Executive Summary

Introduction

In November 2016, homegrown motorcycle ride-hailing company Dego Ride started services at RM2.50, limited to three-kilometre trips around the Klang Valley[1]. Within two months, the government, then the Najib-led Barisan Nasional administration, banned the ride-hailing service[2]. Before it was banned, Dego Ride reportedly hired 1,500 mat motor (motorcycle riders) and attracted more than 60,000 users [3]. The reason for banning Dego Ride appears to be straightforward—safety. The Ministry of Transport pointed out that the likelihood of motorcyclists being involved in fatal accidents was 42.5 times higherthan for buses and 16 times higher than that for cars [4] Safety for women passengers was of particular concern, with religious reasons also being cited for not wanting women to use motorcycles for ride-hailing. To this point, suggestions were made. For example, other countries use a pink motorcycle version for women. On August 28, 2019, Dego Ride began offering users a free motorcycle ride each day. Just two days later, however, it temporarily ceased its motorcycle e-hailing service.

The resumption of operations in 2019 came after meetings between Gojek founder Nadiem Makarim, then-Youth and Sports Minister Syed Saddiq, then-Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, and Transport Minister Anthony Loke. Cabinet gave Gojek the green light to enter Malaysia’s motorcycle e-hailing industry, while Dego Ride was given the go-ahead to resume services on condition that they tighten several key safety aspects. For undisclosed reasons, Gojek eventually did not enter the Malaysian market.

On January 1, 2020, Dego Ride was back in operation under a six-month trial, limited to the Klang Valley, after obtaining special approval from Cabinet [5]. But the Covid-19 pandemic and the collapse of the Pakatan Harapan government after the Sheraton Move left the sector in limbo. By the end of 2021, Deputy Transport Minister Datuk Henry Sum Agong said the Transport Ministry had no plans to allow motorcycle ride-hailing, for safety issues [6]. Is safety truly the main reason for banning motorcycle ride-hailing in Malaysia, or a mere excuse, as some people, including Syed Saddiq, have alleged?[7]

The Case of Our Neighbours

Neighbouring Indonesia, also a Muslim-majority country, has a booming ride-hailing sector worth an estimated Rp 382.62 trillion (US$2.35 billion) or 2 per cent of Indonesia’s GDP in 2022 [8] There, motorcycles also account for the largest contributor to traffic fatalities at 81%, even higher than Malaysia’s 59%.9 Malaysia also has a motorcycle ownership rate per capita comparable to Indonesia’s, at 466 per 1,000 people [10] 83 per cent of households in Malaysia owning a motorcycle ranks the country fourth in Asia, trailing just behind Indonesia by two percentage points [11]. While Malaysia has a smaller population, it similarly faces problems of traffic congestions—Klang Valley workers spend at least 44 hours a month in traffic jams—a problem which the motorcycle can bypass [12]

Thailand also serves as a counterexample to Malaysia. Similar discussions on banning motorcycle taxis in the 1980s in Thailand eventually fizzled out as thousands of young rural migrants continued to buy motorcycles and transform them into sources of income, responding to the needs of a rapidly expanding metropolis, spreading faster than legislators’ decision making [13] In Malaysia, however, the actual ability to ban motorcycle e-hailing speaks to state power and control over urban spaces. Yet at the same time, the state is unable to provide sufficient connectivity-related infrastructure to adequately replace services deemed ‘unsafe’ by the government but a necessity for the everyday Malaysian.

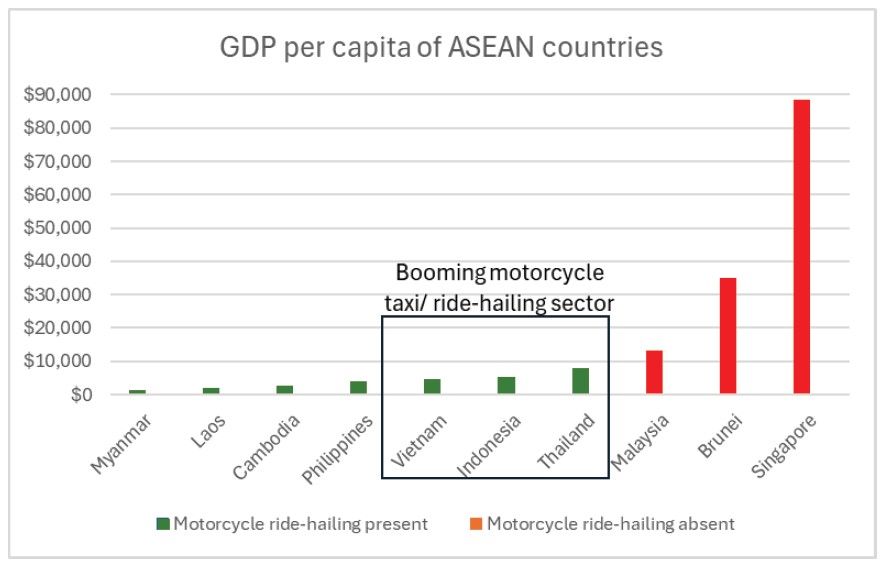

These cross-country comparisons cast doubt on the claim that safety concerns truly account for why motorcycle ride-hailing is banned in Malaysia. At the most basic level, the differences suggest that Malaysia has a dissimilar standard of and perception towards safety and risks compared to Indonesia and Thailand, perhaps correlated with its level of development.

SOME POSSIBLE UNDERLYING REASONS

A deeper dive into the evolving perceptions towards the motorcycle and its place in Malaysian society reveals some underlying reasons of which “safety” is a symptom and for which it serves as a convenient label. The criminalisation of illegal motorcycle behaviour in the past two decades, coupled with anxieties surrounding the lack of socio-economic mobility as a motorcycle rider, facilitated by Malaysia’s relatively strong state power in banning the sector, provide more compelling explanations as to why there is no motorcycle ride-hailing sector today. Taken together, the negative perceptions of motorcycles and aspirations towards socio-economic mobility (even at the expense of physical mobility) foster an association between motorcycles and danger. Safety concerns, then, is a product of these more fundamental reasons.

An examination of newspaper articles about motorcycles in Malaysia from the 1960s to the 2000s reveal a shift in perception towards the motorcycle from the early 2000s. While high fatality rates have been a concern since the 1960s, the narrative surrounding how to deal with the problem has shifted from finding ways to accommodate the presence of motorcycles to highlighting the risks that motorcycles pose to others. Efforts in the pre-2000 years include proposing that states have road safety councils in 1961, suggesting to educate students about road safety through a handbook in 1964, making crash helmets compulsory in 1973, and adding motorcycle lanes to newly constructed roads in 1997 [14]. The risk perception towards motorcycles had always been present; an article as early as 1965 for example was titled “1,000 will die on the road each year unless…”, raising awareness about the importance of wearing safety helmets [15]. Yet, while these articles over 40 years at times adopt a fearmongering tone, not once has the motorcycle itself been vilified. Instead, there were always additional measures to facilitate the presence of motorcycles on roads—helmets, additional lanes, safety councils and the like.

The narrative took a turn to one of vilification with the rise of the “Mat Rempit” (illegal racers) phenomenon since the 2000s [16] The Mat Rempit do not only perform stunts and speed on roads, but also partake in criminal activities. The motorcycle thus became associated with other forms of crime such as robbery and rape. It also became a symbol of affront to authority as the Mat Rempit regularly attacked the police and their property.17 Comments on online forums in recent years further indicate an association between motorcycles in general and Mat Rempit. For example, a comment which garnered 50 upvotes on reddit states “It has come to a point where I, a daily rider, are [sic] also being called a rempit.”18 This Mat Rempit phenomenon is not unique to Malaysia. In Indonesia the parallel phenomenon is Balap Liar (“wild racing”), comprising school leavers and university students who would prowl the streets on modified motorcycles.19 But the same level of criminalisation is not present. The solution in Indonesia: organise official street racing events to regulate such behaviour [20].

Indonesian police have since reported a decline in illegal street racing, while riders have suggested that they would stop illegal racing activities if there were more official races [21] The effects of criminalising an activity should not be underestimated. The state’s solution to the Mat Rempit does not take away social problems. Examples of intended solutions include heavier fines, license suspensions and vehicle confiscation [22] Online space was targeted too. In February 2007, it was announced that internet users who circulate sensitive news and pictures online, including clips of motorbike gangs performing stunts and motorists involved in illegal car racing, will be prosecuted for inciting unrest and taunting the police [23] These well-intended efforts are underpinned by the belief of creating safety. An operation last year, for example, was framed as “to prevent the scourge of mat rempits and street gangs, which frequently disturb public peace” [24] But instead of creating safety, the planned weekly police operations and persistence of Mat Rempit activity perpetuate the association between motorcycles and criminality.

Even so, the atmosphere of fear needs to be situated against the backdrop of aspirations of becoming something more than a motorcycle rider. Syed Saddiq, who had been an advocate for introducing motorcycle ride-hailing, shared some insights in an interview. Why was there an uproar among the population when he pushed to introduce Gojek as a motorcycle e-hailing service? People were not ready to accept being a motorcycle taxi driver as a panacea to unemployment—that was how the media framed the introduction of Gojek—despite it not being the intention.25

THE THRIVING GIG ECONOMY

At the same time, however, the size of the gig economy in Malaysia has been growing, reaching an all-time high of three million in 2023.26 Many fifth-form secondary students are opting for gig economy work instead of pursuing higher education, and 12 per cent of p-hailing workers, that is, food, drinks and parcel motorcycle delivery riders, are degree holders [27] The present reality, even with motorcycle ride-hailing banned, is precisely a manifestation of the feared future that led to the aforementioned uproar. This trend of a growing gig economy continues to spark fears about a shortage of skilled workers and stagnant wages. A deeper investigation into the short-lived story of Dego Ride thus provides a window into the many layers of “in-between” in which Malaysia is caught. Perceptions that motorcycle ride-hailing is “not the way to turn Malaysia into a developed nation” is illustrative of Malaysia’s wider economic position as one stuck in an upper-middle income trap [28]. Culturally, motorcycle riding is viewed through a patronising lens. Yet infrastructurally, the country is unequipped for the population to rely solely on public transportation. In terms of socio-economic mobility, people aspire to be more than a motorcycle rider, but reality proves otherwise, with the size of the p-hailing sector growing over time. Malaysia has the right conditions to support a motorcycle ride-hailing sector—high motorcycle ownership, limited public transportation infrastructure which can be complemented with motorbikes for last-mile connectivity, the presence of a p-hailing sector performing delivery services, among others. The alternatives, a Grab car or walking, are often unfeasible.

The former is costly and passengers are subject to being stuck in immense traffic—for example a two-kilometre stretch can take 15 to 20 minutes and cost as much as RM 20—which defeats the purpose of making public transportation accessible; the latter is not a real alternative because there are not enough covered walkways, especially in the sweltering heat or when there is bad weather [29] With the increasing share of the gig economy, it is worth asking why motorcycle ride-hailing, a booming sector in other

Southeast Asian countries, is still banned.

Given the vibrant p-hailing sector, motorcycle ride-hailing presents untapped opportunities. Arrangements like motorcycle riders offering ride-hailing services during peak hours and delivery services in between, as Syed Saddiq suggested, are worth looking into. Without such an ecosystem, the largest losers of the p-hailing sector at present are small businesses, with food delivery currently limited to larger restaurants. The possibilities offered by introducing motorcycle ride-hailing could further support gig economy workers and expand growth opportunities for small businesses. More importantly, in contrast to Grab car services, two-wheeler ride-hailing service is a complement to public transport, as it boosts last-mile connectivity. During my fieldwork in Indonesia, for example, a common suggestion heard from locals was to take a Gojek or Grab bike to and from MRT stations as a last-mile option to beat the traffic. Having an effective two-wheeler ride-hailing sector could drive up usage of public transport in Malaysia, as more people would be willing to leave their cars behind, or switch from car-based transport. Such behavioural change would help move Malaysia towards its goal of achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, especially as the transport sector has been identified as a key contributor to carbon emissions [30]. The question, then, is how legislators can work to overcome the deep-seated socio-cultural reasons outlined above which contribute to the short-lived presence of two-wheeler ride-hailing and long-standing ban being in place. But for now, a good part of the population, especially those in Klang Valley, remains stuck in traffic [30].

[1] https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/505567 [2] https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2019/08/24/govt-will-help-push-local-player-dego-ride-too-says-syed-s

addiq/ [3] https://malaysia.news.yahoo.com/jek-youth-minister-meets-boss-064507258.html [4] https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2019/08/24/govt-will-help-push-local-player-dego-ride-too-says-syed-s

addiq/ [5] https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/505567 [6] https://www.thevibes.com/index.php/articles/news/47259/syed-saddiq-slams-henry-for-sloppy-answer-on-m-cycle-e-hailing [7] https://www.thevibes.com/index.php/articles/news/47259/syed-saddiq-slams-henry-for-sloppy-answer-on-m-cycle-e-hailing [8] “SBM ITB Researchers Released Findings on Ride Hailing Industry 2023,” https://www.sbm.itb.ac.id/2023/09/22/sbm-itb

-researchers-released-findings-on-ride-hailing-industry-2023/#:~:text=The%20research%20found%20that%20the,GDP%20(

Rp%2019%2C588.4%20trillion).

Average monthly spending on online motorcycle taxi services can be found here https://www.statista.com/statistics/

1377964/indonesia-monthly-spending-on-online-motorcycle-taxi/.

https://vietnamnews.vn/economy/1652076/vn-s-ride-hailing-expected-to-reach-us-2-16-billion-by-2029.html#:~:text=H%C3

%80%20N%E1%BB%98I%20%E2%80%94%20Vi%E1%BB%87t%20Nam’s%20ride,market%20research%20firm%20Mor

dor%20Intelligence. [9] Kardina N.S Ayuningtyas et al, “Addressing Indonesia’s biggest road safety challenge: Reducing motorcycle deaths,” 2024

IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 1294 012013. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1755-1

315/1294/1/012013/pdf#:~:text=Among%20all%20road%20users%20in,not%20have%20a%20motorcycle%20license.; [10] https://www.nst.com.my/news-cars-bikes-trucks/2023/04/901069/59-cent-malaysian-road-fatalities-involved-motorcyclists. [11] https://aaa.fourin.com/reports/946c9ea0-165b-11ee-8711-170a5bff50d0/asias-ownership-volume-of-motor-vehicles-in-2022 [12] https://seasia.co/infographic/the-highest-motorcycle-ownership-rate-in-asia-2023 [13] https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2022/06/809243/klang-valley-employees-spend-44-hours-month-sitting-traffic

Claudio Sopranzetti, Owners of the Map: Motorcycle Taxi Drivers, Mobility, and Politics in Bangkok, 34. [14] “States to have road safety councils,” Nov 1961, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes

19611128-1.2.65.; “Educating students about road safety through a handbook,” Jun 1964, https://ereso

urces.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19640619-1.2.123.; “Discussions on making safety helmets and

seatbelts compulsory,” Aug 1964, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19640825-1.2.94.

Nov 1964: Road toll in 9 years: 3,855 dead, 54,000 injured, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/st

raitstimes19641120-1.2.88.9. [15] “1,000 will die on the road each year unless…”, The Straits Times, 27 April 1965, Page 6 April 1965,

https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19650427-1.2.39 [16] See for example https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/beritaharian20070403-1.2.13.4?qt=mat,%

20rempit&q=mat%20rempit, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes20071014-1.2.5.13?q

t=mat,%20rempit&q=mat%20rempit [17] “They attack police station with rocks,” The New Paper, 18 October 2006, https://eresources.nlb.gov

.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/newpaper20061018-1.2.7.3.1?qt=mat,%20rempit&q=mat%20rempit.;

“20 ‘Mat Rempit’ rompak pengurus”, Berita Harian, 31 October 2006, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg

/newspapers/digitised/article/beritaharian20061031-1.2.14.3?qt=mat,%20rempit&q=mat%20rempit.; “Mangsa seks ‘Mat

Rempit’”, Metro Daily, 13 December 2006, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/beritaharian

20061213-1.2.15.1.2?qt=mat,%20rempit&q=mat%20rempit. [18] https://www.reddit.com/r/malaysia/comments/zikfnu/the_rise_of_mat_rempit_culture/ [19] https://indonesialogue.com/about-indonesia/mat-rempit-woes-in-jakarta.html [20] https://www.channelnewsasia.com/asia/indonesia-jakarta-illegal-motorcycle-racing-police-sports-3351201 . [21] Tackling illegal street racing in Jakarta, Indonesia, CNA, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t4YXGuf09uU [22] “Hukuman lebih berat bagi pelumba haram,” Berita Harian, 17 October 2006, https://eresources.nlb

.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/beritaharian20061017-1.2.14.1.1?qt=mat,%20rempit&q=mat%20rempit. [23] “M’sia tightens grip on use of Internet,” 27 February 2007, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/

today20070227-2.2.14.4?qt=mat,%20rempit&q=mat%20rempit [24] https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2023/09/17/penang-police-seize-34-motorcycles-in-ops-on-suspected-mat-re

mpit-gangs/91373

You might also like:

![Urgent Need to Strengthen Malaysia’s Legal Framework Against AI-Driven Scams]()

Urgent Need to Strengthen Malaysia’s Legal Framework Against AI-Driven Scams

![Challenges and Opportunities for Penang’s Labour Market amid the Covid-19 Pandemic]()

Challenges and Opportunities for Penang’s Labour Market amid the Covid-19 Pandemic

![Malaysia’s Northern States: Improving Competitive Advantages and Industrial Growth]()

Malaysia’s Northern States: Improving Competitive Advantages and Industrial Growth

![George Town Heritage Celebrations: Achievements and Reflections]()

George Town Heritage Celebrations: Achievements and Reflections

![Survey on Attitudes to Covid-19 Vaccination in Penang]()

Survey on Attitudes to Covid-19 Vaccination in Penang