EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

• Policymaking and implementation have traditionally been viewed from a top-down public administration model. This results in an overemphasis on the role of political leaders in the success or failures of policies. In reality, political leaders have little influence over any significant portion of actors in the policy arena.

• The case of Penang’s sourcing for an alternative source of raw water is used in this article to highlight the realities of contemporary policymaking and implementation and how the policy arena involves social complexities and multiple actors interacting in a dynamic and turbulent manner to influence each other.

• A new model for policymaking and implementation from a network governance perspective is herewith proposed. From this perspective, policymaking and implementation are visualised as a polycentric network of interdependent actors interacting within a dynamic and often turbulent environment.

• This perspective further suggests that there is as yet much room for improving the effectiveness of policymaking and implementation in general. Particularly, questions around accountability, coordination and governance become strongly pertinent.

Introduction

For a large part of the twentieth century, policymaking and implementation have been viewed within a top-down public administration model, with political masters exerting control over an apolitical bureaucracy. This has led to an overemphasis on the role of the political class in the success or failures of policies. We see for example, how the Penang Chief Minister was immediately questioned by the media on an occasion when a car had plunged off the Penang Bridge, despite having little to no jurisdiction over the matter [1].

This model has indeed been questioned for its limitations and for contributing to policymaking in an increasingly fragmented, complex, and inter-organisational environment (Rhodes, 1997). Scholars has in recent times ben arguing for a new approach, one where policymaking and implementation are considered within a polycentric network of interdependent, multi-actor cooperation interacting in a dynamic and often turbulent environment (Keast, 2014).

The case of Penang’s sourcing for an alternative source of raw water is used in this article as an illustration to highlight the realities of policymaking and implementation. Two observations are discussed: (a) the involvement of multiple actors in the policy arena; and (b) the continual interactions among actors in the policy arena.

The paradigm of network governance is then introduced, arguing for policymaking and implementation to be viewed from a network governance lens, i.e. policymaking and implementation as a process of governing a web of autonomous yet interdependent actors. Using a network governance lens, the social complexity and agency of multiple actors in contemporary policymaking and implementation is better recognised.

Penang’s Water Woes

The State of Penang relies on the Muda River as a source for more than 80% of its raw water, projecting to meet demand only until the year 2025. This has prompted the Penang State Government, via Perbadanan Bekalan Air Pulau Pinang (PBAPP) to source for alternative water sources while advocating for the preservation of Muda River as a source of raw water [2].

The Muda River, a greater portion of which flows through the State of Kedah, has in recent times been a source of conflict between the two State governments. PBAPP has expressed concerns over the risk of pollution to Muda River, citing ‘triple threats’ to Penang’s water supply – logging in Ulu Muda, the proposed development of Kulim airport and aerotropolis adjacent to Sungai Muda, and rare earth elements mining in Ulu Muda [3]. Kedah, however, perceives such projects as justified for its own economic development.

Negotiations over the preservation of Muda River has reached an impasse, with the Penang State Government turning to the National Water Council (NWC) for assistance. A Federal-funded Ulu Muda Basin Authority was proposed to protect and manage the basin which serves three northern states [4]. The NWC, a council of the Federal Government however, functions merely as a deliberative platform between the Federal and State Governments on matters related to water resources; it has little to no coercive powers, given that water and land are a matter under state jurisdiction.

Concurrently, the Penang State Government has also identified Sungai Perai in Penang as a possible alternative source of raw water. Sungai Perai however has been plagued by industrial affluents, livestock and raw sewerage pollution, making conventional technologies insufficient for rendering its waters useable [5]. Meanwhile, addressing these sources of pollutants is in a state of quandary. Industrial waste falls under the purview of Department of Environment; sewerage under Indah Water Consortium, poultry and livestock waste under Department of Veterinary Services, while Local Councils oversees general health and safety of all premises which are licensed in Penang. In each instance, the Penang State Government has no direct authority over these agencies but primarily rely on implicit authority through State Enactments to direct and empower these agencies.

PBAPP also initiated the Sungai Perak Raw Water Transfer Scheme (SPRWTS) in 2009 which seeks to source water from the State of Perak [6]. Since its proposal, the Perak State Government has swayed between a “yes” and a “no”; on one hand citing their unwillingness to share its water to safeguard their own consumption while on the other hand proposing to sell treated water instead of raw water to Penang [7]. At the Federal level, the plan received approval by the National Water Service Commission (SPAN) in 2012 but the implementation of this was interrupted by the change in Federal Government in 2018 [8]. Consequently, two ministries were referred to; the Ministry of Environment and Water for a ministry-funded engineering study of the SPRWTS projects, and the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources to study Sungai Perak’s ability to meet water demand [9]. Only after 14 years of negotiations has an agreement now been made where the State of Perak will sell treated water to Penang. This can possibly end Penang’s water woes for a time [10].

Observations on policymaking and implementation

1. The policy arena consists of multiple actors from different institutional backgrounds, each playing a different role and contributing a different resource.

In the case above, we see the representation of a variety of actors, spanning the vertical levels (federalism) and horizontal length (agentification) of governments. Owing to their institutional background and roles, each actor is guided by different rules, outlooks and organisational arrangements such that all of them may be uncertain as to which processes are actually necessary (Klijn & Koppenjan, 2015). The involvement of two separate federal ministries in 2022 is one such case, which begs the question whether this was necessary, or merely a good-to-have.

Corollary to this, Penang’s water woes, while primarily affecting Penang, could not be solved by the Penang State apparatus in isolation. Rather, the resources of a variety of actors were needed, reflective of wicked problems that modern governments need to address (Choy, 2024). Penang’s Chief Minister embodied this “I have had meetings with two different ministers and two Menteri Besar, and finally, now, at the state secretary level in both states, the discussions will continue”, in a media statement on the matter [11]. The same is observed with addressing pollutants in Sungai Perai, and how this requires the resources of multiple actors.

Indeed, policymaking and implementation require the involvement of multiple actors, often cutting across existing demarcations and conventional hierarchies.

2. Policymaking is made through repeated rounds of interactions with actors constantly trying to influence others while tweaking their strategies in response.

From a policy stance of “yes” and “no”, the recent agreement by the Perak State Government to sell treated water best illustrates the dynamics of influencing and counter-influencing in a policy arena. This is particularly so in this case where we see a change in policy stance despite the same Menteri Besar serving throughout the negotiations over the past four years. This is contrary to traditional notions of policymaking where the political class, aided by apolitical public managers make rational decisions to maximise efficiency (Osborne, 2010).

Another dimension of interactions is also observed, one where policy actors dynamically update their strategies. We see for example how Sungai Perai as an alternative raw water source faded into the background despite the issue being repeatedly discussed in the State Legislative Assembly from 2021. Also, the Penang State Government begun negotiations with Perak for the purchase of raw water, but later changed its stance to purchase treated water instead [12].

We observe that the process of policymaking and implementation is dynamic, and in some ways, turbulent, where strategies are updated and chosen through repeated rounds of interactions among policy actors.

Towards a network governance model

The above observations, which are reflective of contemporary policymaking and implementation in practice, are of the type that have motivated public administration scholars to view these activities from a network perspective, teasing an imagery of a system of nodes connected through a web of relationships. Klijn & Koppenjan (2015) describes this as “public policymaking, implementation, and service delivery through a web of relationships between autonomous yet interdependent government, business, and civil society actors”. This is in contrast to policymaking and implementation as a sequential process delivered by disaggregated actors with linear interactions.

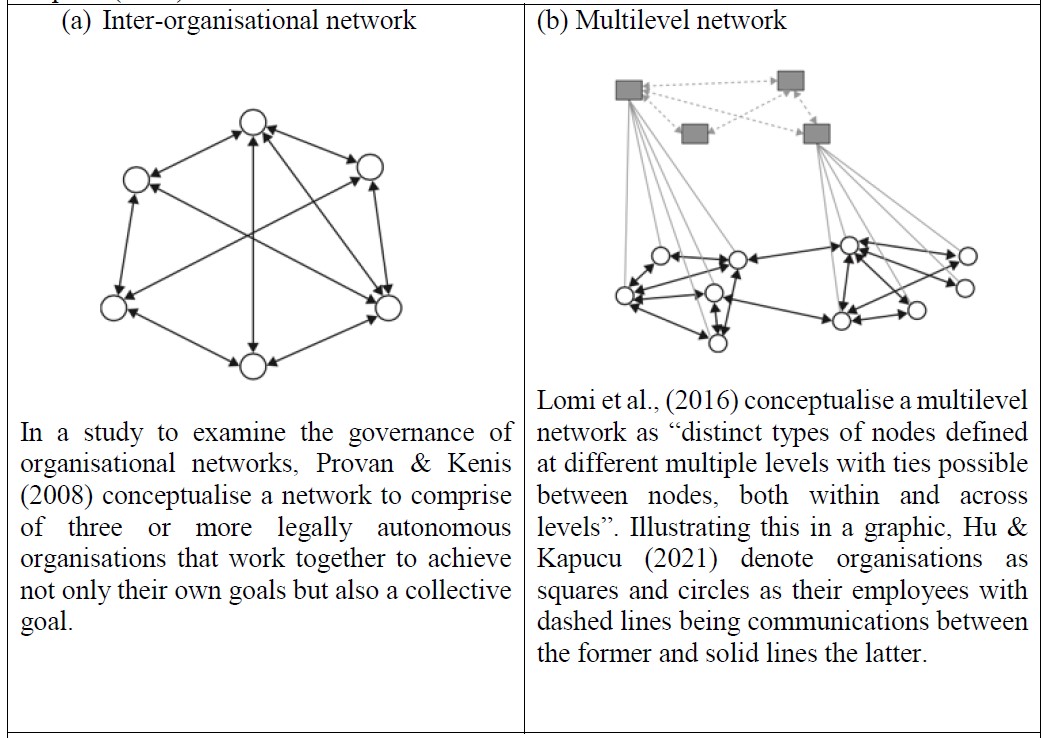

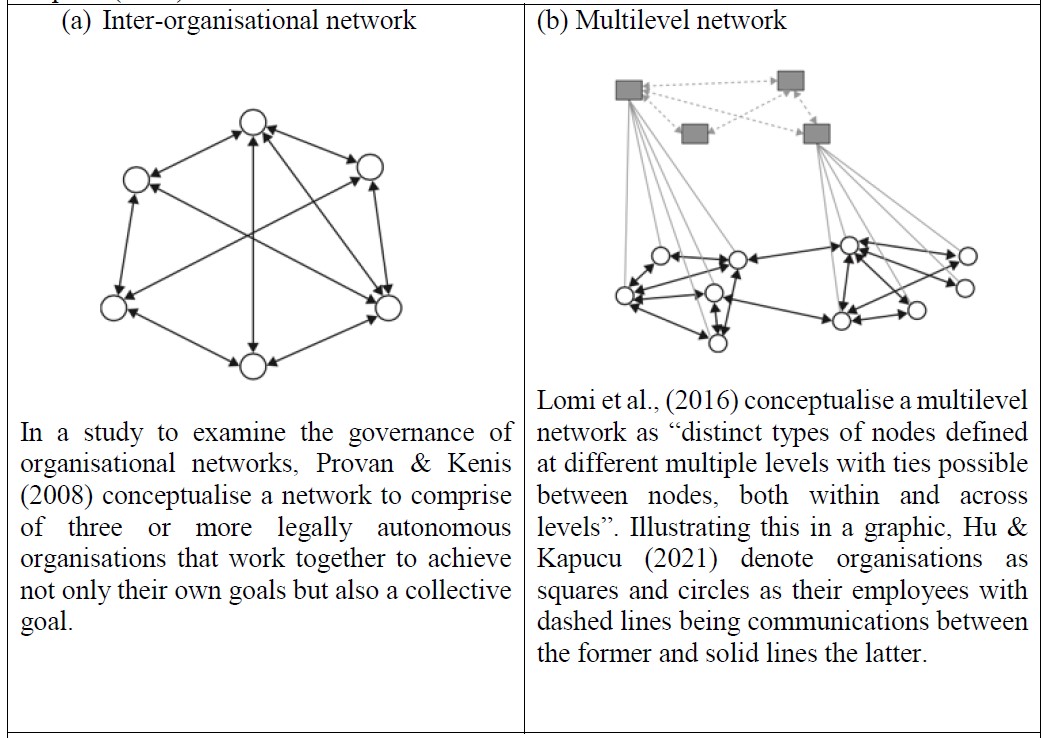

The use of networks has in fact been instrumental in better explaining contemporary policymaking. This is primarily due to their explanatory power to accommodate multiple levels or units of analysis, which at their most basic level, consists of a set of actors or nodes linked by a set of ties (see Figure 1-a). From a distinctly public sector perspective, nodes can represent individuals, organisations work units, or any other form of social categories (see Figure 1). Ties on the other hand can represent a wide range of relationships including information flow, resource exchange, and other forms of interactions; varying with the changing representation of nodes (Medina et al., 2022).

Concomitantly, this perspective has also been extended as a new paradigm to describe the regime of these activities and the organisation of their actors, that is to say, one of governing as opposed to the older paradigm of managing. The former carries elements of steering by actors within the network aimed at influencing interactions, while the latter exhibits elements of hierarchical command-and-control through competition mechanisms aimed at producing wished-for outcomes (Xu et al., 2015).

Together, network governance as a model for contemporary policymaking and implementation recognises the social complexity and agency of multiple actors in policy arenas today. This shift suggests that multiple resource-bearing actors are necessary, with each possessing some level of autonomy to release resources they command.

Conclusion

The case is made for using a model of interdependent polycentric networks in understanding policymaking and implementation. This argues that traditional top-down models are no longer realistic depictions in policy arenas, given how contemporary policy issues and structures of governments have evolved.

Considering this, further questions arise relating to policy networks. For one, the question of accountability becomes apparent. If policymaking and implementationare practised in a network, how does one attribute accountability fairly? Other questions on internal coordination and governance of policy networks also surface. In these, further research by the public policy community is called for.

It suffices to conclude that while political leaders are always expected to answer for almost every policy outcomes, rarely are they in a position with adequate influence – what more control – over any significant portion of that network.

Figure 1 – Various representations of networked-government are possible following the interchangeable nature of nodes to represent different actors. Graphics adapted from Hu & Kapucu (2021).

Bibliography

Eppel, Elizabeth. A., Rhodes, Mary. L., & Gerrits, L. (2021). Complexity in Public Management: Perspectives, Institutions, and Practices. In Handbook of Public Administration (4th ed.). Routledge.

Hu, Q., & Kapucu, N. (2021). Multilevel Network Governance in Emergency Management. In Handbook of Public Administration (4th ed.). Routledge.

Keast, R. (2014). Network Theory Tracks and Trajectories: Where from, Where to? In Network Theory in the Public Sector: Building New Theoretical Frameworks. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Network-Theory-in-the-Public-Sector-Building-New-Theoretical-Frameworks/Keast-Mandell-Agranoff/p/book/9781138617995

Klijn, E. H., & Koppenjan, J. (2015). Governance Networks in the Public Sector (0 ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315887098

Lomi, A., Robins, G., & Tranmer, M. (2016). Introduction to multilevel social networks. Social Networks, 44, 266–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2015.10.006

Medina, A., Siciliano, M. D., Wang, W., & Hu, Q. (2022). Network Effects Research: A Systematic Review of Theoretical Mechanisms and Measures. The American Review of Public Administration, 52(7), 513–528. https://doi.org/10.1177/02750740221118825

Osborne, S. P. (2010). The (New) Public Governance: A suitable case for treatment? In The New Public Governance?: Emerging Perspectives on the Theory and Practice of Public Governance. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/The-New-Public-Governance-Emerging-Perspectives-on-the-Theory-and-Practice-of-Public-Governance/Osborne/p/book/9780415494632

Provan, K. G., & Kenis, P. (2008). Modes of Network Governance: Structure, Management, and Effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(2), 229–252. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum015

Rhodes, R. A. W. (1997). Understanding Governance: Policy Networks, Governance, Reflexivity and Accountability. Open University Press.

Xu, R., Sun, Q., & Si, W. (2015). The Third Wave of Public Administration: The New Public Governance. Canadian Social Science, 11(7), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.3968/%x

Footnotes

[1] Mok, O. (2019). Penang CM wants study on crash barriers after car plunges into sea. Malay Mail.

[2] Dermawan, A. (2019). Penang needs to source raw water from Sungai Perak by 2025. New Straits Times.

[3] https://pba.com.my/raw-water-risks/

[4] Penang State Assembly Debate Volume 14 Page 24 (2021, December 3). Hansard.

[5] Penang Green Agenda 2030: Water and Sanitation. (2020). Penang Green Council

[6] Penang State Assembly Written Replies Volume 14 Column 26 (2021, August 30 to September 2).

[7] Mat Arif. Z (2022). No to supplying water to Penang, says Perak MB. New Straits Times.

[8] https://www.buletinmutiara.com/exclusive-six-day-water-disruption-in-penang-explained-part-two/

[9] Penang State Assembly Written Replies Volume 14 Column 50 (2021, November 26 to December 3).

[10] Dermawan, A. (2023). Penang CM: No need for water treatment plant in Penang for Sungai Perak water transfer scheme. New Straits Times.

[11] Mok, O. (2023). Penang considers taking treated water from Perak, discussions on water transfer scheme continues. Malay Mail.

[12]The Sun (2023). Perak govt proposes new WTP to meet water needs of northern Perak, Penang.

You might also like:

![Interracial Marriages Getting Popular in Malaysia: Government Support Would be Welcomed]()

Interracial Marriages Getting Popular in Malaysia: Government Support Would be Welcomed

![ESG Disclosures among Public-listed Companies Based in Penang]()

ESG Disclosures among Public-listed Companies Based in Penang

![Realising Blue Economy Benefits in Penang]()

Realising Blue Economy Benefits in Penang

![Protecting Women: An Overview of Women’s Legal Rights in Southeast Asia]()

Protecting Women: An Overview of Women’s Legal Rights in Southeast Asia

![Perbandingan Hukuman Hudud untuk Kesalahan Sariqah dan Hirabah di Brunei, Aceh, Kelantan dan Terengg...]()

Perbandingan Hukuman Hudud untuk Kesalahan Sariqah dan Hirabah di Brunei, Aceh, Kelantan dan Terengg...