EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Emergency measures adopted to combat the Covid-19 health crisis threatens to fuel democratic decline.

- In combating Covid-19, some governments in the region have found it necessary to repress media freedom, hold impartial elections, declare a state of emergency and even allow stronger military influence in governing the country. This dire situation, however necessary, leads to democratic decline, and can easily be exploited by insecure leaders for longer term political gain.

- As checks and balances in governance falter, and restrictions are put in place to curb freedom of expression and association, the protection of human rights is compromised.

- To safeguard democracy during the crisis, therefore, governments need to ensure that their emergency measures are as time-restricted as possible. They should also allow media freedom, safeguard marginalized communities and ensure that financial support and all forms of donation are securely channeled to the right recipients. Corruption in times of limited public oversight can easily grow rampant.

- More than ever, donors should ensure that a country’s commitment to democratic processes and human rights remain a basic criterion for receiving international aids, grants or loans.

Introduction

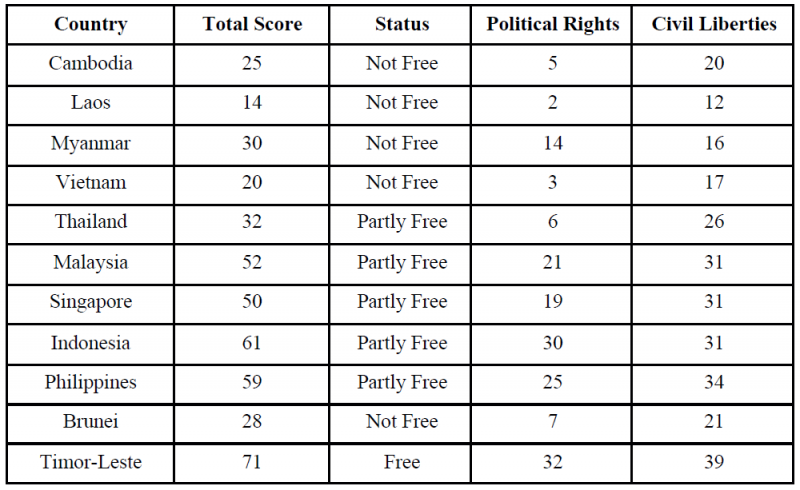

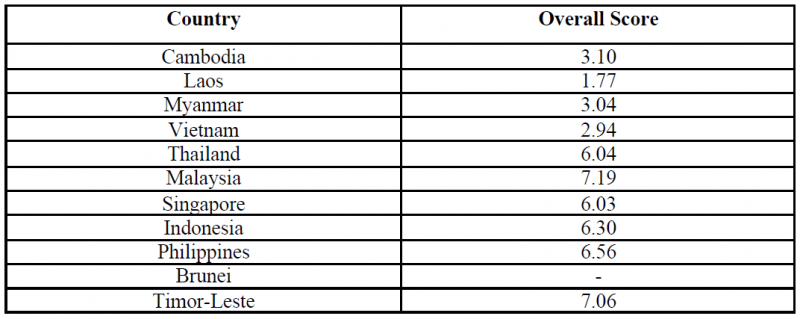

The Covid-19 pandemic has forced governments around the world to impose lockdowns, close borders and shut down certain economic sectors. These drastic measures, however necessary in the immediate term, has simultaneously fuelled democratic regression around the world. A study conducted by Freedom House (Repucci and Slipowitz, 2020) discovers this to have happened in 80 countries, and is particularly acute in repressive states and struggling democracies. Similarly, the Economic Intelligence Unit found that the global average score of democracy index hit an all-time low in 2020 (EIU 2021, p.4).

This paper takes a closer look at the state of democracy in a few Southeast Asian countries over the last twelve months. In particular, the paper focuses on Thailand, Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia and Myanmar. Following that, it is argued that this should not be taken lightly, and that democracy needs very much to be defended during these trying times. In conclusion, a few recommendations are proposed.

Freedom in Southeast Asia

Democracy Index

The Southeast Asian region has never been a bastion of democracy. While elections are held regularly, there are many laws that curtail impartial elections. And while there is freedom of expression and association, there are a series of off-limit subjects and draconian laws that compel self-censorship on the part of the citizenry. In general, incumbents are able to take advantage of existing institutions and social networks to prolong their hold on power.

Governments across the region acknowledge the importance of human rights, but not without grave incongruences between word and action. Countries such as Indonesia, Philippines and Thailand have all in recent years experienced deterioration in political freedom and civil rights, and with the coming of Covid-19, democratic regression becomes a matter of course.

The following paragraphs will discuss how the coronavirus outbreak is being exploited by some of the region’s regimes to further their own political interests. Before that, a brief description on what democracy regression entails is provided.

Democracy Regression in a Pandemic

Features of democratic decline include a general lack of checks and balances in various institutions, increasing restrictions in freedom of speech and association, failure in the protection of human rights and an absence of impartial elections. A gradual progression towards a more authoritarian state is a clear way for observers to detect democratic decline. Instead of a straightforward coup d’etat, executive aggrandizement seems to have become a more common path to take for authoritarians.

Executive aggrandizement happens when the executive branch of the government curtails opposition by eroding the power of the legislature and the judicial branch. For example, political allies are rewarded while critics are punished, and independent news media and civil and political liberties are curtailed while constitutional checks on power and rule of law in general are degraded (Croissant 2019, Bermeo 2016 and Khaitan 2019).

Thailand

Executive aggrandizement in Thailand had been occurring for some time, with Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-o-Cha militarising the cabinet, parliament and state-owned enterprises years before the Covid-19 pandemic (Kongkrati and Kanchoochat 2018).

In the run-up to the 2019 elections, the Thai government even enforced a cyber-security law to monitor media expressions and curtail information that were deemed unfavourable to the incumbent. The Future Forward party came from nowhere to win 18 % of the popular vote and 81 of the total 500 seats. Shocked by this, the government led by the Palang Pracharath party found pretext to dissolve that party, and banned its leaders, Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit and Piyabutr Saengkanokkul from holding political office (Butler 2020). Outraged supporters of Future Forward party soon organised protests in the form of “flash mobs”, and these were followed by more organiaed rallies which have lasted for months.

As voices of opposition grow, the prime minister has extended an existing state of emergency, which was originally meant to control the spread of Covid-19, to include a ban on assemblies of more than five people. It also allows authorities to detain suspects for up to 30 days without charge. Since March 2020, the Thai government has extended the order of the state of emergency eight times. Some pro-democracy activists have also been detained and charged with sedition and other offences (Human Rights Watch 2020).

While the state of emergency allows the regime to act swiftly to curb the pandemic, it also raises questions as to what extent it is also meant to repress dissenting voices. Thailand’s illiberal trends are further exacerbated by Covid-19.

The Philippines

Amid the pandemic, The Philippines has been seeing further consolidation of executive power by President Eduardo Duterte. In announcing a Covid-19 lockdown, he also shut down national broadcaster Philippines ABS-CBN on 15 March 2020. The shutdown order was widely criticised as an attack on press freedom. Meanwhile, the CEO of Rappler (an online news website), Maria Ressa, was also charged multiple times for tax evasion and violation of laws that ban foreign ownership of the media. The pressure imposed on Rappler has been largely criticised by local and foreign media practitioners, and is also widely perceived as Duterte’s personal vendetta against the online news website.

An anti-terror law was also passed during the pandemic lockdown. This allows detention without a arrest warrant. With scrutiny and debate lacking, this gives enormous power to a small group of enforcers to decide who is a terrorist and who is not (Ressa 2020). Such a loose process is easily used to detain dissidents.

Perhaps, the most disturbing trend in The Philippines is the government’s decision to appoint retired military generals to head the public health crisis instead of public health experts. Clearly, The Philippines is taking a highly-militarised turn and the fourth estate is being severely repressed.

Malaysia

Malaysia earned applause for its initial success in fighting Covid-19. However, the Sabah state election held in September 2020 accelerated infections and the spread of the disease throughout the entire country. By January 2021, average cases per day averaged 3,500. At the same time, the fragile Perikatan Nasional government was further weakened when several Members of the Parliament from UMNO began to withdraw their support. Opposition parties have also questioned the legitimacy of the Prime Minister, often claiming that he had now definitely lost the people’s mandate, i.e. if he had ever had it.

Amid the volatile political climate and the runaway threat of Covid-19, Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin decided to declare a state of emergency on 12 January 2021. This state of emergency is scheduled to end in August, but with the declared possibility that it could end earlier or be extended. The decision to impose the state of emergency was largely criticised by the opposition parties and various civil society movements, with special reference to the various forms of movement control orders that had already been tested and made familiar to the public throughout 2020.

No parliamentary sitting is allowed, ordinances can be introduced without debate, and the army is allowed more authority. Considering the mounting pressure facing the incumbent, the declaration of emergency has been widely interpreted by observers as the incumbent’s attempt to avoid a snap election and to buy him time to consolidate power.

Indonesia

The Covid-19 pandemic has hit Indonesia far worse than its neighbours. Although the Sinovac vaccine has already been rolled out, it will take some time before the region’s most populous nation manage to inoculate a majority of its population. Notwithstanding President Joko Widodo’s failures in handling the pandemic, Indonesians are generally satisfied with his administration.

There is however a sharp decline in Indonesians’ satisfaction with democracy (Pepinsky 2021). In recent times, there have been apparent attempts by the authorities to utilise legal means to stop criticism of the incumbent and to suppress alternative views. These measures are usually packaged as defence of Indonesian pluralism (Pepinsky 2021). Covid-19 has thus enhanced illiberal trends in Indonesia, and the Indonesian army has been tasked with non-security responsibilities.

The Indonesia military and police officers are infamous for arbitrary detention and discrimination against the LGBT community, hardline Islamist groups and even student protesters. Human rights protection for all segments of the Indonesia society remain low. With restrictions on freedom of speech put into place under the pretext of ensuring political stability, and with the gradually growing dependence on the army, Indonesia is also showing signs of democratic decline.

Myanmar

Despite the enormous challenges posed by the pandemic, Myanmar held its general election in November 2020. The National League of Democracy party led by state counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi secured a landslide victory. Under pandemic conditions, it was unlikely that the election would be impartial. There were clear political inclinations towards impartiality as well. In the run up to the election, the Union Election Commission (UEC) required all political parties to submit campaign broadcasts on state-owned media before the broadcast. This effectively empowered the UEC to censor campaign messages that were unfavourable to the military. The government also disallowed voting in minority areas such as the Rakhine, Shan, Kachin and Kayin states.

Activists who called for a boycott in the months prior to the election were threatened with legal action by the UEC (Article19, 2020). The manipulation of electoral laws suggests that the incumbent was committed to strengthening the mandate of the NLD instead of holding a truly competitive election. In Myanmar, the health crisis has been exploited to accelerate authoritarian trends. Minorities were also denied an opportunity for direct political participation.

On 1 February 2021, the military seized power in a coup d’etat, and arrested Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and her associates, shut internet services and took news channels off the air. The military justified the coup by stating that there was widespread voter fraud during the November 2020 election. The unpopular coup may have put the last nail on the coffin of the fragile democracy in Myanmar.

Danger of Democratic Decline

Democracy in Southeast Asia has seen ebb and flow, recent development suggests that democracy in the region is further beset by the pandemic and insecure power holders.

In countries such as The Philippines, Thailand, Myanmar and Indonesia, higher military intervention in civilian affairs have been enhanced. It must be noted that any amalgamation of civil-military authority usually has a higher tendency to take on a more hawkish tone. The coup in Myanmar is an example of the danger of such relations.

Media freedom has also been severely restricted especially in The Philippines and Myanmar. While the government may think that this could censor criticisms or stifle debates, it also means that citizens are denied timely and accurate information on the pandemic. Without accurate information, the people will not be able to arm themselves better to combat Covid-19, which could further derail state-led responses to combat Covid-19.

In Malaysia, power is concentrated in the hands of a selected few. As the country struggles to contain the third phase of Covid-19, there is an absence of healthy bipartisan debate, which mutes alternative suggestions to contain the pandemic. The emergency declaration, even if it is on the pretext of combating the pandemic, is a dangerous precedence in disaster control.

What is most worrying in the region is that special laws introduced during the pandemic will be difficult to reverse. When checks and balances are weakened, the rights of minorities, especially, will be relegated to the periphery and be unprotected, corruption at the top will increase, and freedom of speech will be severely restricted. Dissidents of the state will also face higher risks of suppression. In other words, a semblance of democracy will be retained but it will be increasingly void of substance. Left unchallenged, undemocratic norms can be normalised beyond the pandemic.

When democracy is in decline, it may be the common folk who will suffer and be denied access to accurate information, trustworthy institutions and freedom of expression; but in the long run, the state will also suffer as it will bereft of healthy debates.

The region faces difficult times ahead, and ensuring transparency and accountability in governance should remain a top priority for all concerned. Specifically, governments, civil society organisations, media practitioners and international donors can help safeguard democracy by keeping the following in mind:

1. Time-restrict emergency measures

Emergency measures such as restrictions in movements is one of the most prevalent options chosen by governments in the region to combat the pandemic. But even when they appear necessary, they must be time-restricted, and more vitally, governments need to communicate clearly to convince the public that these measures are indeed short term. The implementation of such measures must be proportionate to the threat, and at the same time, be tactical and adaptive to specific conditions.

2. Maintain a free and independent media

Accurate information is especially critical in an pandemic, more so when a state of emergency is in place. Traditional media practitioners’ role as the fourth estate becomes all the more important in ensuring that the authorities do not abuse their power during this time. On their part, governments should not restrict media practitioners from doing their job, but assist them instead by providing up-to-date and accurate information. Meanwhile, media literacy should be inculcated among the public to combat fake news. Technical and financial support should be given to journalists whenever possible. Needless to say, clampdowns on reputable media outlets should be avoided, even when these are critical of the government.

3. Protect Human Rights

Human rights violations tend to accompany democratic decline. During a pandemic, minorities such as migrant workers, LGBT community, ethnic minorities, victims of domestic violence and other marginalised communities are rendered more vulnerable. They are easily scapegoated as the cause of the health crisis, or suffer other forms of pressure and abuse. Coupled with societal discrimination against some of these marginalised communities, efforts need to be taken to ensure that they are protected during these trying times. Governments need to communicate clearly to the public to discourage discrimination against these communities. NGOs that are working closely with these communities also need support from the government to be effective. Governments, NGOs and the media practitioners all have a role to play in making sure that all forms of discrimination against vulnerable groups do not go unnoticed.

4. Combat Corruption

Throughout 2020, foreign donors, private companies and philanthropists have all increased various forms of donation and support for countries to combat Covid-19. To ensure efficiency in the distribution of these assets, it is vital that corruption not be allowed to damage these good intentions. Donors could consider assessing a country’s commitment to the democratic process and to protection of human rights as basic criteria to be eligible for aid. Anti-corruption agencies and other civil society organisations should also be empowered to monitor the foreign aid process.

Conclusion

Emergency measures introduced during the pandemic, however necessary they may appear, hold strong negative implications for the future of democracy in Southeast Asian countries. Governments and concerned citizens need to be aware that the more governments derail democratic norms, the faster democracy declines. This is an especially serious problem in countries with no or little democratic culture to start with.

However fragile democratic institutions and processes may be in the region, they need to be defended, and more so than ever in a protracted crisis.

For list of references, kindly download the document to view.

Editor: Ooi Kee Beng

Editorial Team: Sheryl Teoh, Alexander Fernandez, Tan Lii Inn and Nur Fitriah (Designer)

You might also like:

Unleashing Potential: Policy Insights for Malaysia’s Creative Industries

Combating Scam Syndicates in Malaysia and Southeast Asia

Cut the Queue: A Basket of Solutions for Malaysian Hospitals

Policy Uncertainty Remains a Major Consideration for Businesses in Penang and Malaysia

A Review of Malaysia’s Progressive Wage Policy White Paper