Executive Summary

- In June 2017, the US President Donald Trump made the decision to withdraw from the Paris climate agreement – an action that was met with heavy criticism worldwide, as being misguided, and lacking in insight and vision

- Even if the US had continued to honour its commitment to the Paris climate agreement, it is still pertinent to assess the level of Penang’s vulnerability and resilience to the impact of climate change. Scientists have cautioned that the world passed the carbon threshold already in 2016 – breaking the 400 parts per million carbon dioxide record

- Penang is obliged to keep pace with Malaysia’s proposed adaptation as stated in Malaysia’s Second National Communication (NC2) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC); and to carry out, along with all other state governments, its own vulnerability assessments and to integrate elements of climate change adaptation into urbanisation and land use planning. This is to be done in collaboration with the Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-based Industry (MOA), Ministry of Urban Wellbeing, Housing and Local Government (MUWHLG) and Town and Country Planning Department (JPBD)

- The state governments are also responsible for managing coastal and water resources with the assistance of the Department of Irrigation and Drainage (DID) and the National Hydraulic Research Institute of Malaysia (NAHRIM).[1]

- The success of these national policies will depend upon the willingness of all stakeholders to pool their expert knowledge, technology and human resources towards developing a well-thought adaptation strategy

Introduction

The US President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris climate agreement has been met with heavy criticism domestically and internationally.

In Putrajaya, Natural Resources and Environment Minister Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar expressed deep concern and “profound regret” over this development. “Having ratified the Paris agreement which itself embodies the spirit of continuous progression and no backtracking, the action by US calls into question the sincerity and good faith on which all multilateral agreements are negotiated and agreed,” he was quoted as saying in The Malaysian Insight.[2]

Trump’s decision, however, was not one that was made overnight.

Even before the President was sworn into office in January this year, he had, on many occasions during his campaign, declared that the climate change discourse was to blame for the US’ weakening economy – a phenomenon, in his words, built upon “alternative facts”. While his take on climate change was widely regarded as just one of his many uninformed opinions (his assumption that coal is still a valuable commodity in the global trade is one), the jokes and satire halted abruptly when Trump finally pulled the plug on the Paris climate agreement on June 1, 2017. Much to the chagrin of millions in the US and around the world, the move had a major ripple effect in the global climate change campaign – something that only an Annex 1 country with extremely high carbon emission like the US can manage.

The poor in developing countries stand out as one of the biggest losers in the US’ rollback, due to the shrinking Green Climate Fund. As part of the Paris climate agreement, this fund was set up to assist developing countries most vulnerable to climate change impacts. Via contributions to the Green Climate Fund, Annex 1 countries are to help developing countries improve their climate policy and their adaptation to natural disasters such as sea level rise and extreme weather events. If disregarded, these events would lead to myriad problems such as human displacement due to coastal flood, as well as food and water shortages.

The impact of Trump’s decision on climate change will not be felt immediately. As Martin Khor, the Executive Director of the South Centre, has said: “The United States will still be a member of the Paris agreement for the rest of Trump’s present term, although he announced he will not implement what Barack Obama had committed to, which is to cut emissions by 26%-28% from 2005 levels, by 2025. This defiance will likely have a depressing impact on other countries.” [3]

So what is it we should worry most about in this new situation?

If anything, this should give us fair warning that any climate agreement is not cast in stone. It is subject to (and under the mercy of) the powers that be. The US’ withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement dealt a heavy blow because prior to this, it had been one of the strongest champions in combating climate change. In the wake of this, our focus needs to shift to the new unsung heroes – the innovators and change makers around the world who have been tirelessly doing their part to reduce their carbon footprint – and will continue to do so despite the US’ withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement.

An elephant in the room that we need to address (and acknowledge) is China. Now that the US is no longer going to lead the fight against climate change, China is next in line to take over – but leadership is more than just signing agreements and committing to emission levels. Essentially, China should emerge as an unrivalled leader in green energy and technology – some even anticipate that it will achieve its Paris target early, alongside India. Currently, China is the world’s leading carbon polluter, and India ranks third on the list of countries with highest carbon emissions, with the US as number two. Together, their reductions are enough to outweigh the effect of Trump’s rollback of the US’ climate policy.[4]

In retrospect, what does the US’ withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement, and the consequent unbridling of its carbon emissions mean for Penang? What are the direct implications, if any? While it is too soon to say with certainty what the global impacts will be, Non-Annex 1 countries like Malaysia will now have to consider strengthening diplomatic ties with China, in order to secure a bilateral transfer of investments and technology.[5] In this scenario, Penang is poised to benefit economically if it presents itself as a potential and promising partner in the regional green economy and clean energy industries.

Local Level Acceptance of the Agreement

Besides improving its visibility as a strong player in the movement against climate change, Penang has a chance to join hands publicly with the rest of the world in adopting the Paris climate agreement at the local level and pushing for stronger climate action in the country.

In 2016, Malaysia signed the Paris climate agreement and pledged a 45% reduction of greenhouse emissions by 2030, and to cut as much as 32 million tonnes of carbon emissions by 2020. Malaysia is the fourth largest emitter of greenhouse gases in ASEAN, contributing 0.52% of the world’s carbon emission as of 2011.[6] However, from 2005 to 2015, it has managed to reduce 33% of its carbon dioxide emissions, an achievement which prompted the Prime Minister to increase the 40% carbon emissions reduction pledge to 45% in 2016.[7] In the report card of carbon emission reduction, one may surmise that Malaysia is doing quite well.

Even if the US had continued to honour its commitment in the Paris climate agreement, it is pertinent to assess the level of Penang’s vulnerability and resilience in the face of climate change impacts. Scientists have cautioned that the world has passed the carbon threshold – breaking the 400 parts per million carbon dioxide record in 2016.[8] This means that we have essentially drawn closer to the 1.5°C warming threshold, a key metric in the Paris climate agreement. The soaring levels of global warming will create serious repercussions such as extreme heat waves, droughts, coastal flooding and ocean acidification. Rightfully, the focus of climate change discussions should now move beyond mitigation (i.e. greenhouse gas reduction) and head towards adaptation and building resilience against climate change impacts.

In the grand scheme of things, is Penang standing on stable ground? What are the sea-level rise projections in the coastal areas of Penang? Do we know the extent of potential loss and damages incurred in the event of extreme stormwater surges? Have we established systems to deploy early warning and response measures in the event of flood and storm surges?

Contingency plans are equally important. Does Penang have enough shelters and the resources to minimise the loss of lives in extreme weather events? When disaster strikes, be it in the form of prolonged droughts, water shortages or scorching heatwaves, do we have enough food supplies and medical facilities to cater to the population? How is Penang preparing itself to increase its resilience against climate change impacts? These are some of the many questions that the state government needs to take immediate note of.

Penang is Not Sheltered

Penang is a member of the Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC) – a global network that connects governments, civil society and the private sector in committing to improve air quality and reduce short-lived climate pollutants. Headed by YB Phee Boon Poh (State Exco for Welfare, Caring Society and Environment), the team is coordinating disaster management planning efforts in Penang in the event of flood or storm surges.

A real-life example illustrating how vulnerable our coastal zones are to water surges is the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami generated by a 9.3 magnitude earthquake off Aceh. To this day, it is remembered worldwide as one of the most widespread and tragic natural disasters of its time. And like many natural disasters, it came unexpectedly, on a quiet morning the day after Christmas. No one could have prepared for a disaster of that scale. In a matter of hours, the tsunami ravaged the coastlines of 11 countries; taking with it 227,898 lives and leaving a massive trail of destruction in its wake.

Penang was not spared that day. The tsunami inflicted considerable physical damage (e.g. destroying jetties, properties, vehicles, aquaculture farms, etc), took 52 lives and displaced hundreds of citizens living along the coastline from George Town to Batu Ferringhi (including Pulau Betong). While the destruction and loss of lives in Penang was much less than that of other countries, the tragedy is still a wake-up call that our state is not as sheltered and free of natural disasters as once thought to be.

It has been 13 years since that fateful day and there has not been a natural disaster of that scale since. Yet we cannot afford to be complacent. Day by day, the impacts of climate change continue to gain momentum. It is only a matter of time before tangible impacts, such as storm surges and sea-level rises, materialise. Aside from coastal zone vulnerabilities, other climate change impacts such as prolonged periods of draught and rainfall can potentially wreak havoc on our food production, transportation and mobility, as well as various economic activities.

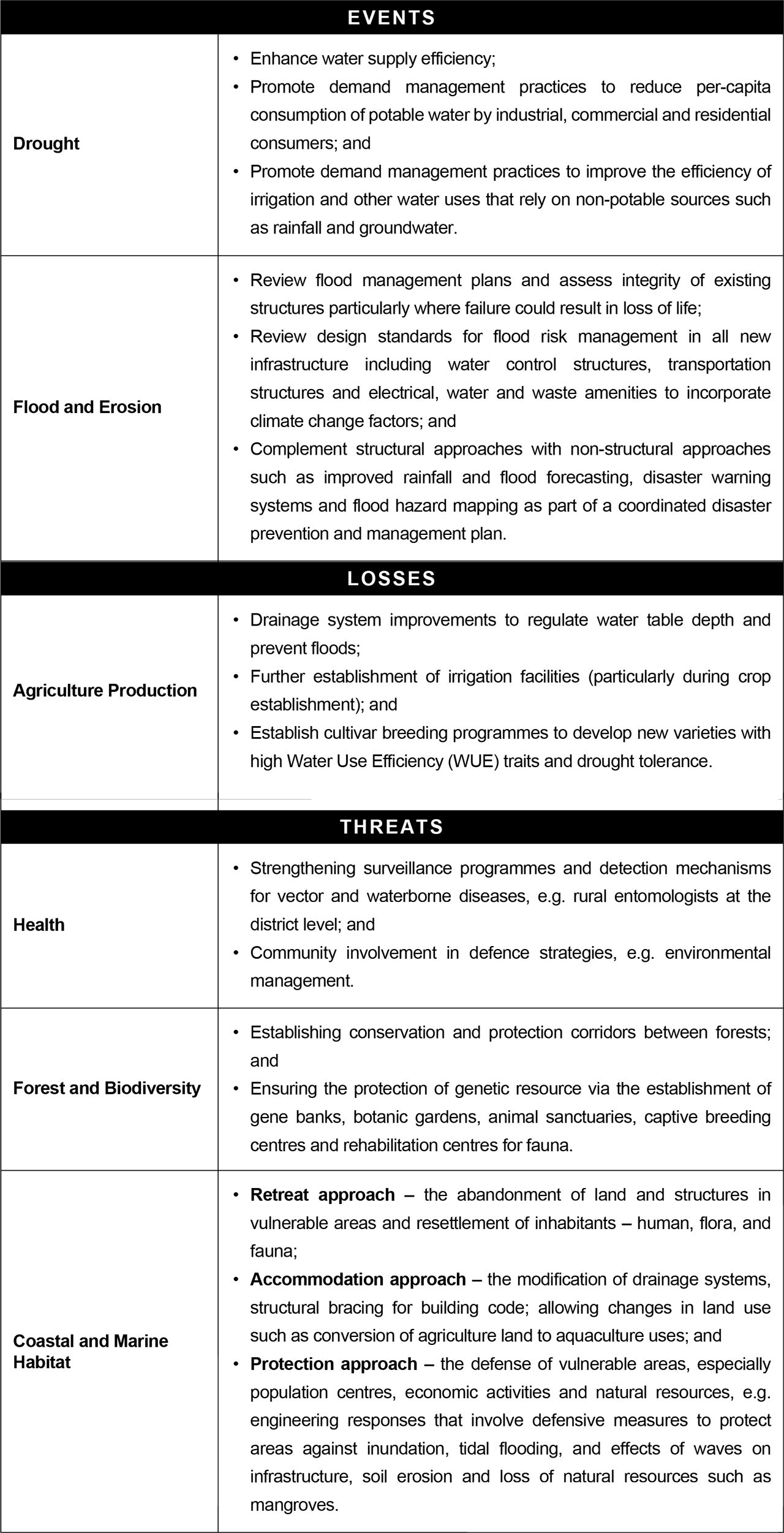

Penang is obliged to keep pace with Malaysia’s proposed adaptation as stated in the Malaysia’s Second National Communication (NC2) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (Table 1). Following a checklist of measures (see next page) is one way of assessing the state’s resiliency levels in the face of climate change impacts.

Each state government is responsible for carrying out its own vulnerability assessments and integrating elements of climate change adaptation into urbanisation and land use planning, in collaboration with the Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-based Industry (MOA), Ministry of Urban Wellbeing, Housing and Local Government (MUWHLG) and Town and Country Planning Department (JPBD). The state governments are also responsible for managing coastal and water resources with the assistance of the Department of Irrigation and Drainage (DID) and the National Hydraulic Research Institute of Malaysia (NAHRIM).[9]

As a starting point, the Penang Green Council (PGC), in partnership with Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM) and Water Watch Penang (WWP), conducted a state-wide survey in 2016 on public perception and awareness of climate change. The results of the survey were meant to aid policy makers in developing strategies to gear Penang towards becoming a greener state. It is therefore apt that the PGC has also been tasked to develop a “Penang Green Agenda” by incorporating Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to make Penang an environmentally sustainable state by 2030. Besides incorporating the SDGs, climate change adaptation measures stipulated in Malaysia’s NC2 should also be included.

Essentially, the context of “sustainability” is about future-proofing; implementing measures to ensure that our built environment and its systems will have the capacity to absorb shocks and continue to function despite rapidly evolving external forces. Regardless of who withdraws next from the Paris climate agreement, each of its members has an obligation to commit to increasing resiliency against the impacts of climate change. However, the success of national policies will depend upon the willingness of all stakeholders to pool their expert knowledge, technology and human resources towards developing a well-thought adaptation strategy.

Table 1: Malaysia’s Second National Communication (NC2) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)

[1] NRE (2008) Report on National Capacity Needs Self-Assessment for Global Environmental Management and National Capacity Action Plan. Government of Malaysia, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, Malaysia. 87pp.

[2] The Malaysian Insight. 2017. Putrajaya regrets US exit from Paris accord, calls it a setback. (2 June 2017) Accessed on 20 June 2017 <https://www.themalaysianinsight.com/s/4203/>

[3] The Star. 2017. Continuing the climate battle, without the US. Martin Khor. (June 5, 2017) Accessed on June 5, 2017.<http://www.thestar.com.my/opinion/columnists/global-trends/2017/06/05/continuing-the-climate-battle-withoutthe- us-with-president-trump-pulling-out-from-the-paris-agreeme/>

[4] Inside Climate News. 2017. China, India to Reach Climate Goals Years Early, as U.S. Likely to Fall Far Short. (May 16, 2017). Accessed on June 5, 2017. <https://insideclimatenews.org/news/15052017/china-india-paris-climate-goals-emissions-coal-renewable-energy>

[5] Non-Annex I Parties are mostly developing countries. Certain groups of developing countries are recognized by the Convention as being especially vulnerable to the adverse impacts of climate change, including countries with low-lying coastal areas and those prone to desertification and drought. Others (such as countries that rely heavily on income from fossil fuel production and commerce) feel more vulnerable to the potential economic impacts of climate change response measures. The Convention emphasizes activities that promise to answer the special needs and concerns of these vulnerable countries, such as investment, insurance and technology transfer.

[6] UNFCCC. Intended Nationally Determined Contribution of the Government of Malaysia. http://www4.unfccc.int/Submissions/INDC/Published%20Documents/Malaysia/1/INDC%20Malaysia%20Final%2027 %20November%202015%20Revised%20Final%20UNFCCC.pdf

[7] The Sun Daily. 2016. Malaysia’s carbon emission reduction rate on point, says expert. (21 April 2016) Accessed on 19 June 2017. <http://www.thesundaily.my/news/1774378

[8] Jones, N. 2017. How the World Passed a Carbon Threshold and Why It Matters. (January 26, 2017) Accessed on June 5, 2017. <http://e360.yale.edu/features/how-the-world-passed-a-carbon-threshold-400ppm-and-why-it-matters>

[9] NRE (2008) Report on National Capacity Needs Self-Assessment for Global Environmental Management and National Capacity Action Plan. Government of Malaysia, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, Malaysia. 87pp.

Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng Editorial Team: Regina Hoo, Lim Su Lin, Nur Fitriah, Ong Wooi Leng

You might also like:

![Food and Nutrition Security for Urban Low-income Households in Penang]()

Food and Nutrition Security for Urban Low-income Households in Penang

![Penang’s Economy to Remain Robust Despite Global Uncertainties]()

Penang’s Economy to Remain Robust Despite Global Uncertainties

![Protecting Women: An Overview of Women’s Legal Rights in Southeast Asia]()

Protecting Women: An Overview of Women’s Legal Rights in Southeast Asia

![Picking the Brains of GLC Heads: Policy Priorities for Penang in the Coming Decade]()

Picking the Brains of GLC Heads: Policy Priorities for Penang in the Coming Decade

![A Sustainable Active Ageing Policy for Penang]()

A Sustainable Active Ageing Policy for Penang