Executive Summary

- A reform of the process of Private Member’s Bills (PMBs) is needed to strengthen the legislative role of MPs in Parliament, and to reduce the overwhelming influence the Malaysian government currently has over Parliament

- MP Hadi Awang’s motion to amend the Syariah Courts (Criminal Jurisdiction) Act 1965 was expedited in 2016. This implies that Malaysia’s PMB process is not independent of government control

- In contrast, PMBs in the UK are allocated time and space for debate, and for consolidating the fact that the power of motioning for laws does not rest solely on the government

- A PMB also highlights social issues by compelling both the public and the government to act for the betterment of citizens

- Parliament is the sole platform for legislation, hence all MPs must be given equal opportunity to legislate regardless of their political leanings

Introduction

Parliament is by far the only political institution where Members of Parliament (MPs) scrutinise the work of the government, debate on issues, check to approve or disapprove government budgets; and rather crucially, draft, discuss and submit bills that, when accepted and passed in Parliament, becomes in due course the law of the land.

Malaysia’s Parliament has however a rather lengthy history of being under the power of the Executive branch of the government. In fact, it has acquired a notorious reputation of being a rubber-stamping assembly of elected MPs.

Acknowledging the limitations on Parliament’s role and power, the Pakatan Harapan (PH) government vowed to “restore” the dignity of the legislature through a number of reforms proposed in its manifesto such as the re-introduction of the Parliamentary Services Act 1963, the recognition of the role and status of opposition leaders in Parliament and the securing of funding grants for MPs.

These reforms ought to be welcomed, but if they are implemented in a situation where there is failure to recognise and overcome deficiencies in ensuring the independence of Parliament’s legislative power, then the long-standing perception of Parliament as an extended arm of the government will not be remedied.

Instead, reforms of the process for Private Member’s Bills[1] (PMBs), for example, would strengthen the legislative branch. At present, flaws in Malaysia’s parliamentary democracy is owed to the fact that the ability to legislate rests primarily with the government’s frontbenchers, and not the backbenchers comprising MPs from all political parties and interests. Consequently, the MPs’ role as legislators has been largely emasculated and predicated on government approval.

Malaysia’s Case: Government-Led Private Member’s Motions

PMBs are generally defined as bills introduced by MPs, from either the ruling or the opposition parties. If there is enough support from MPs, a PMB is accepted, passed and submitted to become an Act. Secondly, a PMB functions by increasing the publicity around the subject, and hopefully influencing the government’s stance on the said issue.

One of the main reasons for Parliament’s dependency on the government is its inability to allocate sufficient space and time for PMBs to be tabled well in parliamentary sittings. The current Standing Order 15 (1) states that government business will always take precedence over Private Member items on the Order Paper in any parliamentary session in Malaysia, be it in filing motions for policy discussion or in introducing bills to enhance the welfare of citizens. The Private Member’s motion or bill is often postponed to another day as there is often not enough time for a tabling and discussion of the bill. In addition, the government may obstruct any Private Member’s business by populating the sitting via the Order Paper, e.g. by adding their own government bills or motions.

The government’s support is very much needed for a Private Member’s business to be allocated sufficient space and time at each parliament sitting.

A case in point is the parliament sitting of May 26, 2016 when Madam Azalina Othman, then acting Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department, expedited MP Hadi Awang’s motion to amend the Syariah Courts (Criminal Jurisdiction) Act 1965, moving it from item no. 15 – the last item in the queue – to no. 1 on the Order Paper, bypassing four government bills, one government motion and nine Private Member’s motions.

By invoking Standing Order 14 (2), a minister can move a motion to proceed before any business of the day, outside of the stipulated agenda. In this case, the Private Member’s motion was successfully tabled in Parliament to be subsequently read out by the proposer of the bill, under the approval of the government as represented by the minister.

The above mentioned example was largely secured through the “blessings” and actions of the government; and this no doubt highlights a clear flaw. The control over the order of the day within Parliament is managed by the government; and more worryingly, it has the power to disregard any Private Member’s motions or bills, choosing instead to decide which business lies suitably within and is aligned to the government’s agenda at each parliament sitting.

Similarly, Malaysia’s Parliament is incapable of facilitating the passing of a PMB without it

first becoming a government bill. According to Standing Order 49, any Private Member desiring to introduce a bill shall do so in the form of a motion, which will then be presented and debated in Parliament. The bill is deemed to have been read for the first time once Parliament has debated and accepted the motion.

From this stage onward, no further action will be taken by the MP whose bill it is which is tabled. Under Standing Order 49 (4), the bill shall stand referred without discussion to the Minister concerned with the subjects or functions to which the bill relates or, if there is no such Minister, then to such other Minister or member as Tuan Yang di-Pertua may nominate; and no further proceedings shall be taken upon such bill until the Minister or member to whom it has been referred has reported to the House thereon.

The PMB will only become a government bill if the Minister decides to follow up; or if no further action is taken, the bill is effectively terminated. It is important to note that once the motion of introducing a PMB has been accepted, there is nothing the MP who first raised the motion can do to affect the content or the progression of the bill. The legislating power once again falls to the government.

PMBs exist to safeguard the legislative right of MPs as conferred on them by their electorate, and to ensure the power of law-making is not monopolised by the government. Subjugating the PMB to the control of the Executive branch of government undermines the MPs’ role in making and amending laws and thus, reduces Parliament into an adjunct of the Executive branch.

Private Member’s Bills in the UK

The use of PMBs is more widely recognised in other countries; there are rules and regulations enacted to ensure the legislative rights of non-government MPs[2] are protected. The UK Parliament, for example, has an established tradition of raising PMBs to increase publicity and awareness on a particular issue, as well as to push them through as legislations.

A notable achievement is the introduction of the PMB by Labour MP Sydney Silverman to abolish capital punishment[3]. The Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) bill which suspended capital punishment on acts of murder was mooted in 1965 and came into effect in 1970, through a free vote in the House of Commons to abolish it.

The UK Parliament has since undergone various piecemeal reforms, and the PMB system has been refined and strengthened. Arguably, the biggest difference between the Parliaments of the UK and Malaysia – in terms of their PMB systems – is the allocation of time given for Private Member’s businesses.

The UK’s Standing Order 14 (8) guarantees that any PMB has precedence over government business on 13 Fridays in each session, chosen by the House. This stands in stark contrast to Malaysia, where government businesses always trump Private Member’s business on any given day.

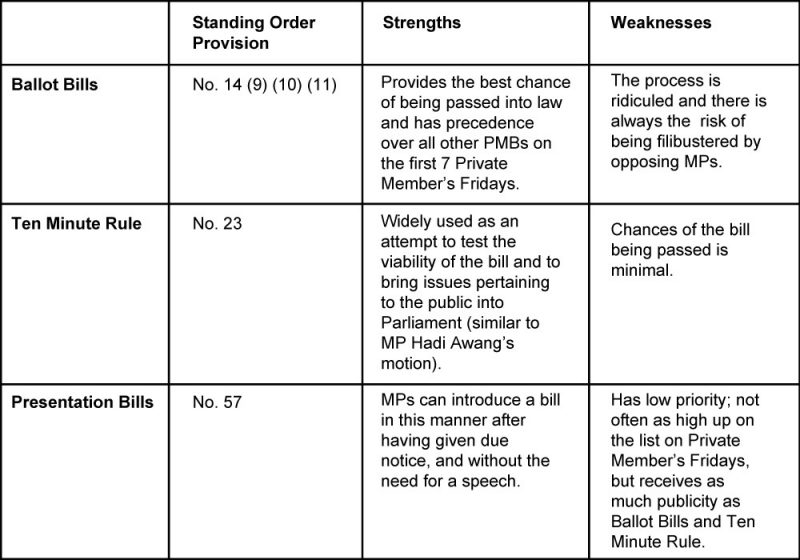

During the period of the 13 Fridays, UK MPs who are not government ministers will have the opportunity and freedom to engage in Private Member’s business without government interference. There are currently three methods of introducing PMBs in the House of Commons (see Table 1).

Table 1: Methods of Introducing Private Member’s Bills in the UK

Ballot Bills have the highest success rate in ensuring that a bill in due process becomes a law, since time is allocated for debate in the second reading of the bill as enshrined in the Standing Order.

At the beginning of each parliamentary session, MPs are treated to a “national lottery” where they are able to submit their PMBs to a ballot. A total of twenty names are later selected, and these MPs will then see their bills formally presented in Parliament on the fifth sitting Wednesday when the bills are deemed to have passed through the first reading.

Subsequently, these bills are assigned a second reading, and having precedence over any Private Member’s business (on the first seven Private Member’s Fridays)[4]. The priority of the selected bills are based on the order in which the lottery lots were drawn. This means that the MPs whose PMBs were drawn first will have the most parliamentary time allocated, a considerable advantage over bills that are drawn after.

The main advantage of the Ten Minute Rule method is its relatively speedy process in bringing a non-governmental bill issue to parliamentary attention. Two Ten Minute Rule bills are presented during each session of Tuesday and Wednesday, if the PMBs are lucky enough to have a slot. The MP whose bill is introduced is allowed to make a case for it in the span of 10 minutes, and an opposing MP may similarly make a pitch to oppose the bill for the same amount of time.

Later, the House may decide if the bill is to be submitted. However, bills introduced via the Ten Minute Rule are liable to remain stagnant after their introductions – should the House decide to proceed further – as there is rarely time allocated for more deliberation. But bills do get passed if sufficient bipartisan support is garnered.

Bills put forward through the Ten Minute Rule are more effective in highlighting a niche issue that would otherwise remain unraised by the government. In some ways, MP Hadi Awang’s Private Member’s motion does mirror the workings of the Ten Minute Rule.

Lastly, the third approach Presentation Bills allows MPs to formally introduce a bill after having given notice. These types of bills are often low in priority and cannot be presented until after the Ballot Bills have all been presented and scheduled for second readings. Bills of this nature have a much reduced chance of being tabled, let alone being passed into law.

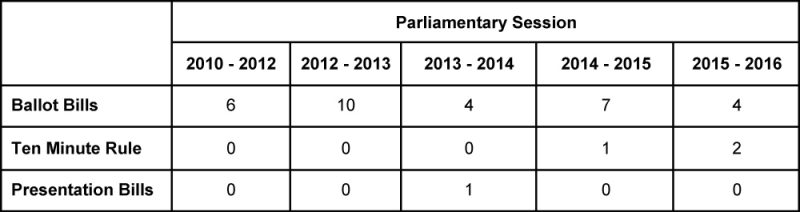

Table 2: Number of Private Member’s Bills to receive Royal Assent under Ballot Bills, Ten Minute Rule and Presentation Bills

Table 2 suggests that, since 2010, Ballot Bills have the best legislation record. Interestingly, all of the 31 Ballot Bills since 2010 received royal assent and were raised by Conservative backbencher MPs under a Conservative government. This might also imply that for a PMB to be successfully passed into law, it will have to rely on the substantial backing and support of the government.

However, critics are quick to argue that PMBs sometimes lack sufficient protection. For example, the progress of the widely supported Voyeurism (Offences) Bill which aims to criminalise up-skirt videos was halted by a shout of objection by a lone MP[5]. Despite that, the bill and its provisions are largely approved of, and have since been co-opted and transformed into a government bill to ensure that it receives royal assent as soon as possible[6].

A Healthy Private Member’s Bill System Produces a More Effective Parliament

Aside from restoring power to (non-government) MPs to legislate the Voyeurism (Offences) Bill, the up-skirting example also proves that PMBs can be utilised to compel the government to recognise certain loopholes within the legal system and to act responsibly in closing them. Ultimately, Malaysia’s Parliament as a democratic institution remains a work in progress. To begin with, it would do well to provide sufficient avenues for the tabling of PMBs, as well as for Private Member’s businesses and amending the Standing Order 15 (1) which highlights the precedence of government business over that of the Private Members’.

The dignity of our Parliament rests on how far we are willing to acknowledge the role of non-government MPs in the legislative branch; their rights as legislators should be protected and not curtailed.

References

Standing Orders of the Dewan Rakyat. https://www.parlimen.gov.my/images/webuser/peraturan_mesyuarat/PMDR-eng.pdf . Accessed November 15, 2018

Standing Orders of the House of Commons – Public Business https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmstords/1020/so_1020_180501.pdf. Accessed November

15, 2018

Parliamentary Hansard of Dewan Rakyat, May 26, 2016. November 24, 2016. April 6, 2017. https://www.parlimen.gov.my/hansard-dewan-rakyat.html?uweb=dr . Accessed November 15. 2018

House of Commons Background Paper: Public Bills. https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/SN06507. Accessed November 15, 2018

Successful Private Members’ Bills since 1983. https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/SN04568 . Accessed November 15, 2018

[1] A Private Member’s Bill (PMB) is a bill (proposed law) submitted by MPs who are not from the Executive branch of government. Thus, a PMB can be submitted by an MP from the opposition or the ruling party as long as he holds no position in the government.

[2] Though they work for the government, non-government MPs are not Private Member MPs.

[3] https://www.historyextra.com/period/20th-century/a-brief-history-of-capital-punishment-in-britain/

[4] According to Standing Order 14 (9), on and after the eighth Friday, the precedence of PMBs shall be arranged in the following order – consideration of Lords amendments, second readings, consideration of reports not already entered upon, adjourned proceedings on consideration, bills in progress in committee, bills appointed for committee, and third readings.

[5] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/jun/17/theresa-may-declines-to-condemn-mp-for-blocking-upskirting-bill

[6] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/718308/voyeurism-offe nces-bill-factsheet.pdf

Managing Editor:Ooi Kee Beng, Editorial Team: Regina Hoo, Braema Mathi, Alexander Fernandez and Nur Fitriah (designer)

You might also like:

![Reducing Moral Hazards in Malaysia’s Public Healthcare System]()

Reducing Moral Hazards in Malaysia’s Public Healthcare System

![Raising the Alarm: Urgent Reforms Needed to Address PISA and Propel STEM Education]()

Raising the Alarm: Urgent Reforms Needed to Address PISA and Propel STEM Education

![Ecotourism: A Sector where Sustainability is Everything]()

Ecotourism: A Sector where Sustainability is Everything

![Podcasts: Challenges and Opportunities for Media Practitioners, Policymakers and Individuals]()

Podcasts: Challenges and Opportunities for Media Practitioners, Policymakers and Individuals

![Heritage Tourism in George Town: A Complicated and Always Controversial Issue]()

Heritage Tourism in George Town: A Complicated and Always Controversial Issue