EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- On 30th November 2023, the Economic Minister tabled the Progressive Wage Policy (PWP) White Paper which in implementation is estimated to cost the Malaysian Government between RM2 billion to RM 5 billion a year.

- The goal is to push the country’s median wage to RM2,700/month by 2025 and, in the process, generate an 3.7% annual productivity growth rate from 2021 to 2025.

- The White Paper signals commendable political will to address the wage-productivity distortion effecting the labour and a positive direction towards the designing of targeted policies.

- It is however observed that the White Paper lacks a clearly defined problem statement, has not sufficiently draw on learnings from similar policies; specifically, the Productivity Linked Wage System (PLWS), and has not fully considered the possibility of how government-determined wage thresholds might lead to further distortions in the wage-productivity nexus.

- Three recommendations are presented, moving forward. First, to consider the hypothesis where firms are able, but unwilling to match wages to productivity. Second, to instead consider policy interventions which encourage fair bargaining of wages between employer and employees. Lastly, to consider the effect of the wage-productivity nexus in the public sector.

Introduction

On 30th November 2023, the Economic Minister tabled the Progressive Wage Policy (PWP) White Paper which is estimated to cost the Malaysian Government between RM2 billion to RM5 billion a year. The core idea for companies who pay employees at or above the government-determined wage to in recompense RM200/month (for entry-level positions) or RM300/month (for non-entry level positions) for 6 months, limited to a wage ceiling of RM5,000. The goal, citing the Twelfth Malaysian Plan (RMK-12), is to achieve a median wage of RM2,700/month by 2025 and generate an 3.7% annual productivity growth rate from 2021 to 2025.

Observations

Three observations are presented arising from the White Paper, taking into consideration the policy’s problem statement, design motivations and implementation.

1. The White Paper presents a holistic outlook of the labour market but stops short of a clearly defined problem statement

Chapter 1 of the White Paper presents a holistic outlook of the labour market with its associated datapoints. However, these datapoints stop short of proper synthesis to present a coherent argument for symptoms from the root causes. Without a clearly defined problem statement to conclude Chapter 1, one questions whether the problem is of quality of education, skills mismatch, wage suppression or a host of other plausible candidates.

Framing of the PWP however signals that the problem being addressed is a “wage problem”. More specifically, the assumption is that firms want, but cannot afford to pay workers or determine a wage commensurate to their employee’s productivity level; hence the need for the tiered incentive. Evidence for this is not presented.

2. The White Paper does well to build on previous related policies but offer no learnings from them; specifically, the Productivity Linked Wage System (PLWS)

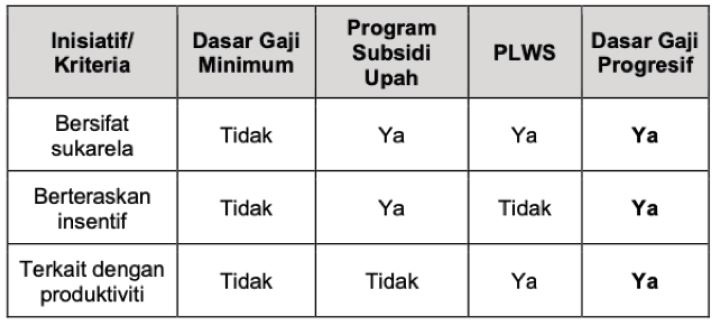

The Malaysian Government has promoted the Productivity Linked Wage System (PLWS) since 1996, and reports that as of November 2023, 97,799 firms have implemented the PLWS, benefiting 5.9 million employees.[1] Given that the only significant difference between the PLWS and PWP is that the latter is incentivised (see Figure 1), policy learnings from the long-implemented PLWS would certainly be instructive. This, however, is absent in the White Paper.

One might argue that if PLWS has been successful, why then has the distortion between the wage-productivity nexus not improved? And if so, what is the justification for the PWP – in this case, a RM5 billion subsidised version of the PLWS? Unless this is clarified, the PWP risks becoming a RM5 billion experiment, or worse, it may exacerbate the distortion by implicitly subsidising firm profits.

Figure 1: Comparison of wage-related initiatives by main criteria

Source: White Paper on Progressive Wage Policy Proposal

3. While a positive direction towards the designing of targeted policies, the proposed government-determined wage thresholds might further distort the wage-productivity nexus

Unless the Malaysian government can accurately determine productivity-linked wage thresholds down to individual firms and jobs, any threshold might further distort the wage-productivity nexus through the anchoring bias effect. In this situation, an employee or firm would argue for the government-determined threshold to be a legitimate wage expectation to their benefit; for an employee, it is a higher wage without justifying distinctive skills and for a firm, the paying of low wages despite higher recorded productivity.

Additionally, the anchoring bias will also affect GLCs and MNCs, despite them being ineligible for the PWP. This may take the form of informal bargaining within the firm or through price negotiations with suppliers. The collective effect then might see the labour market tend towards the government-determined threshold, rather than be a correction in the wage-productivity nexus.

Recommendations

In response to the presented observations, three proposals are put forth:

1. Consider the hypothesis of a wage problem where firms are able but unwilling to match wages to productivity

Two data points from the White Paper are informative in establishing this hypothesis:

a) Wages are not increasing despite increasing productivity – indicating a “wage” rather than “productivity” problem; and

b) Share of Compensation of Employees (CE) has been decreasing while Gross Operating Surplus (GOS) has been increasing – indicating that higher portion of profits are going to capital owners or firms

Following from this, one can identify the “why” for various types of firms. The more granular this relationship can be distilled, the more targeted and effective the policy solution can be. As raised in Section 2 above, data and lessons from previous wage policies, including the recent Covid-19 wage subsidy program will be instructive. This research should be spearheaded by MOHR through the Institute of Labour Market Information and Analysis (ILMIA) given that the primary source of data is within MOHR and its agencies.

2. Consider policy intervention to reduce power disparity between employer and employees to encourage fair bargaining of wages

Contrary to the government-determined wage threshold in the PWP, this proposal posits that wage setting is better left as a bargaining process between employer and employees similar to the PLWS. This is primarily due to the unique and situational nature of each business where the ones most informed are those within the business – both employers and employees.

The Government however should intervene to reduce the power disparity. In this, the proposed amendment to Act 262 to increase the number of unions and members is commended. The Government may also take cue from the US which requires public companies to disclose the pay ratio between their top executives and their employee median. Such a policy will reduce the information asymmetry between employer and employee, and therefore reduce the power disparity.

3. Consider the effects of the wage-productivity nexus in the public sector

The public sector here refers to government agencies and government-owned companies (including subsidiaries) whose wages are not determined by the Public Service Department (JPA).

It is often argued that such bodies should have a “competitive” pay scale to compete with the private sector for talent. The flip side, however, is that many of these bodies are not beholden to profitability measures the way the private sector is. Rather, these bodies have a delegated policy or a socioeconomic mandate and with the government as the lender-of-last-resort; this is true even for bodies which are established with profit motives.

How then is productivity measured, and by association, the wage-productivity nexus established with these bodies? And to what extent or magnitude do these bodies contribute to the distortion in national statistics? While there are no publicly available information of how many such bodies exists, the Audit (Accounts of Companies) Order 2017 lists 1,858 firms owned by the government, while another estimates that in 2013, the government controlled an estimated 42% of market capitalisation via majority ownership of 35 companies and an estimated 6,342 companies ten levels down.[2]

Conclusion

The White Paper brings to light the critical issue of wage-productivity distortion affecting Malaysia’s labour market and demonstrates the government’s direction towards the design of targeted policies. This is commendable. However, key questions around the motivations and evidence thereof for the PWP is not well presented in the White Paper. This brings into question whether the PWP RM5 billion price-tag is justified. This is in contrast to cheaper alternatives like reducing the power disparity to encourage fair bargaining of wages between employers and employees as recommended in this paper.

For list of references, kindly download the document to view.

Editor: Ooi Kee Beng

Editorial Team: Alexander Fernandez and Nur Fitriah (Designer)

[1] https://jpp.mohr.gov.my/pengenalan

[2] Gomez et. al., (2018) Minister of Finance Incorporated: Ownership and Control of Corporate Malaysia

You might also like:

![Imagine an Education Hub: Leveraging Penang’s International School Ecosystem]()

Imagine an Education Hub: Leveraging Penang’s International School Ecosystem

![Crafting Employment for Persons with Learning Disabilities is a Sound Socio-economic Stratagem]()

Crafting Employment for Persons with Learning Disabilities is a Sound Socio-economic Stratagem

![Logging in Ulu Muda Forest Reserve: Is Penang’s Water Security under Threat?]()

Logging in Ulu Muda Forest Reserve: Is Penang’s Water Security under Threat?

![Lessons from Southeast Asia's Responses to Covid-19]()

Lessons from Southeast Asia's Responses to Covid-19

![Key Issues to Consider in Heritage Preservation]()

Key Issues to Consider in Heritage Preservation