Executive Summary

- As the aged segment of society increases proportionately, the need also rises for nation-wide long-term strategies to address the need for welfare and community-based facilities for elderly persons on the one hand, and to encourage the young to have more offspring on the other

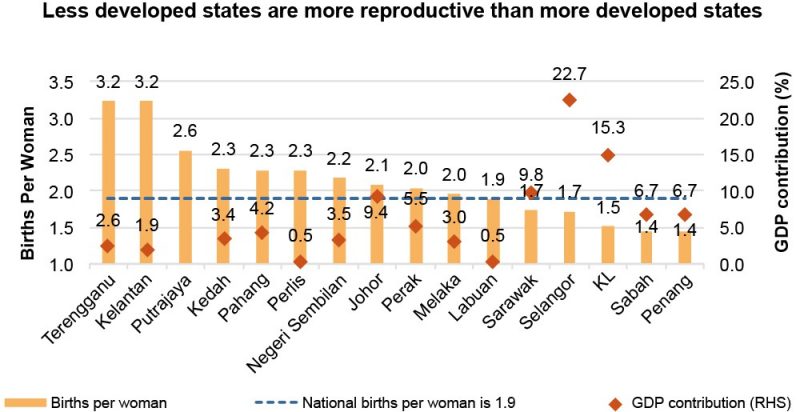

- Low reproduction rates lead very quickly to a smaller prime-age workforce. Most worryingly, Malaysia’s more developed regions, such as KL, Penang and Selangor, have much lower reproduction rates in comparison to other states

- Growth in the working-age population is vital to the national economy. Long-term plans are therefore needed to tackle this detrimental demographic transition, for example, by getting the workforce from states with higher fertility rates to relocate to the more developed states which are experiencing declining birth rates, and also by sourcing for international high-skilled workforce

Introduction

The global demography has shown a steady decline in fertility rates since 1950, and live births have halved from five babies per woman in 1950 to 2.5 babies in 2015. Economists believe economic performances will suffer if no specific measures are taken to mitigate the demographic transition.

In Malaysia the changing demographic landscape is rarely monitored by policymakers and how population trends may impact economic development are not properly considered. Undoubtedly, these patterns should affect a broad range of policies, including healthcare, wealth creation, human capital and community service. Long-term demographic strategies are therefore needed if the aging population is to be properly cared for, and if human capital requirements are to be met.

To be sure, there are a number of policies in place to address the changes in family development and the issue of older persons. During the midterm review of the 4th Malaysia Plan (1981-1985), the government considered the increase in population growth to be beneficial for national development goals. However, research done for the Second Population Strategic Plan Study 2009 found that the size of families is diminishing, and the total fertility rate is on a decline. To address the issue, a number of population-related policies have been constructed. These are the National Social Policy (2003), the revised National Women Policy (2009), the National Policy for Older Persons (2011) and the National Policy on Reproductive Health and Social Education (2009).

Penang’s Demographic Trends: A Case Study

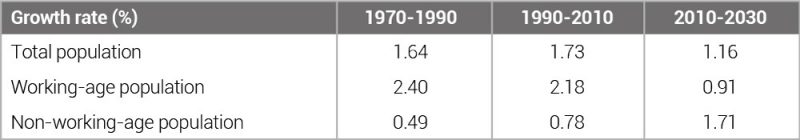

Based on Table 1, the working-age population in Penang has been growing at a slower pace in comparison to earlier decades. The growth rate of the working-age population – between the ages of 15 and 64 – is expected to decline further in the next 10 years.

Table 1: Annual Population Growth Rate for Every 20 Years in Penang

The increase in the non-working-age population (those above 65) outpaced the increase in the younger cohorts aged below 15 years old. This situation requires critical attention as it can subsequently affect the working-age population.

In-migration of workers should not be the main solution in resolving the aging population issue. The matter should be further examined against the backdrop of the skills shortage. The skills shortage is more pronounced in the blue-collar economic sectors due to the out-migration of both blue and white-collar workers to neighbouring countries.

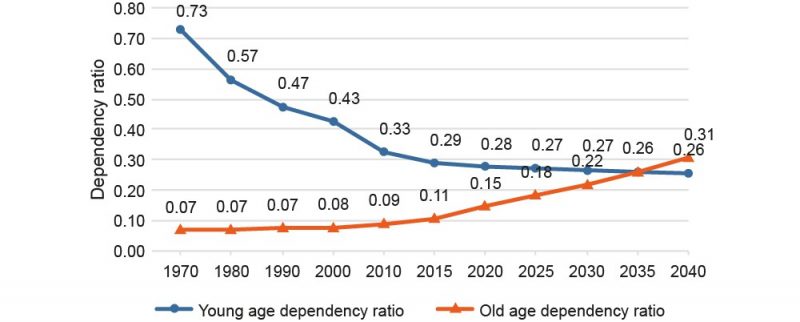

Evidently, there exists a trend reversal between the young and old age dependency ratios from 1970 to 2015 (Figure 1). The former ratio fell significantly, while the latter has been on a steep rise since 2015. If the ratio of working-age population and non-working-age population is stabilised, the number of people entering the workforce can also be gradually steadied.

It is estimated that the old age dependency ratio will surpass the young age dependency ratio by 2035, and therefore the five-year Malaysia Plan should be continuously monitored with regards to population and family planning policies to manage societal burdens and productivity losses.

Figure 1: Young and Old Age Dependency Ratios in Penang from 1970 to 2040

Low Life Reproduction

While increasing female labour force participation is a solution for the demographic shift, studies found

that females’ fertility rate also tends to decline as more women participate in the workforce.

Despite the fact that the proportion of Penang’s married workforce has improved to nearly 60%, the likelihood of women having more than two children is still low. This shift is a relative norm across the region in countries such as China, Japan and South Korea, as well as South-East Asia and South Asia.

As the working-age population share increases, with a reduction in fertility rate and an increase in life expectancy, income per capita and output are elevated with a lowered number of dependents per household. However, if the working-age population reduces, the economic growth may be substantially affected.

Adding to this, having children later in life is common today. This is evident in Chinese and Indian families. Conversely, the Department of Statistics Malaysia has traced the highest fertility rate of Bumiputeras to 2.5 live births per woman compared to 1.3 live births for Chinese and Indian women respectively.

Malaysia recorded the lowest ever fertility rate in 2016. The 2017 Malaysia Vital Statistics published by the Department of Statistics showed a fertility rate of 1.9 babies per woman aged between 15 and 49. This is lower than the global average fertility rate of 2.5 babies born per woman based on latest figures from the World Bank.

Also according to the United Nations (UN), Malaysia stands below the replacement level fertility of

2.1 babies. This indicates that the average number of children born to a woman is not sufficient to

replace herself and her spouse.

No doubt, in the short term, economic efficiency and poverty reduction can be improved. The proportion of working-age population increasing with the reduction in child population results in a low dependency ratio. The cost of supporting a smaller family becomes relatively lower.

But this may not be sustainable over the long haul. Countries with low fertility rates and high economic growths such as Singapore (1.2 births per woman in 2015) encourage the in-migration of knowledge workers through citizenship and residency investment as a measure to increase its working-age population. In China, which once had a one-child policy, in order to boost its low replacement level fertility (1.6 births per woman in 2015), the Chinese government revised its policy in 2016.

Furthermore, the level of economic development varies regionally in terms of fertility rate in Malaysia. Terengganu and Kelantan make up only 2.6% and 1.9% of the national economy, but have the highest fertility rates, with 3.2 children born to a woman (Figure 2). At the same time, life reproduction is much lower in the more developed states. Penang, KL and Selangor recorded fertility rates that are below the national average, and each woman in these states gave birth to just 1.4 babies, 1.5 babies and 1.7 babies respectively in 2016. These low fertility rates are counter-balanced by inter-state migration that is generated by job placements and education opportunities.

To surmise, fertility rates tend to fall as the economy prospers. A study conducted by Bloom et al. (2001) indicates that fertility flourishes in less developed countries, and the share of world population diminishes in the more developed regions.

Figure 2: GDP Contribution (%) and Births Per Woman by States in Malaysia, 2016

Note: Putrajaya’s GDP growth rate is not made available.

Labour Supply Continues to Boost for Older Persons But Not for Younger Cohorts

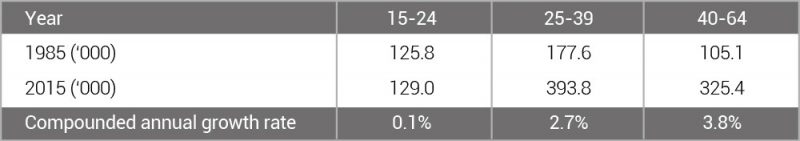

The labour force structure is skewed towards the older cohorts. Due to greater opportunities for higher education attainment, the availability of youth labour force aged between 15 and 24 years old shrank by half from 30.8% in 1985 to 15.2% in 2015, though the labour supply has since doubled.

However, the older cohorts aged 40 and above grew faster than prime working-aged cohorts (25 to 39 years old), with a rate of 3.8% annually compared to the latter’s 2.7% growth (Table 2). This reflects the need of increasing the talent within the prime working-age population.

In Penang the tertiary-educated labour force quadrupled along with a three-fold decline among primary-educated labourers in the last 30 years, while the secondary-educated labour force made up the largest proportion within the overall labour force. This cohort is likely in need of training in forefront technological competences in light of the rise in automated processes.

Be that as it may, Penang’s workforce is relatively more educated than the national workforce. While the national tertiary-educated workforce has improved, its proportion has been larger in developed states such as Penang (32.4% versus 27.7% in Malaysia for 2016), KL (42.7%) and Selangor (37.6%). For workers with primary-level education, the proportion of national labour supply is larger than the share in Penang.

Table 2: Annual Growth Rate for Penang’s Labour Force

Recruiting foreign workers is a widely used measure to satisfy labour needs, even if policymakers are usually concerned about the influx of low-skilled foreign workers into the country. In gearing towards a knowledge-based economy, it is imperative that Malaysia leverages measures on increasing the talented workforce instead.

In fact, many developed countries resolve the labour issue by hiring foreign human capital based on an identified skills shortage list. For example, the Department of Jobs and Small Business of the Australian government has a periodically updated list of skill shortages for the recruitment of migrant workers in occupations that are needed in specific metropolitan areas. These include sonographers, architects and automotive electricians.

Policy Implications and Suggestions

A sustained working-age population is vital for a country to enable continued economic growth. The diminishing number of new births signals an impediment if no long-term demographic plans are in place to respond to the needs of economic growth. Inevitably, this will push wages and prices upward, and more resources will be needed to plan infrastructure and housing for elderly persons.

Though migrant workers provide a quick remedy for the lack of young talent in the country, a question one should ask is what quality level of migrant workers are being brought in to fill the critical positions in the country? At the moment, the majority of migrant workers brought in by the thousands are to work in dirty, dangerous and demeaning (3D) jobs.

In addition, the working culture is likely to change following the rise of the gig economy.[1]

Traditional and corporate employment policies may soon not be applicable due to the technological influences that are rapidly changing the nature of work. This will pose challenges and insecurity for employers.

To achieve sustained economic growth, the government should review its policies concerning women and elderly persons. Socially-inclusive and community-based long-term strategies to tackle the low birth rates in developed states are necessary to encourage ideal family planning for young couples, and enhance healthcare and social security for elderly persons.

Community-driven amenities for the elderly and family-friendly policies, including childcare centres are needed to support the older and younger populations. However, it is important to differentiate community amenities for the elderly from old folks’ homes. In the former, the elderly spend their time within the community, unlike the case in the latter.

Lastly, policymakers should take advantage of the internal and external resources from the demographic transition. These include on the one hand attracting the workforce from states with higher fertility rates to relocate to states with declining birth rates through education and employment opportunities; and on the other, developing an exhaustive, region-specific immigration policy pertaining to the list of skills needed. This must be made fully accessible to all nations to ensure that labour market requirements, especially for the high-skilled segment for economic advancement, are properly met.

References

An, C.-B. and Jeon, S.-H. (2006). Demographic change and economic growth: An inverted-U

shape relationship. Economics Letters, 92, 447-454.

Australian Government (2018). List of skill shortage. Department of Jobs and Small Business.

Retrieved from https://docs.jobs.gov.au/documents/skill-shortage-list-australia

Bloom, D. E., Canning, D. and Sevilla, J. (2001). Economic growth and the demographic transition. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper.

Bloom, D. E. and Finlay, J. E. (2009). Demographic change and economic growth in Asia. Asian

Economic Policy Review, 4, 45-64.

Shahjahan, A., Khandaker, J. A., Shafirul, I. and Morshed, H. (2015). An empirical analysis of population growth on economic development: The case study of Bangladesh. International Journal of Economics, Finance and Management Sciences, 3 (3), 252-259.

[1] A gig economy is characterised as independent contractors who work part-time or temporarily, and hold many flexible jobs. The gig economy undermines the traditional economy of full-time workers who rarely change positions.

Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng Editorial Team: Regina Hoo, Lim Su Lin, Nur Fitriah, Ong Wooi Leng

You might also like:

Four Tourist Zones in Penang: Suggestions to Secure Their Future

Performance Sustained during Covid-19 Highlights Strong Fundamentals in Penang’s Trade in Goods

The Policing and Politics of the Malay Language

A Proposal for Carbon Price-and-Rebate (CPR) in Malaysia

Investment Facilitation: A One-Stop Mechanism Needed to Assist Investors in Penang and Malaysia