Dr. Beh May Ting (Programme Coordinator & Senior Analyst, History & Regional Studies Programme) |

Posted onExecutive Summary

Malaysia’s plan to ban social media for teenagers under 16, set to take effect in 2026, is a bold but blunt instrument. While it signals strong political will to protect children from online harms, its rigidity risks overlooking the nuanced realities of digital childhoods.

While high connectivity has expanded access to learning and innovation, the absence of structured digital boundaries, particularly for children, has led to concerning patterns of overexposure. Mounting evidence links excessive screen time to cognitive delays, emotional dysregulation, physical inactivity, and sleep disturbances. Left unaddressed, these trends risk eroding the foundations of Malaysia’s future human capital.

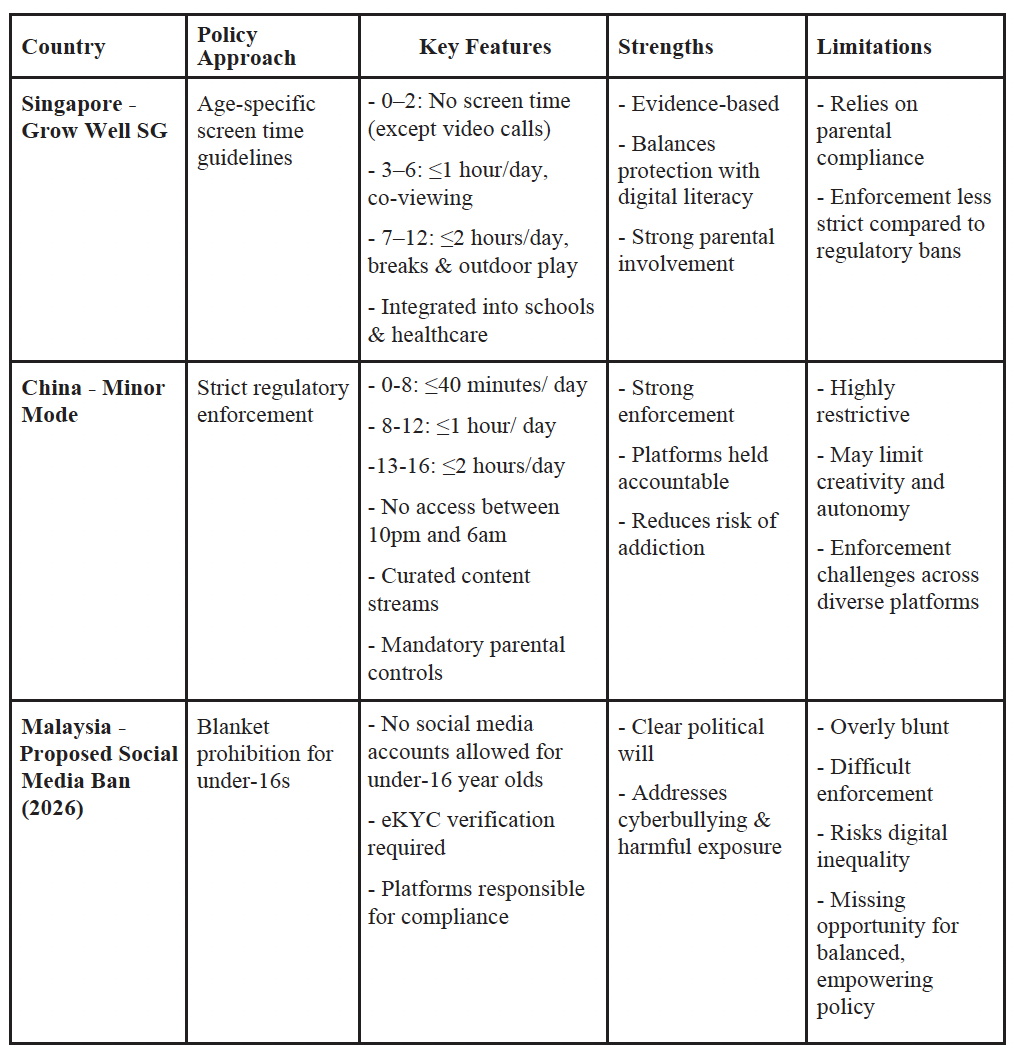

This paper compares child screen time policies adopted in Singapore and China, and proposes that age-specific screen time policies, when embedded in school systems and supported by parental education, yield measurable improvements in child wellbeing. This model underscores the value of proactive governance and cross-sector collaboration.

With its progressive policy culture and community engagement, Penang can pioneer the Penang Child Digital Wellbeing Guideline to foster healthier, more resilient digital childhoods.

Towards a Healthier Digital Childhood: Guidelines on Screen Use for Children

By Dr. Beh May Ting (Programme Coordinator & Senior Analyst, History & Regional Studies Programme)

Introduction

In an era defined by digital acceleration, the question is no longer whether children will engage with screens, but how, and under what conditions. As digital technologies permeate homes, classrooms, and public spaces, the formative years of childhood are increasingly shaped by screen-based interactions. While these tools offer unprecedented access to information and learning, their unregulated use poses complex challenges to child development, public health, and long-term societal resilience.

Malaysia stands at a critical juncture in shaping the digital habits of its youngest citizens. This policy paper proposes evidence-based, age-specific guidelines supported by public health initiatives, parental education, and institutional collaboration. The aim is to cultivate a balanced digital environment that enhances learning and creativity while safeguarding children’s wellbeing.

By introducing a coherent, evidence-based framework, Penang can help parents, educators, and policymakers make informed decisions on digital engagement. This initiative aligns with the state’s commitment to build a family-focused and future-ready society, and could serve as a model for national policy on child digital wellbeing.

Health and Developmental Risks of Excessive Screen Time

Excessive screen time during early childhood has been increasingly linked to a range of cognitive, physical, and emotional health concerns. A study by the National University of Singapore (NUS) has revealed that infants exposed to high levels of screen time exhibited differences in brain function that persist beyond eight years of age. These children show increased low-frequency brain waves, a pattern associated with reduced cognitive alertness and impaired executive function (Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, 2023). The GUSTO (Growing Up in Singapore Towards Healthy Outcomes) study further found that toddlers under two years old in Singapore are exposed to an average of two hours of screen time daily, contributing to sedentary habits and poorer mental health outcomes later in life (CHILD, 2021).

Physically, prolonged screen exposure is associated with digital eye strain, poor posture, and reduced physical activity. According to The Children’s Trust, symptoms such as dry eyes, headaches, and blurry vision are common among children who spend extended periods on screens. Additionally, screen time often displaces outdoor play, increasing the risk of childhood obesity and related conditions such as high blood pressure and insulin resistance (Satnarine & Rosenbaum, 2025).

Sleep disruption is another major concern. Blue light emitted from screens suppresses melatonin production, delaying sleep onset and reducing sleep quality. This is particularly problematic when children use screens close to bedtime, a habit that has become more prevalent.

Malaysia’s Social Media Ban

Malaysia recently announced that children under 16 will be prohibited from signing up for social media accounts starting in 2026, with platforms required to implement electronic know-your-customer verifications (eKYC) to enforce the rule. The policy is motivated by legitimate concerns such as cyberbullying, online scams, and exposure to harmful content. However, its design raises several critical issues.

Overly Restrictive Approach

A blanket ban on social media for teenagers runs the risk of cutting young people off from valuable digital experiences that are increasingly integral to modern life. Social platforms are not only spaces for entertainment but also serve as hubs for educational communities, creative expression, and civic engagement. Teenagers often use these platforms to collaborate on school projects, share artistic work, or participate in discussions that foster critical thinking and social awareness. By imposing a total prohibition, Malaysia may inadvertently stifle opportunities for young people to develop digital literacy and the skills necessary to navigate online environments responsibly.

In contrast, cities like Singapore and London have adopted more nuanced strategies that balance protection with empowerment. Rather than outright bans, these jurisdictions emphasize structured guidelines, age-appropriate content moderation, and strong parental involvement. Singapore’s national health framework, for instance, encourages co-viewing and sets clear screen time limits, while London integrates digital literacy into school curricula to ensure children learn how to critically assess online information (Polizzi, 2020).

The UK Online Safety Act (2023) strengthens child protection online by requiring platforms to safeguard young users from harmful content and misinformation. This regulatory framework complements the national curriculum’s emphasis on digital literacy, which equips children with the skills to critically assess online information and resist manipulation. Together, education and regulation form a dual strategy that empowers children to navigate digital spaces responsibly while ensuring platforms are held accountable for creating safer online environments.

These models demonstrate that regulation can be both protective and enabling, arming children with the tools to thrive in a digital society while safeguarding their wellbeing. Malaysia’s current plan is no doubt well-intentioned, but it could benefit from adopting such layered approaches that recognize the dual nature of digital platforms as both potential risks and essential resources for growth.

Enforcement Challenges

Enforcement of Malaysia’s proposed social media ban for teenagers faces significant challenges, particularly because it relies heavily on electronic identity verification (eKYC). While eKYC is designed to ensure that users are accurately identified before gaining access to platforms, the responsibility for implementation falls largely on global technology companies such as TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube. These platforms operate across multiple jurisdictions, each with its own regulatory frameworks, making consistent enforcement difficult. Moreover, the sheer scale of these platforms means that monitoring and verifying every account is a complex and resource-intensive task.

Even if eKYC is successfully implemented, teenagers are adept at finding ways to bypass restrictions. They could use virtual private networks (VPNs) to mask their location and access restricted content, and the creation of fake accounts with falsified information is a common workaround. Shared devices, such as family computers or tablets, also present loopholes, as younger users can access accounts created by older siblings or parents. These circumvention strategies undermine the effectiveness of the policy, raising questions about whether a blanket ban can realistically achieve its intended goals.

The enforcement challenge highlights the need for a more layered approach. Rather than relying solely on technological barriers, Malaysia could strengthen parental involvement, promote digital literacy, and integrate screen time education into schools. Such measures would not only make enforcement more practical but also empower children to develop healthier digital habits, reducing reliance on punitive restrictions that are difficult to sustain in practice.

Missed Opportunity for Balanced Policy

Malaysia’s proposed blanket ban on social media for teenagers represents a missed opportunity to craft a more balanced and sustainable policy. While the intention to protect children from online harms is commendable, prohibition alone does not address the broader developmental needs of young people growing up in a digital society. A more constructive approach would be to introduce age-specific screen-time guidelines supported by school-level enforcement and parental involvement. This would allow children to benefit from the positive aspects of digital engagement, such as educational communities, creative expression, and social participation, while minimizing exposure to harmful or excessive use.

China’s Minor Mode, introduced in 2025, represents one of the most ambitious child-protection frameworks in the digital sphere. It imposes strict age-based screen time limits, i.e. 40 minutes for children under 8, one hour for those aged 8–12, and two hours for teenagers up to 16, and banning access between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. Beyond time restrictions, the regulation requires platforms to provide curated, age-appropriate content and equips parents with monitoring tools to oversee usage. Major smartphone manufacturers such as Huawei, Oppo, and Xiaomi have integrated Minor Mode directly into their devices, ensuring nationwide enforcement under the oversight of the Cyberspace Administration of China. While praised for its scope and enforcement, critics see it as overly paternalistic, restricting autonomy and creativity, and note that teenagers often bypass controls (Craven, 2024). Ultimately, Minor Mode reflects China’s protection-first governance model, combining time limits, curated content, and parental oversight to create a safer, more moderated digital environment that still acknowledges the importance of digital literacy for education and future employment.

Singapore’s digital guidelines for children are embedded within the Grow Well SG initiative, jointly developed by the Ministry of Health (MOH), the Ministry of Education (MOE), and the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF). These guidelines recommend no screen time for children under 2, less than one hour daily for ages 2–5, and no more than two hours daily for ages 6–12, while encouraging interactive, educational use over passive viewing. They also stress the importance of screen-free routines during meals, bedtime, and family bonding, and provide parents with tools to co-create healthy practices. By embedding these recommendations into schools, healthcare, and community programmes, Singapore adopts a policy-driven, holistic approach that balances protection with empowerment, ensuring children learn to manage digital tools responsibly rather than excluding them from their use entirely.

Malaysia could benefit from adopting similar measures; this would help ensure that its policies are not only protective but also empowering. By focusing on balance rather than restriction, Malaysia has the opportunity to cultivate a generation of digitally literate, emotionally resilient, and socially responsible young people who are prepared to thrive in an increasingly connected world.

Comparative Approaches to Child Digital Wellbeing

Policy Recommendations

1. Age-Specific Screen Time Regulations

To safeguard child wellbeing while fostering responsible digital use, it is recommended that clear daily screen time limits be established: no screen exposure for children under two years old, a maximum of one hour for those aged three to six, and no more than two hours for children aged seven to twelve. These guidelines should be systematically integrated into schools, pediatric health check-ups, and community programmes to ensure consistent reinforcement across educational,

healthcare, and social settings.

In addition, parents should be equipped with practical tools such as co-viewing strategies and the promotion of screen-free routines to support healthy family practices and strengthen children’s ability

to engage with digital media responsibly.

2. School-Level Digital Wellbeing Integration

To strengthen child digital wellbeing, it is recommended that digital literacy and wellbeing modules be mandated in primary school curricula, ensuring that children learn responsible online engagement from an early age. Schools should also introduce designated “screen-free hours” to encourage outdoor play, creative activities, and social interaction beyond digital devices.

In addition, teachers must be trained to identify early signs of screen overuse and refer cases for appropriate health or counseling support, creating an early intervention safety net. Finally, nurseries and kindergartens should be prohibited from using digital screens during childcare hours, with institutions found in violation facing non-renewal of their operating licenses. This integrated policy framework combines education, preventive measures, and enforcement to promote healthier, more balanced digital habits among children.

3. Community and Family Support Systems

To promote equitable and sustainable child digital wellbeing, statewide awareness campaigns targeting parents and caregivers are recommended, which highlight the risks of unregulated screen use and the importance of healthy digital habits. These efforts should be complemented by community-based digital literacy workshops to ensure that families across all socioeconomic groups have access to practical guidance and resources.

In addition, healthcare providers should incorporate digital wellbeing assessments into routine child health screenings, creating an integrated system of early detection and support. Together, these measures establish a comprehensive policy framework that combines public education, community empowerment, and healthcare intervention to safeguard children’s digital health.

Conclusion

Malaysia’s proposed ban on social media for teenagers under 16 reflects a genuine concern for child wellbeing, but its bluntness risks unintended consequences. In contrast, Singapore’s Grow Well SG initiative demonstrates that regulation can be both protective and empowering. By combining age-specific screen time guidelines with parental involvement and school-level integration, Singapore has created a framework that safeguards children while equipping them with the digital literacy

essential for modern life.

By choosing balance over prohibition, Penang can set a national precedent, aligning with the Penang2030 vision of a “Family-Focused, Green and Smart State.” More importantly, it can demonstrate that child digital wellbeing is best achieved not through bans, but through thoughtful, layered governance that protects, empowers, and prepares the next generation for a connected future.

References

CHILD. (2021, July). Impact of screen viewing during early childhood on cognitive development. Centre for Holistic Initiatives for Learning & Development. Available at https://thechild.sg/wp-content/uploads/sites/25/2021/07/EI_002_CHILD_Impact-of-Screen-Viewing-on-Cognitive-Development_For-Circulation-digital.pdf

Craven, T. (2024). Kids, No Phones at the Dinner Table: Analyzing the People’s Republic of China’s Proposed “Minor Mode” Regulation and an International Right to the Internet. Chicago Journal of International Law, 25(1), 219–250. Available at https://cjil.uchicago.edu/print-archive/kids-no-phones-dinner-table-analyzing-peoples-republic-chinas-proposed-minor-mode

Polizzi, G. (2020). Digital literacy and the national curriculum for England: Learning from how the experts engage with and evaluate online content. Computers & Education, 152, 103859. Available at https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/103538/1/DIGITAL_LITERACY.pdf

Satnarine, T, & Rosembaum, T. (2025). Health Impacts of Excessive Screen Time. The Children’s Trust. Available at https://www.thechildrenstrust.org/news/parenting-our-children/health-impacts-of-excessive-screen-time/

Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine. (2023, 31 January). Study: Infants exposed to excessive screen time show differences in brain function beyond eight years of age. National University of Singapore. Available at https://medicine.nus.edu.sg/news/study-infants-exposed-to-excessive-screen-time-show-differences-in-brain-function-beyond-eight-years-of-age/

You might also like:

![Obesity in Malaysia: Unhealthy Eating is as Harmful as Smoking]()

Obesity in Malaysia: Unhealthy Eating is as Harmful as Smoking

![Tracking Malaysia’s Development Expenditure in Federal Budgets from 2004 to 2018]()

Tracking Malaysia’s Development Expenditure in Federal Budgets from 2004 to 2018

![The Digital Free Trade Zone – A Path to Inclusive Growth?]()

The Digital Free Trade Zone – A Path to Inclusive Growth?

![Helping SMEs Rise to Challenges Posed by the Covid-19 Pandemic]()

Helping SMEs Rise to Challenges Posed by the Covid-19 Pandemic

![Malaysia in the ASEAN Chair 2025: Policy Recommendations from Penang Institute]()

Malaysia in the ASEAN Chair 2025: Policy Recommendations from Penang Institute