjolfsson et al., 2020; Dannenberg et al., 2020; Raj et al., 2020), means that new roles created will require different sets of skills and increased agility from both employers and employees. If graduates are not reskilled now, Malaysia’s market for skilled labor will find itself faced with a worsened mismatch when the worst of the pandemic is over.

POLICY SUGGESTIONS

Although the issue at hand is an escalating graduate unemployment rate as a result of the recession, the underlying problems cannot be ignored. The results of this study highlight the fact that overeducation amongst graduates is rising steadily, due to a lack of jobs, likely caused by a horizontal mismatch, underskilled graduates and undesirable wage levels.

Demand side policies

1) On the demand side, broad tools such as monetary policy and government spending on infrastructure can stimulate job creation activity, and are necessary during a recession. Given that it is the slow growth of skilled jobs that is the immediate cause of Malaysia’s skills mismatch, tackling the problem in the short run means directing a part of job creation efforts towards skill-intensive industries.

2) Employers, especially those in low-productivity sectors like agriculture, construction, and services need to build capacity for innovation and productivity growth by creating structured pathways for employees to upskill themselves, even if starting from unskilled roles, to ensure that graduates and non-graduates who begin from these roles have clear routes for progression. Sustainable wage growth and job creation must necessarily be led by innovation and productivity growth. It is crucial to recognise that this does not concern only skilled jobs.

3) Digitisation of work is also crucial for business continuity and productivity growth. Remote work, for example, will enable more graduates to remain employed or find employment in knowledge-based roles during the pandemic. However, this should be done with the awareness that employees working from home face a new set of challenges which should be adequately mitigated.

Employers play a key role in facilitating this by restructuring work policies to provide flexibility and support for employee needs, and providing employees with the appropriate technologies (hardware, software, stable internet connection) that enable offsite work.

Supply side policies

1) Tackling supply-side constraints in the short term (horizontal mismatch) involves reskilling unemployed and underemployed graduates.

2) In the long term, community stakeholders must hold higher education institutions more accountable to the quality of graduates they produce, and labour market information that the institutions pass on to students before enrolment.

3) It is also essential to improve the transmission of information between employers and students who need to make decisions about their future studies and careers. This involves industrialists and educators creating platforms or channels that allow secondary students more visibility into the labour market, or providing more work experience days.

Commendable initiatives led by the government to upskill employees, digitise work, and build capacity already exist under agencies such as Malaysia Digital Economy Corporation (MDEC), Ministry of Entrepreneur Development and Cooperatives (MEDAC), Digital Penang (DP), and Human Resources Development Fund (HRDF). However, effective implementation still depends on increasing uptake rate, especially amongst SMEs from the B40 group, having frequent programme evaluations to understand impact, and most crucially, having processes that create accountability between implementers and funders (tax-payers and/or other actors).

CONCLUSION

The analysis confirms skills mismatch occurring in the form of overeducation, which is directly caused by a skills surplus owing to the lack of skilled jobs. This Covid-19 recession will be deep and long compared to previous downturns, and the stark reality is that it will exacerbate Malaysia’s skills mismatch if unemployed or underemployed graduates are not reskilled while waiting for recovery. That being said, long-term measures to deal with root issues are just as important.

For list of references, kindly download the document to view.

Editor: Ooi Kee Beng

Editorial Team: Sheryl Teoh, Tan Lii Inn, Alexander Fernandez, and Nur Fitriah (Designer)

[1] This article looks at the underlying challenges that the graduate labor market faces, and tries to understand how they will interact with the economic downturn. Data for the study are taken from the Labour Force Survey, Graduate Statistics, and Employment Statistics, published by the Department of Statistics Malaysia. The time period studied is 2010-2020 Q2. A few simplifying assumptions are made. Firstly, graduates apply for skilled positions (MASCO 1-3), secondary-educated workers apply for semi-skilled positions (MASCO 4-8), and primary-educated or unschooled workers apply for elementary roles (MASCO 9). Secondly, filled jobs are taken to be an indicator of a match in skills offered and skills demanded for a job. This is based on the Pissarides-Diamond-Mortensen model (Mortensen & Pissarides, 1994) where employers post vacancies, and employees undergo a job hunt process. Filled vacancies are the outcome of a match. According to Brunello and Wruuck (2019), a skills mismatch can be inferred by comparing the distribution of employment by qualification as a proxy of labour demand with that of the working age population (proxy of labour supply). This is the concept employed in this article.

[2] The term ‘graduate’ refers to any person who has completed tertiary-level education.

[3] Nationally, the majority of jobs in the “accommodation and food service activities” and “wholesale/ retail trade” subsectors are semi-skilled and unskilled (80.8% and 81.4% respectively) (ILMIA, 2016).

[4] As a simple means of robustness-testing, data of filled jobs from Employment Statistics (2020) were used, which were taken from samples different from those of the Labour Force Survey. The same trend is observed.

[5] Indeed, between 2016 and 2019, despite downward-trending graduate unemployment rates, the proportion of graduates hired for skilled work fell by 3.8 percentage points in total. Graduates employed in semi-skilled work on the other hand increased by 3.5 percentage points, and by 0.3 percentage points for unskilled work.

[6] A large volume of literature explores how overskilling (less so for overqualification) is a cause for poor job satisfaction, wage penalty, and lower productivity (Allen & van der Velden, 2001; Kler, 2006; McGowan & Andrews, 2017).

[7] The arrival of a vaccine, distribution and immunisation efforts will still take months at the very least (Scudellari, 2020). Moreover, owing to its global nature, and the deep wounds that the pandemic is creating in economies worldwide in terms of unemployment, output, and debt burdens, a V-shaped recovery is unlikely. Instead, recovery will take place in short bursts (Bremmer, 2020).

You might also like:

![Penang Next Normal has to be a Whole-of-Society Effort]()

Penang Next Normal has to be a Whole-of-Society Effort

![Covid-19: Impact on the Tertiary Education Sector in Malaysia]()

Covid-19: Impact on the Tertiary Education Sector in Malaysia

![Securing Food Supply and Strengthening Social Resilience in Penang during the Covid-19 Crisis]()

Securing Food Supply and Strengthening Social Resilience in Penang during the Covid-19 Crisis

![Targeted Support Needed to Keep Penang's SMEs Afloat]()

Targeted Support Needed to Keep Penang's SMEs Afloat

![A Spotlight on Migrant Workers in the Pandemic]()

A Spotlight on Migrant Workers in the Pandemic