EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Persons with learning disabilities represent 35% of all registered persons with disabilities (PWDs), yet only 92 persons were employed in the civil service between 2020 and 2023 compared to 2,550 persons with physical disabilities.

- Malaysia continues to face labour shortage in low-skilled jobs, with foreign workers filling 48% of these roles. Many of these positions such as cleaning, packaging, and kitchen assistance, match the strengths of persons with learning disabilities.

- International models, such as the United Kingdom’s Access to Work programme, demonstrate that targeted support including job coaches and workplace adjustments can increase employment, boost productivity, and reduce welfare costs.

- By empowering persons with learning disabilities and absorbing them into the workforce, Malaysia can reduce reliance on foreign labour, strengthen domestic human capital, and promote inclusive economic growth.

Introduction

Thousands of young adults with learning disabilities are being left out of the workforce not because they lack the capacity to contribute, but because the labour market is not built to recognise and harness their abilities. This exclusion is costly, both for the affected individuals and for the nation. At a time when Malaysia faces labour shortages in key sectors, overlooking this group means underutilising a capable segment of our population and losing the social and economic benefits that come with their inclusion.

Globally, persons with disabilities (PwDs) make up an estimated 1.3 billion people, or one in six individuals (WHO, 2022). In Malaysia, registered persons with disabilities population reached 674,548 in 2023, with two categories dominating the statistics: physical disabilities (36.3%) and learning disabilities (35.0%). Despite being the second-largest group, individuals with learning disabilities have one of the lowest labour force participation rates. Many are in their prime working years, especially those aged 25–35, yet remain unemployed or underemployed, reflecting a significant gap in the country’s utilisation of human capital.

This persistent underrepresentation is not simply a matter of individual skill levels; it is rooted in systemic barriers, from rigid hiring criteria that overemphasise academic qualifications to insufficient workplace accommodations. International examples, such as the United Kingdom’s “Access to Work” programme, show that with targeted support and inclusive policies, individuals with learning disabilities can thrive in diverse roles and deliver tangible value to employers. Malaysia has an opportunity to replicate and adapt such models, and aim to turn this overlooked segment of the population into a driver of economic productivity and social inclusion.

This paper examines the trends and challenges faced by persons with learning disabilities in Malaysia, with particular attention to their employment prospects and the barriers that limit their role in society. It also considers employer perceptions, and draws on international examples to identify approaches that could inform more inclusive policies. Its main aim is to highlight the urgency of addressing this issues and to outline possible strategies for clearing pathways into meaningful employment.

Trends and prospects of the Malaysia persons with learning disabilities population and employment

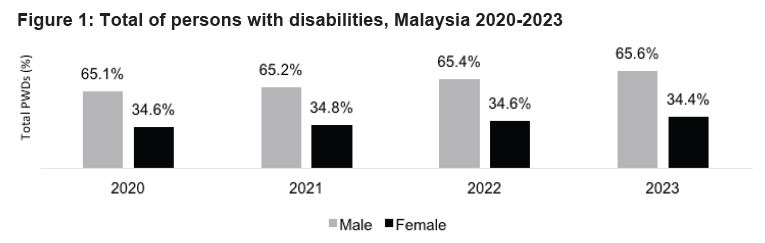

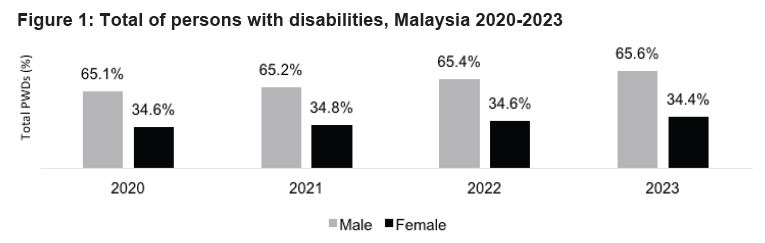

Malaysia has seen a steady rise in the number of registered persons with disabilities over the past four years. According to the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM), persons with disabilities increased from 586,558 in 2020 to 674,548 in 2023, a growth of 15% in just three years. The gender distribution has remained constant, with males representing approximately 65% of the registered persons with disabilities population and females 35%.

Figure 1: Total of persons with disabilities, Malaysia 2020-2023

Source: Calculated and tabulated based on data from Department of Statistics Malaysia (various years)

In 2023, physical disabilities (36.3%) and learning disabilities (35.0%) were the two largest categories among all registered persons with disabilities. Together, these two groups make up over 70% of the total, underscoring their significance in any national inclusion strategy. Yet, despite being the second-largest group, persons with learning disabilities remain one of the most underrepresented segments in the workforce.

Figure 2: Total of persons with disabilities with categories, Malaysia, 2020-2023

Source: Calculated and tabulated based on data from Department of Statistics Malaysia (2020 to 2023)

Learning disabilities, including dyslexia, Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), dyscalculia, dysgraphia, and auditory processing disorder, pose a critical but under-recognised challenge to Malaysia’s human capital development. National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2022 data indicated that approximately 7.4% of Malaysian children experienced developmental delays that affect motor, speech/hearing, and social skills, all of which are closely associated with learning difficulties. Evidence from Universiti Malaya Medical Centre (2025) highlights that such conditions often manifest by age five, disproportionately affect males, and are frequently accompanied by behavioural disorders such as ADHD. Alarmingly, nearly half of these children remain in mainstream classrooms without access to tailored interventions.

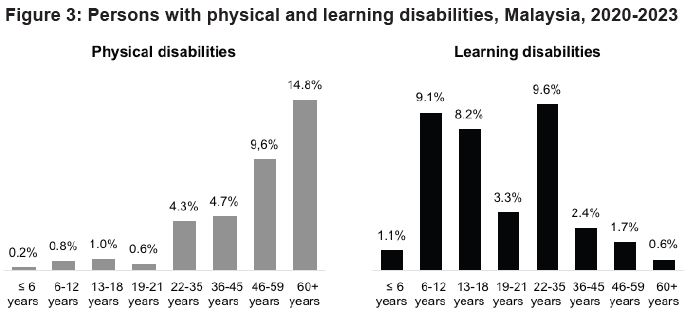

Age distribution data reinforce concerns that individuals with learning disabilities are concentrated in the 6–18 age range, a period vital for foundational learning and skill acquisition. The pattern persists into the 25–35 age group, a key phase for tertiary education completion, skill development, and early career advancement; this highlights the risk of missed opportunities during peak productive years. The average age of this group in Malaysia is 21.6 years, indicating that the majority are still in school or just entering adulthood without adequate preparation for the labour market.

Figure 3: Persons with physical and learning disabilities, Malaysia, 2020-2023

Source: Calculated and tabulated based on data from Department of Statistics Malaysia (2023)

The challenge is further illustrated by civil service employment data from 2020–2023: only 92 individuals with learning disabilities were employed in the public sector compared to 2,550 with physical disabilities, a ratio of roughly 1 to 28. This disparity suggests that systemic factors, rather than individual capabilities alone, are preventing this group from securing stable employment. In the private sector, the situation is similarly constrained: a 2023 employer survey found that only 10.8% of employers reported hiring individuals with learning disabilities, with the remaining 89.2% citing barriers such as job requirements, perceived lack of qualified candidates, and concerns over accommodation costs (RSIS International, 2023).

Figure 4: Number of civil servants with disabilities by category of disabilities, 2020-2023

Source: Department of Statistics Malaysia (2020 to 2023)

Several factors contribute to this gap. Traditional recruitment practices tend to prioritise academic qualifications, inadvertently excluding individuals whose strengths lie in practical, hands-on skills. Additionally, a lack of tailored workplace support such as simplified training materials, structured routines, and job coaching creates barriers to entry and retention (Rahman & Abdullah, 2023; DET Forum, 2020). Without intervention, these may deepen the marginalisation of young adults with learning disabilities, limiting their economic independence and reducing the potential of increasing the living standard of individuals with disabilities.

These barriers can be understood more clearly through three key challenges:

Education-to-employment transition is weak

Learning disabilities are most often identified during school years, yet despite nearly 85,600 students being enrolled in special needs education as of 2019 (The Sun Daily, 2025), Malaysia still lacks a structured pathway that supports young people as they move from education to work. Studies show that while many young adults with learning disabilities have some work experience, only about two-thirds remain employed, with outcomes strongly influenced by gender and access to adult services such as financial support and family networks (Harun et al., 2019).

A 2024 situational analysis by Fora Education further highlights that career guidance and transition planning in schools remain fragmented, with limited tools available to support self-determination, job skills, or employer engagement (ForaEd, 2024). This weak transition pipeline means that individuals often leave school without market-relevant skills or a clear entry point into the labour market.

Fewer supported the employment system

Despite initiatives such as the Job Coach Programme, Malaysia’s supported-employment system remains small-scale and fragmented. Between 2012 and 2018, only 956 persons with disabilities were placed in jobs through job coaches, reflecting weak linkages with industry and limited employer confidence (Rahman & Abdullah, 2023). Services are concentrated within pilot projects, with minimal nationwide infrastructure, while overlapping responsibilities among government agencies result in uncoordinated delivery (Chu, 2019). Neurodiverse groups such as those suffering from dyslexia and ADHD, receive little targeted support, leaving them further marginalised in the labour market (Project Haans, 2023).

Malaysia’s Job Coach Programme remains limited in scale and effectiveness. Many organisations, especially SMEs, have no job coaches, and those available often lack formal training in task analysis, job accommodation, and structured workplace support. Research highlights that job coaching is sometimes carried out without proper certification, reflecting a narrow perception of the role (Rahman & Abdullah, 2023; DET Forum, 2020). Without sufficient numbers of skilled coaches, persons with learning disabilities, including those with dyslexia and ADHD, struggle to access the tailored support needed to sustain employment.

Employer perception is a barrier

Employers are generally open to hiring persons with disabilities but often lack confidence and knowledge about job placement. Many hold stereotypes that undermine the abilities of persons with learning disabilities and perceive them as a potential burden in the workplace. A key issue is that employers are not familiar with the role of job coaches, which limits their willingness to make accommodations (Cheah & Rasdi, 2022).

Survey evidence shows that only 10.8 percent of employers reported hiring disabled persons, underscoring the latter’s limited presence in the workforce (RSIS International, 2023). Beyond practical concerns, negative perceptions in Malaysian society where persons with disabilities are often viewed as welfare cases rather than a contributing workforce, further reinforce their exclusion. Challenging these negative stereotypes is essential in ensuring that persons with learning disabilities are fully acknowledged as part of Malaysia’s workforce, and that they are given equal opportunities to contribute to the economy.

Positioning persons with learning disabilities in elementary occupations

Malaysia’s labour market continues to face persistent shortages in low-skilled or elementary occupations, which are often filled by foreign workers. As of 2024, foreign workers accounted for around 14.4% of the total labour force, but more significantly, they made up 47.8% of employment in low-skilled roles, compared to 8.9% in mid-skilled and 2.6% in high-skilled jobs. In sectors such as agriculture (35.5%), construction (31.2%), manufacturing (15.9%), and services (6.65%), foreign labour dominates, revealing a long-standing reliance that exposes the economy to external supply shocks and policy risks.

Figure 5: Percentage share of migrant’s workers (%)

Source: Calculated and tabulated based on data from Department of Statistic Malaysia (2019 and 2024)

The Malaysia Standard Classification of Occupations (MASCO) defines Code 9: Elementary Occupations as jobs involving simple, routine tasks such as cleaning, packaging, kitchen assistance, and basic manual labour. These roles could be performed by many individuals with disabilities, who often excel in structured, repetitive work (Harun et al., 2019; Mencap, 2017; DFN Project SEARCH, 2023). Despite this suitability, persons with learning disabilities remain vastly underrepresented in the workforce, largely due to misconceptions about their capabilities and a lack of targeted employment pathways.

It is found that 64.9% of young Malaysian respondents were employed, mostly in low-skilled or elementary jobs, and reported that employment opportunities provided them with independence, confidence, and social interaction (Harun et al., 2019). However, job sustainability is often dependent on the presence of understanding supervisors and strong family support, emphasising the need for more formalised workplace accommodations and employer sensitisation.

This evidence demonstrates that persons with learning disabilities are not only capable of contributing to elementary occupations but can also fully be part of a stable and productive segment of the workforce when given the proper support. Embedding structured pathways, awareness programmes, and job coaching into Malaysia’s labour market policies for these individuals would help shift employer perceptions from “risk” to “opportunity”, and create an inclusive solution to labour shortages.

The United Kingdom has established a set of targeted policies and programmes designed to improve employment outcomes for persons with learning disabilities. Unlike Malaysia’s broader disability framework, the UK model focuses on specific practical interventions that connect individuals directly to employers while providing tailored support. This coordinated approach demonstrates how structured pathways, legal enforcement, and government–NGO partnerships can deliver measurable results in inclusive employment.

The following are key initiatives in the UK that support persons with learning disabilities in the labour market:

- Access to Work

A government grant programme that provides direct financial assistance to persons with disabilities, including those with learning disabilities, ADHD, and dyslexia. The scheme covers the costs of job coaches, assistive technology, workplace adjustments, and travel assistance. Evidence shows that Access to Work not only enables individuals to retain employment but also delivers a strong return on investment by reducing welfare dependence and increasing productivity (Sutherland, UK Parliament Committees, 2021). - Supported Internships (DFN Project SEARCH, Mencap)

Work-based programmes for young adults with learning disabilities, typically aged 16–24, who have Education, Health and Care Plans. Internships offer structured, mentored work placements with prominent employers such as Amazon, ASDA, and Whitbread. Participants receive job coach support while gaining 800–900 hours of workplace experience, with conversion rates to paid jobs reaching up to 70 percent in some regions (DFN Project SEARCH, 2023). - Person-Centred Planning (PCP)

Rooted in the UK’s “Valuing People” strategy, PCP ensures that employment and training plans are tailored to individual strengths and aspirations. It shifts the focus from generic placement to personalised support, enabling sustainable job matches. Research indicates that PCP contributes to improved employment outcomes by aligning workplace roles with individual capabilities (Robertson et al., 2007). - Disability Confident Campaign

A voluntary employer accreditation scheme designed to encourage inclusive hiring practices and workplace adjustments. Employers progress through three levels Committed, Employer, and Leader, demonstrating their adoption of inclusive recruitment and retention strategies. Evaluations indicate that Disability Confident enhances employer awareness and improves job opportunities for persons with learning disabilities (Department for Work and Pensions, 2025).

The UK model highlights three critical components of success: (1) enforceable legal frameworks, (2) direct financial and technical support for individuals and employers, and (3) active partnerships with NGOs and businesses.

For Malaysia, adapting these elements such as introducing an Access to Work-style grant, scaling supported internships, and accrediting inclusive employers would help move the focus on broad commitments to specific, actionable reforms that directly benefit persons with learning disabilities.

Recommendations

Addressing the persistent challenges faced by individuals with learning disabilities in the Malaysian labour market requires a concerted, multi-stakeholder approach. To foster a truly inclusive and equitable employment landscape, recommendations are directed towards the government and relevant agencies, employers, and society at large.

Establish a dedicated employment support scheme

The rising participation of individuals with learning disabilities in the workforce calls for a dedicated financial support mechanism that ensures fair access to employment opportunities. A scheme modelled on the UK’s Access to Work programme would provide direct funding for job coaching, assistive technologies, workplace adjustments, and transport assistance. Such a grant is crucial to ensure that individuals with learning disabilities are not disadvantaged in recruitment, retention, or career progression simply because of the additional support they require.

The structure of this grant must also be adaptive to the realities of different sectors. For example, adjustments required in hospitality or retail may differ from those in manufacturing or office-based services. By tailoring support to sectoral demands, the scheme would encourage employers across various industries to adopt inclusive hiring practices without fear of additional costs or administrative burdens. Most importantly, this approach would balance the responsibility between government and employers helping businesses address practical needs while ensuring that persons with learning disabilities receive the resources necessary for sustainable and meaningful employment.

Expand vocational training and supported apprenticeships

The increasing number of individuals with learning disabilities entering labour market highlights the need for vocational training that builds on their diverse strengths. For some, especially those who thrive in structured and repetitive environments, elementary jobs such as cleaning, packaging, or kitchen assistance can provide a suitable entry point and pathway to independence. However, it should be noted that many individuals with conditions such as dyslexia or ADHD are high-functioning and capable of excelling in mid- and high-skilled roles when provided with appropriate support (Cheah & Rasdi, 2022; Mencap, 2017). Training modules must therefore be flexible and differentiated, acknowledging that the skills and support needs of each group vary widely. A uniform approach is unlikely to be effective; instead, training should be adaptive and responsive to the varying capacities of each group.

Supported apprenticeships are a critical complement to classroom training. By working in close partnership with industries, these apprenticeships provide structured, real-world experience combined with mentoring and job coaching. Embedding such schemes in sectors with persistent labour shortages such as hospitality, retail, logistics, and basic manufacturing ensures that individuals with learning disabilities are equipped with relevant skills while employers benefit from a more reliable workforce.

Strengthening the legal framework for inclusive employment

Malaysia’s Persons with Disabilities (PWD) Act 2008 provides a solid legal framework for equal rights in employment, but greater focus is needed on translating its provisions into measurable outcomes.

Strengthening regulations and guidelines are necessary to ensure that the benefits and welfare of persons with disabilities are protected against any discrimination. In addition, Malaysia could consider introducing sector-specific quotas or targets for hiring persons with disabilities, ensuring that different industries contribute fairly to inclusive employment while reflecting their unique workforce needs. The most important principle behind the regulations and guidelines is that “one–size–fits–all” may not be practical.

Ensuring greater inclusion of person with learning disabilities in the labour market is not only a matter of social equity but also an economic necessity for Malaysia. By adopting targeted policies and fostering employer readiness, the country can unlock the potential of this underutilised group and build a more resilient and inclusive workforce.

References

Adenan, A. S., Rahman, M. M., Puteh, S. E. W., Safii, R., Saimon, R., Yong, C. Y., & Hock, T. C. (2024). Employment Opportunities and Benefits for People with Down Syndrome in Malaysia: A Qualitative Research. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 26(1), 140–158. https://doi.org/10.16993/sjdr.1064

Bloomer, A., & Bloomer, A. (2024, July 10). Access to Work scheme under serious threat, say campaigners – Learning Disability Today. Learning Disability Today – Supporting professionals working in learning disability and autism services. Link

Chu, S. W. (2019). Assessment Of Quality Standards Of Supported Employment By In-House Job Coaches And Employees With Disabilities (By Universiti Sains Malaysia). PDF

Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM). (2023). Person with Disability Statistics (PWD), Malaysia, 2023. https://www.dosm.gov.my

Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM). (2022). Person with Disability Statistics (PWD), Malaysia, 2022. https://www.dosm.gov.my

Department of Social Welfare Malaysia. (2021). Job coach programme for persons with disabilities. https://www.jkm.gov.my

Disability Confident Scheme: findings from a survey of participating employers. (2023, September 18). GOV.UK. Link

Disability Confident committed. (2025, July 4). Department of Work & Pensions. Link

Government Digital Service. (2015, January 14). Access to Work: get support if you have a disability or health condition. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/access-to-work

Ganeson, D. (2025, January 7). Parents dissatisfied with special needs education. thesun.my. Link

Harun, D., Din, N. Cheah., Rasdi, H. F. M., & Shamsuddin, K. (2019). Employment Experiences among Young Malaysian Adults with Learning Disabilities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010115

Kaur, D. (2023, May 19). Comorbidities in neurodiversity. Project Haans. Link

Khoo, W. V., Jayanath, S., Ng, N. J. H., Loh, N. a. J. C., & Goh, N. J. W. (2025). Provision of health services for children with learning difficulties: A retrospective study at a tertiary centre in Malaysia, Universiti Malaya Medical Centre 30(1), 305–312. https://doi.org/10.54029/2025ntw

Lee, M. N., Abdullah, Y., & Mey, S. C. (2011). Employment of People with Disabilities in Malaysia: Drivers and Inhibitors. International Journal of Special Education (IJSE), 26(1), 112–124. PDF

Matthew. (2024). Transition from Education to Employment in Malaysia: Situational Analysis of Youth with Disabilities. In Transition for Youth With Disabilities in Malaysia (No. 2024–04). PDF

Mencap. (2019). Learning disability and employment. PDF

National Supported Internship Day | DFN Project SEARCH. (n.d.). DFN Project SEARCH. https://www.dfnprojectsearch.org/national-supported-internship-day

Omar, M. K., Li, Y. C., Jamaluddin, F., Rashid, A. M., Saripan, M. I. (2024, December 11). Examining Hindrance Factors for Hiring People with Disabilities (PWDs) in Malaysia: Employer’s Perspectives – International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science. Link

Pang, J. C. (2013, December 31). The Experiences of Employers in Employing Persons with Learning Disabilities in Malaysia. Link

Pettinicchio, D., & Maroto, M. (2024). Disability-based labour market inequalities. In European Trade Union Institute, Working Paper 2024.08. ETUI. PDF

Robertson, J., Emerson, E., Hatton, C., Elliott, J., McIntosh, B., Swift, P., Krinjen-Kemp, E., Towers, C., Romeo, R., Knapp, M., Sanderson, H., Routledge, M., Oakes, P., & Joyce, T. (2006). Person-centred planning: factors associated with successful outcomes for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 51(3), 232–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00864.x

Sutherland, K., Cash. (2021). Written evidence submitted by Kath Sutherland (-Cash) UK Parliament. (ATW0319). In Written Evidence.

Tan, P. (2020). DET Forum Malaysia | Disability Equality Training Forum. https://detforum.com/det-forum-malaysia/

UK Public General Acts. (n.d.). Equality Act 2010. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/section/6

Whitbread PLC. (2024, February 13). Thrive Programme – Whitbread PLC. https://www.whitbread.co.uk/sustainability/opportunity/thrive-programme/

Whitworth, D. (2025, July 2). The Amazon internship giving hope to autistic people like us. The Times. Link

World Health Organization. (2022). Global report on health equity for persons with disabilities.

Yusop, S. Z., Nordin, M. N., Zainal, M. S., Fakulti Pendidikan, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, & Sekolah Kebangsaan Jalan Enam, Bandar Baru Bangi. (2024). Job Coach development in Career Transition in Malaysia. International Journal of Academic Research In Business And Social Sciences, 48. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v14-i8/22358

You might also like:

![Pluvial Flood Management: Critical Need for Holistic Stormwater Mitigation in Penang]()

Pluvial Flood Management: Critical Need for Holistic Stormwater Mitigation in Penang

![EU-Malaysia Trade Ties Strengthen despite Persistent Differences]()

EU-Malaysia Trade Ties Strengthen despite Persistent Differences

![George Town Heritage Celebrations: Achievements and Reflections]()

George Town Heritage Celebrations: Achievements and Reflections

![Covid-19 in 2022: A More Optimistic Landscape Emerges]()

Covid-19 in 2022: A More Optimistic Landscape Emerges

![Penang’s Economy to Remain Robust Despite Global Uncertainties]()

Penang’s Economy to Remain Robust Despite Global Uncertainties