By Dr Rahida Aini Mohd Ismail (Project Researcher); Justin Teoh (Intern) [1]

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

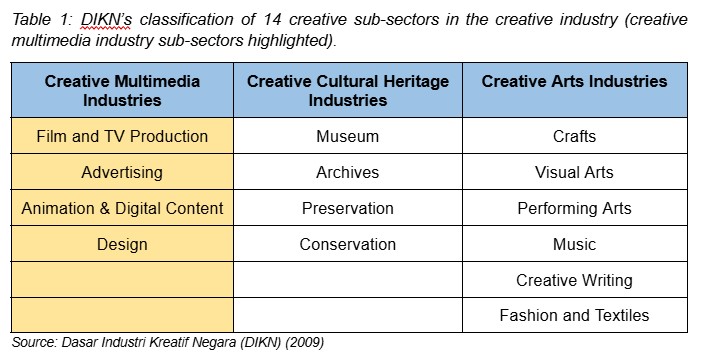

● The National Creative Industry Policy (DIKN) framework categorises creative industries into three main sectors: Creative Multimedia, Cultural Heritage, and Cultural Arts. Its goal is to enhance the creative economy. However, it encounters difficulties in standardising its various sub-sectors.

● The Malaysian film industry faces challenges such as linguistic diversity, funding constraints, and limited creative freedom; this results in a fragmented market and in underperformance compared to foreign films.

● Strict censorship and funding difficulties pose significant challenges to filmmakers in Malaysia, hindering their creativity and economic viability. To foster a vibrant and commercially successful creative industry, it is essential to relax censorship regulations and increase financial support.

● This article addresses current challenges and examines policies adopted by other countries for developing the creative industries sector. The study employs a comparative analysis and synthesis of the literature on creative industry concepts and policies, advocating for a medium-to-long-term approach to guide sustainable creative industry cluster policies.

● Policymakers need long-term strategies to support filmmakers, improve creative output, and enhance business understanding. Learning from successful international policies is crucial.

Global Trends

The global multimedia creative industry is thriving, and Malaysia needs to participate actively in it. Recent data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s (UNCTAD) 2024 Creative Economy Outlook shows that in 2022, creative services exports worldwide were $1.4 trillion (29% increase since 2017) while creative goods exports worldwide were $713 billion (a 19% increase since 2017)[2]. In the same report, UNCTAD also mentions that Malaysia’s creative goods exports put itself as the eighth best among developing countries, attributing “software, video games and recorded media” for contributing 62% of its $12.5 billion export value.

There exists an opportunity to leverage Penang’s technological and infrastructural developments to benefit Malaysia’s performance in the multimedia creative industry market.

This policy brief provides a brief overview of the multimedia industry’s policy landscape in Malaysia, highlight promising achievements of today’s local artists and filmmakers within international spheres, and outline policy recommendations that will respond to industry challenges productively. Throughout the discussion, we include case studies and analyses that illustrate how the policies benefit other economies around the world.

Creative Multimedia Industries in Malaysia: Challenges and Opportunities

Malaysia’s creative industry encompasses various fields, which not only creates significant job opportunities but also encourages artistically oriented students to hone their creative and critical thinking skill sets. In the film industry, for instance, the creative works of directors P. Ramlee and Yasmin Ahmad were known to tackle complicated societal topics while emphasising good social values; as such, their legacies continue to inspire and educate both audiences and artists alike.[3]

Recognising the profound impact such ground-breaking work has had on the nation’s creative and economic landscape, the Malaysian government launched the 2010 National Creative Industry Policy (DIKN), which aimed to empower the creative industries by setting principles that would raise public awareness, improve output quality, and enlarge the domestic or international market.[4] Apart from outlining 11 strategies and some action plans, the DIKN categorises creative offerings into three main sectors as shown below, encompassing a total of 14 different sub-sectors. For our present scope, we will provide further discussion about the sub-sectors within the creative multimedia industries umbrella.

Policy scholars such as Khoo Suet Ling make the valid criticism that the DIKN’s holistic scope does not lend itself to systematic integration with urban development, thereby diminishing any cultural emphases in policy agendas[5]. As a policy text, it assumes that creativity is inherent in the output of these industries,[6] homogenises ‘preservation’ and ‘conservation’ as creative activities when it involves various other disciplines and provides little differentiation.[7] While awareness of the creative industries’ activities has emerged from the DIKN, the resultant generalisation of said activities makes it difficult to produce policy prescriptions that are SMART—i.e., specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-sensitive.

Indeed, the DIKN can only remain as ‘a mere blueprint without running its actual course’ because it cannot provide sufficient guidelines for stakeholders to navigate logistical hurdles such as bureaucracy, poor coordination, mistrust and a perception that components of the industry are being marginalised from national development’.[8] For instance, research by Rosli Borhan, Zairul Anuar and Sharip Zainal (2022) shows that the absence of policy-level accountability has put workers within the Malaysian film industry at risk of payment delays and unfair salaries, which can demotivate workers and impact the quality of production.[9] Also relevant is Abdul Razak and Ahmad Syuhaidi’s 2018 research, where they found that human capital problems such as the following can spiral and perpetuate negative realities of working in the industry: insufficient funds and capital, poor script quality, a lack of scripts in the FINAS script bank, harsh competition for broadcasting slots, and narrative weaknesses.[10]

This critique gives voice to a perceived helplessness that prevents the formation of substantial creative industry policies. Khoo says that ‘the absence of a distinctive city-level policy [cannot] steer holistic urban development’.[11] Professional respondents of her study reported how creative industries are viewed as “filler in programmes” that do not receive any write-up; even if they do, they are underwritten as elements, not as distinctive policies.[12]

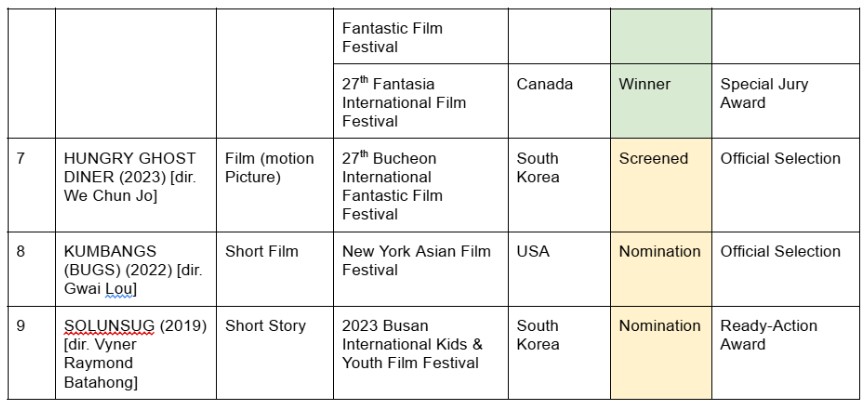

Arguably, one can attribute this policy apathy to the visible strides that Malaysians have taken within the creative industry. For instance, we can look at the international success of its filmmakers. Malaysian directors from all backgrounds brought home worldwide recognition through various film screenings and prizes, including the renowned Cannes Film Festival in France. These achievements as shown in Table 2 below illustrate the robust creative potential within Malaysia’s film industry. Although many awards were for short films, these achievements highlight the ability of Malaysian filmmakers to create compelling visual narratives, pointing to an opportunity for Malaysia to emerge as a significant player in the global creative multimedia industry.

Another example would be the animation and digital content sub-sector, which leverages the latest technological advancements to produce innovative products. Major examples include Les’ Copaque Productions’s popular 3D-animated TV series “Upin and Ipin” and Animonsta Studios’s animation franchise “BoBoiBoy”. These sectors are gaining significant legitimacy and validation from the public, attracting valuable foreign investment. However, despite its integral role for the industry, the local film and TV production sub-sector remains fragmented.

To see how the Malaysian government demonstrates an awareness and willingness to help, one does not need to look further than the Digital Content Ecosystem (DICE) policy, which is spearheaded by MDEC. This policy aims to accelerate the animation and digital content sub-sector as a driver of economic growth in Malaysia by strengthening human capital, enhancing the industry’s value chain, driving the commercialisation of intellectual property (IP), and elevating the nation’s ecosystem to global standards. The policy focuses on building local talent and companies, attracting investments and fortifying the ecosystem through partnerships between the government and the private sector. Given the success of the DICE policy, there is a pressing need to revise the policy governing the film industry. The primary objective of the policy is to promote creativity and ensure sustainable economic and social benefits. Despite the policy’s generally positive impact over the past decade, the vibrancy of Malaysia’s creative economy still lags behind Asian countries such as Thailand and Indonesia.[14]

Whichever the case, substantial investments and financial support in this industry in the form of sufficient funds and financial assistance is crucial to developing, producing, and marketing creative works.

Policy Challenges in Creative Multimedia Industries

A 2019 study that explored the multimedia creative industry sector on local film performance revealed that the Malaysian film industry struggles to establish a significant presence in its domestic market. However, various programmes through the Digital Content Fund (DKD) such as the Creative Industry Economic Immediate Action Plan (Pelaksana), Borneo Pitch, Creative Industry Micro Financing for Creative Entrepreneur, and others, help production companies produce creative content including dramas, films, documentaries, short stories and so on by Finas, local films (MFs) underperform when compared to foreign films (FFs). This consistent underperformance of MFs at the local box office highlights the need for further policy intervention to protect and boost local film revenues amidst the overwhelming presence of imported FFs. The study offers an objective assessment of the local film industry’s status and the effectiveness of existing policies designed to enhance its performance.[15]

Meanwhile, ‘Maryam Pagi Ke Malam’, a local film that premiered at the prestigious International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR) in 2023, has yet to be shown in Malaysian cinemas despite receiving international acclaim. Badrul Hisham, the director and screenwriter of the movie, claims that the film has received little attention from both the government and the public, likely due to its sensitive themes.[16] Despite Malaysian local films receiving less recognition in their home country, there is a noticeable emergence of creative filmmakers in the country but they somewhat had had to seek better opportunities abroad.

The creative industries have great potential to boost the economy and improve the quality of life in Malaysia. However, creative autonomy in the Malaysian film industry is limited, despite a surge of first-time directors making their mark at film festivals.

Success of Malaysian Directors Abroad

Beyond critical acclaim, Malaysian directors are capable of producing box office hits overseas. Penang-born director Sam Quah is relatively unappreciated in Malaysia, yet his crime thriller ‘Sheep Without a Shepherd’ reportedly grossed nearly USD 200 million in China. Similarly, Chiu Keng Guan, who directed the award-winning film The Journey—the highest-grossing local film in 2014 with MYR 17 million— both found success in China.[17] Both directors built successful careers abroad due to unfavourable conditions in their home country.

These directors’ success abroad illustrates the importance of a supportive environment for creative multimedia clusters. In international markets with fewer censorship constraints and better funding opportunities, creative clusters can flourish, enabling filmmakers to achieve greater artistic and commercial success.

Iskandar Malaysia Studios: A Model for Success

Johor is home to Iskandar Malaysia Studios (IMS), a premier destination for filmed entertainment production in Southeast Asia. IMS features state-of-the-art film stages, TV studios, water filming tanks, and extensive production support facilities, including sound stages, backlots, production offices, post-production facilities, props rental, wardrobe, makeup, hair, dressing rooms, screening rooms, and workshop space. This studio was established to catalyse and internationalise the Malaysian creative industry and to position the Iskandar region as the creative industry’s hub. Notable productions at IMS include Netflix’s 2014 drama series Marco Polo and the Hollywood film Crazy Rich Asians. Penang is without any such resources.

Why the Need for Creative Clusters in Penang?

Given that Penang is home to various small-to-medium production companies, such as Filmmakers, Tickle U, Image Farm, Lee Video Productions, Peanut Butter Creative Studios, Bold Media, Rising One Media and many more, establishing such a hub would centralise their business activities and foster creative freedom, entrepreneurship initiatives, and see the emergence of new fields. As our comparative analysis will demonstrate later, such a hub also facilitates the blending of knowledge and skills across different creative industries, promoting cross-disciplinary collaboration and innovation. This synergy can lead to the development of unique creative outputs that may not arise in isolated environments.[18]

The presence of a facility similar to Iskandar Malaysia Studios (IMS) in Penang could significantly boost the local creative industry, attract international productions, and consolidate the presently scattered efforts in entertainment production. A centralised hub would provide a comprehensive support system for creative industries and create a vibrant ecosystem for the arts, complementing existing venues like Hin Bus Depot, which already contributes to the local cultural scene with performances, movie screenings, markets, and more.

Creative industries rely heavily on technological innovations. Modern filmmaking, for instance, utilises tools such as Computer-generated imagery (CGI), animation, virtual reality, and drone cinematography, all deeply rooted in STEAM fields. While most developed countries have leveraged the benefits of creativity and innovation to achieve high-income economies, developing countries like Malaysia have struggled to replicate this success. Educating students in these technologies through a STEAM framework can inspire them to push the boundaries of conventional creative works. Malaysia, with its burgeoning tech industry, stands to benefit immensely from producing more creative individuals proficient in the latest technological advancements. This synergy can lead to ground-breaking artistic works that put Malaysian creatives on the international map.

Penang2030’s master plan aims to boost the creative economy by enhancing arts facilities (Pillar A4) and fostering a supportive ecosystem for creative industries (Pillar B4). Key targets include doubling community arts productions, achieving a 50% survival rate for creative start-ups, and increasing the creative economy’s GDP contribution from under 1% to 5%. Establishing a centralised creative hub would align with these goals, providing the necessary infrastructure and support to ensure the growth and sustainability of the local creative industry.

The creative industry can facilitate all these developments. The 12th Malaysian Plan’s (2021-2025) Strategy A4, “Maximising the Potential of the Creative Industry,” suggests that the incorporation of creative industries provides rewarding job opportunities and increases revenue. To achieve this, developing a holistic creative industry ecosystem is essential.

Penang2030 includes agenda item B4, which aims to “foster an ecosystem that nurtures creative industries and niche business services by developing talents, attracting skilled Penangites back, and incentivising start-ups and social enterprises” (2019). PETACE chairman YB Wong Hon Wai, whose office aims to establish Penang as the “artistic hub of Malaysia,” echoes this sentiment. He encourages stakeholders to leverage local assets in ways that showcase the state’s distinctions in arts, culture, entertainment, and gastronomy.

Implicit in these aspirations is the need to develop Penang’s creative economy. We propose the systemisation of its existing creative hotspots as “clusters”—distinct geographic zones where companies and talent in the field concentrate strategically to optimise innovation and provide unique goods and services. This paper examines clustering literature, including case studies, policy reports, and research articles from major and peer countries, to articulate the key factors, opportunities, and challenges as they relate to Penang’s local context.

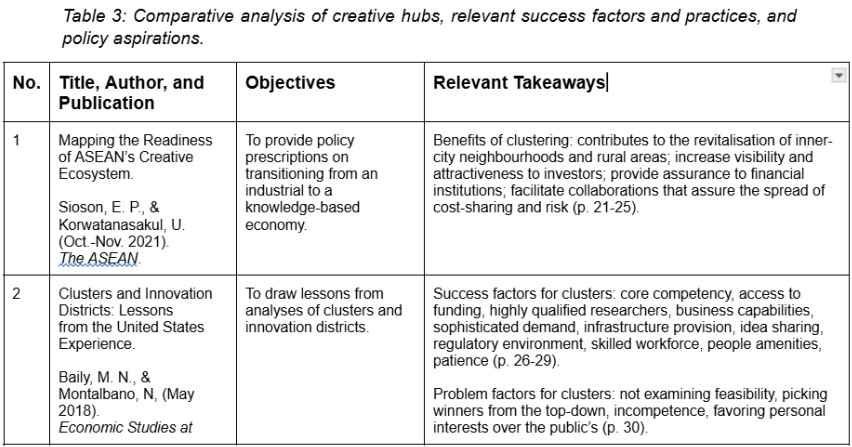

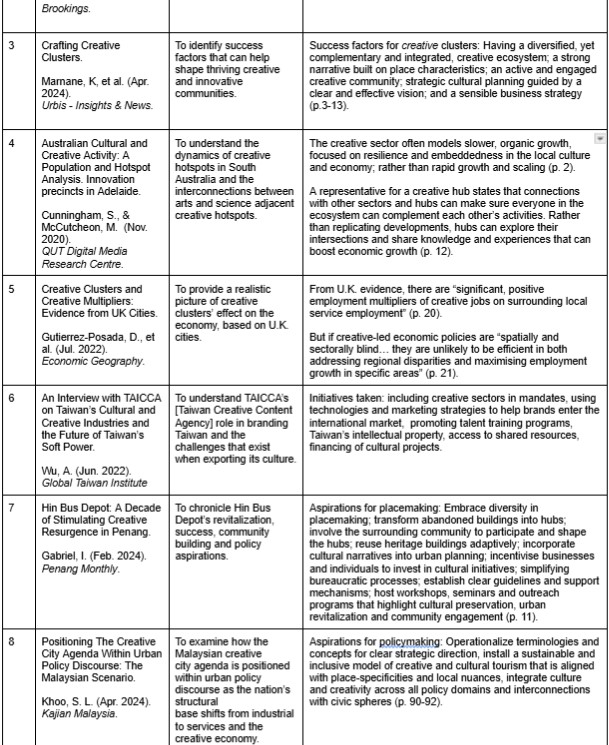

Comparative analysis

In Europe, cities such as Milan, London, and Paris have developed creative industries and built creative clusters relatively early, and hence they have gradually become global creative centres. To gather a repository of policy suggestions to direct Penang’s leadership efforts, we referred to policy briefs and reports on creative hubs and industries, as well as relevant sources such as press releases, articles and academic papers that present relevant initiatives and success factors. Table 3 below presents this repository for policymaking reference and comparisons.

Penang can draw several key lessons from the experiences and recommendations outlined in the provided sources to enhance its policy for creative clusters. Firstly, the benefits of clustering and integration are evident in diverse and integrated ecosystems seen in other regions. Marnane, Saul, Luki and Trantis (2024) and Cunningham and McCutcheon (2020) highlight that a well-rounded ecosystem which integrates various sectors and fosters collaboration, enhances resilience and embeds the creative industry deeply into the local culture and economy. This integration not only revitalises inner-city neighbourhoods and increases visibility but also attracts investors and facilitates cost and risk-sharing collaborations, as noted by Sioson and Korwatanasakul (2021).

Success factors for creative clusters, as identified by Baily and Montalbano (2018), include core competencies, access to funding, and robust infrastructure. Penang should ensure these elements are in place to support its creative clusters. Additionally, Marnane et al. (2024) emphasise the importance of an engaged creative community and strategic cultural planning. Penang should therefore foster an active creative community and develop clear, effective cultural policies.

Addressing potential problem factors is also crucial. Baily and Montalbano (2018) caution against top-down approaches and favouring personal interests over public needs. Penang should adopt inclusive policies that consider the needs and feedback of the entire creative multimedia community. Furthermore, successful clusters often require patience and realistic assessments of feasibility. Penang should adopt a long-term perspective, ensuring that initiatives are viable and grounded in practical realities.

Knowledge sharing and collaboration are essential for the success of creative clusters. Cunningham and McCutcheon (2020) stress the importance of connecting with other sectors and hubs. Penang should facilitate knowledge sharing and collaboration between different creative sectors – Film and productions, advertising, animation and digital content, and design and related industries to enhance overall economic growth. Gutierrez-Posada, Kitsos, Nathan, and Nuccio (2022) demonstrate that creative clusters can have positive economic impacts on local service employment. Penang can leverage this by designing policies that harness the economic potential of creative jobs to benefit surrounding local businesses.

Policy recommendations for Penang should include clear strategic directions, as emphasised by Khoo (2024). This involves operationalising terminologies and aligning creative industry clusters with local nuances.

Integrating culture and creativity across all policy domains will ensure a holistic approach to policy-making. Gabriel (2024) poignantly suggests embracing diversity, reusing heritage buildings, and involving the community in placemaking. Penang can focus on these aspects to foster vibrant, inclusive creative spaces. Additionally, insights from Wu (2022) highlight the importance of Taiwan’s Creative Content Agency in promoting talent and leveraging international marketing strategies which gives productive examples for Penang and Malaysia to emulate. Supporting local talent and enhancing global visibility can strengthen Penang’s creative sector.

By incorporating these lessons, Penang can develop a more effective and supportive policy framework for its creative clusters, fostering a thriving and sustainable creative ecosystem.

Recommendations:

To standardise and boost the economy of creative industry clusters, we propose the following detailed strategy with a focus on multimedia creative industries.

1. Encourage Larger Investments for Future Transformation:

Develop funding programs that support the entire ecosystem of the creative multimedia industry, from education and training to production and distribution. Explore funding options from federal and state governments, as well as private sector partnerships, to ensure comprehensive support for the industry.

Advocate for significant and sustained investments in multimedia creative industry clusters to ensure long-term growth and stability in local economies.

Allocate funding to promising start-ups in the multimedia creative industry.

2. Create Dedicated Spaces for the Creative Multimedia Industries:

Develop spaces for the community such as regular exhibitions, expositions, and festivals to promote creative industry clusters and their outcomes.

3. Collaborate with Partners and Engage with International Audiences:

Build local and global partnerships with educational institutions, private sector companies, and government agencies to leverage resources and expertise.

Attendance and participation in international competitions and festivals to showcase local talent, gain exposure, and attract investment to local multimedia creative industries.

By focusing on these strategic actions, we can create a vibrant and sustainable economy vis-a-vis creative industry clusters.

Promoting Malaysia’s multimedia creative industry clusters will give good returns to Penang in terms of economic gains, employment opportunities, and cultural sustainability. A thriving film industry for instance can significantly boost Malaysia’s economy by creating jobs, enhancing tourism, and fostering related industries such as fashion, music, and technology.

Additionally, films are a powerful medium for cultural expression.

Footnotes

[1] From University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.[2] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development [UNCTAD]. (2024). Creative Economy Outlook 2024. United Nations Publications. Retrieved from https://unctad.org/system/files/officialdocument/ditctsce2024d2_en.pdf

[3] Jawaheer, J., Nur Afiqah A. N., Nasiroh, O., Sharifah A., & Suraya, M. (2020). Reminiscing the legendary P.

Ramlee through data visualization technique. Mathematical Sciences and Informatics Journal, Vol. 1 (2), 59-69 http://www.mijuitmjournal.com

[4] Malaysia country overview. Cultural cities profile East Asia. (2021). https://www.britishcouncil.my/sites/default/files/malaysia_cultural_cities_profile_malaysia.pdf

[5] Khoo, S. L. (2024). Positioning the creative city agenda within urban policy discourse: The Malaysian scenario. Kajian Malaysia 42(1): 71‒95. https://doi.org/10.21315/km2024.42.1.4

[6] Fernandez, A., Lim, S. S., & Pan, Y. C. (2019). The future of creative industries in Penang. Penang Institute Issues: Analyzing Penang, Malaysia, and the Region. https://penanginstitute.org/wpcontent/uploads/2019/02/feb_22_2019_PAL_download.pdf

[7] Barker, T., & Beng, L. Y. (2017). Making creative industries policy: The Malaysian case. Kajian Malaysia, Vol.35, No. 2, 21–37. https://doi.org/10.21315/km2017.35.2.2

[8] Akademi Sains Malaysia [ASM]. (2018). Mega science 3.0: Creative industry sector. Final report. Retrieved

from https://www.akademisains.gov.my/asm-publication/megascience-3-creative-industry-sector/

[9] Rosli S., Borhan, A., Zairul Anuar, M.D., & Sharip Zainal, S.S. (2022). Behind the scenes film industry workers in Sabah: issues, challenges and strategies. Retrieved from https://jurcon.ums.edu.my/ojums/index.php/GA/article/view/4072

[10] Abdul Razak, H.M., & Mohd Syuhaidi, A.B. (2018). Meneroka permasalahan tenaga modal insan dalam industri filem di Malaysia. Forum Komunikasi, Vol. 13 (1)., 41-56.

[11] Khoo S. L. 2024. Positioning the creative city agenda within urban policy discourse: The Malaysian scenario. Kajian Malaysia 42(1): 71‒95. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.21315/km2024.42.1.4

[12] Ibid.

[13] The Sun. (2019). DICE policy to drive Malaysia as a regional digital content hub. https://thesun.my/business/dice-policy-to-drive-malaysia-as-a-regional-digital-content-hub-DE1240731

[14] See Footnote 1.

[15] Lee, YH & Lim, SY (2019). Assessing Malaysia’s creative industry: progress and policies in the case of the film

industry, vol. 12 (2). 224-245. https://doi.org/10.3846/cs.2019.7978

[16] Badrul Hisham, I. (2024). Do Malaysian Films Have a Future? (Penang Monthly, May Issue).

https://penangmonthly.com/article/21132/do-malaysian-films-have-a-future

[17] Ferrarese, M. (2023, 10 March). Michelle Yeoh’s success masks struggle of Malaysian film industry.

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/3/10/michelle-yeohs-success-masks-struggle-of-malaysian-film-

industry

[18] Power, D., & Collins, P. (2021). Peripheral visions: the film and television industry in Galway, Ireland. Industry

and Innovation, Vol. 28 (9) 1150 1174https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2021.1877633© 2021

REFERENCES

Abdul Razak, H.M., & Mohd Syuhaidi, A.B. (2018). Meneroka permasalahan tenaga modal insan dalam industri filem di Malaysia. Forum Komunikasi, Vol. 13 (1), 41-56.

Akademi Sains Malaysia [ASM]. (2018). Mega science 3.0: Creative industry sector. Final report. https://www.akademisains.gov.my/asm-publication/megascience-3-creative-industry-sector/

Baily, M. N., & Montalbano, N. (2018). Clusters and innovation districts: Lessons from the United States Experience. The Brookings Institution: Economic Studies at Brookings, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/es_20180508_bailyclustersandinnovation.pdf

Barker, T., & Beng, L. Y. (2017). Making creative industries policy: The Malaysian case. Kajian Malaysia, Vol. 35 (2), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.21315/km2017.35.2.2

Cunningham, S. & McCutcheon, M. (2020). Australian cultural and creative activity: A population and hotspot analysis- Innovation Precincts in Adelaide. QUT Digital Media Research Centre, December. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/206903/1/73192155.pdf

Fernandez, A., Lim, S. S., & Pan, Y. C. (2019). The future of creative industries in Penang. Penang Institute Issues: Analyzing Penang, Malaysia, and the region, https://penanginstitute.org/publications/issues/the-future-of-creative-industries-in-penang/

Gabriel, I. (2024). Hin Bus Depot: A decade of stimulating creative resurgence in Penang. Penang Monthly, February Issue, 6-11.

Gutierrez-Posada, D., Kitsos, T., Nathan, M., & Nuccio, M. (2022). Creative clusters and creative multipliers: Evidence from UK Cities. Economic Geography, 99(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2022.2094237

Hancock, D., Slee, J., & Wunsch-Vincent, S. (2024). Resurgence of global cinema: 2022 and 2023 witness forceful comeback but still shy of pre-pandemic norms,

https://www.wipo.int/global_innovation_index/en/gii-insights-blog/2024/global-cinema.html#

Jawaheer, J., Nur Afiqah A. N., Nasiroh, O., Sharifah A., & Suraya, M. (2020). Reminiscing the legendary P. Ramlee through data visualisation technique. Mathematical Sciences and Informatics Journal, Vol. 1 (2), 59-69 http://www.mijuitmjournal.com

Khoo, S. L. (2024). Positioning the creative city agenda within urban policy discourse: The Malaysian scenario. Kajian Malaysia. 42(1): 71‒95. https://doi.org/10.21315/km2024.42.1.4

Lee, YH & Lim, SY. (2019). Assessing Malaysia’s creative industry: progress and policies in the case of the film industry Creative Studies. Vol. 12 (2). 224-245. https://doi.org/10.3846/cs.2019.7978

Marnane, K., Saul, K., Luki, M., & Triantis V. (2024). Crafting creative clusters. Urbis, https://urbis.com.au/app/uploads/2024/04/URBIS-Creative-Industries-Thought-Piece-Digital-PDF-1.pdf

Power, D., & Collins, P. (2021). Peripheral visions: the film and television industry in Galway, Ireland. Industry and Innovation, Vol. 28 (9) 1150 – 1174.https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2021.1877633© 2021

Sioson, E. P., & Korwatanasakul, U. (2021). Mapping the readiness of ASEAN’s creative system. The ASEAN, Oct-Nov Issue. 21-25. https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/The-ASEAN-Oct-Nov-2021-Digital-v1.pdf

Syamsul Bahrin, Z., Asmidah, A., Ahmad Hisham, Z.A., & Adzrool Idzwan, I. (2024). A review of policy on creative Industry for sustainable nation: A Malaysian perspective. In book: Computing and Informatics (380-394).

Teoh, S. (2023). The future depends on the creative economy. Penang Monthly, April Issue, 14-18.

The Sun. (2019). DICE policy to drive Malaysia as a regional digital content hub. https://thesun.my/business-news/dice-policy-to-drive-malaysia-as-a-regional-digital-content-hub-DE1240731

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development [UNCTAD]. (2024). Creative Economy Outlook 2024. United Nations Publications, July 11. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ditctsce2024d2_en.pdf

Wu, A. (2022). An Interview with TAICCA on Taiwan’s Cultural and Creative Industries and the Future of Taiwan’s Soft Power. Global Taiwan Institute, June 1. https://globaltaiwan.org/2022/06/an-interview-with-taicca-on-taiwans-cultural-and-creative-industries-and-the-future-of-taiwans-soft-power/

You might also like:

![Key Changes to Development Expenditure in Malaysia’s Budget 2019]()

Key Changes to Development Expenditure in Malaysia’s Budget 2019

![The Value of Private Member’s Bills in Parliament: A Process Comparison between Malaysia and the Uni...]()

The Value of Private Member’s Bills in Parliament: A Process Comparison between Malaysia and the Uni...

![Tighter Collaboration Needed in Penang’s Skills Development Infrastructure]()

Tighter Collaboration Needed in Penang’s Skills Development Infrastructure

![The Policing and Politics of the Malay Language]()

The Policing and Politics of the Malay Language

![Sustainable Strategies based on Penang Infrastructure Corporation's Projects]()

Sustainable Strategies based on Penang Infrastructure Corporation's Projects