EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Artificial intelligence (AI) has become central to Malaysia’s digital economy, shaping financial services, biometric identification, customer service, and public administration.Yet, the same technologies have also amplified online scams, enabling criminals to deploy deepfakes, voice cloning, and automated phishing at unprecedented scale.

- Malaysia has seen sharp year-on-year increases in scam cases and financial losses,underscoring how fast these threats are evolving. Malaysia’s key cyber and data laws were enacted in a pre-AI era, and none of them provides clear definitions of synthetic media,impose obligations on platforms, or regulate automated decision-making.

- This paper highlights the need for Malaysia to undertake timely legislative reform to keep pace with AI-driven scams. Drawing on comparative lessons from neighbouring countries and international frameworks, it outlines a legal roadmap for modernising existing laws,expanding data protection, establishing dedicated governance mechanisms, and strengthening institutional oversight.

- By embedding these reforms, Malaysia can evolve from a reactive enforcement model to a preventive, rights-based legal framework that protects citizens, restores public trust, and positions Malaysia as a regional leader in AI governance.

Introduction: AI-Driven Scams as a National Challenge

AI-driven scams are fraudulent schemes that exploit artificial intelligence to enhance impersonation,automate deception, and manipulate victims at scale. AI enables criminals to create convincing deepfake videos, replicate voices of family members or officials, and deploy chatbots that conduct personalised conversations with thousands of victims simultaneously. These technologies combine mass reach with psychological precision, making scams harder to detect and prosecute (Tech for Good Institute, 2024).

In the first half of 2025 alone, Malaysians lost over RM1.12 billion to online scams,according to a written reply by the Home Ministry to Parliament (The Star, 2025).This represents a sharp escalation from previous years and highlights the inadequacy of current enforcement mechanisms.

While public statistics highlight the scale of financial losses, the deeper challenge lies in the inadequacy of the legal framework to counteract the problem. Current laws are not designed to regulate synthetic media, algorithmic manipulation, or cross-border AI syndicates.

The absence of AI-specific provisions undermines enforcement, creates loopholes for criminals, and erodes public confidence in digitalisation strategies such as MyDigital and Malaysia Madani(Ministry of Digital Malaysia, 2025).

Gaps in Malaysia’s Legal and Institutional Framework

While Malaysia has several statutes governing cybercrime, communications, and data protection,these laws were drafted in a pre-AI era. As the scam landscape shows, fraudsters increasingly exploit synthetic media, voice cloning, and algorithmic manipulation in ways that fall outside existing provisions. The main shortcomings can be grouped into three categories: outdated legislation, institutional fragmentation, and emerging harms and loopholes, highlighting the gaps in addressing AI-driven scams.

(i) Outdated Legislation and Narrow Statutory Definitions

Computer Crimes Act 1997 (CCA)

The Computer Crimes Act 1997 (CCA) criminalises unauthorised access, modification, and misuse of computer material. However, most AI scams involve authorised use of systems; for instance, the creating of fake dashboards or the generating of synthetic voices, which fall outside its scope (Mayer Brown LLP, 2024).

Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 (CMA)

Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 (CMA) criminalises “obscene,indecent, false, menacing or offensive” content but does not impose proactive obligations on platforms or telcos. A deepfake circulated online is only actionable after harm occurs, and even then, legal interpretation is uncertain (Parliament of Malaysia, 2024).

Personal Data Protection Act 2010 (PDPA)

The Personal Data Protection Act 2010 (PDPA) applies only to the private sector, leaving public agencies free to use citizens’ data in AI systems without statutory safeguards (JPDP, n.d.). It also lacks algorithmic transparency, rights against automated decision-making, or mandatory anonymisation of training datasets, which are safeguards now common in global privacy regimes (EUR-Lex, 2024).

AI-Generated Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM)

Under the Penal Code (ss. 377CA–E, 377D, 292, etc.) and the Sexual Offences Against Children Act 2017 (SOACA), it is a serious crime to produce, possess, or distribute child sexual abuse material.

Section 3 of SOACA defines a ‘child’ as a person under the age of 18, which presumes the existence of a real child. As a result, hyper-realistic AI-generated images or videos fall outside the statutory definition, even though they fuel paedophilic tendencies, normalise abuse,and may escalate to real-world offences.

Unless the law is amended to explicitly include computer-generated child images, Malaysia risks normalising a loophole that allows AI-generated CSAM to circulate unchecked.

(ii) Institutional Fragmentation and Jurisdictional Limits

Regulatory authority is split between the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission(MCMC), the Department of Personal Data Protection (JPDP), the Royal Malaysia Police (PDRM),and CyberSecurity Malaysia. Without a central AI oversight body, enforcement is reactive and fragmented, and is often slowed by overlapping mandates (NACSA, 2024).

In July 2025, the Digital Ministry confirmed that NACSA is finalising the Cyber Security Strategy 2025–2030, which will ‘take into account emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI)and all related cybersecurity threats’. The draft also reportedly includes establishing an AI security oversight committee to evaluate technical and ethical compliance (Bernama, 2025). While these developments are encouraging, the strategy remains in preparation and does not yet resolve the underlying issue of overlapping mandates.

Most AI scams originate abroad, but Malaysian law lacks provisions for cross-border asset freezes or rapid takedowns. Victims face difficulty pursuing remedies across jurisdictions (Interpol, 2024).

(iii) Emerging Harms and Loopholes

Non-Consensual and Defamatory Deepfakes

The Penal Code does not criminalise the creation of synthetic pornography where AI technology is used to attach a woman’s face or likeness onto another body. Existing provisions on obscenity (s.292) and insulting modesty (s.509) are outdated and assume real images. As such, victims of non-consensual deepfakes may have no recourse under current criminal law.

Malaysia’s Defamation Act 1957 and Penal Code ss.499–500 penalise false statements that harm reputation. However, these statutes do not explicitly cover AI-generated synthetic media where a person appears to say or do something defamatory. While courts may interpret deepfakes as defamatory, legal uncertainty remains since the law presumes human authorship.

Moral Panic and AI-Generated Disinformation

AI-generated misinformation has the potential to create public panic, such as fake videos of riots, disease outbreaks, or financial collapses. The Penal Code (s.505) and CMA (s.233) criminalise false statements and public mischief, but they were not drafted with synthetic media in mind. Enforcement is difficult when AI content is anonymously produced or hosted abroad.

AI-Generated Fraudulent Documents

The Penal Code (ss.463–477A) criminalises forgery, including making or using false documents.However, these provisions were drafted for physical or digitally altered human-made documents.AI-generated forgeries such as synthetic medical certificates, degree transcripts, or identity documents, are created entirely by AI rather than altered from originals, raising uncertainty over whether they fall within the statutory definition of a “false document.”

This creates enforcement challenges where hyper-realistic AI-generated documents are used to commit fraud against employers, insurers, universities, or financial institutions. For example, forged medical certificates could be used to obtain sick leave, or AI-generated transcripts submitted for employment applications. Without clear statutory provisions, prosecutions may fail due to definitional ambiguity.

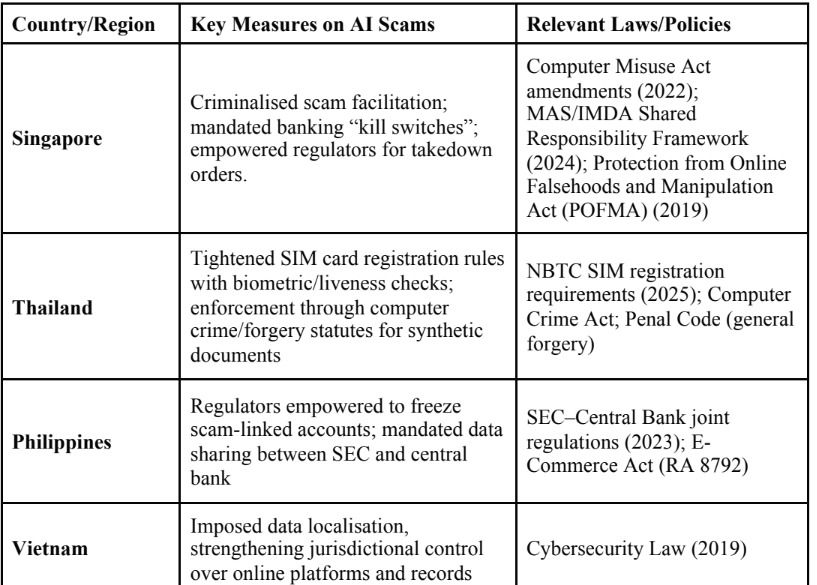

Regional and International Legal Comparisons

Malaysia is not alone in grappling with the legal challenges posed by AI-driven scams. Across ASEAN and further afield, governments have begun updating cybercrime, data protection, and platform regulation to address synthetic media, algorithmic fraud, and cross-border syndicates. Examining these approaches provides useful reference points for Malaysia, highlighting both regional peers and global leaders that have already acted to close the gaps identified in Malaysia’s Legal and Institutional Framework (Section 3 above).

(i)New Statutes and Cybercrime Updates

Singapore amended its Computer Misuse Act to criminalise facilitation of scams, mandated banking “kill switches,” and in December 2024 implemented a Shared Responsibility Framework (SRF) imposing shared liability for phishing scam losses across banks and telcos (Monetary Authority of Singapore, 2024; Channel News Asia, 2024).

In the United States, states such as California and Texas have enacted deepfake-specific statutes, including provisions criminalising election interference and impersonation (Justia, n.d.; Texas Legislature, 2019).

The European Union’s AI Act 2024, alongside the GDPR, provides rights against automated decision-making, mandates data minimisation, and classifies AI systems by risk level (EUR-Lex,2024).

(ii)Platform Duties and AI-Generated Disinformation

The United Kingdom’s Online Safety Act 2023 imposes statutory duties of care on platforms,requiring them to mitigate harmful and false content proactively (UK Government, 2024).Singapore’s Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA) empowers regulators to issue takedown or correction orders for online falsehoods, including those amplified by AI (Republic of Singapore, 2019).

Singapore’s POFMA and the UK’s Online Safety Act also illustrate rapid intervention powers against AI-generated misinformation that could trigger public panic (Republic of Singapore, 2019; UK Government, 2024).

(iii)Institutional Oversight and Cross-Border Regulation

The European Union has established national supervisory authorities to oversee AI compliance under

the AI Act, while the UK empowers Ofcom as the central regulator for online harms (Ofcom, 2025).

The Philippines has empowered regulators to freeze bank accounts linked to scams and mandated central bank–SEC data sharing (Tech for Good Institute, 2024). Vietnam’s Cybersecurity Law imposes data localisation, enabling stronger jurisdictional control (World Economic Forum, 2024).These measures highlight the importance of centralised oversight and stronger cross-border enforcement, both of which Malaysia currently lacks.

(iv) Addressing Specific Harms: Deepfakes, Fraudulent Documents, and CSAM

California’s Civil Code §1708.86 and the UK Online Safety Act 2023 explicitly criminalise non-consensual deepfake pornography and defamatory deepfakes, while the EU AI Act obliges platforms to detect and remove manipulated synthetic content (Justia, n.d.; UK Government, 2024).

Singapore’s Penal Code amendments clarify that electronic records qualify as “documents,” while the EU AI Act designates biometric ID and credential verification as high-risk applications requiring strict oversight (EUR-Lex, 2024).

The UK updated its Protection of Children Act 1978 and Criminal Justice Act 1988 to include “pseudo-photographs” of children, explicitly covering synthetic images. Australia criminalises AI-generated CSAM even where no real child is involved. By contrast, U.S. federal law remains limited after Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition (2002), though some states have closed the loophole.

Table 1 below summarises how selected jurisdictions have approached these categories of reform,

complementing the issue-based analysis above.

Figure 1:1 Table 1. Selected Jurisdictional Measures on AI-Driven Scams.

Policy Recommendations

1. Modernise Cybercrime Statutes

Malaysia should amend the Computer Crimes Act 1997 (CCA) to explicitly criminalise AI misuse including deepfakes, voice cloning, and algorithmic fraud. Current provisions fail to address impersonation scams where no “unauthorised access” occurs, leaving prosecutors to rely on weaker charges.

Similarly, the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 (CMA) must be amended to impose proactive duties on platforms: provenance tracking, content labelling, and rapid takedown mechanisms. The government is already moving in this direction with the forthcoming Online Safety Bill, scheduled for parliamentary debate in October–November 2025, which will mandate labels such as ‘AI-Generated’ or ‘AI-Enhanced’ and empower regulators with proactive takedown powers (Malay Mail, 2025; Bernama, 2025).

These changes would shift Malaysia from a reactive to a preventive model. Lessons can be drawn

from the UK’s Online Safety Act 2023 and Singapore’s Computer Misuse Act amendments, both of

which empower regulators to impose pre-emptive obligations on service providers (UK Government,

2024; AI Verify Foundation, 2024).

2. Expand Data Protection Law

The Personal Data Protection Act 2010 (PDPA) currently excludes the public sector, leaving significant gaps in oversight. To align with global practice, Malaysia should extend PDPA coverage to public bodies, introduce rights against automated decision-making, and mandate anonymisation of training data. Penalties should also be raised in line with international benchmarks such as the EU’s GDPR. The Department of Personal Data Protection (JPDP) should be empowered to conduct data protection audits on AI systems and require algorithmic impact assessments from deployers. These reforms would create whole-of-government accountability and rebuild public confidence (EUR-Lex,2024).

3. Enact an AI Governance Act

Malaysia requires a dedicated AI statute to harmonise scattered provisions. The Act should define “synthetic media,” “automated decision-making,” and “algorithmic bias,” establish a risk-based classification of AI systems, and empower regulators with audit powers. Criminal penalties should be introduced for malicious use of synthetic media, with aggravated offences where vulnerable victims are targeted. Drawing from the EU’s AI Act, this would ensure that Malaysia’s legislation is future-proof and interoperable with global frameworks (EUR-Lex, 2024).

In parallel, the Penal Code should be updated to define ‘synthetic documents’ and criminalise their creation or use for fraudulent purposes. Verification duties should extend to institutions most vulnerable to AI-generated forgeries, including universities, employers, insurers, and healthcare providers. Platforms that process applications or claims should be required to implement AI-detection

and verification mechanisms to identify synthetic documents.

4. Impose Platform Duties and Shared Liability

Banks and telcos must play a frontline role in scam prevention. Mandatory “kill switches” in banking apps, proactive blocking of scam SMS and calls, and shared liability regimes should be legislated. Singapore’s experience demonstrates that imposing liability on institutions creates strong incentives

for compliance. By contrast, Malaysia’s current model leaves responsibility with victims, eroding trust (Tech for Good Institute, 2024).

5. Establish an AI Regulatory Authority

Fragmentation across the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC), the

Department of Personal Data Protection (JPDP), the Royal Malaysia Police (PDRM), and the

National Cyber Security Agency (NACSA) creates delays and accountability gaps. Malaysia should

establish an independent AI Regulatory Authority with clear supervisory powers, including the ability

to impose fines and suspend non-compliant AI systems. The authority should coordinate across

financial, telecom, and enforcement agencies and represent Malaysia in ASEAN and global AI

governance forums. This centralisation would mirror the role of Ofcom in the UK’s Online Safety Act

and national supervisory authorities under the EU AI Act (Ofcom, 2025; EUR-Lex, 2024).

6. Regional and Global Leadership

Malaysia’s ASEAN chairmanship in 2025 provides a strategic opportunity. The country should propose an ASEAN protocol on AI-generated content, including common standards for transparency and regional rapid response to scam incidents. Bilateral cooperation with Singapore, Thailand, and Indonesia should be expanded to cover AI scams. Engagement with the EU and with ASEAN initiatives such as the ASEAN Guide on AI Governance and Ethics (2024) would further strengthen Malaysia’s role as a global voice in AI governance (Tech for Good Institute, 2024; ASEAN, 2024).

Conclusion

Malaysia’s current legal framework is inadequate for the AI era; it lacks provisions for synthetic media, algorithmic manipulation, and automated fraud. Institutional fragmentation and weak cross-border cooperation further limit enforcement.

By modernising cybercrime statutes, expanding data protection, enacting an AI Governance Act, imposing platform duties, creating an AI regulator, and driving ASEAN harmonisation, Malaysia can move from reactive enforcement to a preventive, rights-based framework. Such reforms would protect citizens, strengthen Malaysia’s digital economy, restore public trust, and position the country as a leader in responsible AI governance.

References

AI Verify Foundation. (2024). “Singapore’s approach to AI governance”. AI Verify Foundation.

https://www.aiverifyfoundation.sg/resources (accessed 11 August 2025)

ASEAN. (2024). ASEAN Guide on AI Governance and Ethics. ASEAN Secretariat.

https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/ASEAN-Guide-on-AI-Governance-and-Ethics_beauti

fied_201223_v2.pdf (accessed 24 September 2025)

Asiedu, E., Branstette, C., Gaekwad-Babulal, N., & Malokele, N. (2018). The effect of women’s representation in parliament and the passing of gender sensitive policies. In ASSA Annual Meeting (Philadelphia, 5-7 January). https://www. aeaweb. org/conference.

Azianura, H., Norazlin, K., & Norhuda, H. (2019). “Romance scams in Malaysia: A criminological

analysis”. GEMA Online Journal of Language Studies, 19(1):97-115. https://ukm.my/library/

romance-scams-malaysia.pdf (accessed 12 August 2025)/p>

Bernama. (2025, July 13). “Gov’t considering mandatory ‘AI-generated’ label under Online Safety

Act – Fahmi”. Bernama. https://www.bernama.com/en/news.php?id=2444805 (accessed 24 September 2025)

Bernama. (2025, July 30). “Malaysia finalising Cyber Security Strategy 2025–2030”. Bernama.

https://www.bernama.com/en/news.php?id=2451273 (accessed 24 September 2025)

Channel News Asia. (2024, October 25). “Banks, telcos to share responsibility for phishing scam

losses under new framework”. Channel News Asia. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/phishing-scams-banks-telcos-shared-responsibility-framework-dec-16-responsibilities-duties-4699236 (accessed 24 September 2025)

EUR-Lex. (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1689: The Artificial Intelligence Act. Official Journal of the European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32024R1689 (accessed 11 August 2025)

Interpol. (2024, June 27). “USD 257 million seized in global police crackdown against online scams(Operation First Light 2024)”. https://www.interpol.int/en/News-and-Events/News/2024/USD-257-

million-seized-in-global-police-crackdown-against-online-scams (accessed 24 September 2025)

JPDP. (n.d.). Personal Data Protection Act 2010: Frequently asked questions. Department of Personal Data Protection, Malaysia. https://www.pdp.gov.my/ppdpv1/en/faq/ (accessed 14 August 2025)

Justia. (n.d.). California Civil Code §1708.86. Justia US Law. https://law.justia.com/codes/california/civil-code/section-1708-86 (accessed 11 August 2025)

Malay Mail. (2025, July 29). “Govt mulling labels such as ‘AI-Generated’ or ‘AI-Enhanced’ to flag fake content online, says Fahmi”. Malay Mail. https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia /2025/07/29/ai-generated-govt-mulling-labels-to-flag-fake-content-online-says-fahmi/185650

(accessed 24 September 2025)

Mayer Brown LLP. (2024, May). “Artificial intelligence and the law in Asia”. Mayer Brown LLP.

https://www.mayerbrown.com/en/perspectives-events/publications/2024/05/artificial-intelligence-an

d-the-law-in-asia (accessed 13 August 2025)

Ministry of Digital Malaysia. (2021). Malaysia Digital Economy Blueprint (MyDIGITAL). https://www.mydigital.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/MyDIGITAL-Blueprint-Book.pdf

(accessed 14 August 2025)>

Mohd Akbal, A., Nur Adilah, M., & Siti Zaleha, A. (2024). “Investment scams and digital fraud in

Malaysia”. International Journal of Financial Crime Studies. https://ijfcstudies.org/article/ investment-scams-malaysia-2024 (accessed 15 August 2025)>

Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS). (2024, November 21). “MAS and IMDA announce implementation of Shared Responsibility Framework from 16 December 2024”. Monetary Authority of Singapore. https://www.mas.gov.sg/news/media-releases/2024/mas-and-imda-announce-implementation-of-shared-responsibility-framework-from-16-december-2024 (accessed 24 September 2025)>

NACSA. (2024). National Cyber Security Strategy Malaysia 2020–2024. National Cyber Security

Agency. https://www.nacsa.gov.my/strategy-2024 (accessed 11 August 2025)>

Nurul Faqihah, R., Ahmad Syukri, M., & Hafiz, A. (2024). “Macau scams and AI voice cloning in

Malaysia”. Journal of Criminology and Security Studies. https://jcass.org.my/

articles/macau-scams-ai-malaysia (accessed 16 August 2025)

Ofcom. (2025). “Online Safety Act: Roadmap and guidance for services”. Ofcom. https://www.

ofcom.org.uk/online-safety (accessed 12 August 2025)

Parliament of Malaysia. (2024). Hansard debate on Communications and Multimedia Act

amendments. Parliament of Malaysia. https://www.parlimen.gov.my/hansard-cma-amendments-2024

(accessed 14 August 2025)

Republic of Singapore. (2019). Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA).

Singapore Statutes Online. https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act/POFMA2019 (accessed 15 August 2025)

Tech for Good Institute. (2024). “Tackling scams in Southeast Asia’s digital economy”. Tech for

Good Institute. https://techforgoodinstitute.org/insights/tackling-scams-se-asia (accessed 11 August

2025)

Texas Legislature. (2019). Texas deepfake statute (SB 751). Texas Legislature Online.

https://capitol.texas.gov/billlookup/text.aspx?LegSess=86R&Bill=SB751 (accessed 13 August 2025)

The Star. (2025, August 14). “RM1.12bil in losses to online scam in first half of 2025, says Home

Ministry”. The Star. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2025/08/14/rm112bil-in-losses-to-on

line-scam-in-first-half-of-2025-says-home-ministry (accessed 24 September 2025)

UK Government. (2024). Online Safety Act 2023: Guidance and implementation. GOV.UK.

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/online-safety-act-2023 (accessed 16 August 2025)

UK Government. (2025, January 30). “Government introduces new offence criminalising deepfake

pornography”. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-offence-criminalising-deep

fake-pornography (accessed 24 September 2025)

World Economic Forum. (2024, March 19). “Vietnam’s cybersecurity law and data localisation”.

World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/03/vietnam-cybersecurity

-data-localisation (accessed 17 August 2025)

You might also like:

![Need for Speed: Survey Findings on Penang Internet Connectivity]()

Need for Speed: Survey Findings on Penang Internet Connectivity

![Covid-19 Fuels Democratic Decline in Southeast Asia]()

Covid-19 Fuels Democratic Decline in Southeast Asia

![Raising the Alarm: Urgent Reforms Needed to Address PISA and Propel STEM Education]()

Raising the Alarm: Urgent Reforms Needed to Address PISA and Propel STEM Education

![Helping SMEs Rise to Challenges Posed by the Covid-19 Pandemic]()

Helping SMEs Rise to Challenges Posed by the Covid-19 Pandemic

![Protecting Women: An Overview of Women’s Legal Rights in Southeast Asia]()

Protecting Women: An Overview of Women’s Legal Rights in Southeast Asia