Dr. Fauwaz Abdul Aziz (Project Researcher, History & Regional Studies Programme) and Muhammad Farhan Yaumil Ramadhan (Intern)

| Posted onEXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- After more than 50 years and 14 negotiations, ASEAN’s signing of the Treaty on Extradition (ATE) in November 2025 marks a significant collective response to the changing nature and impact of transnational crimes.

- The ATE does not create new supranational mechanisms or institutions, but it offers practicality over bilateral arrangements by providing a single, stable regional framework that simplifies extradition processes and strengthens cooperation among member-states’ law agencies.

- Given the ‘ASEAN Way’, the value of the ATE lies beyond legal provisions; it should foster the trust-building process, strengthen consensus, and deepen regional solidarity among member states.

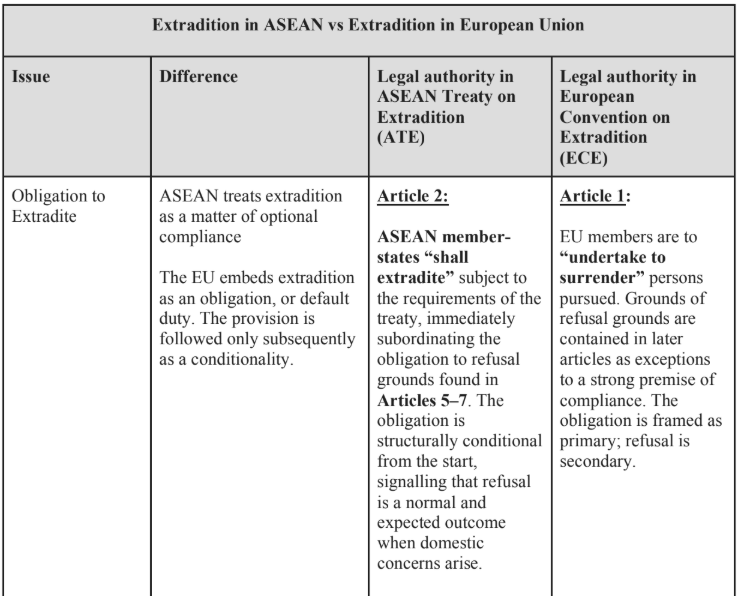

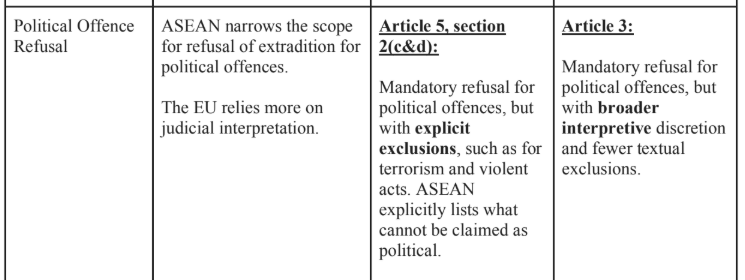

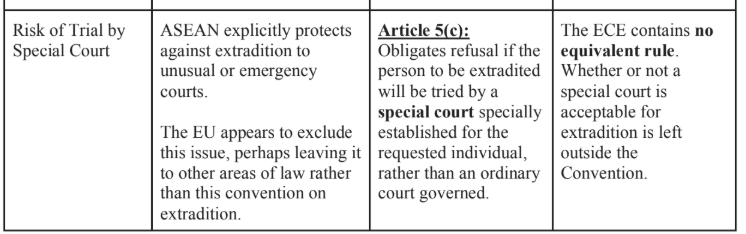

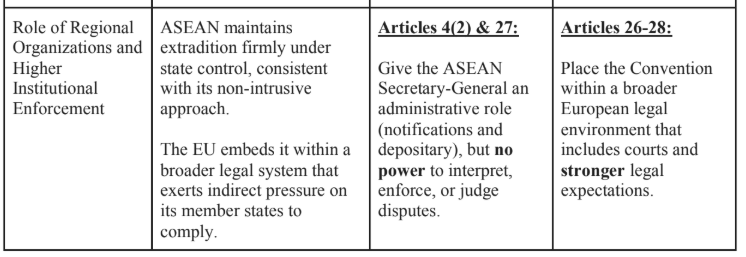

- In comparison with the European Convention of Extradition (ECE), the ASEAN ATE reflects the regional bloc’s distinctive legal approach, including compliance with domestic laws, administrative flexibility, and the region’s diversity.

- While implementation will face political and legal challenges, the ATE represents a meaningful step toward closing cooperation gaps and demonstrates that the process of cooperation itself is a strategic and commendable outcome.

Introduction

When businessman Jho Low, wanted by several governments for his role in the 1MDB scandal, was reportedly hiding in Myanmar[1], many questioned why the Malaysian government could not simply assert the country’s political will and request Naypyidaw to extradite the Penang-born fugitive. To many, Low’s presence just a two-hour flight from Malaysia suggested extradition would be a matter of only a few phone calls and exchanges of diplomatic letters and supporting documents between Putrajaya and Naypyidaw.

Many assumed Myanmar police could secure Low and return him to Malaysia to face charges first brought against him more than a decade ago. After all, it did not take long for Cambodia to accede to China’s extradition request of ‘scam kingpin’ Chen Zhi, which was brought to realisation a mere months after the request had been made.[2] Unfortunately, the issue is not merely about asserting political will. Beyond the fact that Malaysia is nothing like China where political clout is concerned, it does not have a bilateral extradition treaty with Myanmar; diplomatic cooperation is limited between the two; there is an absence of legal and judicial coordination; and the security situation in Myanmar is highly unstable.

Above all, extradition depends entirely on whether the Myanmar government chooses even to consider Malaysia’s request. Furthermore, if reports are to be believed, Low entered and exited Myanmar repeatedly over the past year, travelling widely using different passports, from Shanghai and Macau in China, to Cyprus in the eastern Mediterranean, and St Kitts and Nevis in the Caribbean.

In the larger scheme of things, money laundering is only one of many transnational crimes; governments worldwide have long been plagued by terrorism and trafficking in humans, wildlife, and drugs trafficking. Globally, cyber-scams alone have caused losses of between US$18 billion and US$37 billion in 2023, according to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime. Fugitives and individuals wanted to aide in the investigation of one crime or another, have exploited porous borders as well as legal-judicial systems and enforcement gaps to find safe haven in jurisdictions outside those they are wanted in.

Transnational crimes have reached unprecedented levels of scale and harm caused, and organizational capacity and sophistication – from smuggling and money laundering to financial fraud, online scams,and other cybercrimes. Politicians and policy-makers are facing increased pressure to demonstrate resolve, enhanced inter-governmental cooperation, and greater harmonisation among their enforcement agencies. Advancements in digital technologies have enabled many crimes committed in one jurisdiction to be detected only afterwards elsewhere by their victims and authorities.

While online scam victims are global, many criminal enterprises behind the cybercrimes are increasingly basing their operations in Southeast Asia. Undoubtedly, it was the increased spotlight on the regional governments’ commitment to the pursuit of justice and to prevent criminals from securing safe haven in their own territories that pressured ASEAN member-states to agree in late 2025 on a common platform to facilitate extradition requests between their legal and judicial institutions. On 14 November 2025, ASEAN’s 11 member states signed the ASEAN Treaty on Extradition (ATE) in Manila – this occurs 50 years and 14 negotiation rounds after the mandate for such an agreement was enshrined in the 1976 ASEAN Concord in Bali.

The Treaty

In one of the concluding weeks of the negotiations, a senior Philippine legal officer underscored the significance of the treaty: “The establishment of a comprehensive ASEAN Extradition Treaty is a crucial step in ensuring that criminals find no refuge, that impunity has no place in our region, and that justice transcends boundaries.”[3]

While bilateral extradition and mutual legal assistance agreements already exist between ASEAN member-states, a regional treaty on extradition offers greater stability and predictability: after all, regional treaties are less vulnerable to political change or non-compliance than bilateral arrangements. A regional agreement like the ATE ensures continuity in cross-border justice efforts; and while overlapping bilateral agreements complicate compliance, especially for developing states with limited legal resources, a single regional treaty simplifies procedures for officials involved in the making and receiving of extradition requests. The ATE numbers less than 27 pages.

‘The ASEAN Way’

Critics point out that the ATE has in effect not created any new institutions or enforcement mechanisms. Some question its value and effectiveness, given the absence of a supranational authority to ensure compliance, such as the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU).

Some experts argue that ASEAN should not be judged solely on the criterion whether there is or isn’t immediate, tangible, outcomes such as institutional mechanisms and bodies. They caution against applying Anglo-American or European historical experiences and expectations on ASEAN or any other region of the world.[4]

Important differences distinguish ASEAN from organizations such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) or the EU. Recognizing these differences enables stakeholders to engage more constructively with ASEAN governments to achieve their respective aspirations. In other words, ASEAN must be understood from the internal perspectives of its member states.

Among the differences between ASEAN and regional blocs elsewhere in the world are the greater stress on informality, consensus-building, managing conflict by working with cultural norms, values, and practices, and a sense of being serumpun, a Malay-language term connoting a sense of ‘family resemblances’, shared roots, and indigeneity.

These are in addition to the well-known ASEAN principles of respect for each member-state’s political, territorial and national integrity and the principle of non-interference; the peaceful management of disputes; mutual respect and cooperation; adherence to international laws; respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms; collective responsibility for peace, security, and prosperity; and emphasis on regional stability.[5]

The ATE is important both in terms of the advantages offered by the treaty itself, as well as the process that it entails and promotes. The ATE closes the cooperation gap between the national state agencies of ASEAN member-states, and strengthens rule of law and regional solidarity vis-à-vis the pursuit of justice and criminals. The means are the message.[6]

Despite its limitations and constraints, the ATE is important in terms of both the substance of the contents, as well as the cooperative process that it promotes and facilitates.

Policy Recommendation

To strengthen the ATE, ASEAN should prioritise improving the clarity of its legal provisions, strengthening safeguards in the amendments to domestic laws, and developing the impact of the treaty through practice rather than attempting to mimic the EU’s ECE supranational enforcement model.

While the 60-day provisional arrest period has raised some human rights concerns, it also reflects the unevenness of legal capacity and capability among ASEAN member states. Rather than shortening that period, ASEAN needs to push for a requirement for clearer procedural justification, notification, and periodic reviews to prevent its misuse and mismanagement while still preserving its flexibility.

On capital punishment risk, ASEAN should institutionalize written guarantees and peer consultation, so as not to override any member’s national laws, to reduce unintended outcomes, and to enhance confidence in extradition decisions.

Finally, greater transparency and accountability should be promoted and guaranteed through regular reporting on extradition requests and refusals, allowing states to learn from past practices.

These measures should not weaken sovereignty, but rather enhance mutual trust, which ASEAN already relies on as its primary principle for enforcement. In this sense, the ATE’s effectiveness will depend on whether ASEAN is willing to make this treaty implementable in a consistent and accountable manner.

The Way Ahead

ASEAN must now secure national approval and ratification by at least six member states for the treaty to take effect. This may mean that the next stage of the ATE will likely see protracted domestic political horse-trading and contestations, which may end up diluting certain treaty provisions.

Obstacles in the way include elite resistance (to the prospects of stricter control of transborder flows of capital and persons), differing legal systems (such as between Commonwealth and Continental legal and judicial systems, among others), and potential human rights concerns (such as freedom of expression and right to information). There are already many documented cases evidencing judicial and legal overreach by ASEAN governments.[7]

But if ASEAN is to maintain its relevance in contemporary crises and in facing transborder crimes, such challenges will need to be tackled head on. This will likely take longer than some people might wish, especially given ASEAN officials’ proclivity to carry out their business ‘the ASEAN way’, that is, involving what some quarters remark to be a lot of ‘sitting, eating, and nodding in meetings’.

References

1. Money and connections keep Jho Low safe, possibly in Shanghai, Macau or Myanmar. 2025, December 28. New Straits Times. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2025/12/1345689/money-and-connections-keep-jho-low-safe-possibly-shanghai-macau-or.

2. Grant Peck and Huizhong Wu. Cambodia extradites alleged scam kingpin Chen Zhi to China. 2025, January 8. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/cambodia-scam-chen-zhi-prince-group-china-b32da55af90841d6b2b95cc6334f3fa7

3. Philippine chief state counsel Dennis Arvin L. Chan, quoted in ‘Fugitives beware: ASEAN countries move closer to a unified extradition treaty’, March 5, 2025, ABOGADO.COM.PH. Available at https://abogado.com.ph/fugitives-beware-asean-coun-tries-move-closer-to-a-unified-extradition-treaty/

4. We thank Associate Professor of International Relations, Dr. Lily Yulyadi Arnakim of Binus University, Jakarta, for his convincing arguments on the matter. Interview conducted with Dr. Yulyadi online on December 18, 2025.

5. See the 1976 Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia, and the more recent ASEAN Charter, adopted in 2007.

6. As Dr. Yulyadi put it, “The process of seeking these goals is a goal in itself.” See, for example, Arnakim, L.Y., Karim, M. F., & Mursitama, T. N. (2021). Revisiting ASEAN Legislation and Its Impact on Regional Governance. Journal of ASEAN Studies, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.21512/jas.v9i2.8116

7. See, for example, the case of Murray Hunter, indicted in Thailand after Malaysia’s

You might also like:

![Penang’s Economy to Remain Robust Despite Global Uncertainties]()

Penang’s Economy to Remain Robust Despite Global Uncertainties

![Stuck in Traffic: Why Malaysia Does Not Have a Motorcycle Ride-hailing Sector]()

Stuck in Traffic: Why Malaysia Does Not Have a Motorcycle Ride-hailing Sector

![Synergy among Stakeholders is Key to the Sustainability of Cultural Tourism in Penang]()

Synergy among Stakeholders is Key to the Sustainability of Cultural Tourism in Penang

![Trend of Investments in Batu Kawan Industrial Park]()

Trend of Investments in Batu Kawan Industrial Park

![EU-Malaysia Trade Ties Strengthen despite Persistent Differences]()

EU-Malaysia Trade Ties Strengthen despite Persistent Differences