EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- This paper uses Impact Gaps Canvas to identify the various sustainability challenges facing Penang and how these will be addressed by the Penang Infrastructure Corporation’s (PIC) projects.

- PIC’s various infrastructural initiatives are examined based on principles of sustainable development. These undertakings are tantamount to sustainability strategies in Penang’s quest to strike the right balance between addressing human needs and pursuing ecosystem flourishing.

- Penang is facing many new challenges. For example. the southeast Asian region as a whole has become much more competitive. Rising industrialisation in neighbouring countries such as Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia is competing with Penang for E&E investment and jobs.

- Penangites naturally migrate when offered better opportunities. In fact, more than 47,000 out-migration occurred in Penang from 2012 to 2016, contributing further to the state’s long-term brain drain.

- PSR is the sustainability strategy undertaken by the Penang. Proximity to the airport leverages on the global logistical network. More than 80% of E&E products are exported from that airport, and electronic products are deliverable from Penang to the US within 28 hours. Furthermore, the existing E&E ecosystem is conducive for MNC and small-medium enterprises expansion.

Introduction

Launched in July 2020, the Penang Infrastructure Corporation Sdn. Bhd. (PIC) was the state government’s special-purpose-vehicle (SPV) tasked to implement a range of infrastructural projects such as Bayan Lepas Light Rail Transit (LRT), Pan Island Link (PIL), three major roads (Package 1, 2, 3), the third link between island and mainland, and the Penang South Reclamation (PSR) (Tan, 15 July 2020). The transportation-related projects are part of the Penang Transport Master Plan (PTMP).

PIC’s ambitious undertakings are sustainable developmental initiatives to transform Penang into a “family-focused green and smart state that inspires the nation,” upholding the Penang2030 vision of Chief Minister Chow Kon Yeow.

The backdrop for the anticipated transformation is a set of sustainability challenges facing Penang. This paper examines those challenges and identifies the existing gaps by using Impact Gaps Canvas analysis. The proposed solutions based on the PTMP and PSR will also be listed. As sustainable development is the underlying principle of these projects, it is important that we clarify the concept before we begin analysing the impact gaps.

Principles of Sustainable Development

Sustainable development is not environmental conservationist or exploitative. The point is neither to conserve nor plunder the given state of nature. Sadly, it is very common that we find conservationists misusing the concept to protest against sustainable initiatives as “greenwashing” and as cases of exploiters using the term to promote real estate projects.

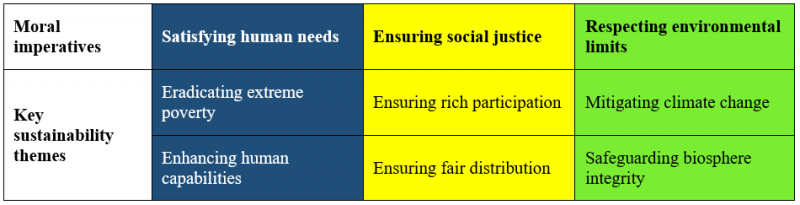

Sustainable development is first and foremost a perpetual quest to strike the right balance between addressing human needs (“anthropocentrism”) and pursuing ecosystem flourishing (“biocentrism”) (Keitsch, 2018). What constitute the right balance are the three E’s: economy, equity, and ecology. The authors of The Imperatives of Sustainable Development describe the E’s as the three moral imperatives of “satisfying human needs, ensuring social justice, and respecting environmental limits” (Holden et al, 2018).

Table 1: Three moral imperatives and key sustainability themes (source: Holden et al, 2018)

The three E’s are the three main interests that should be accounted for in the sustainability evaluation of a project. Consideration for the three E’s are therefore key in order to guide every developmental decision made in PIC’s projects.

Sustainable development is really an orientation, and not a destination. In his cultural history of sustainability, Ulrich Grober remarks that sustainability “is not a final goal to be achieved at some stage, but rather a compass providing orientation for a journey into an unknown future” (2015, p.15). Clarifying the correct understanding of the term helps to filter out confused usages by environmental conservationist and exploiters.

Impact Gaps Canvas

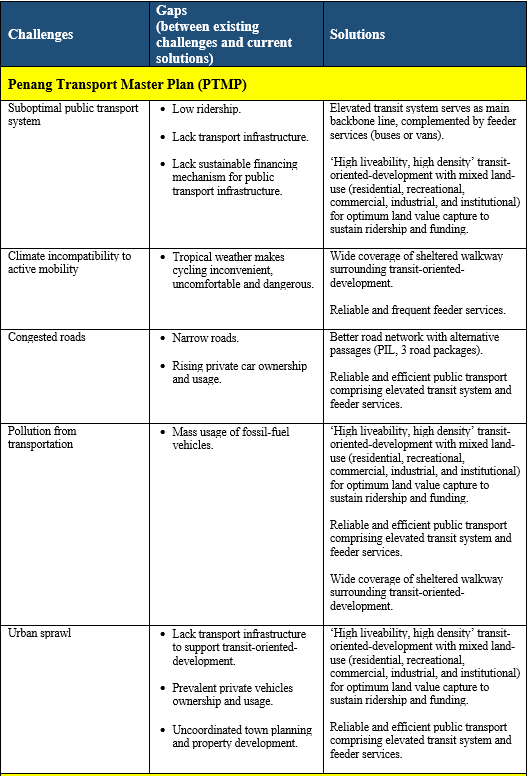

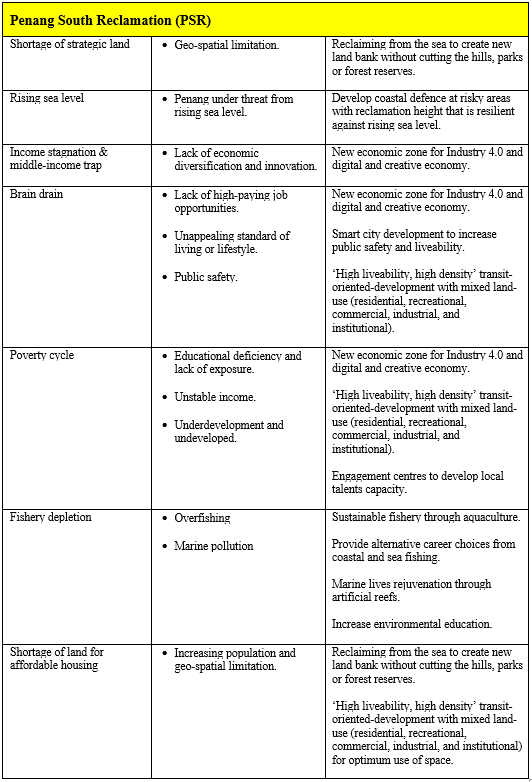

Impact Gaps Canvas enables us to highlight the sustainability challenges and gaps in Penang and the proposed solutions based on PIC’s projects. The table below is divided into two sections for PTMP and PSR respectively, with several listed solutions applicable to different challenges.

Table 2: Impact Gaps Canvas for PTMP and PSR

Impact Gaps Findings

As seen in Table 1, the PTMP and PSR are catalysts with targeted solutions to address the listed sustainability challenges and gaps facing Penang. It is also clear from the Table that the two projects converge as an infrastructural powerhouse for state-building, providing a long-term trajectory of socioeconomic development and sustainable urban growth.

The elevated transit system in PTMP, when complemented by first-mile-last-mile feeder services (bus, tram, or autonomous rail rapid transit) and personal mobility facilities (bicycle, personal transporter, sheltered walkway), will increase the appeal, convenience, and reliability of Penang’s public transport. Furthermore, as a sustainability strategy, the transit infrastructure is more than a mobility solution. Being the pivotal part of transit-oriented-development (TOD), the elevated system plays the catalytic role that reduces traffic congestion, optimises land usage, cuts carbon emissions, and increases liveability, as observed in Copenhagen, Hong Kong, and Singapore (Woo, 9 July 2020). Elevated transit system is a method time-tested for safety and reliability, and is used in many developed cities. The Asian Development Bank, a foremost authority that has implemented sustainable public transport all over the world, has recommended light rail system as the proven technology to be adopted for Penang (ADB, letter to Penang State Secretariat, January 30, 2020).

PTMP’s improvement of road networks with PIL and major road projects will serve the targeted 60% private vehicle users that are projected to rise along with population growth and increased capital flow. Although some questions were raised for the need of new roads in Penang (Tan et al, 30 July 2018; Hilmy, 1 June 2019), the complementary role of road expansion and public transport development effectively serving public mobility is empirical. The most obvious example is Hong Kong. The city’s public transport usage is over 90%, with less than 10% using private vehicles (Transport and Housing Bureau of Hong Kong, 2017). Hong Kong is probably the least car-dependent city. Nonetheless, the continuous growth of population and wealth increases the usage of both public transport and private vehicle. Besides upgrading their public transport, the expenditure for Hong Kong’s new highway and road projects is approximately RM45.5 billion, which includes Central-Wan Chai Bypass and Island Eastern Corridor Link, Central Kowloon Route, road expansion for West Kowloon Reclamation Development, Hiram’s Highway Improvement, and widening of Tolo Highway/Fanling Highway (Woo, 28 May 2019; 3 June 2019). The same complementary development is seen in Switzerland and Singapore. The former had RM7.4 billion allocated for various road projects in 2017 alone, while the latter budgeted RM502 million, excluding the RM23 billion North-South Corridor expressway (Woo, 31 July 2018).

The construction of the PTMP will be partly financed by proceeds from PSR, the development of the three islands at the south of Penang. The social and environmental aspects of PSR have been identified, studied, and addressed by the copious impact assessments and management plans, which include but are not limited to environmental impact assessment and management plans, hydraulic study, fishery impact assessment and management plans, social impact assessment and management plans, traffic impact assessment and management plans, and marine traffic risk assessment and management plans. The PSR on its own is a strategic endeavour conceived to ensure the wellbeing of Penang over the next five decades in view of present and upcoming socioeconomic challenges. The reclamation of 4,500 acres of land is a sustainability strategy to prepare Penang for the next stage of industrialisation, i.e. Industry 4.0.

Started as a port city, Penang enjoyed tax-free benefits until 1969 before the free port status was cancelled by the federal government. Penang’s economy was significantly affected, with unemployment shooting up to 20% (Moore, 2018, p.133). In 1970, many parts of Penang were paddy fields, and agriculture accounted for 20% of Penang’s GDP, more than the 13% contributed by the manufacturing sector. At that time, 44% of Penang’s population was living in poverty (Singh et al, 2019, p.181). In 1971, Penang’s GDP per capita was 12% below the national average (Nesadurai, 1991).

The early sustainability strategy adopted by Penang was based on recommendations in the Nathan Report (also known as Penang Master Plan Study, prepared by the US-based consultancy firm, Nathan Associates in 1970). The state’s economic outlook was changed from import-substitution to export-oriented industrialisation. One of the proposals stated in the Nathan Report was the shifting of the industrial location from Seberang Perai to Bayan Lepas, which had better logistic facilities such s the international airport. The Bayan Lepas area therefore came up as the natural choice to house the first Free Trade Zone in the state when the decision was made in January 1972. Paddy fields and coastal areas were reclaimed for that purpose. A preliminary study established that 3,800 hectares of land were possible for reclamation (Singh et al, 2019, p.72). Penang’s export-oriented economy is largely focused on electronics and electrical (E&E) manufacturing. The sector alone employs more than 300,000 workers and provides more than RM1.5 billion in salary payments every month in Penang (Mok, 23 April 2019).

Penang is responsible for supplying 8% of back-end semiconductor to the global market (Das & Lee, 9 March 2020). In 2016, Penang had the second highest GDP per capita in Malaysia. (FMT Reporters, 13 October 2017). By 2018, the agriculture sector accounted for only 2.2% of the state GDP, compared to manufacturing at 43.3% (Ong, 4 April 2020). The incidence of absolute poverty in 2019 was 1.9% (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2020). The past 40 years of industrialisation has transformed Penang from a backwater state into one of the top performing states in Malaysia. Based on 2017 statistics, Penang’s products had the highest average value created per worker (RM141,000), ahead of Selangor (RM124,200) and Johor (RM84,400) (Ong & Lee, 23 May 2020, p.3).

However, the inflow of foreign investment into Penang and job availability can be upended when the state remains in status quo while new economies emerge in the region. This happened in the early 2000s. When China joined the World Trade Organisation in 2001, the number of multinational corporations (MNC) in Penang fell to 23 in the period from 2000 to 2004, compared to 63 from 1990 to 1994. The number of MNC employments from 2000 to 2004 was 5,585, a 69% drop from 18,301 (1990-1994) (Kok, 2016, p.267). In the first three quarters of 2001 alone, Penang suffered a loss of 12,000 high-tech jobs (Balfour, 22 October 2001).

Rising industrialisation in neighbouring countries such as Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia is competing with Penang for E&E investment and jobs (Liew, 26 September 2019). Take Vietnam as example. The country’s economy grew at an impressive rate of 7% in 2019, surpassing their government’s target of 6.8%. Businesses have migrated to Vietnam as the country is becoming a safer and cheaper option for manufacturing. In the 2020 World Bank’s Human Capital Index, Vietnam was 24 rank positions above Malaysia (World Bank Group, 2020, p.27). The US News and World Report has listed Vietnam as the 8th best country for investment in 2019, and Malaysia as the 13th (Malaysiakini, 19 September 2019). The southeast Asian region has become much more competitive. Penangites are naturally migrating when offered better opportunities. More than 47,000 out-migration occurred in Penang from 2012 to 2016, contributing further to the state’s long-term brain drain (Penang Institute, Penang: Population and Demographics).

PSR is the sustainability strategy undertaken by the Penang State Government to address these various challenges and gaps. The location of PSR is astute. Proximity to the airport leverages on the global logistical network. More than 80% of E&E products are exported from the Penang airport (Athukorala & Narayanan, 2017, p.12). Electronic products such as Dell computers are deliverable from Penang to the US within 28 hours (Wahyuni et al, 2012, p.34). The existing E&E ecosystem surrounding the airport and the Free Industrial Zone is conducive for MNC and small-medium enterprises expansion. The Penang Skills Development Centre and the Collaborative Research in Engineering, Science and Technology Centre which are located near the industrial zone, provide talent support and research and development opportunity for the industry (Athukorala & Narayanan, 2017, p.13-14; Jacobs, 20 February 2019).

PSR has all these advantages that other projects in Penang do not have. It is estimated to create 300,000 jobs, support 24,000 small-medium enterprises, and generate RM70 billion for the state’s economic development for three decades (Lim, 18 December 2016; Tan, 16 April 2019; Penang State Government, 2019, p.6-14). Besides, the reclaimed islands will also contain residential and commercial areas to uplift the locals, especially the fishermen, out of the poverty cycle. The development will provide stable-income jobs, better public facilities and education opportunities. It will also undertake measures such as installation of artificial reefs and sustainable fisheries to deter overexploitation of marine resources or overfishing, and thus should lead to marine rejuvenation (Woo, 9 May 2020; 26 June 2019).

Conclusion

Penang is facing various sustainability challenges. By using the Impact Gaps Canvas, we have identified and analysed PIC’s ambitious undertakings as initiatives to address those challenges, ensuring the state’s wellbeing over the next 50 years by balancing economy, equity, and ecology – based on sustainable development principles. PTMP and PSR are sustainability strategies in Penang’s quest to strike the right balance between addressing human needs and the pursuit of ecosystem flourishing.

For list of references, kindly download the document to view.

Editor: Ooi Kee Beng

Editorial Team: Sheryl Teoh, Tan Lii Inn, Alexander Fernandez, and Nur Fitriah (Designer)

You might also like:

![Strengthening Preventive Measures against Child Sexual Abuse in Malaysia]()

Strengthening Preventive Measures against Child Sexual Abuse in Malaysia

![Food and Nutrition Security for Urban Low-income Households in Penang]()

Food and Nutrition Security for Urban Low-income Households in Penang

![Crafting Employment for Persons with Learning Disabilities is a Sound Socio-economic Stratagem]()

Crafting Employment for Persons with Learning Disabilities is a Sound Socio-economic Stratagem

![Fighting Covid-19 with Collaboration and Connectivity in Medical Science and Information Technology]()

Fighting Covid-19 with Collaboration and Connectivity in Medical Science and Information Technology

![Covid-19 in 2022: A More Optimistic Landscape Emerges]()

Covid-19 in 2022: A More Optimistic Landscape Emerges