EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- A high degree of immunity in the population, acquired through vaccination or previous infection, combined with a less virulent variant (Omicron), has changed the dynamics of the Covid-19 pandemic for now. Pressure on healthcare services is now manageable despite high infection rates, which allows for most economic activities to operate as normal.

- Carrying on with the vaccination process at full intensity is nonetheless still required, to administer booster jabs to the greatest number of adults, and to vaccinate children so that schools can stay open safely.

- Economically, countries with higher vaccination rates see higher upward revisions of growth. This also applies to Malaysia. High-frequency indicators like mobility are close to their pre-pandemic highs, but the economy has not yet recovered entirely. Short-term support for specific sectors (e.g., travel and tourism) therefore remains necessary. There still is enough fiscal capacity for this.

- In the longer term, policies should focus on increasing our resilience to threats of the “anthropocene” (the next pandemic, climate change), and build on the opportunities offered by shifting manufacturing and supply chain models in the wake of the pandemic.

- A high degree of geopolitical and economic uncertainty in the short and medium term will require policymakers to be nimble and flexible in adjusting policies.

Introduction

A year ago, practically all policy discourse was about dealing with the global pandemic that had disrupted practically all aspects of life and challenged long-held views and beliefs. Policy proposals focused on immediate support for the public and the economy, and little attention was paid to the medium or long term.

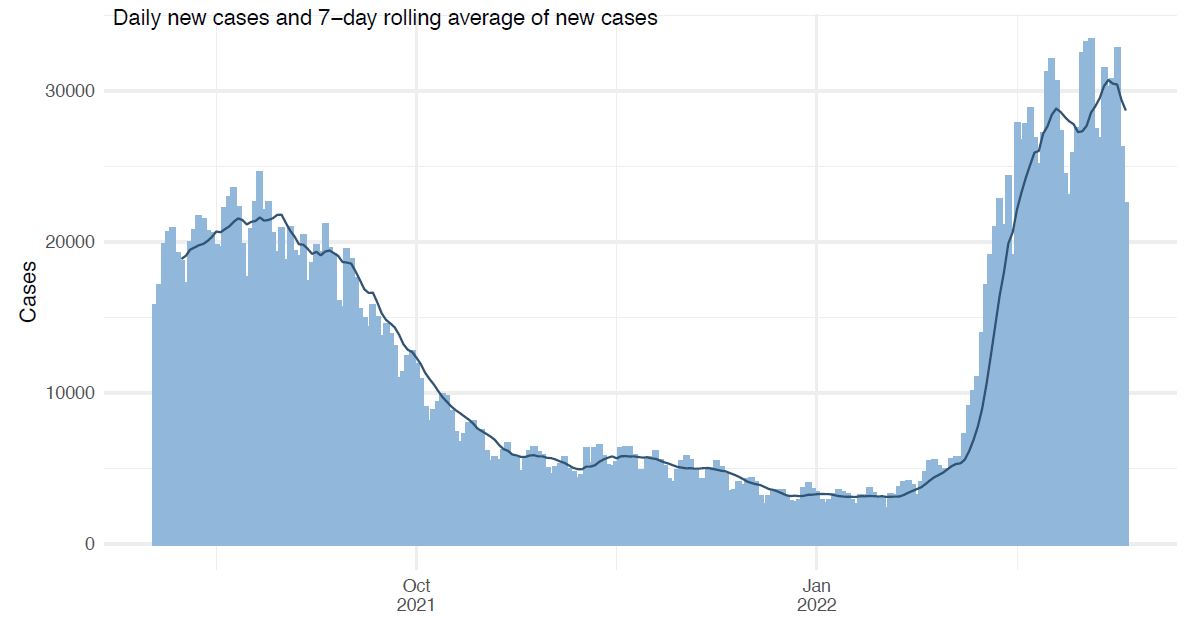

A lot has changed since then. We had harboured the thought that dealing with the pandemic might be a one-time effort, and that we could return to “normal”, once that effort had been expended. As we experience another surge in cases due to the latest variant Omicron, it is now clear that the Covid-19 pandemic is characterised by successive waves of infections, set off by new variants of the virus (see Figure 1 for the latest case count due to the Omicron wave.) On the other hand, there has been a massive and concerted effort to get people vaccinated. The resultant rise in immunity among the population has lessened the deadly effects of Covid-19, and now allows for a gradual relaxation of the stringent measures to control the pandemic. Taken together, we can now reasonably conclude that instead of a one-time effort, we will probably need permanent vigilance and corrective action (such as annual jabs) to keep the virus in check, to allow us to move from a pandemic phase and stay in an endemic state, in other words.

Figure 1: New cases are increasing quickly

The deleterious effects on the economy will reduce in tandem, although as of now it has not returned to “normal” either. Certain sectors are still badly affected by Covid, either because of restrictions on movement, rising infection rates, or more likely, a combination of the two. These sectors will require extended support, and realistic recovery plans for the future. On top of that, specific areas of concern also need to be addressed urgently, primarily to increase our resilience in the face of the next epidemic. Among others, this will require a plan for targeted infrastructure investment, encompassing not only the traditional, hard infrastructure but also soft infrastructure such as hospitals, health research institutes and schools. The focal point of hard infrastructure investment will shift as well, with climate-related infrastructure such as drainage systems and green energy generation, taking centre stage. Increasing resilience is about dealing with future risks, and climate change ranks at the top of that list.

Financing these investments will require significant public spending, but it is also important not to overstretch, especially after a pandemic which has already put a significant strain on the finances. The good news is that Malaysia’s credit situation is comparatively sound, and hence there should be space for these investments.

At this point, the longer-term challenges and opportunities uncovered by the pandemic are also coming into sharper focus. It did not only expose weaknesses in our economic and social systems at home, but also internationally, in particular the fragility of global supply chains. Over the coming years, the private sector will move to address this fragility, for example by diversifying their production locations and building in more slack. Malaysia should ensure that it is not wrong-footed by these changes, and instead position itself to take advantage of them.

Lastly, the levels of uncertainty in the economy are higher than they have been for perhaps 30 years. The effects of the pandemic have been compounded by a series of other crises, both domestically and internationally, giving new prominence to the idea of a “polycrisis”, where different challenges not only arrive at the same time, but feed off each other to increase doubt and uncertainty. The latest development that thoroughly shuffles the cards is of course Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Most of this analysis was written beforehand, and at this stage it is far too early to derive lasting conclusions, but uncertainty has again increased a few notches. Policymakers will have to be nimble in their analyses and recommendations.

Learning to live with Covid-19?

From the early days of the pandemic, the “Find, Test, Trace, Isolate, Support” (FTTIS) framework was the cornerstone for controlling the rate of infections. We now know that SARS-CoV-2 transmits asymptomatically and mutates quickly, in ways that allow it to evade previously acquired immunity, be this through previous infection or vaccination. The pandemic hence tends to progress in waves: each time a variant emerges with a particular evolutionary advantage, it tends to cause a new spike in infections, which quickly spreads from the country where the variant originated to the rest of the world.

However, while the vaccines are not perfect in preventing infection, they significantly increase resistance to death and severe disease linked to Covid-19. This dynamic of new variants on one side, facing a relatively robust immunity in the population on the other, drastically changes the approach to FTTIS.

With the early variants, FTTIS worked well in some countries, particularly in East Asia, but less well in others, particularly in the West, where the rate of infections quickly overwhelmed the resources dedicated to contact tracing. Even an unexpected cooperation between the two biggest smartphone makers Apple and Google, normally fierce rivals, did not succeed in facilitating this process. In this case, blunt lockdowns were the only option to slow the disease.

With the new variants identified so far, the incubation period before a patient becomes infectious has shortened, especially so with the Omicron variant.[1] This may render the FTTIS approach less effective, especially one that relies on PCR testing, where the result can take 24 to 48 hours to become available.

The widespread availability of self-test kits (based on so-called “Lateral Flow Tests”–LFT) provides a new tool though. While they are less sensitive than PCR and antigen tests, LFTs have been shown to be effective at identifying infected patients, and even better, a positive result on the test correlates with the period during which patients are infectious to others. Asking people to use these self-tests, especially before a high-risk event or situation, is therefore one way to reduce the rate of infections.

Nonetheless, despite the overall “overpromise and underdelivery” of FTTIS, some of the components remain useful, such as trying to prevent infection clusters, or at the very least being aware of them, and supporting patients from a healthcare and economic perspective. Since Covid-19 is bound still to cause disruption in the near future, it is important that we keep these processes working.

Vaccines: Silver bullet after all?

Once vaccines became available, FTTIS became FTTIS+V, developing to include widespread vaccination as an integral part of the framework. This turned out to be a resounding success. Medically, the vaccines work, and a vast majority of the population was vaccinated in record time.[2]

In fact, in countries with a high degree of vaccination such as Malaysia, and also several European countries, the fifth wave caused by the Omicron variant has seen a decoupling of the number of infections and hospitalisations.[3] This has prompted some to declare this wave the moment at which Covid-19 went from pandemic to endemic, like the flu or common cold.[4] On cue, governments across Europe started lifting almost all restrictions, for example in the UK and Denmark.

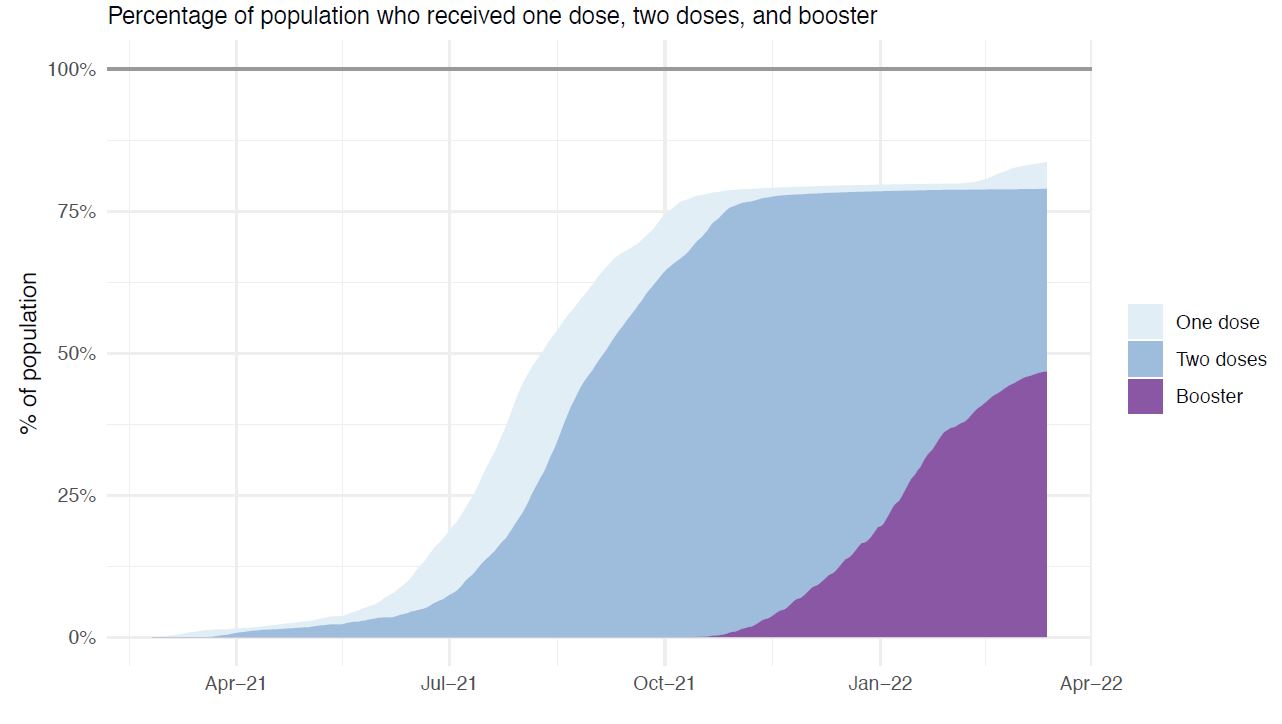

Figure 2: Overall vaccination coverage is high but booster uptake sluggish

It may be too early to declare victory, however. First, the immunity provided by the vaccines wanes rapidly. This means the extraordinary drive to get everyone fully vaccinated the first time round must become at least semi-permanent, ready to provide booster shots at regular intervals. In this sense, Covid-19 becomes somewhat like the seasonal flu; but because at this stage the population is significantly less immune to Covid-19 than the flu, the required vaccination effort is significantly greater.

The question then becomes whether the current vaccination infrastructure, relying on massive mobilisation of personnel and big vaccination centres, is sustainable for the long term. Policymakers should start planning and implementing how the necessary vaccines can be delivered effectively and efficiently for the long haul.

Second, a new variant that is both more infectious and more severe could yet emerge. While admittedly a worst-case scenario, it cannot be excluded, especially when the number of infections with the Omicron variant exceeds all previous peaks in the pandemic, thereby providing more opportunities for the virus to mutate.

And third, the increase in immunity in the population is unevenly distributed. At a global level, differences between countries are glaring, so it is premature to declare a global end to the pandemic, and this means everyone remains at risk, among others because of mutations. Addressing this imbalance should be top priority now for the global community.

Jab, jab, jab

Continuing with the vaccination campaign is a no-brainer. The first priority should be to step up the pace of the booster shots, which only some 55% of Malaysians have received so far. The second priority is to increase coverage to all eligible population groups, including adolescents and children.

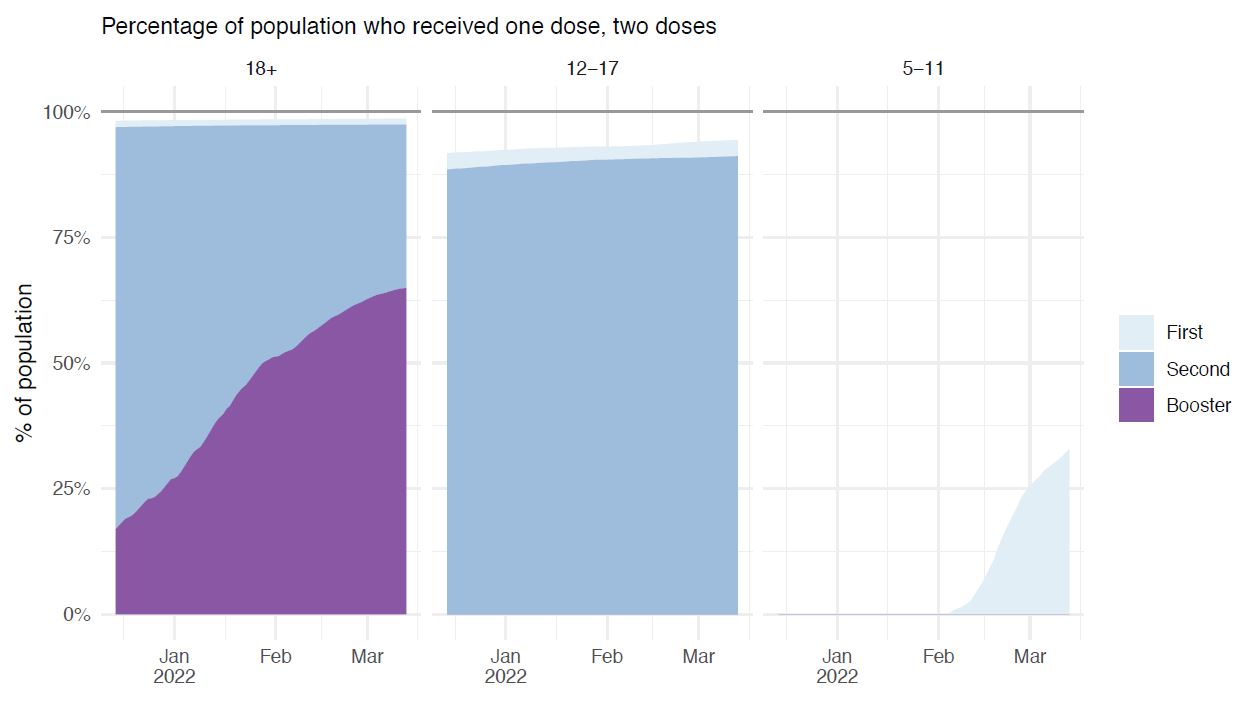

Figure 3: Vaccination percentage in children and adolescents

Motivating the greatest number of people to volunteer for the vaccinations also remains necessary, at least in the short term. In this respect, while constraining for the population, mandatory vaccine certificates to participate in certain activities have been shown to encourage uptake of the vaccine.[5] Given the dynamics of the pandemic, these constraints may remain with us in some shape or form for a few years to come.

Re-open the schools

Despite Covid’s characterisation as a disease that mostly affects older people, vaccines also appear to provide significant individual and collective benefits for children under 12. Indeed, although Omicron seems to cause milder symptoms than previous variants for adults, children are at a small but non-negligible risk of developing multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C) after a Covid-19 infection. Drawing lessons from other infectious diseases, increasing children’s immunity through vaccines instead of letting them get infected is preferable[6] and should be the government’s focus. We are seeing rapid progress, with some 25% of the 5-11-year-olds having received one dose. But there is still some way to go.

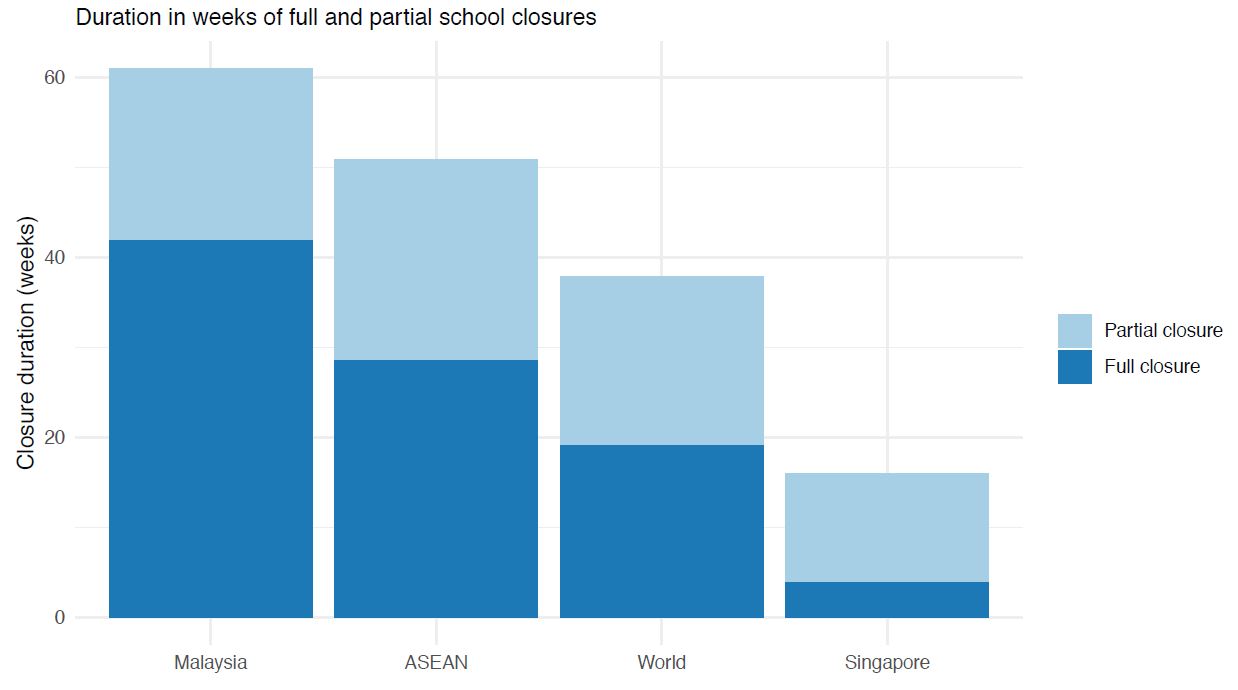

Beyond the immediate health impact, another reason to push ahead with children’s vaccinations is to reopen schools fully as quickly as possible. Schools have been fully or partially closed in Malaysia for significantly longer than the ASEAN and global averages, not to mention Singapore, which made keeping schools open an explicit policy priority.

Figure 4: School closures in Malaysia are longer than ASEAN and world averages

The contribution of education to social mobility and better life outcomes in general is well established, and initial research on the impact of school closures during the pandemic[7] is alarming. They result in a significant education deficit, especially for lower-income groups. Though some of that deficit could be made up through intensive catch-up classes, some of it will remain throughout the affected individuals’ lives. Economically, this means lower career earnings, and hence increasing inequality within society. In aggregate, this educational deficit will also result in a less competitive workforce on the global stage.

Faced with these disastrous consequences, the government should urgently make education, and therefore keeping schools open, its first priority in the management of the pandemic. The UN estimates that in April 2020, 1.6bn children were furloughed from school, due to measures that were taken essentially to protect the lives of their elders.[8] Now that the adult population is better protected through vaccinations, it is time to redress the balance and ensure that children get every chance they deserve to learn and develop.

Achieving this will require more than just lifting the decrees keeping schools closed. Many parents are keeping their children at home out of fear they might get infected and spread it further to the family. Intensive and targeted communication to rationalise that fear is therefore also necessary. This is another reason to proceed quickly with children’s vaccinations, so that the risk of Covid to themselves and their parents and grandparents is reduced. In this situation, rather than “give parents what they want”, so to speak, and close the schools, the government must act as a leader, explain the high benefits and low risks of keeping schools open, and ensure that closures are only ever imposed as a measure of last resort.

The economy: In the clear?

Economically, a consensus emerged early in the pandemic that there is no trade-off between controlling infections and economic growth[9], contrary to what some political debate may have led us to believe. Rising infections inevitably lead to changing behaviour, and this has economic consequences. Conversely, as was clear from the start, fixing the economy implies controlling the pandemic. That meant that the most important policy recommendation a year ago was to get the FTTIS approach right, and the rest would follow.

In the end, it was the vaccination drive that ended up taking the sting out of the pandemic. The impact on the economy was easy to spot, too: the IMF revised GDP forecasts for all countries, and upward revisions (i.e. higher growth) correlate with the level of vaccination.[10] Countries where vaccination rates are in excess of 80% saw an upward revision of more than 0.6% on average. For Malaysia, the most recent estimates[11] from the IMF are 3.1% GDP growth over 2021, increasing to 5.75% for 2022. This reflects both the (negative) impact of the severe wave of infections and associated restrictions in 2021, as well as the good starting position for 2022, notably in terms of vaccination coverage.

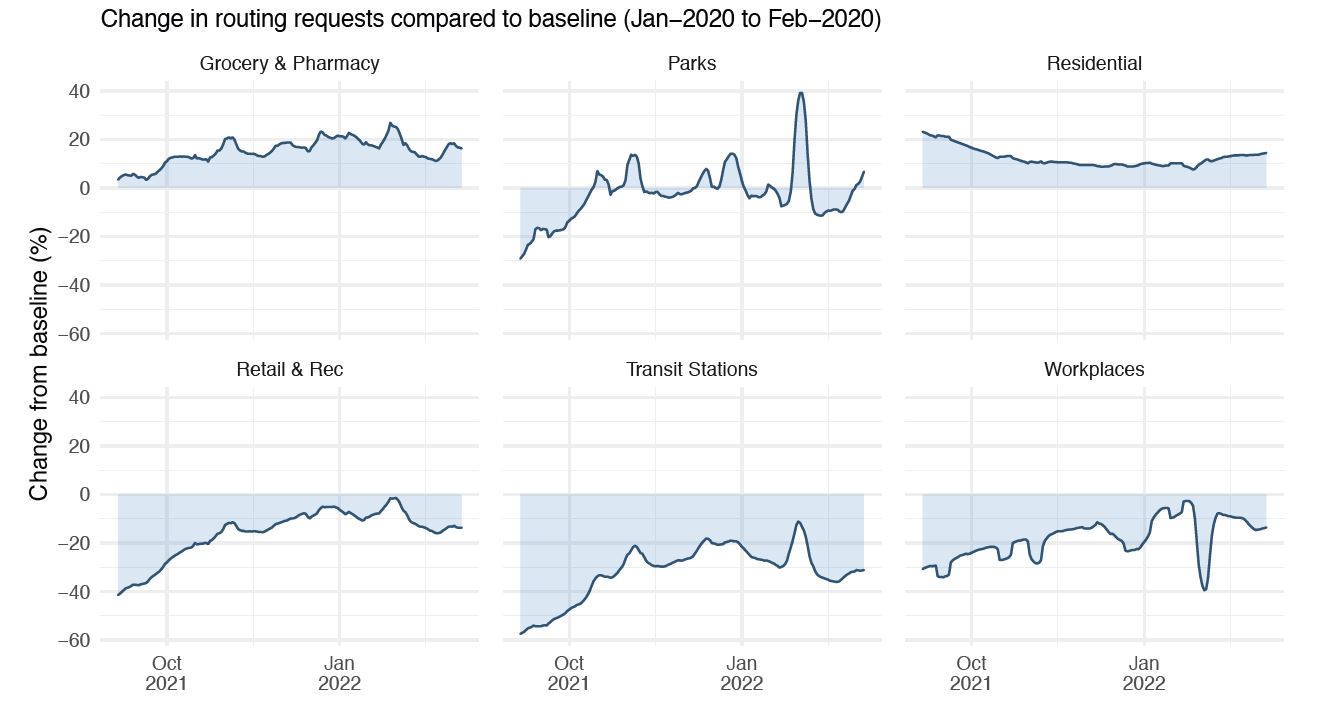

Leading indicators such as mobility statistics (Figure 5) also point to higher economic activity, despite a small blip presumably caused by the Omicron wave. Before the Omicron wave, routing requests to “Retail & Recreation” outlets were almost back at the pre-pandemic level, and this even applied to transit stations. If the Omicron wave in Malaysia develops similarly to other countries, the recent dip in both categories should be short lived.

Figure 5: Routing requests to most destinations remain below baseline

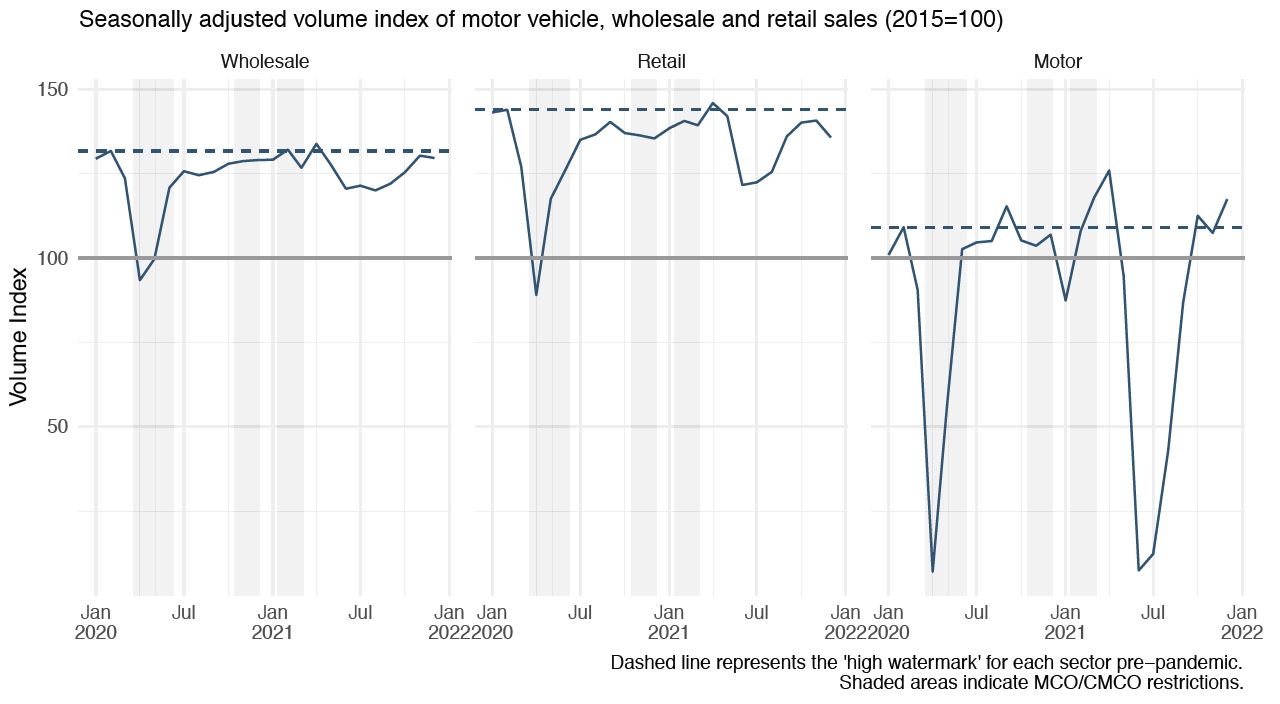

The retail sector, up until December 2021 at least, also seems to have made up most of the lost ground since the start of the pandemic, as Figure 6 indicates.

Figure 6: Retail sales show an uneven trajectory

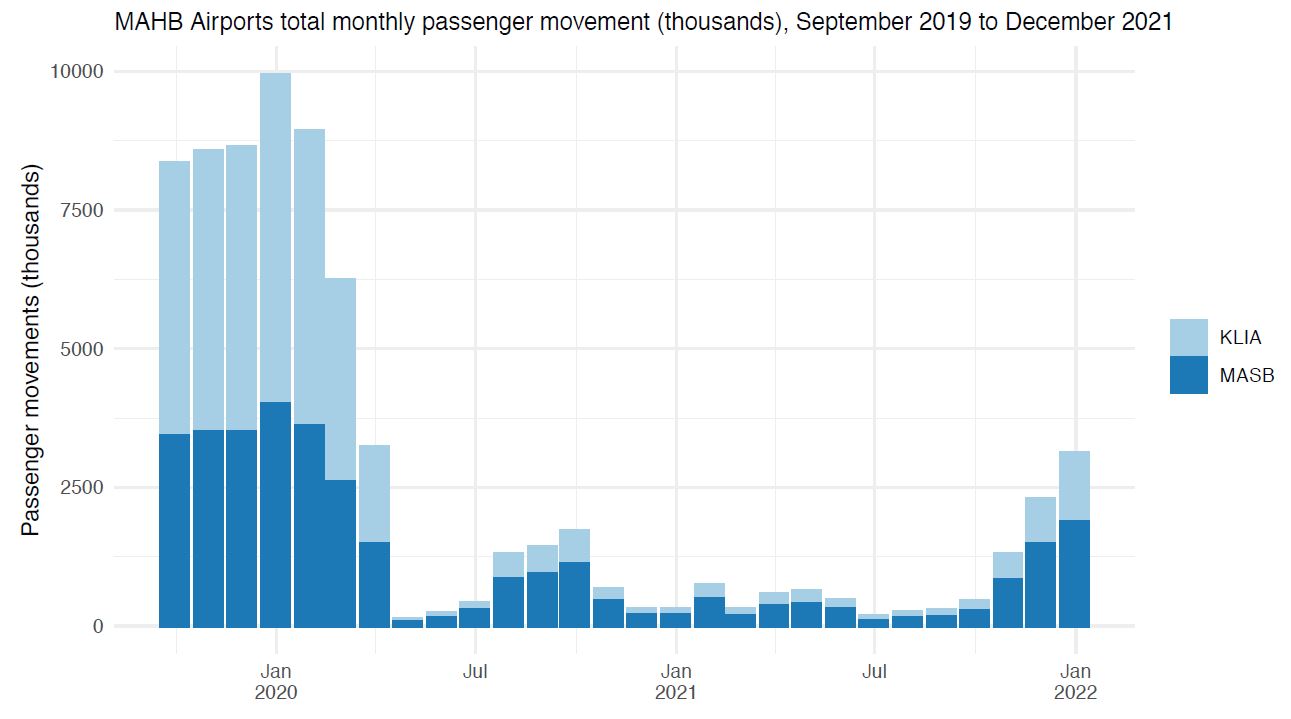

That does not mean that all is well with the economy, however. Not all restrictions have been lifted, in particular those on travel, and, unsurprisingly, passenger traffic at MAHB airports (Figure 7) is still far below its pre-pandemic highs. By extension, the whole travel and tourism sector is inevitably still suffering, and adjacent sectors such as retail, F&B, events etc. are not back to their previous levels.

Figure 7: Total passenger movements are still far below pre-pandemic levels

This illustrates well where we find ourselves today. While certain sectors in the economy are growing robustly, others are still badly affected and in need of support.

Of course, the buoyant economy is not only the result of the pandemic easing, but also of the support measures enacted by governments around the world. It is clear that these measures generally had the intended effect, and with hindsight, we can now also distinguish the most effective policy mix.[12]

For instance, one important dimension turned out to be whether support measures targeted businesses (to maintain cash flow) or consumers (to stimulate demand.) The former generally seemed to work better, maybe because the effect of demand-supporting measures was dampened by limited opportunities to consume, owing to lockdowns and other measures. These are relevant findings to factor into the ongoing support measures that are still required, not least to ensure the most efficient application of public funds.

Risk of overheating?

In summary, the economic news is generally rosy. In fact, compared to early 2021 when we were worrying about downside risks to growth, many observers are now concerned that the global economy is overheating. The ultra-loose monetary policy pursued by central banks, especially in the West, combined with large fiscal injections from governments, could be causing a worrying rise in inflation. So far this dynamic does not seem to significantly affect Malaysia though, with inflation moderating in the first month of 2022. Overall, the level is near the long-term average.

Moreover, it is not yet a closed debate whether the global inflation is general, or due to specific circumstances exacerbated by the pandemic. For instance, bottlenecks in the US ripple through global freight transportation networks[13], leading to higher costs and limiting the availability of goods, both factors that would cause prices for consumers to rise. The expectation is that these bottlenecks will subside eventually, and prices return to normal.

The recent invasion of Ukraine by Russia muddies the waters even further. The spike in uncertainty has triggered a “flight to quality” reflex, for example toward the US dollar, the appreciation of which risks making imports into Malaysia more expensive. The price of petrol has also spiked. With Western countries debating severe sanctions against Russia, the global economy may experience more shocks, the effects of which are hard to map at the moment. Central banks around the world are thus in a difficult position. If they tighten their monetary policy, by raising rates or reducing their bond purchases, to bring inflation under control, economic growth could take a hit, jeopardising the recovery from the pandemic. But conversely, if they do not do anything, we could end up with both low growth (caused by external factors such as geopolitical uncertainty) and high inflation, reminiscent of the “stagflation” of the 1970s. These developments complicate policymaking in the near future even further.

Preparing for the future

With this increase in uncertainty on account of a geopolitical crisis, it is imperative to remove uncertainty on account of the pandemic and provide more predictability to economic actors. Until now, measures to contain the pandemic practically emerged by accident. They had a high degree of uncertainty, were inconsistent, and had the potential to cause an economic shock upon being announced. This has been illustrated again recently, with the population on tenterhooks ahead of a recent NRC meeting and health ministry announcements, related to the rising cases due to the Omicron variant.

But now that we understand the dynamics and impact of the pandemic better, it is possible and arguably necessary to set up a “barometer” of sorts, that will trigger pre-defined measures depending on several transparent criteria[14], such as hospital and ICU admission rate, deaths etc. By publishing this barometer and being transparent about the data, businesses and consumers can plan more accurately. For example, the barometer could define that beyond 60% of ICU beds occupied, workers can only come into the office once a week. Businesses can then define contingency plans for remote working, rota systems etc. ahead of time, rather than having to scramble when the announcement is made. This will be useful not just for Covid-19 but also for the inevitable next pandemic.

Defining predictable measures is one thing, ensuring they are broadly complied with is another. In this respect, trust in government leads to higher compliance and hence lower Covid infection rates.[15] Malaysia fared relatively well on this aspect[16], especially as far as vaccinations are concerned. Consolidating this high level of trust through good governance and transparency is essential, both to manage the endgame of this pandemic, and to deal with future ones.

Short-term support

Beyond this, many of the existing economic support measures should remain in place, albeit more narrowly targeted to those sectors still suffering from the pandemic, in particular travel and tourism, events, and the cultural sector. Interventions on the labour market have proved successful at maintaining a steady level of employment, some systems more so than others (short-time work versus wage subsidies, for example). In addition to this, active labour market policies, such as retraining, are also needed to help workers in sectors that may have been permanently affected.

On balance, the various support programmes enacted throughout the pandemic helped in maintaining individuals’ incomes, and were a much-needed safety net, especially given the nature of Malaysia’s economy. With a large share of workers in the informal sector and already high levels of inequality, the pandemic was poised to have a disproportionate impact on these vulnerable groups. The challenge now becomes to institutionalise at least part of these ad-hoc measures, such as through the Employment Insurance Scheme (EIS), and develop a more comprehensive social welfare system.

Even better than providing social support is to get all sectors in the economy working again of course, and this should be a priority now too. With borders reopening to international travel, prospects for the travel and tourism sectors should start to look up, but it will take time for them to return to their level of activity from before the pandemic. The government should consider creative initiatives to hasten this return to form, for example by organising cultural and sporting events likely to attract international travellers.

Increase our resilience

At this stage, policy interventions should not just be focused on the short term, but also start to address structural issues. The Covid pandemic could be seen as the first big crisis of the “anthropocene”, the most recent period in our history, where human activity started to have a significant impact on the planet and its ecosystems. The next crisis already looms, in the form of disruptive climate change. Just as for the pandemic, our political, social and cultural systems are proving incapable of addressing this crisis decisively. And again just as for the pandemic, the solution will most likely have to be “techno-scientifi”. This means the development of new technology that allows us to move away from polluting fossil fuels for power generation and transportation, and investments in environmental infrastructure such as drainage, dams and dykes to contain the worst impacts of climate change. All these imply significant hard infrastructure.

The pandemic also clearly brought out the bottlenecks and deficiencies in our healthcare and social welfare systems. Faced with a rising threat of pandemics and an ageing population, addressing these through rising investment in soft infrastructure also becomes urgent.

The shifting role of the state and public finance

The unusually large and swift support provided by the state in the aftermath of the economic shock, buttressed by activist central banks at least in the West, has prompted questions on—if not a re-examination of—the role of the state. It is legitimate to ask why the vast sums of money deployed during the pandemic could not also be deployed to address climate change or poverty, for example.

This is especially so given that international institutions such as the IMF and World Bank, who would previously have argued in favour of austerity, endorsed this course of action, even for developing countries. In the event, public finances held up well, despite rising debt levels. Asian countries in particular have developed an idiosyncratic set of policy tools that enabled them to raise their expenditure without experiencing foreign currency crises, which worked very well in this crisis.[17] As an example, the yield on 10-year Malaysian government securities rose by less than 30 basis points over the whole period of the pandemic to date, despite an increase in the debt to GDP ratio of some 10% over the same period.

These developments have raised the expectations that we could see the return of (neo-) Keynesian policies, with the state playing a more preponderant role in the economy. While it is probably too early to make that conclusion, there certainly is no lack of investments where the state’s involvement would be welcome, as highlighted earlier.

The role of the state was not reassessed only from a financial standpoint. It was also instrumental in the extraordinarily fast development of the Covid vaccines, demonstrating the value that public/private collaboration can have for innovation. Crucially, the state’s input was not limited to financial support or granting dispensation to the normal regulations. It also provided scientific and organisational advice to the private companies developing the vaccines.[18] This model squarely fits in a so-called mission-oriented approach to development, which would also prove very effective in addressing climate change. Governments at every level (state and federal) should start aligning their development policies to this mission-oriented approach.

Shifts in the international order

Lastly, the pandemic also seems to have accelerated the transition to a new multipolar world, in large part thanks to China’s success in controlling the pandemic and maintaining a “zero Covid” policy to this day. The comparably dismal performance of Western countries not only has theoretical repercussions for the appeal of both models of government, but also practical implications.

Most Western countries now seem to have reached a point where living with Covid is possible, albeit at great cost in terms of lives lost. China’s insistence on maintaining zero Covid, on the other hand, is still liable to cause severe economic disruption at times. This makes the management of global supply chains very difficult presently, especially given how reliant they are on China. Affected manufacturing companies are therefore scrambling to diversify where they can.

Global shipping has also been severely affected by the pandemic. Today, cargo ships tend to follow a “bus” model, whereby one ship goes from one port to the other. Any delays at each port therefore tend to compound, causing very significant delays at the end of the chain. Shipping companies are now experimenting with a “hub and spoke” model[19], where larger ships only dock at a few large ports, and smaller ships service smaller ports.

These are just two small examples of the direct impact businesses may see, but it is imperative for Malaysia to respond to these trends and capitalise on them. They present new opportunities, for example to attract new high value-added manufacturing industries, or to consolidate the importance of Port Klang in global shipping routes.

Conclusion

The Covid-19 pandemic took the world by surprise and forced us to urgently reckon with our collective weaknesses and blind spots. Conventional wisdom on how to organise our health, economic and social affairs was upended, and it seems like a shift to a new model is now underway, even if we do not quite know what it is yet. Inevitably, this goes paired with a high degree of uncertainty and risks at every level, from the type of geopolitical risk that we are witnessing now in Ukraine, to the next crisis of the “anthropocene”.

We were lucky that this pandemic turned out to be altogether relatively mild. The next one might not be, and witnessing the disruption Covid caused around the world, we need to remedy the issues that were exposed urgently. At the same time, risks usually come paired with opportunity, and here policymakers should do all they can to capitalise on them and build Malaysia back better.

The major difference this year compared to last year is that we now seem to have found an effective tool to control the pandemic, in the form of vaccines. This allows us to gradually start focusing elsewhere and propose ways to address many of the issues and weaknesses exposed by the pandemic.

For list of references and appendix, kindly download the document to view.

Editor: Ooi Kee Beng

Editorial Team: Sheryl Teoh, Alexander Fernandez and Nur Fitriah (Designer)

[1] Cookson & Telling, 2022

[2] Our World in Data, 2022

[3] Milne 2022

[4] Pueyo 2022

[5] Mancini 2022

[6] Ahuja 2022

[7] Agostinelli e.a. 2022

[8] Tooze 2021

[9] Giles 2022

[10] Wolf 2022

[11] IMF 2022

[12] Deb e.a. 2022

[13] Dempsey 2022

[14] Sandhu 2022

[15] Kuchler 2022

[16] CodeBlue 2022

[17] Tooze 2021

[18] ibid

[19] Dempsey 2022

You might also like:

![Strengthening Malaysia’s Private Higher Education Sector through a Structural Revamp]()

Strengthening Malaysia’s Private Higher Education Sector through a Structural Revamp

![Interracial Marriages Getting Popular in Malaysia: Government Support Would be Welcomed]()

Interracial Marriages Getting Popular in Malaysia: Government Support Would be Welcomed

![Lessons from Southeast Asia's Responses to Covid-19]()

Lessons from Southeast Asia's Responses to Covid-19

![George Town Heritage Celebrations: Achievements and Reflections]()

George Town Heritage Celebrations: Achievements and Reflections

![Key Measures Identified for Strengthening STEM Interest among Students in Penang]()

Key Measures Identified for Strengthening STEM Interest among Students in Penang