EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- On 2 January 2024, Malaysia’s government launched PADU, a Central Database Hub for targeted subsidies. Despite low registration and security concerns, PADU aims to improve assistance by centralising income and socio-economic data, ultimately enabling inclusive targeting.

- Beyond enabling a data-informed subsidy targeting mechanism, PADU could improve inclusive policy-making and increase the effectiveness of long-term welfare planning and poverty alleviation.

- Alas, the current implementation of PADU requires close review due to data security deficiencies in the public sector, the potential misuse of personal data for political gain, and biases, loopholes and leakages from manual registration and self-reporting.

- We recommend that PADU prioritise the integration of existing formal sector databases, design data-gathering approaches for the informal sector and hard-to-reach individuals, and develop clear data-sharing protocols between agencies and departments. This could ensure a comprehensive coverage of individuals with and without existing government records.

- In terms of data reconciliation and outreach, local government, including the village chiefs (MPKK) and state assembly persons (ADUN), can help update individual data and promote PADU registration by virtue of their close ties with the community. Communication channels with MPKK and ADUN have to be established. We should also explore integration options between PADU and existing social programmes.

- To ensure the success of PADU, strong access controls, multi-factor authentication, and regular vulnerability scans are needed. A trustworthy database system must have a clear data governance framework, risk assessment, and transparent communication about data security practices. Continuous monitoring and adaptation are key to staying ahead of evolving threats.

Background

A comprehensive database system governed by the government is an impetus to ensure that the government’s financial assistance, subsidies and social protection are effectively carried out. While the existing cash transfer Rahmah Cash Aid scheme (STR) to low-income households and social protection programmes have covered at least half of Malaysia’s households and adult individuals, the government seeks to establish a comprehensive database to enable an inclusive subsidy targeting mechanism.

The Central Database Hub or Pangkalan Data Utama (PADU) is a collaborative initiative by the Ministry of Economy, the Department of Statistics, and the Malaysian Administrative Modernisation and Management Planning Unit (MAMPU) established to solve these data gaps. PADU is a central depository for national household income and socioeconomic data. It contains individual information encompassing address, education, household members, employment, wages, expenditures, and government assistance. It is intended to serve as a central database for rolling out targeted subsidies.

Since its launch on 2 January 2024, the government has encouraged Malaysians to register and key these particulars into the system. Although the number of registrations has increased over time, the number of people who completed the registration process – including submitting a selfie and a snapshot of a national registration identity card (NRIC) – still needs to be improved.

By 7 January 2024, 800,000 Malaysians had registered on the platform. Two weeks later, less than five percent of Malaysians aged 18 and above, or nearly 1.4 million people, had registered.[1]The civil service was then urged to submit their information and data on the system by mid-February.[2] Following this, a spike in registrations was reported at 2.4 million as of 1 February 2024.[3] This number remains low in contrast to the government’s target of 29 million registrations by the end of March.[4]

Since its launch, PADU has surfaced a few critical issues that warrant deeper inquiry. Firstly, data

security breaches and the Personal Data Protection Act remain concerning due to a data security loophole being evidenced within a week of the launch. Secondly, the need for manual registration may affect the reach. Even though the government indicated that PADU consolidates citizen information from existing agencies such as the Employees Provident Fund (KWSP) and STR database by Inland Revenue Board Malaysia (LHDNM), much of the information boxes in the PADU system remains blank and requires input.

This brief addresses the PADU system on these two fronts, assesses alternatives, and provides policy

recommendations for a whole-of-nation database and subsidy targeting mechanism.

Advantages of an effective well-implemented PADU system

The vision for a consolidated socioeconomic repository system brings many benefits.

PADU enables data-informed subsidy targeting

The comprehensive system allows the government to make data-informed decisions on subsidy targeting and poverty reduction. For instance, the expected rollout of the targeted subsidy for RON 95 petrol in the second quarter of 2024 would use the PADU database to identify aid recipients based on individual and disposable household income.[5]

PADU complements existing and upcoming aid targeting

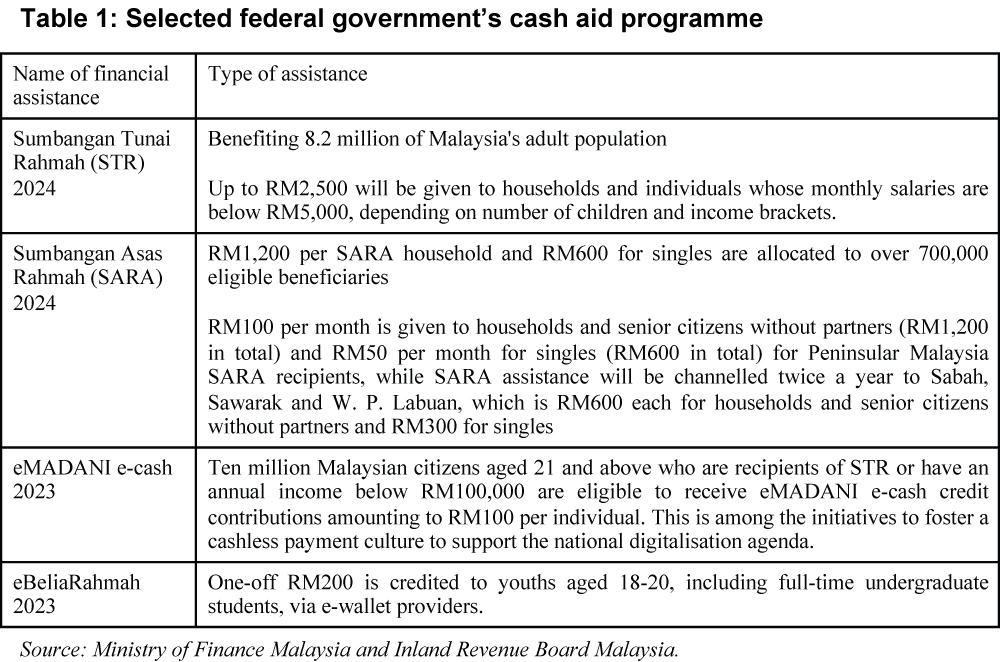

Under Rahmah’s initiative, Sumbangan Tunai Rahmah (STR) is an initiative managed by LHDNM from the Madani Budget. The main objective is to help households and individuals cope with the rising cost of living. In addition to the STR programme, poor and hard-core poor households categorised under the e-kasih programme are given additional assistance through Sumbangan Asas Rahmah (SARA).

Table 1: Selected federal government’s cash aid programme

Source: Ministry of Finance Malaysia and Inland Revenue Board Malaysia.

The database enables a better targeting system that opens up a plethora of possible intricate policies aimed at different groups of individuals. The canonical cash assistance programme, dubbed the Sumbangan Tunai Rahmah (STR), has maintained its own database to channel cash assistance to households and individuals based on income level. The PADU system will be expanded to allow targeted subsidies based on various metrics beyond income, such as age, gender, location, occupation, and educational level.

The database will also be immensely useful in crisis management. For example, in the event of a natural disaster, the system will be able to accurately and swiftly identify affected individuals via the provided address. The system can also be deployed during a health crisis, where extra cash and food aid can be transferred directly to families with affected occupations. This system plays a key role in long-term positive impacts.

PADU aims for inclusivity

One of the important roles of PADU is to ensure that people who are eligible are not left out of

receiving targeted subsidies, assistance, and social protection. This is particularly pertinent for single M40 individuals burdened by the increasing cost of living yet were previously ineligible for many of the government’s assistance programmes.[6] Other potential beneficiaries currently falling into this policy void include informal workers or small business owners with uncertain income.

It is also important to note that PADU can identify assistance and subsidies in urban and rural areas.

Higher costs of living in the city centre may mean that city dwellers receive different rates of aid and subsidies despite making above the threshold of STR required salaries range.

PADU enables policy testbed and long-term policymaking

Having a bird’s eye view of the socioeconomic landscape enables the government to roll out pilot programmes to test the efficiency and efficacy of various developmental strategies. For example, a programme to improve women’s bargaining power in the household via income injection could be tested by directing funds to the targeted recipients, and its efficacy can be assessed by conducting phone surveys with the beneficiaries.

Besides easier targeting mechanisms, the completeness of the database means that the government will stand on top of a mountain of information that could be used to assess and inform long-term policymaking. This shifts the government’s perspective from short-term and reactive policy directives towards long-term and proactive decision-making. In the context of the social security and welfare system, this allows the government to separate chronic aid recipients from temporary ones, which require different follow-up interventions. For instance, those who constantly receive assistance with no discernible increase in income warrant a relook into the person’s job status, skillset, and upward mobility. On the other hand, a temporary recipient may be unlucky and require provisional support to get back on their feet. Effective database use will ensure that the right resource is directed towards the right people at the right time.

Potential drawbacks of the database

While a well-implemented, well-managed, and well-utilised PADU system opens the door for the potential benefits listed above, the current implementation process is mired in inefficiencies, and data security issues.

Data security defection in the public sector

Data security breaches are one of the most pressing concerns. Even before PADU, the public sector had had a poor record of data protection. In 2023, these incidents reached a record high, with the Personal Data Protection Department receiving reports of 130 data breach cases in the first half of the year, a significant surge compared to the mere 30 cases documented for 2022.[7] The Commercial Crime Investigation Department of the federal police also noted a substantial rise in cybercrime cases, escalating from 10,753 in 2018 to 19,175 in 2022.[8] As outlined in the CyberSecurity Malaysia report,

the government sector encountered the largest data breaches, compromising 291.49GB of data in the initial six months of 2023.[9] A rundown of public sector data breaches in 2022 as follows:

Table 2: Examples of breaches in government databases in 2022

Source: Cybersecurity ASEAN [10]

These breaches not only compromise the privacy of individuals but also enable a plethora of crimes,

whether online or offline. As studied by Kroger et al. (2021), the sensitive information obtained by

crime syndicates is used for ransomware, targeted scams, threats of physical violence, identity theft,

sex crime and blackmail.[11]

The lack of a safe and secure government data protection system brings forth the vulnerability of PADU. A day after the launch of PADU, security breaches were reported, in which a loophole within the system allowed third parties to register an account with someone else’s IC number and postal code. The loophole also enabled these third parties to override existing accounts’ passwords using an IC number.[12] The Ministry of Economy has since rectified this.[13] However, it is important to acknowledge that as PADU collects comprehensive and sensitive information ranging from home addresses to household members’ information and wages for all adult individuals in the country, the damage from a data breach would be much greater than what we are currently experiencing.

Potential misuse of personal data for political gain

In addition, the government’s misuse of the data collected is also of concern. Section 3(1) of the

Personal Data Protection Act 2010 (PDPA) places exemptions on government bodies. This means that the government could use the data gathered beyond subsidy targeting and poverty reduction programmes. This makes the PADU system vulnerable to the misuse of government’s data for political gain or election purposes, as happened in the 2018 election, during which Barisan Nasional, the ruling political party at that time, accessed personal data stored in various government’s agencies to gain an edge in the election.[14] While the government’s spokesperson, Fahmi Fadzil, reassured the public that the government would not use the information gathered in PADU for election, the lack of legal framework implies that there is no guarantee that the system will not be misused, whether by the current or a future administration.[15]

Manual registration and self-reporting are prone to bias, loopholes and leakages.

While PADU aims to be inclusive of individuals that currently fall into policy void, for instance,

informal workers or small business owners who did not receive government assistance due to lack of

documentation or lack of knowledge on the various subsidy schemes available and the registration

process required, the need for manual registration and updating ought to subject some of these individuals to remain opaque in the government’s system. The need to manually update the database at a stipulated time is also prone to leakages, as the government may use outdated information for aid distribution.

To top it off, self-reporting is susceptible to biases. Reporting via this manner is prone to understatement of income and over-reporting of expenditures to maximise subsidy gain. Relying on self-reporting alone makes the system vulnerable to leakages, in which aid is channelled to undeserving individuals. There is currently a lack of mechanisms to verify the inputted data and a dearth of procedures to sort out information when inputted data differs from the official record from other agencies and existing databases.

Policy Recommendations: What is, should be, could be done better?

PADU is by far the most plausible way for the government to build a standardised database for subsidies, assistance and social protection. This system could reduce wastage in government spending, avoid duplication, and increase the effectiveness of targeted assistance. This will help fight rising costs of living while closing the income inequality between the poor and the rich. We provide a few suggestions on ways to improve the PADU system.

Database consolidation: integrating existing databases with dynamic data gathering

Data consolidation should be looked at through two lenses. On one end, the government is already

collecting detailed information on individuals for formal purposes from income tax records and government programmes such as housing applications and welfare assistance. On the other end, many

Malaysians who are not tagged into the formal system, such as small business owners, self-employed

individuals, informal workers, the unemployed, homemakers, the elderly, and people with disabilities,

are often not captured in the existing system. PADU should go beyond a standalone system. Hence, in our first recommendation, putting these two pieces together should form the foundation of the PADU system.

The process should first be approached from the formal sectors, that is, looking into integrating the

existing databases. Data consolidation across different government departments and agencies should

be looked at to form a comprehensive database. Existing databases by the KWSP and LHDNM should already fill most of the necessary information requested by PADU. Under KWSP, 15.7 million members, which consists of formal employers, employees, and self-employed individuals, contain details about the employment and income of these individuals.[16] On top of that, the information gathered by LHDNM in the Rahmah Cash Assistance Scheme (STR) programme covers 8.2 million individuals, including information about household members, employment status and self-reported income. These two databases, coupled with other existing information collected by various government departments, should be merged to form the basis of the PADU system.

With the government’s national record of all adult individuals in Malaysia, the first stage of data

consolidation minimises error from manual entry, prevents leakages from false reporting, and identifies those without or lack an official record via the national registration system. Subsequently, the second phase is to fill in the gap via alternative data-gathering mechanisms from incomplete data or individuals not captured in the existing system. The different demographics with incomplete official records warrant a different data-gathering approach.

The informal sector, representing 8.6% of the total workforce in 2021, is often overlooked in the

various government policies.[17] According to the Department of Statistics Malaysia, there were about 3.5 million informal workers in Malaysia, of whom 57% worked in the informal sector while another 43% were in the formal sector.[18] The data on informal workers may not be sufficiently captured in existing formal government databases. PADU-enabled digital updating of this information would be useful to fill this gap.

The role of local government in defining PADU’s success

Data reconciliation is crucial to ensure that the data is up-to-date and accurate. Information discrepancies should be reported and investigated further to avoid leakages and ensure that vulnerable groups are not left behind. Local government bodies such as village chiefs (MPKK) and state assembly persons (ADUN) play an important role in ensuring that every family and individual are taken care of and their particulars are constantly updated and included in the centralised database. They would also be the best channel to reach the underprivileged and vulnerable, who cannot update the system themselves via digital means. For instance, the local constituency leaders would act as a bridge in helping older people and people experiencing poverty to register and update their information on PADU. Furthermore, ADUN and MPKK, who work the ground, would best understand the demographics and needs of their constituencies.

Cross-department data-sharing to enhance the government’s function

Relevant data from the centralised system needs to be made available to various government agencies

based on department functions. Sharing the database across departments, including federal and state agencies, would go beyond aiding welfare development programmes and improving the efficiency of government administration. As a case in point, applications for government programmes such as housing and school assistance could do away with manual paper documentation and move into a seamless digital process with already verified information kept within the system. Beyond that, data sharing from the federal to the state echelons means that individuals do not need to submit stacks of documents for every new grant or subsidy scheme.

However, an open data system within government agencies would raise concerns about data privacy. Hence, we recommend that each department only be given access to data that directly concerns its job function. A data protocol should also be established to prevent data leakages and misuse. We also recommend that the government set up a data management committee to handle and review data breaches and provide authorisation to agencies requesting data access beyond what was given.

Upgrading and maintaining a state-of-the-art IT security system to enhance data protection

Data security is crucial for any public sector organisation, as they handle sensitive information about

citizens and critical infrastructure. Strong access controls and multi-factor authentication to restrict access to sensitive data have to be in place to enhance data protection and increase confidence among the public. This system must scan regularly for vulnerabilities and promptly patch eventual irregularities. Qualified professionals are necessary to regularly educate employees on cyber threats and best practices for safe data handling.

To strengthen the governance data framework, establishing a clear data governance framework outlining procedures for data access, management, and disposal is urgently needed to create a trustworthy database system. The government should also consider identifying and assessing potential data security risks and implement appropriate mitigation strategies. Most importantly, PADU has to be transparent about data security practices and communicate potential risks and breaches to stakeholders. Furthermore, this is an ongoing exercise where continuous monitoring, assessment, and adaptation are crucial to keeping pace with evolving threats and vulnerabilities.

PADU as enabler for a long-term welfare and social policy ecosystem

Better and more complete data enables the government to roll out social programmes that are more inclusive, efficient, and effective. We recommend that the government use the data gathered for evidence-based subsidy targeting mechanisms. Data-based welfare systems, such as identifying needy populations, who they are, and why they remain poor, would be useful in crafting a pathway out of poverty.

Very often, contextual elements play a big role. For instance, if the government finds most young males in a particular city or village unemployed and job insecure, the government can provide training schemes for this group in the local in-demand industries. On the other hand, more elderly poor in a particular region means that the social security system is not robust enough in the context of that region, whether because of the regional employment trends towards the informal sector, which does not enrol the workers in the public social security services like EPF and SOCSO, or that most of the workforce is unskilled and received low wages which now renders them vulnerable in old age. We recommend that the government adopt high-quality research using the data gathered by PADU to inform welfare policy.

We also recommend that the government take a long-term view of welfare and social development. While it is important that the poor receive essential assistance and cash assistance, which have been known to increase children’s education, higher household consumption of food items, and, to some extent, poverty reduction in the short run[19],[20],[21],[22] the reliance on government’s handout increases dependency and induces lower earnings amongst aid recipient compared to their peers who do not receive the handouts.[23] Hence, PADU can act as a data enabler to complement the government’s needs to assess the long-term implications of its policies.

Concluding Remarks: Potential for PADU to Provide Digital One-stop Access to Government Services

PADU is a system that opens up many opportunities to enhance digital governance. A comprehensive data system reduces information asymmetry in policymaking and enables nuanced and inclusive aid distribution and forward-thinking policies. Data security, misuse of data, and self-reporting are concerns with such a system, which needs to be patched via an enhanced IT infrastructure and consolidation with existing databases.

The potential of PADU traverses beyond a national databank for welfare and subsidies. The system has the potential to hasten our pathway towards digital governance that synthesises the two-way flow of information from the government to the people.[24] The future of digital one-stop access to government services enabled by the system, in the form of a citizen-accessible and personalised digital ID, would be transformational in enhancing public services, spanning from renewing a driving license, applying for public housing, obtaining EPF information, registering for government grants, queuing digitally for government appointments and services, and in healthcare in the form of health records, diagnosis report, and making digital appointments.

Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng

Editorial Team: Iylia De Silva and Nur Fitriah (Designer)

Footnotes

[1] New Straits Times (2024, January 22). Malaysians remain hesitant as Padu registration reaches 1.3 million. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2024/01/1004142/malaysians-remain-hesitant-padu-registration-reaches-13-million

[2] The Star (2024, January 22). Civil servants required to update data on Padu by Feb 15. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2024/01/22/civil-servants-required-to-update-data-on-padu-by-feb-15

[3] Bernama (2024, 2 February). Last-minute Padu sign-ups can cause system congestion, says chief statistician. The Edge. https://theedgemalaysia.com/node/699596

[4] Annuar (2024). Purge data and restart: Experts urge Malaysia govt to fix security flaws in new central database. The Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/purge-data-and-restart-experts-urge-malaysia-govt-to-fix-security-flaws-in-new-central-database

[5] Salim & Lim (2023). Rafizi: Govt to roll out targeted subsidy for RON95 petrol in 2H2024. The Edge Malaysia. https://theedgemalaysia.com/node/691492

[6] Bernama (2024). PADU: Concerns of M40 singles need to be examined – Experts. Astro Awani. https://www.astroawani.com/berita-malaysia/padu-concerns-m40-singles-need-be-examined-experts-452618?

[7] Tan, Ben (2023). Report: Malaysia’s data breach cases hit all-time high, with four-fold increase recorded in 2023. Malay Mail. https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2023/09/21/report-malaysias-data-breach-cases-hit-all-time-high-with-four-fold-increase-recorded-in-2023/92075

[8] Ibid.

[9] Yeoh, Angelin (2023). CyberSecurity Malaysia report: Government sectors suffered most data breaches, while telcos spilled over 400GB of data in H1 2023. The Star. https://www.thestar.com.my/tech/tech-news/2023/10/25/cybersecurity-malaysia-report-government-sectors-suffered-most-data-breaches-while-telcos-spilled-over-400gb-of-data-in-h1-2023

[10] Haqeem, Khairul (2023). Recurring Data Breaches in Malaysia – Plain Ignorance or Just Weak Enforcement. Cybersecurity ASEAN. https://cybersecurityasean.com/daily-news/recurring-data-breaches-malaysia-plain-ignorance-or-just-weak-enforcement

[11] Kröger, Jacob Leon and Miceli, Milagros and Müller, Florian, How Data Can Be Used Against People: A Classification of Personal Data Misuses (December 30, 2021). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3887097 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3887097

[12] Chief Chapree (2024). Critical password flaw found within hours of Padu database launch. Malay Mail. https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2024/01/03/critical-password-flaw-found-within-hours-of-padu-database-launch/110374#google_vignette

[13] Sekaran, R. (2024). Economy Ministry swiftly fixes security loophole in Padu, thanks user for highlighting issue. The Star. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2024/01/03/economy-ministry-swiftly-fixes-security-flaw-in-padu-thanks-user-for-highlighting-loophole

[14] Boo, Su-Lyn (2018). The Influence Industry Voter Data in Malaysia’s 2018 Elections.

[15] Asyraf, Faisal (2024). Govt won’t misuse Padu data at elections, says Fahmi. Free Malaysia Today. https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2024/01/06/govt-wont-misuse-padu-data-at-elections-says-fahmi/

[16] KWSP (2022). Corporate Profile. https://www.kwsp.gov.my/about-epf/corporate-profile

[17] DOSM (2021). Informal Sector and Informal Employment Survey Report, Malaysia 2021. https://v1.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.phpr=column/cthemeByCat&cat=158&bul_id=NUhQNy9Eb1YxYkxxMVhFU0tIb0dQdz09&menu_id=Tm8zcnRjdVRNWWlpWjRlbmtlaDk1UT09

[18] The Star (2022). About 3.5 million people ‘informally employed’ in Malaysia in 2021. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2022/12/30/about-35-million-people-039informally-employed039-in-malaysia-in-2021#:~:text=PUTRAJAYA%3A%20Malaysia’s%20informal%20employment%20has,the%20Statistics%20Department%20(DOSM).

[19] Skoufias, Emmanuel, Mishel Unar and Teresa Gonzalez de Cossio (2013). The poverty impacts of cash and in-kind transfers: experimental evidence from rural Mexico. Journal of Development Effectiveness. 5(4): 401-429. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2013.843578

[20] Meng, C. and Pfau, W.D. (2012). Simulating the Impacts of Cash Transfers on Poverty and School Attendance: The Case of Cambodia. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 33. pp. 436–452. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-012-9292-5

[21] Wu, Alfred M. and M. Ramesh (2014). Poverty Reduction in Urban China: The Impact of Cash Transfers. Social Policy and Society. 13(2): 285-299. doi: 10.1017/S1474746413000626

[22] Aizer, Anna, Shari Eli, Joseph Ferrie, and Adriana Lleras-Muney (2016). The Long-Run Impact of Cash Transfers to Poor Families. American Economic Review. 106(4). pp. 935-71. doi: 10.1257/aer.20140529

[23] Price, David J. and Jae Song (2018). The Long-Term Effects of Cash Assistance. IRS Working Papers. No. 621

[24] Ivanova, Marina, Tatiana Yakovleva and Tamara Selenteva (2020). The Models of Information Asymmetry in the Context of Digitization of Government. Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference – Digital Transformation on Manufacturing, Infrastructure and Service. November. No.: 32, pp 1–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/3446434.3446512

You might also like:

A Critical Time for Penang's Fragile Creative Ecosystem

Raising the Alarm: Urgent Reforms Needed to Address PISA and Propel STEM Education

Food and Nutrition Security for Urban Low-income Households in Penang

Covid-19 Fuels Democratic Decline in Southeast Asia

A Proposal for Carbon Price-and-Rebate (CPR) in Malaysia