Executive Summary

- In order to aid the many industries badly affected during the period of Movement Control Order (MCO) it put into place to fight the Covid-19 pandemic, the Malaysian government implemented economic stimulus packages

- Unfortunately, the Arts and Culture Sector was ignored. In fact, despite the fact that this sector plays a large role in the wellbeing of a society and in its economy, it is rarely cited in national or state policy discussions

- Different countries define the sector differently, and consider its importance rather differently as well. This becomes all the more obvious during a multifaceted crisis like the one the world is now facing. The Arts Council England in UK, for example, announced a £160 million (RM 854 million) emergency response package to ensure that organizations in the Arts and Culture Sector are able to continue functioning or to help them get back on their feet again, to support freelancers, and to help disabled artists who have been particularly impacted by the pandemic

- Closer to home, the Singapore government has announced an additional SGD $55 million for the Arts and Culture Sector. The money will be used mainly for major companies and leading art groups to retain jobs within the sector and to enhance the government’s Capability Development Scheme for the Arts (CDSA) that supports the upskilling and professional development of art organisations and practitioners

- What Malaysia urgently needs is to establish a complete support system for the Arts and Culture Sector to ensure minimum support at the very least, for those actors most badly hit by the crisis. This can take the form of skills training, resource sharing and financial assistance. Beyond that, a review for Malaysia’s cultural policy which was drafted in 1971 is necessary since it may no longer meet the requirements of contemporary social situations

Introduction

On March 18, Malaysia’s Federal Government executed a Movement Control Order (MCO) to prevent the further spread of the Covid-19 virus. This necessary move affected many industries very badly, especially in the services sector.

One of the key drivers of the services sector is the tourism industry. During the first half of 2019, Malaysia welcomed 13.35 million international tourists and recorded a 6.8% growth in tourist receipts, which contributed RM41.69bil to the country’s revenue. This amounted to over 7% of Malaysia’s economy.[1] With that in mind, the tourism industry received much attention in the Prihatin Rakyat Economic Stimulus Package (PRIHATIN) – a total allocation of RM10 billion[2] – which was recently announced by Prime Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin on 27 March. The measures include:

- A partnership between Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB) and the Federal Government to introduce a tiered-discount for electricity payment ranging between 15% to 50% according to usage, with a maximum limit of 600 kilowatts per month, valid for six months beginning with bills charged from April 2020;

- The postponement of tax instalment payments to affected businesses in the tourism sector for six

months beginning 1 April 2020, and; - The government will focus on domestic investment activities that have high multiplier effects,

preserving jobs and upgrading tourism facilities.[3]

In Penang, the State Government meanwhile implemented a RM75 million aid package which is expected to benefit approximately 410,000 recipients during the Covid-19 pandemic. This package includes a one-off cash payment of RM500 each to 14,012 licensed petty traders and hawkers, 1,367 registered tour guides and 18,657 welfare aid recipients of the Social Welfare Department; an increase of RM200 in annual incentive to 2,248 taxi drivers and 318 trishaw pullers; as well as a one-off cash payment of RM300 to 10,000 e-hailing drivers.[4]

The Role of Arts and Culture in Tourism

Unfortunately, hardly any discussion in these dire times on the needs of the Arts and Culture Sector has taken place, at the federal or the state level. Though the burden of artists and cultural workers – who are mostly freelancers – may be eased by the one-off cash assistance from PRIHATIN, there has been little to no effort undertaken in sustaining the Arts and Culture Sector as a whole.

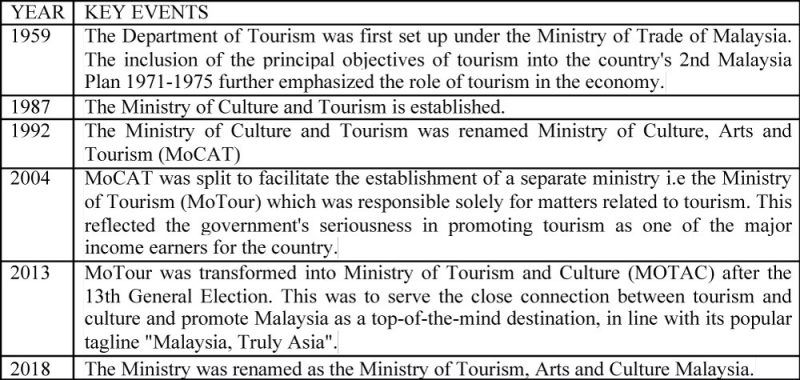

Judging the value of the Arts and Culture Sector from an economic perspective may seem an arduous task. However, the sector plays an essential role in determining the direction of society’s future development. Since 1987, the Arts and Culture Sector in Malaysia has always been placed in the same category as Tourism. This has been acknowledgement of the sector being the basis for tourism, and as the engine attracting visitors to the country. The emerging tourism industry needed to highlight the exciting arts and cultural scene of Malaysia’s diverse society.

The “Malaysia, Truly Asia” marketing and branding campaign that began in 1999 was again an attempt to promote the country’s multitude of cultures, festivals, traditions and customs. Thus, during festivals such as Chinese New Year or Thaipusam, traditional rituals are often accompanied by art festivals, street events and various performances to satisfy tourists.

Table 1: The History of Federal Administration over Tourism, and over Arts and Culture

It has been the richness of the Arts and Culture Sector that has ushered in mass tourism, especially in the case of Penang. Today, tourists are no longer satisfied just contemplating old objects representing cultures alien to them. What they are increasingly seeking are authenticity and experience. Some are willing to travel long distances to achieve this. On the other hand, with the help of various new technologies, getting basic information about another culture can be done, at least superficially, in an instance. As a result, old tour destinations, such as traditional museums, face a major crisis and are often in need of transformation in their methods of presentation.

Concurrently, heritage has gradually become a new focus for tourism. History is to be made more available, and more personal in experience. Amidst discussions on conservation, preservation, restoration, reclamation, recovery, recreation, recuperation, revitalization, and regeneration, heritage offers and injects something new into the present-day tourist experience. There are types of heritage that appear sustainable, and for these, protection is generally not required. Many other types are under threat, however.[8] And so, with the contemporary enthusiasm for living heritage and the great interest in social history and culture, which are all very welcomed, compromises and adaptations in cultural practices naturally occur. The strong link between the arts on one hand and culture on the other has in recent times found expression as “the Creative Industries”.

It should be noted that the terms “Cultural Industries” and “Creative Industries” are often used interchangeably albeit that they are expressions from different periods. Cultural industries arose from the technological advances of the early twentieth century. German philosopher Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno originally used the term to refer to industrially produced commercial entertainment such as broadcasting, film, publishing and recorded music; in contrast to the subsidised “arts”, such as the visual and performing arts, museums and galleries.[9]

Creative industries, on the other hand, are a product of technological changes in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century which dismiss the public’s heavy reliance on big-corporation and mass entertainment. Sadly, when culture is subsumed by the creative industries agenda of economic development, its distinctive aspects are obscured.[10] When arts and culture are seen to be economic in value, and are treated as commodities, their essence is often distorted.

As mentioned earlier, the Arts and Culture Sector is rarely discussed in national or state policymaking. The disruption that the worldwide Covid-19 pandemic brings to policy thinking offers new directions for how society’s basic and complex expressions, and its living history, can be enhanced.

The remainder of this article will discuss how two other countries manage the Arts and Culture Sector and attempt to protect these two domains during the outbreak of Covid-19, and develop them post-Covid-19.

A New Age for The Arts and Culture Sector?

The United Kingdom

Different countries have different interpretations and considerations in defining the Arts and Culture Sector in their policy thinking. In the case of the United Kingdom (UK), the responsibility of arts and culture management falls under the Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). The DCMS has the clear goal of protecting and promoting cultural and artistic heritage, and helping businesses and communities promote the UK abroad for economic purposes.[11]

With its rich historical background, the UK has a relatively progressive mechanism in place to manage museums, archives and the arts. Case in point, the Arts Council England plays its role by championing, developing and investing in artistic and cultural experiences, and supports a range of activities across the arts, and in museums and libraries—from theatre to digital art, reading to dancing, music to literature, and crafts to collections.[12]

Of course, one should not rely completely on information obtained from a government’s official website to judge the institution’s value. However, based on the current sizeable funding and assistance provided to sectors affected by the pandemic, there are lessons to be emulated.

The UK’s national tourism agency, VisitBritain/VisitEngland, funded by the DCMS, provides a long list of advice and support for businesses during the Covid-19 crisis on their website. The announcement mentions financial support for different groups in the form of Small Businesses Grant Scheme; Retail, Hospitality and Leisure Grant Fund; Job Retention Scheme; Self-employment Income Support Scheme and various others.[13] Apart from this, the UK government also provides support for the Arts and Culture Sector. For example, the Arts Council England announced a £160 million (RM 854 million) emergency response package on 24 March to support individuals and organisations to weather the Covid-19 crisis.[14] From the details, approximately £90 million (RM 480 million) will be available for National Portfolio Organisations (NPOs), £50 million (RM 267 million) for organisations outside of the National Portfolio, and £20 million (RM 107 million) for individuals. This fund ensures that these organizations are able to continue functioning despite the crisis, and helps them get back on their feet again. Individuals who can apply to the support fund include choreographers, writers, translators, producers, editors, freelance educators, composers, directors, designers, artists, craft makers and curators – and they are eligible to roughly £2,500 (approximately RM 13,351) per person.

Besides, measures have been introduced to aid disabled artists who have been particularly impacted by the pandemic.[15]

Singapore

In Singapore, the tourism and creative industries are managed respectively by the Singapore Tourism Board (STB) and the Singapore Economic Development Board (EDB), under the Ministry of Trade and Industry. The arts and matters concerning heritage come under the National Arts Council (NAC) and the National Heritage Board (NHB) respectively. Both of these sort under the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth.

On 26 March, the Singapore government budgeted an additional SGD $55 million (RM 168 million) for the Arts and Culture Sector.[16] The funds will be used mainly for major companies and leading art groups to retain jobs within the sector. Collectively, these art organisations are key to the sustaining of a vibrant and mature art scene, and they create opportunities for art practitioners while engaging and growing audiences.

Apart from that, the NAC further enhances the Capability Development Scheme for the Arts (CDSA) to support the upskilling and professional development of art organisations and practitioners. This is meant to prepare the arts and culture organisations and practitioners, including freelancers, for post-Covid-19 recovery until the end of 2020. Meanwhile, the Ministry is encouraging arts and cultural institutions, organisations and practitioners to present their works digitally, to offer new experiences for audiences, and to create new economic opportunities.[17]

To top it off, a Venue Hire Subsidy of 30% for venue rental and associated costs for activities occurring between 7 March and 30 June 2020 was also announced by the NAC, while drop-in chat sessions have been prepared for art freelancers seeking help or advice to manage the Covid-19 situation.[18]

Moving Forward

The biggest issue for policy makers in general, when it comes to helping the Arts and Culture Sector lies in the difficulty of measuring the sector’s output, in relation to its funding, and in justifying grants. The problem gets much worse when a government does not have the required means and expertise – or interest – to oversee and properly evaluate the socioeconomic importance of that sector.

Equipping people in the field with basic knowledge and skills and with the required techniques would go a long way during this challenging period. Take the Digital Culture Network (DCN) from the Arts Council England for instance. Besides offering advice and guidance, it has highlighted existing tools and special offers from tech organisations, and pulled together their resources to help tackle the crisis.[19] Their attempts to bridge different fields and industries garnered support from the government, and the cross-field collaborations that can grow out of this will assuredly enhance the future competitiveness of the various sectors involved.

Providing players in the Arts and Culture Sector with resources and sufficient funds puts them in a good position to be of critical support to the tourism sector, to heritage maintenance and to the creative industries.

What we urgently need in Malaysia today is to establish a broad support system for the Arts and Culture Sector to ensure minimum support at the very least, to everyone in this field to enable them to obtain skills training, resource sharing and financial assistance. Unlike general industrial planning, there is no paradigm approach for artists and cultural workers to emulate. Each challenge they face requires a unique and creative solution. For that reason, arts and culture management needs to become more familiar with the sector’s characteristics and societal value.

Last but not least, Malaysia’s cultural policy which was drafted in 1971 is probably not able to meet the requirements of contemporary social situations, be it in economic value or academic achievement.[20] Thus, a deep review in the definition and significance of the Arts and Culture Sector to equip it for the headwinds of the 21st century is necessary.

[1] Tourism Contributes RM42bil to Economy, The Star, 24th August 2019. https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2019/08/24/tourism-contributes-rm42bil-to-economy

[2] “Prihatin Rakyat Economic Stimulus Package (PRIHATIN) Speech Text.” Prime Minister’s Office of Malaysia. https://www.pmo.gov.my/2020/03/speech-text-prihatin-esp/

[3] “Prihatin Rakyat Economic Stimulus Package (PRIHATIN) Speech Text.” Prime Minister’s Office of Malaysia. https://www.pmo.gov.my/2020/03/speech-text-prihatin-esp/

[4] “Penang announces RM 75 million people’s aid package”, Bernama.com, 25th March 2020, https://www.bernama.com/en/general/news.php?id=1825004

[5] “History”. Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture. http://www.motac.gov.my/en/profile/history

[6] Thomas Adajian, 2018. The Definition of Art. California: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, p2.

[7] Adam Kuper, 1999. Culture: The Anthropologists’ Account. London: Harvard University Press, 1999, p6.

[8] Barbara Krishenblatt-Gimblett. Destination Museum. Destination Culture: Tourism, Museums, and Heritage. University of California Press, 1998, pp. 149-150.

[9] Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception, 1944. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/adorno/1944/culture-industry.htm

[10] Susan Galloway & Stewart Dunlop. A Critique of Definitions of the Cultural and Creative Industries in Public Policy. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 2007, pp.18-19.

[11] “About us”. Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-digital-culture-media-sport/about

[12] “About us”. Arts Council England. https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/about-us-0

[13] “Covid-19 (New Coronavirus) – Latest Information and Advice for Businesses”. VisitBritain/VisitEngland. https://www.visitbritain.org/covid-19-new-coronavirus-latest-information-and-advice-for-businesses

[14] “Covid-19 Support”. Arts Council England. https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/covid19

[15] Abid Hussain. “Diversity and Our Emergency Response”. Arts Council England. https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/blog/diversity-and-our-emergency-response

[16] “Supplementary Budget Statement”. Singapore Budget 2020. https://www.singaporebudget.gov.sg/budget_2020/resilience-budget/supplementary-budget-statement

[17] “Supplementary Budget Statement. Annex B-8: Providing Sector-Specific Support.” Singapore Budget 2020. https://www.singaporebudget.gov.sg/docs/default-source/budget_2020/download/pdf/supplementary_annexb8.pdf

[18] “Sustaining the Arts During Covid-19: Measures to Support the Arts Community During Covid-19.” National Arts Council Singapore. https://www.nac.gov.sg/whatwedo/support/sustaining-the-arts-during-covid-19.html

[19] Digital Culture Network. https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/developing-digital-culture/digital-culture-network

[20] “National Culture Policy”. The National Department for Culture and Arts. http://www.jkkn.gov.my/en/national-culture-policy

Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng, Editorial Team: Alexander Fernandez and Nur Fitriah (designer)