Executive Summary

- Malaysia and Indonesia have the highest proportion of obese and overweight citizens in ASEAN, and unsurprisingly, both countries show the highest overall costs of obesity as a percentage of healthcare spending in the region

- Obesity reduces productivity significantly and has a direct impact on the country’s GDP performance

- Policy interventions are available, but lack strict enforcement by the governments and authorities

- Examples from other countries show that interventions that target individual food intake, physical exercise, food labelling and taxation hold great potential in tackling obesity in Malaysia

- In the case of Malaysia, such interventions are available at both the federal and state levels

Introduction

Obesity is influenced by factors such as rising income, urbanisation, shifting lifestyles and genetic aspects. It is a growing concern in Malaysia as diseases such as Type 2 diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, stroke and chronic diseases are reaching worrying levels. Recently, Malaysia’s Health Minister Subramaniam Sathasivam warned that the country is facing an obesity epidemic, and just over half of the population is either overweight or obese.[1] By comparison, 20 years ago, only 4% of Malaysians were considered obese. According to the latest estimates from the World Health Organisation (WHO), almost 14% of the country’s citizens fall under the ‘obese’ category. A further 40% are overweight. In the last 45 years, fat and sugar intake has increased by 80% and 33% respectively.

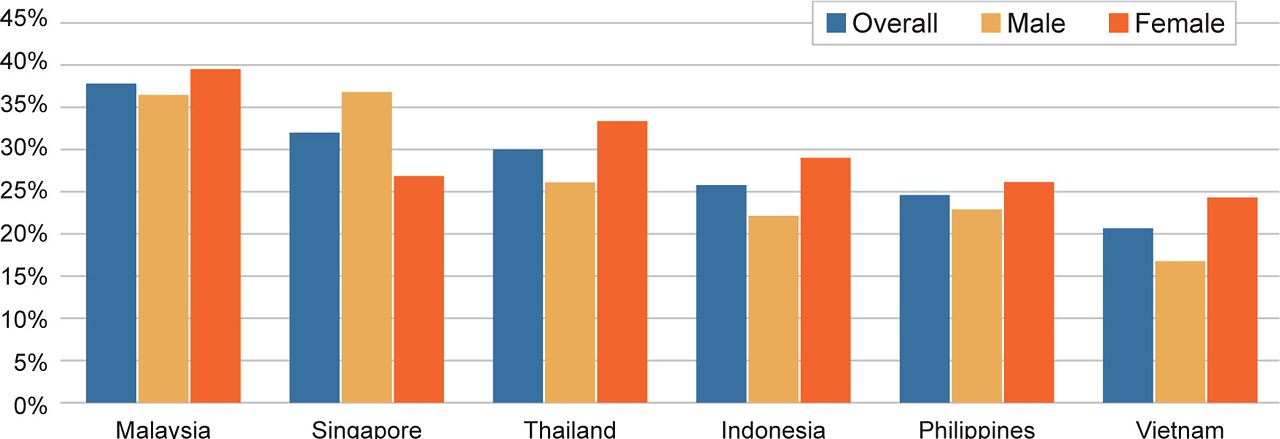

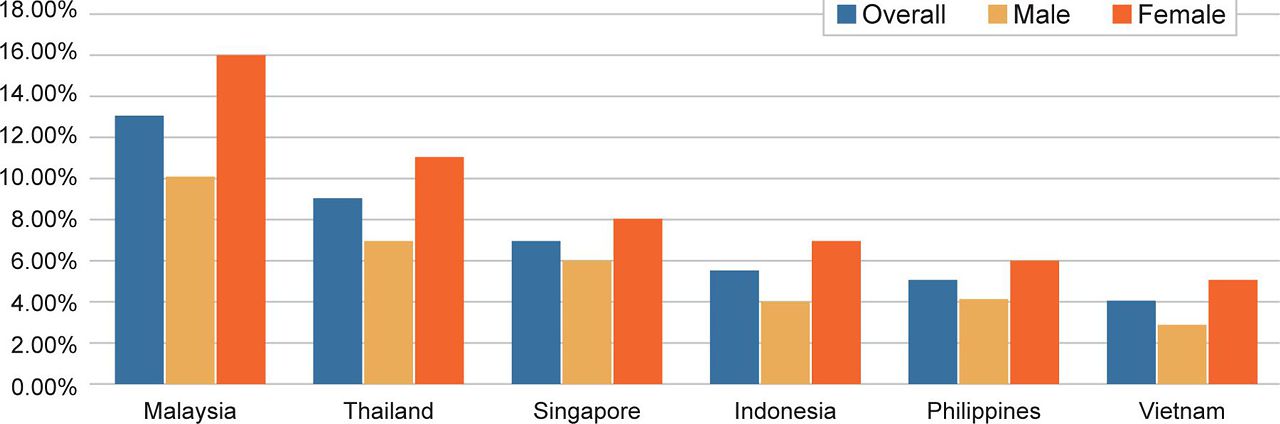

The Body Mass Index (BMI) is generally used to classify an adult population as underweight (BMI <=18.5), overweight (BMI >=25.0) or obese (BMI >=30.0). The normal BMI range lies between 18.5 and 24.99. The BMI is calculated by a person’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of his or her height in metres (kg/m2). BMI values are independent of age or gender. As shown in Figures 1 and 2, Malaysia has the most overweight and obese population among ASEAN countries.

Figure 1: Percentage of overweight population with BMI>=25, agestandardised adjusted estimates, adults

Figure 2: Percentage of obesity prevalence population with BMI>=30, agestandardised adjusted estimates, adults

Impact and economic costs

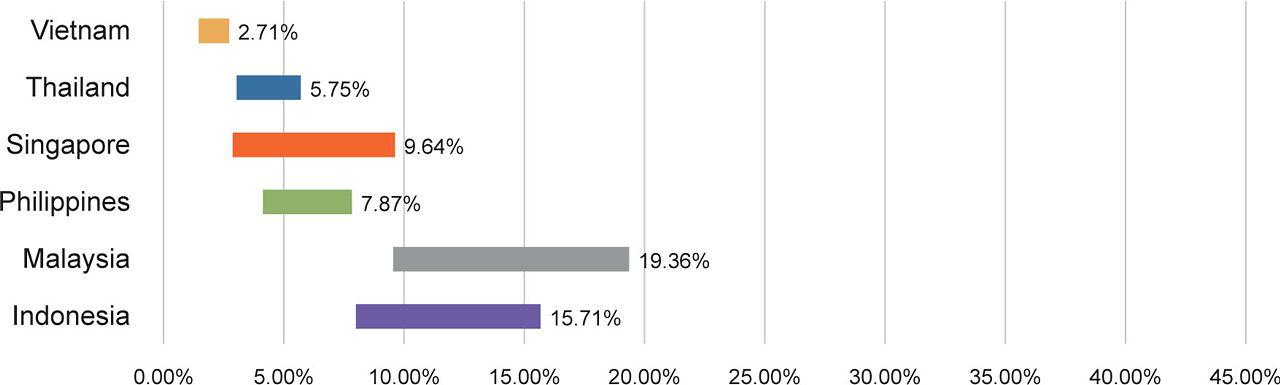

As illustrated in Figure 3, Malaysia also suffers the highest overall cost for obesity as a percentage of the country’s healthcare spending, reaching an alarming 10-20% of the country’s healthcare expenditure. Among other ASEAN countries, Indonesia ranks second with costs at 8-16% of healthcare spending, while Singapore comes third, with costs at 3-10%. The table also shows that obesity is both a problem in developed, as well as middle-income and developing countries in the region.

Figure 3: Total cost of obesity as a percentage of healthcare spending[2]

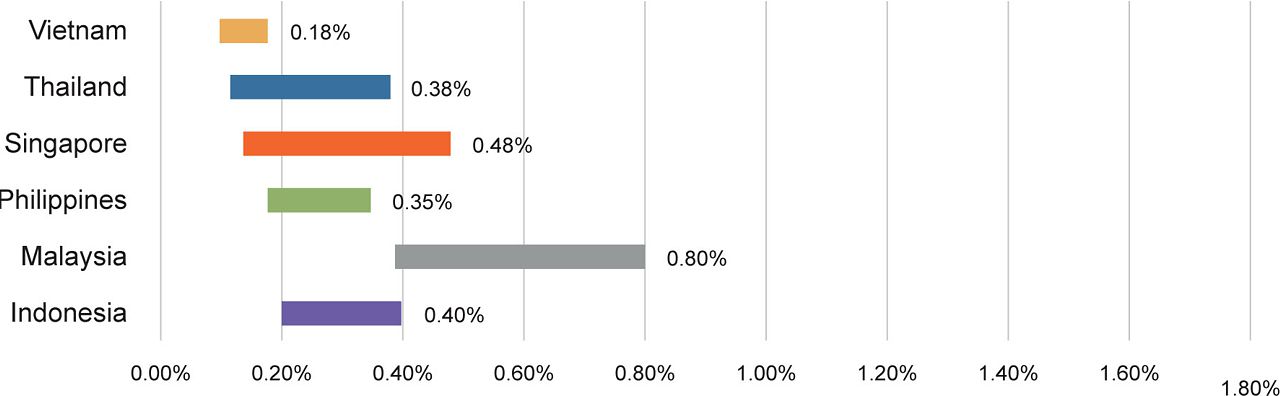

Obesity also has a direct impact on the country’s GDP performance. As shown in Figure 4, Malaysia’s total cost for obesity as a percentage of nominal GDP ranks top at a range between 0.4% and 0.8%, far ahead of all other countries in ASEAN. A recent study estimates that worldwide GDP losses both from direct and indirect costs of diabetes from 2011 to 2030 will total US$1.7tril, comprising US$900bil for high-income countries and US$800bil for low- and middle-income countries.[3]

Figure 4: Total cost for obesity as a percentage of nominal GDP[4]

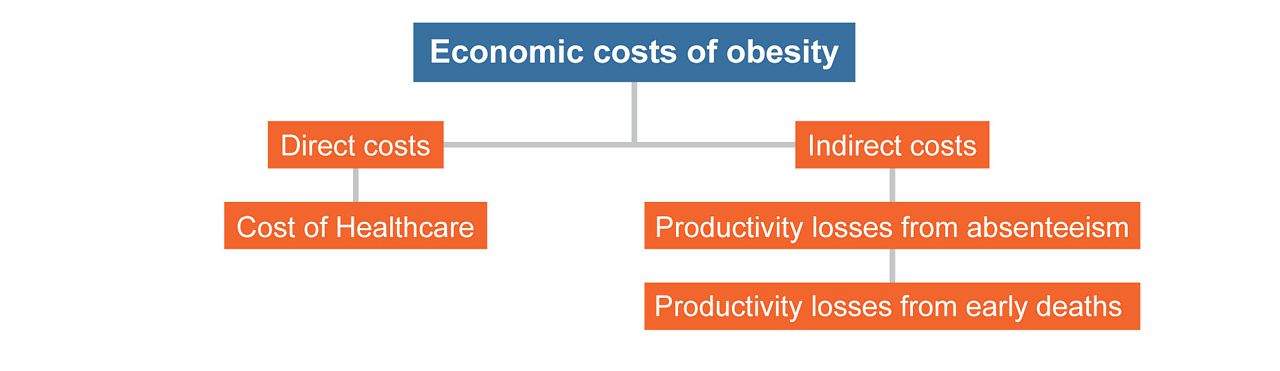

Costs for obesity can be classified into direct and indirect costs. Both are substantial for the public healthcare system, including treatment costs, lost economic output and the loss of years of productive life due to obesity-related mortality. Direct costs involve private and public specialist treatments, as well as other medical consultation fees. Indirect costs are productivity losses due to greater frequency of illness, or dropping out of the workforce by reason of early death or low average retirement ages.

Figure 5: Economic costs of obesity

A study conducted by “The Economist” shows that the total cost of obesity in Malaysia lies between US$4-7bil (RM17-30bil).[5] This is equivalent to about 2% of the country’s total GDP.

Obesity interventions

Drawing up effective interventions and policies to combat the problem, however, is challenging. Obesity in Malaysia has genetic and behavioural underpinnings and policies need to be weighed against political practicability.

Generally speaking, obesity is a result of excessive and inadequate food intake, combined with the lack of physical activity and genetic susceptibility. To help people maintain a healthy weight, the WHO has come up with some simple guidelines. These include the advice that a person’s total fat intake should not exceed 30% of the total energy intake; that fat consumption should be shifted from saturated to unsaturated fats; and that industrial trans fats should be eliminated from individual diets. The WHO also recommends reducing the intake of free sugars to less than 10% of total energy intake. Aiming for less than 5% is optimal. Additionally, individuals should perform at least 150 minutes of physical activity per week.

The chances of developing obesity are low if these guidelines are followed. However, governments have been largely unsuccessful in combating obesity in recent decades, with studies showing that the proportion of overweight adults globally increased from 28.8% to 36.9% between 1980 and 2013, and there has also been a substantial increase in overweight and obese children in both developed and developing countries.

Table 1: Interventions showing the greatest promise [7]

Table 1 shows a list of interventions that are considered to hold the greatest potential in battling obesity. Most promising are interventions that target food intake. Based on global evidence, reducing portion sizes, taxation of specific food types and the implementation of certain school and workplace policies have shown great success. Physical activity interventions have great potential as well, especially when combined with a healthy diet.

There are three types of interventions to consider when fighting obesity, namely (1) physiological interventions; (2) physical activities; and (3) psychology and behaviour.

Physiological interventions include surgical procedures and anti-obesity medications. Generally, surgery is a safe and effective option that leads to weight loss in the short term. It quickly improves life and can put Type 2 diabetes into remission. However, since surgeries are expensive and require technical expertise, only morbidly obese patients should consider them. Surgery as an intervention therefore has little impact at the general level.

Among adults and children, physical activities are an effective method for reducing overweight and obesity, especially when combined with a healthy diet. These are important interventions given the fact that increasing urbanisation and rising income have perpetuated a sedentary lifestyle in Malaysia. The government has introduced a media-friendly physical activity campaign called “10,000 Steps A Day”. Other countries in the region have explored similar campaigns, such as the “Walk for Nutrition” in the Philippines or Singapore’s “National Steps Challenge”. In Indonesia, Jakarta implements a car-free Sunday zone so people can use the freed public space for physical activities. However, the effectiveness of such campaigns remains to be seen.

Singapore, with its “Trim and Fit” programme, which includes physical activity regimes for overweight children, is one of the few countries that has actually implemented a structured evaluation policy for physical exercise. It successfully reduced obesity among 11-12 year olds from 16.6% in 1992 to 14.6% in 2000, and in the 15-16 age group cohort, from 15.5% to 13.1%.[8]

Other physical activity programmes in the region involve efforts to restructure public spaces to encourage the uptake of physical exercise. Urban planning is considered crucial to anti-obesity policies. Congested cities in the region do lack open spaces, and the hot and humid climate discourages people from being physically active outdoors. Air-conditioned gymnasiums are available only to the affluent classes.

The most common cause of obesity is the consumption of unhealthy foods and the failure to perform sufficient exercise. Routines formed in childhood, lack of information or education, and behavioural inclinations are all factors that inform personal dietary choices and lifestyle behaviours. To counteract this, interventions that encourage behavioural changes, such as advertisements and educational campaigns may be useful.

Policy recommendations

Awareness campaigns

As early as 1997, the Malaysian Ministry of Health had started taking steps to tackle obesity in the population by launching a healthy eating campaign, followed by a “Less is More” campaign in 1998 to reduce sugar intake.

Singapore has also undertaken several psychology-based campaigns, often leveraging on competitive or prize-giving incentives. Starting in 2000, the Health Promotion Board introduced the Championing Efforts for Improving School Health (CHERISH) Award in schools to encourage schools to set up comprehensive health promotion programmes for staff and students. In 2015, the country’s “Life’s Sweeter with Less Sugar” campaign encouraged people to choose unsweetened drinks by offering ‘scratch and win’ cards upon purchase of relevant products.

Another approach is to publish nutritional guidelines that advise consumers on how various ingredients affect their weight. Tackling unhealthy eating routines in childhood through school-based educational campaigns may offset full life-cycle obesity that would incur considerably more expensive health outcomes for the individual and society in the long run.

Advertisements

Advertisement restrictions are another important intervention measure. Nowadays, people are increasingly confronted by media messages promoting nutrient-poor food and beverages. Such is definitely the case in Malaysia. During school holidays for example, TV advertisements for unhealthy foods are rampantly obvious.

To name a few further policy examples that may be relevant to Malaysia, the governments of Norway, Sweden and the Canadian state of Quebec have all banned advertisements targeting children aged 12 years and under. Since January 2016, Taiwan’s Food and Drug Administration has restricted commercials promoting unhealthy foods from broadcasting on children’s channels between 5pm and 9pm, and companies promoting unhealthy meals aimed at children are prohibited from offering free toys. Restrictions are also placed on high-fat and high-calorie foods.

Singapore’s Advertising Standards Authority has announced that adverts “should not actively encourage children to eat excessively throughout the day, or to replace main meals with confectionery or snack foods.” [9] However, these regulations do not cover social media platforms and applications, or international websites. A new advertising code took effect in January 2015 to reduce children’s exposure to advertisements for food and beverages high in fat, sugar and salt.

In 2010, South Korea implemented efficient controls on TV advertisements for energy-dense and nutrient poor (EDNP) foods, targeting the hours that children were likely to watch the TV. In Indonesia, advertisements are not permitted to be broadcasted to children under the age of five, unless the product is especially designed for children of that age category.

The fiscal approach

Governments around the world have been exploring the taxation of unhealthy foods to discourage consumption. For example, Indonesia, India and the Philippines have considered the implementation of sugar taxes. In December 2015, an Indian government committee recommended a 40% levy on high-sugar drinks. However, this recommendation was not turned into a policy initiative. Other schemes are progressing in the Philippines where the government is set to introduce a 10% tax on all sugar-sweetened drinks. In April 2016, a proposal was made in Thailand to tax packaged drinks according to sugar content. This would increase prices for these products by up to 20%. Lawmakers in Vietnam had debated a proposed 10% tax on soft drinks in 2014, but this initiative has since been cancelled.

Food labelling

Food labelling has been practiced across ASEAN countries in different ways. In Malaysia and Indonesia, nutrition labelling is required, but other ASEAN countries like Singapore, Thailand and the Philippines maintain a voluntary practice. To be most effective, food labels need to be kept simple and worded in a manner that is easy for consumers to understand.

Food “zoning”

Restricting the availability of unhealthy foods is another promising method. The more inconvenient it is to obtain unhealthy food, the less likely people are to consume them. In January 2012, Malaysia’s Ministries of Education and Health announced new guidelines for food and beverages sold in school canteens, such as the advice to display calorie contents. However, no penalties have been imposed on canteen operators who fail to act accordingly.

Conclusion

Effective interventions are available to Malaysian authorities to encourage the adoption of low-calorie, low-fat and low-carbohydrate diets. These include clearer and simpler food labelling, restricted access to vending machines, and portion-size reductions in schools. Additionally, greater collaboration between the government and the food industry on product innovation, as well as developing best-practice codes of conduct for food and beverage marketing would be helpful. Physical exercise is a key factor in tackling obesity.

In summary, several promising pathways have been identified which can be implemented by

authorities at the federal or state level:

- Interventions that target food intake are promising at the individual and population level

- Physical exercise plays an important role in preventing and reducing obesity. Authorities

should work to increase access for the public to facilities and public spaces where such

activities can be carried out - Simpler food labelling can have a significant impact by helping consumers make informed

choices - The private sector and food industry can also play a constructive role in designing new food

products with lower sugar and fat content - Child-focused obesity measures are most important, as childhood obesity is hard to reverse

and can lead to chronic illnesses later in life. Options include restricting the availability of

higher fat or high-sugar foods in schools. Besides this, physical education must become an

essential and central part of school curricula

[1] https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2016/04/02/putrajaya-tops-obese-list-obesity-on-the-rise-worldwide-it-has-highest-rate-of-overweight-people-in/

[2] Tackling obesity in ASEAN, The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited, 2017, p. 5

[3] Bloom DE, Cafiero ET, Jané-Llopis E, Abrahams-Gessel S, Bloom LR, Fathima S, et al. The global economic burden of

noncommunicable diseases (Working Paper Series). Geneva: Harvard School of Public Health and World Economic

Forum; 2011.

[4] Tackling obesity in ASEAN, The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited; 2017, p. 5

[5] Tackling obesity in ASEAN, The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited; 2017, p. 28

[6] http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/guidelines/sugar_intake_information_note_en.pdf

[7] Tackling obesity in ASEAN, The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited; 2017, p. 32

[8] http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/a-more-holistic-approach-to-a-childs-health-and-fitness

[9] https://www.hpb.gov.sg/article/public-consultation-on-the-proposed-strengthening-of-food-advertising-guidelines-for-children

Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng Editorial Team: Regina Hoo, Lim Su Lin, Nur Fitriah, Ong Wooi Leng

You might also like:

The Covid-19 Disruption Highlights the Neglected Nature of Arts and Culture Sector in Malaysia

Developing the Halal Industry in Penang: An Overview of Policy Issues and Some Possible Solutions

Persevering towards Recovery for Penang’s Tourism Industry

ESG Disclosures among Public-listed Companies Based in Penang

Unleashing Potential: Policy Insights for Malaysia’s Creative Industries