EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Malaysia’s national target of 30% women representation in politics has yet to be realised,despite clear national policy commitments established since 2009. Women parliamentarians proportion currently stands at only 13.5% and state assemblypersons at a mere 12.0%.

- Candidacy is identified as the bottleneck; election data for the last two elections shows that the percentage of women candidates didn’t even reach 20% (in GE15: parliament candidacy: 13.4%, state assembly candidacy: 13.3%). No individual coalition or party has managed to nominate at least 30% women, signifying that the gap already exists beforepolling day.

- Systemic barriers such as patriarchal sociocultural expectations, male-dominated candidate selection committees and refusal of male incumbents to rotate their seats limit women’s opportunities as candidates. This is further entrenched by a limited access to party resources and networks.

- The implementation of a minimum 30% women candidates target is vital in achieving national gender equality agendas. Having more women leaders will create diversity in policy making and advocacy for inclusive governance, in addition to encouraging the civic and political participation of women.

- Concrete steps must be taken to realise this target. This includes mandating parties to formally adopt the minimum 30% target and including women leaders with equal authority on selection committees. Equitable access to financial resources must be provided, and aspiring women leaders must be mentored to build their political capacity.

- Coalitions – where seat bargaining takes place

- Parties – where the leadership and selection committee decides who will stand as candidates

The sections that follow will use nomination trends for coalitions and parties in the last two elections to provide a clear picture of the gaps in nomination. The analysis considers the barriers to nomination, and why a minimum 30% women candidates is vital. Practical steps need to be taken so that the candidacy barriers can gradually be overcome, and thereby meet the targets for women’s political representation. This is crucial for achieving genuine and equitable political empowerment.

Candidacy trends of the last two elections

In the most recent federal election held in 2022 (GE15), the total percentage of women candidates stood at 13.4%. Though it was a 2.5 percentage point improvement from the 2018 elections (GE14),the stark reality is that candidacy is still well under half of the 30% benchmark.

The state elections show a comparable trend. Totalling all the state elections held between 2020 to 2023 – Sabah (2020), Melaka (2021), Johor (2022), the three states which held their elections concurrently with the federal election (Perlis, Perak, Pahang) and the six states that chose to go to the pools in 2023 (Kedah, Penang, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Kelantan, Terengganu) – women made up 13.3% of all candidates, a slight increase of 2.5 percentage points from 2018’s 10.8%.

In Sarawak’s state elections2, women’s candidacy declined from 12.3% in 2016 to 9.7% in 2021 – though the entry of Parti Sarawak Bersatu (PSB) and Party Bumi Kenyalang (PBK) in the later election may have played a role. These parties predominantly fielded male candidates, which likely resulted in the lower overall share of female candidates in 2021.

The question we need to ask is, where are the candidacy gaps in the nomination pipeline? As established earlier, the process has two distinct layers. Seat allocations are usually negotiated at coalition level; parties will then choose their candidates via internal selection committees. By disaggregating the nomination data along coalition and party lines, the source of these persistent gender gaps can then be better analysed.

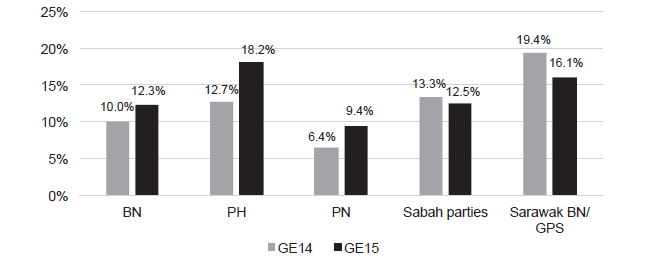

Women parliamentary candidates of all coalitions/blocs in GE14 and GE15 were all under 20%; highest share was Sarawak BN in GE14.

Figure 1:1 Percentage of female candidates in GE14 and GE15, federal elections, by coalition/region bloc

Source: Data collated from the Election Commission of Malaysia, Tindak Malaysia, author’s own calculationsNote: BN/PH/PN = federal coalitions; GPS = Sarawak coalition; “Sabah parties” = Sabah-based parties (Warisan, UPKO, PBS). West-Malaysian parties contesting in Sabah are counted under their coalitions. Coalition membership is as per election cycle (e.g., Bersatu: PH in GE14, PN in GE15). See Appendix A for acronyms

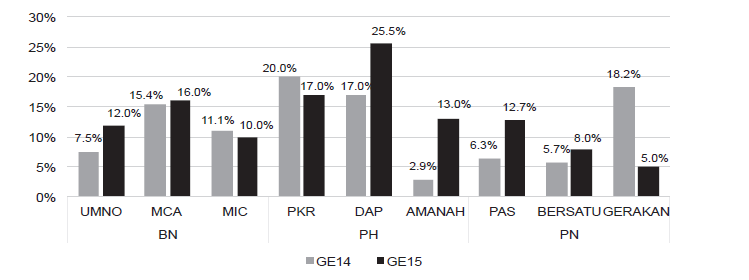

Women’s candidacy stayed below 30%; most Peninsular parties did not surpass 15%

Figure 1:2 Percentage of female candidates in GE14 and GE15, by Peninsular-Malaysia based parties

Source: Data collated from the Election Commission of Malaysia, Tindak Malaysia, author’s own calculationsA party-analysis in Figure 1.2 shows that approximately half of the Peninsular-Malaysia based parties saw an increase in their number of women parliamentary candidates for GE15. Amanah showed the largest increase of 11.1 p.p. to 13%, but they also had the lower base of 2.9% in GE14. DAP achieved the highest percentage of women candidates for GE15 (25.5%, +8.5p.p.). However, PKR, which led PH in women candidates in GE14. noted a deduction of 3.0 p.p. to 17.0%. Component parties in PN saw a modest increase (PAS: +6.4 p.p., Bersatu: +2.3%) with the exception of Gerakan – who fell sharply from 18.2% to 5.0% (-13.2 p.p.). For BN parties, UMNO recorded an increase of 4.5% while MCA and MIC more or less kept to their GE14 percentage.

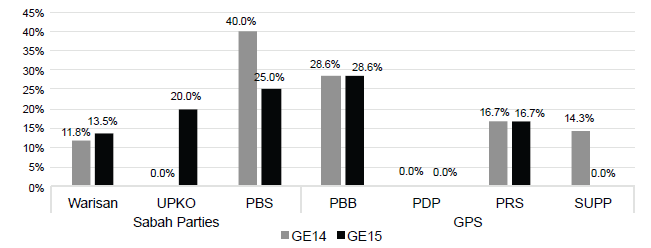

PBB lead in women nominees, other Bornean parties show more erratic patterns

Figure 1:3 Percentage of female candidates in GE14 and GE15, by Bornean based parties

Source: Data collated from the Election Commission of Malaysia, Tindak Malaysia, author’s own calculationsNote: For comparability, this figure includes only parties that fielded candidates in both GE14 and GE15, parties contesting only one cycle are omitted here (but included in aggregate totals for coalitions/regional blocs)

In East Malaysia, PBB was the only party with a share of women parliamentary candidates close to 30%, maintaining a steady 28.6% (Figure 1.3). Although Sabah’s PBS marked 40% in GE14, the party also had a significantly smaller base of candidates. Small allocations can skew results: a single woman nominee can vastly affect the percentages. Conversely, smaller parties also tend not to nominate women candidates, as in the case of PDP (for both cycles) and SUPP in GE15. Meanwhile,Warisan recorded an increase of 1.7% p.p. in GE15 to 13.5%, while PRS’s share of women candidates remained unchanged at 16.7%.

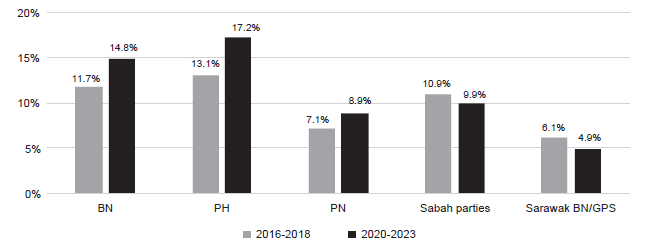

No coalitions or regional blocs exceeded 20% women candidates for state elections; PH was highest at 17.2% in the 2020–2023 window

Figure 1:4 Percentage of female candidates in GE14 and GE15, state elections, by coalition/region bloc

Source: Data collated from the Election Commission of Malaysia, Tindak Malaysia, author’s own calculationsNote: Non-synchronous state elections are pooled: 2016-2018 includes Sarawak 2016 state elections; 2020-2023 includes Sabah (2020), Melaka (2021), Sarawak (2021) Johor (2022), Perlis, Pahang, Perak(2022), Kedah, Penang, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Kelantan, Terengganu. Also see Figure 1.1 for caveats.

Across state elections, no coalition or bloc managed to surpass 20% women candidates. The Peninsular coalitions saw modest gains, with PH recording the highest increase, rising from 13.1% to 17.2% in the 2020–2023 period. BN followed with an increase of 3.1 p.p. to 14.8%, while PAS also raised its number of women candidates (8.9%, +1.8%). Conversely, the Borneo blocs moved in the opposite direction: women candidates for the Sabah bloc decreased by 1.0 p.p. while GPS’ share

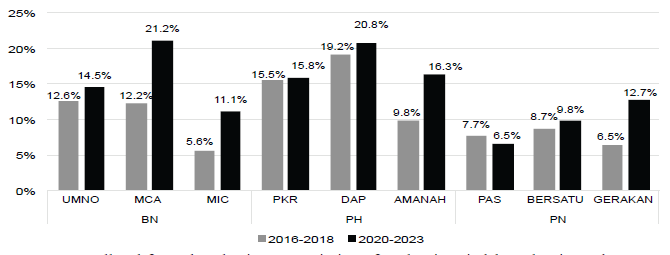

declined by 1.2 p.p.All parties except PAS recorded increase in share of women candidates; MCA’s share is the highest

Figure 1:5 Percentage of women candidates in last two cycles of state elections, by Peninsular-Malaysia based parties

Source: Data collated from the Election Commission of Malaysia, Tindak Malaysia, author’s own calculationsNote: MCA and MIC did not participate in the 2023 state elections

Across Peninsular parties, no single party reached the 30% mark, though several parties showed improvement (Figure 1.5). MCA was the biggest mover, rising from 12.2% to 21.2% (+9.0 p.p.). Their coalition members also increased their shares: UMNO rose from 12.6% to 14.5%, and MIC saw an increase of 5.5 p.p. to 11.1%. DAP was the best performer for PH with 20.8% (+ 1.6 p.p.), but Amanah’s gains were bigger (+6.5 p.p. to 16.3%). For PN, Gerakan (+6.2 p.p. to 12.7%) and Bersatu(+1.1 p.p. to 9.8%) also saw gains. Conversely, PAS has the lowest percentage in the 2020-2023cycle, at 6.5% (-1.2 p.p.).

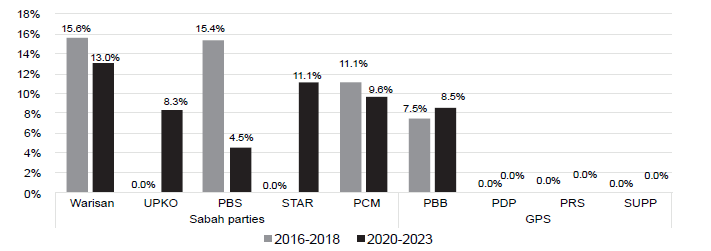

No Bornean-based parties managed to hit even the 20% floor; women representation of Sarawak parties especially low

Figure 1:6 Percentage of women candidates in last two cycles of state elections, by Borneo-based parties

Source: Data collated from the Election Commission of Malaysia, Tindak Malaysia, author’s own calculationsNote: please see Figure 1.3 for caveats

In East Malaysia, Figure 1.6 shows that UPKO (+ 8.3 p.p) and STAR (+11.1 p.p) made significant gains on paper – but this must be viewed in the context of a smaller pool of candidates, where one woman nominee would hugely move the goalpost. The same is applied to PBS, where the 10.9 p.p. decline was the result of one less woman candidate. Meanwhile, parties who fielded candidates in most seats saw their women’s share decreasing. Warisan dropped from 15.6% to 13% while PCM fell

by 1.5 p.p to 9.6%. In Sarawak, PBB increased women candidates by 1.0 p.p while their coalition partners (PDP, PRS, SUPP) consistently failed to field any female candidates across both cycles.Barriers to nomination

As the data clearly shows, the gaps in nomination apply to both coalitions and parties. Neither coalition nor party managed to achieve 30% women candidates, and even those reaching the 20% threshold were infrequent. It is clear that the roadblock to minimum 30% women’s representation in politics stems from candidacy itself. Simply put, there are too few women nominated to run. An d given that not every nominee will win a seat, overall representation can realistically never exceed the low share of women candidates on the ballot.

There are several systemic barriers that contribute to this bottleneck at the candidacy level:

Patriarchal culture and gendered sociocultural expectations

Women’s place is still largely confined to the private sphere, and not in public life. They are expected to prioritise family and domestic responsibilities, effectively discouraging professional and leadership ambitions (Aminuddin & Azlan, 2024). Women are also often subjected to gender stereotyping that questions their abilities as leaders – as being too “emotional” and not having what it takes to make hard decisions. Unlike men, women aspiring to a political career often face an extra hurdle: needing permission and approval from their husbands and families (Saidon, 2019). This pervasive notion is more often than not institutionalised by party leaders, and limits women’s participation on the ballot.

Male domination and gatekeeping in candidate selection

Key decision-making in Malaysian politics is male-dominated; this is evident in coalition bargaining for seat allocation, mostly conducted by male leaders, and internal candidate selection, where committees are typically chaired by men. These male gatekeepers are a significant hindrance as theyare likely to select candidates that most resemble themselves – which would first and foremost be men (Cheng & Tavits, 2011). Women’s wings are largely relegated to support roles; endorsements would still travel through the male-dominated network (Weiss, 2013). Hence, male dominance among party gatekeepers privileges men over potentially more qualified women, as candidate shortlists are highly centralised and often assembled through male-dominated networks of party elites (Mohamad, 2018; Ahmad Zakuan, 2023). This systematically disadvantages women, as they would have lost out even before the ballots are printed.

Structural preference for male incumbents

The issue of male incumbency is another barrier to women’s candidacy. The current First-Past-the-Post (FPTP) system often results in a high retention rate, creating an incumbency advantage, where incumbents are often male (Schwindt-Bayer, 2005). When male incumbents refuse to give up their seats, this limits the

number of available seats for newcomers. Party elites, in prioritising the reinforcement of patronage ties over gender parity, will inevitably favour the male incumbent in candidate selection (Mohamad, 2018).This resistance further blocks the candidacy of women.Party gatekeepers often try to justify the incumbency (and candidacy) bias by claiming women are less winnable, but empirical data from GE14 show that women were equally competitive in mixed-gender seats (Yeong, 2018). Ultimately, the structural preference of retaining male incumbents closes the gate to aspiring women, preventing their participation.

Resource constraints and financial gatekeeping

The constraint of resources is an additional obstacle for women aspiring to run. The corporate, political networks within parties are control by male leaders, and they have the final say on the allocation of party resources and central campaign funds, which are mostly given to established men (Saidon, 2019). Women are effectively shut out, unless they show the ability to finance a potential campaign on their own merits. Additionally, women are also side-lined in non-monetary resources such as mentorship and training programmes. While men have full access to these resources, the political elites are less willing to afford the same to women (Wan Ismail, 2002). Hence, the monopolisation of resources by male leaders then further contributes to the gatekeeping of women’s entry.

The case for minimum 30% women candidates

The preceding analysis further confirms that the gaps are significant before polling day; with women facing daunting challenges during the nomination process. The target of minimum 30% women candidates is therefore a normatively fair and operationally measurable floor, and well-aligned with the country’s existing 30% gender commitment. It aims to establish a fairer baseline and signifies the importance of women’s political participation in Malaysia.

Why is the minimum 30% floor important? Key reasons include:

Honouring the 30% mandate

As it stands, women are 47.5% of the country’s total population and yet, their representation in government falls significantly short of even the one-third mark. Since 2009, Malaysia has made a commitment to instil at least 30% women representation in politics. Pushing for 30% women candidates is a crucial step taken towards the target of equal representation. Ensuring gender balancein politics is a fundamental principle of fairness – women deserve an equal voice in shaping policies and making decisions that affect society as a whole. Setting a candidacy floor is an operationally viable mechanism that converts a long overdue policy target into action.

More diversity in policy making and better governance outcomes

Studies have presented evidence that more women elected to government correlates with a bigger emphasis on policymaking that prioritises the needs of women, minorities and the marginalised(Asiedu et. al., 2018). Women leaders bring different perspectives to address issues that are often overlooked in policymaking, and they are more vocal in pushing for policies that commit to women’s issues and rights. This is demonstrated in the passing of crucial legislation such as the Anti SexualHarassment Act 2020, where a contingent of bipartisan women politicians, along with women activists, was instrumental to its success (BERNAMA, 2022).

Furthermore, greater women participation in governance often advocates for more accountability and transparency in leadership (Ng, 2010). The 30% candidacy floor is therefore an important mechanism that necessitates the increase of women on the ballot, and ensures that more women are selected to achieve the representation needed for better governance and stronger policy outcomes.

Encouraging civic and political participation of women

The lack of female role models in politics is one of the deterrents for women’s political involvement.There needs to be more spaces created for women to increase their civic and political participation,and a 30% candidate floor is one of the most vital means in achieving this. Selecting women as candidates grants them more visibility on the ground, as they are then able to engage with the constituents and present their policy ideas. An increase of women candidates creates a positive ripple effect where more women will feel inspired to run for office, hence creating a pool of viable women candidates for the future (Aminuddin & Azlan, 2024).

With more women on the ballot – and eventually in office – the message is clear: politics is not a male-dominated space and women’s voices are valuable. Ensuring 30% women candidates helps to increase women’s exposure and normalise women’s leadership, ensuring that every election cycle is an opportunity for women’s representation to grow.

The way forward: securing the future of women’s representation

Having descriptive and substantive representation of women in government is a foundational principle of democracy and good governance, and committing to 30% women candidates will be a start to it. Data from recent election cycles show that we are still far from achieving this. Hence, we need to think about how to realistically close the gaps by taking viable action. Political parties have a responsibility to play, as they are the primary gatekeepers to power. Therefore, achieving the 30% commitment requires focus on the following key areas:

Formal commitment by parties to nominate at least 30% women candidates

Parties have been voicing their commitment towards 30% women as candidates without seeing actual delivery or results, as the data have clearly shown. In advancing national gender equality agendas, political parties should formally adopt a minimum 30% target for women on their nomination lists for future elections. This ensures that qualified and capable women have a more equal chance to compete for the opportunity to serve the electorate. By formally committing to the 30% target, parties, demonstrate integrity by living up to their promises of 30%, ensuring candidate diversity that includes the voices and representation of women. As parties have all the power in candidate nomination, officially adopting this 30% policy into the party constitution is the strongest way towards actualising

the target.Inclusion of women leaders on candidate selection committees

The candidate selection committee is the gatekeeper and the decision maker of who gets on the list. To ensure fairness and representation, it is a necessity to include women leaders on candidate selection committees, and they must be given equal power in voting decisions. Women leaders are more likely to seek out and advocate for other qualified women candidates, pushing for their selectionas candidates (Cheng & Tavits, 2011; Ahmad Zakuan, 2023). Their presence will counteract and balance any inherent bias held by male gatekeepers, paving the way for women candidates and forming a candidate list that is more reflective of the electorate they serve. By giving women leaders equal decision-making authority within the selection process, parties demonstrate their accountability and commitment to achieving the 30% women target.

Ensuring equal access to financial resources

To rectify the systemic disadvantages of women in accessing traditional financial networks within the parties, parties must ensure that women have equitable access to these resources. Having equal accessto financial resources increases the viability of women as candidates. These resources allow prospective women to build their networks and fund early polling to demonstrate electability to party leaders.Additionally, providing seed funding for initial outreach and ensuring financial support for campaign upon formal nomination is equally important. Women candidates must be afforded the same pool of financial resources as with the men, with the same criteria applied. All candidates must have the same amount of support. Equitable and transparent access to financial mechanisms are essential in building the pipeline of women candidates

Political capacity building and mentorship for women

The exclusion of women from networks (both formal and informal) enjoyed by men through the “oldboys’ club” acts to restrict their access to mentorship and recruitment opportunities, which are vital for candidacy approval. Mentorship and guidance must be provided to aspiring women candidates, helping them build internal alliances and strengthening their capacity. This acts to equip women with the political capacity and knowledge needed to earn the endorsement they deserved.Some political parties, for example DAP’s HERLEAD and PKR’s SWAN, have established official training programmes targeting women, and this can be a model that can be replicated and scaled up for other political parties. Seasoned politicians, both men and women, should establish themselves as mentors, for the strategic purpose of building a strong candidate pipeline that includes strong women representation, ensuring that women are equipped with the tools and knowledge to rise as candidates.

Conclusion

To effectively achieve the minimum 30% representation of women in Malaysia’s political sphere begins with the candidate list. The persistent gap in candidacy is a structural challenge as women cannot be elected if they are not nominated to stand. Moving forward, comprehensive reforms that fights for the inclusion of women as candidates will demonstrate commitment towards gender equality in all spaces of life. Institutionalising a 30% women candidacy target is an important step towards a truly representative democracy.

References

Ahmad Zakuan, U. A. (2023). Challenges for women in political parties in Malaysia and acceleration strategies to leadership in politics. KAS Malaysia.

Aminuddin, N. T. M. & Azlan, S.N. (2024). Breaking Barriers and Shaping Futures: Analysing Young Women’s Leadership and Candidacy in Malaysia’s Political Landscape. International Journal of Law, Government and Communication, 10 (39), 01-25.

Asiedu, E., Branstette, C., Gaekwad-Babulal, N., & Malokele, N. (2018). The effect of women’s representation in parliament and the passing of gender sensitive policies. In ASSA Annual Meeting (Philadelphia, 5-7 January). https://www. aeaweb. org/conference.

BERNAMA. (July 20, 2022). Dewan Rakyat passes Anti-Sexual Harassment Bill, retrieved fromhttps://www.bernama.com/en/news.php?id=2102178

Cheng, C. and Tavits, M. (2011). Informal influences in selecting female political candidates,Political Research Quarterly, 64(2), 460–471.

Chin Abdullah, M. (2005). Expanding Democracy, Enlarging Women’s Spaces, in B. Martin, A.Cerdeña, J. Barriga and S. Franz (Eds.), in Gaining Ground?: Southeast Asian Women in Politics and Decision-making, Ten Years After Beijing : a Compilation of Five Country Reports. Quebec City:Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

Mohamad, M. (2018). Getting More Women into Politics under One-Party Dominance: Collaboration, Clientelism, and Coalition Building in the Determination of Women’s Representation in Malaysia, Southeast Asian Studies, 7(3), 415-44.

Ng, C. (2010). The Hazy New Dawn. Gender, Technology and Development, 14(3), 313–338.

Saidon, Nor Rafidah. (2019). Leadership and Gender: Women’s Political Participation in Malaysia(1980-2013). 64-73.

Schwindt-Bayer, L. A. (2005). The incumbency disadvantage and women’s election to legislative office. Electoral Studies, 24(4), 565–589.

Wan Ismail, A. (2002). Women in Politics: Reflections from Malaysia. International IDEA, pp.191–202.

Weiss, M. (2013). Coalitions and competition in Malaysia – incremental transformation of a strong-party system, Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 32(2), pp. 19–37.

World Economic Forum (2025). Global Gender Gap Report 2025. https://reports.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2025.pdf

Yeong, P. J. (2018). How Women Matter: Gender Representation in Malaysia’s 14th General Election. The Round Table, 107(6), 771–786.>

References

Appendix: Acronyms

AMANAH: National Trust Party (Parti Amanah Negara)

BERSATU: Malaysian United Indigenous Party (Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia)

BN: National Front (Barisan Nasional)

DAP: Democratic Action Party (Parti Tindakan Demokratik)

GERAKAN: Malaysian People’s Movement Party (Parti Gerakan Rakyat Malaysia)

GPS: Sarawak Parties Alliance (Gabungan Parti Sarawak)

GRS: Sabah People’s Coalition (Gabungan Rakyat Sabah)

PAS: Malaysian Islamic Party (Parti Islam Se-Malaysia)

PBB: United Bumiputera Heritage Party (Parti Pesaka Bumiputera Bersatu)

PBS: United Sabah Party (Parti Bersatu Sabah)

PDP: Progressive Democratic Party (Parti Demokratik Progresif)

PCM: Love Malaysia Party (Love Malaysia Party)

PH: Alliance of Hope (Pakatan Harapan)

PKR: People’s Justice Party (Parti Keadilan Rakyat)

PN: National Alliance (Perikatan Nasional)

PRS: Sarawak Peoples’ Party (Parti Rakyat Sarawak)

MCA: Malaysian Chinese Association (Persatuan Cina Malaysia)

MIC: Malaysian Indian Congress (Kongres India Se-Malaysia)

STAR: Homeland Solidarity Party (Solidariti Tanah Airku)

SUPP: Sarawak United People’s Party (Parti Rakyat Bersatu Sarawak)

UMNO: United Malays National Organisation (Pertubuhan Kebangsaan Melayu Bersatu)

UPKO: United Progressive Kinabalu Organisation (Pertubuhan Kinabalu Progresif Bersatu)

WARISAN: Heritage Party (Parti Warisan)You might also like:

![Towards a Healthier Digital Childhood: Guidelines on Screen Use for Children]()

Towards a Healthier Digital Childhood: Guidelines on Screen Use for Children

![Cold War 2.0 Comes Knocking at ASEAN’s Door: Choices for ASEAN, China, and US]()

Cold War 2.0 Comes Knocking at ASEAN’s Door: Choices for ASEAN, China, and US

![Social Media Usage among Penangites: A Tool of Benefit or Distraction?]()

Social Media Usage among Penangites: A Tool of Benefit or Distraction?

![US-China Trade Relations: Implications for Penang's E&E Industry]()

US-China Trade Relations: Implications for Penang's E&E Industry

![Synergy among Stakeholders is Key to the Sustainability of Cultural Tourism in Penang]()

Synergy among Stakeholders is Key to the Sustainability of Cultural Tourism in Penang

Introduction

As a signatory to the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action and Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), Malaysia has committed itself to advancing equality for women. Specifically, under the 2009 National Policy on Women, Malaysia has adopted a target of at least 30% women’s representation in Parliament, State Legislative Assemblies and the Senate, and this has been reaffirmed in subsequent national development plans. However, women’s political representation remains dismal. Currently, women make up 13.5% of parliamentarians, 12.0% of state assembly members and 20% of senators. In the history of the country’s female political representation, the proportion has never gone higher than 14.4% in Parliament (2018) and 12.3% in state assemblies1 (2023). Globally, Malaysia ranks 128 out of 148 countries in 2025 Global Gender Gap’s sub-index for political empowerment – worst in the region above Brunei Darussalam.

One of the main constraints to representation lies at the nomination stage. The focus here is who makes it onto the ballot. There are two layers to consider: