Penang’s Socio-economic Transformation: Progress and Challenges

By Muhammed Abdul Khalid [1]

Executive Summary

- Since Malaysia’s independence in 1957, Penang has experienced remarkable progress, with its GDP per capita rising from RM4,739 in 1970 to RM69,684 in 2023, achieving an impressive 5.0% annual growth rate, surpassing the national average over the same period.

- Although absolute poverty has been virtually eliminated, relative poverty is still relatively high, and affects at least 1 out of 10 households in Penang. Penang will be the first state in Malaysia to have an aged population, and the state is not yet sufficiently equipped to manage these demographic changes. The state will need to place more emphasis on age-related policies in order to sufficiently meet the demands of an ageing population in the future.

- Penang also depends more on private healthcare than public healthcare, with data showing that the highest utilisation of private outpatient healthcare in Malaysia was in Penang, at 67.2 per cent, followed by Selangor (48.1 per cent) and Kuala Lumpur (48 per cent) (IKU, 2020). Penang’s development is also dependent on its ability to mitigate risks from its urbanisation, and from climate change. There is an urgent need for Penang to increase its capabilities and capacities to compete with other cities in the region.

- Another challenge for Penang is to ensure that growth is inclusive, and there is upward mobility for all. However, while income growth is positive, cost of living is becoming a serious issue.

-

Introduction

Penang has progressed remarkably since Malaysia achieved its independence in 1957. Its GDP per capita increased from RM4,739 in 1970 to RM69,684 in 2023 with an impressive annual growth of 5.0 per cent, higher than the national average during the same period. In fact, Penang attained upper middle-income status in 1986, and became a high-income state in 2012. If Penang is a country, its GDP per capita is roughly on par with that high-income economies such as Poland, Hungary, Portugal, and Romania.

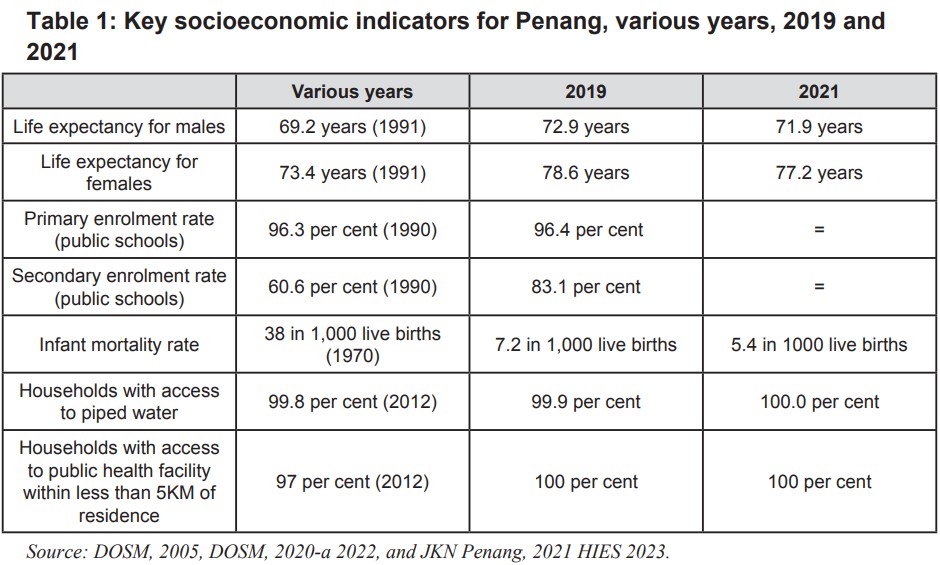

Its socioeconomic wellbeing in general also improved. Life expectancy, school enrolment rates, mortality rates and access to basic services progressed significantly (Table 1). In the past three decades, life expectancy in the state increased by about 3 years for males and 5 years for females, with almost universal access to water and utilities, and extensive affordable public healthcare facilities. Infant mortality rates dropped significantly, from 38 per 1,000 live births to 7.2 in the past five decades. Enrolment in primary education and secondary education have also improved.

Penang’s key socioeconomic indicators such as median household income, life expectancy, and infant mortality rate are also better than the national average. The state, not unlike other richer states such as Kuala Lumpur, Johor or Selangor, benefited from better infrastructures, higher domestic and foreign investments, as well as relatively higher federal funding and investment compared to other states (EPU, 2020).

Penang also performed relatively better based on the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)’s Human Development Index (HDI) and is considered to have ‘very high’ human development. The HDI has three dimensions, which are health, education, and standard of living, measured by 1) life expectancy at birth, 2) expected years of schooling and mean years of schooling, and 3) gross national income (GNI) per capita (UNDP, 2022). In 2022, Penang’s HDI was 0.836, which is higher than Malaysia’s HDI (0.803), and comparable to countries like Qatar (0.848) and Chile (0.851) (Global Data Lab, 2022, and UNDP, 2022).

Malaysia’s achievement in poverty eradication and narrowing income gap is well noted, and Penang is no exception. The absolute hardcore poverty rate in Penang, measured using the national poverty line income, dropped from 43.7 per cent in 1970 to 4.0 per cent in 1992, and further reduced to 0.1 per cent in 2022.Although the poverty line income (PLI) was revised in 2019, the trend remains the same, the absolute poverty in Penang has decreased from 2.2 in 2016 to 2.0 in 2022. Hardcore poverty has also been almost eliminated. The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) of Penang, which includes non-monetary measurements of poverty such as access to education and other amenities, has also improved (DOSM, 2020-c). Meanwhile, inequality, measured by the Gini coefficient, also narrowed during the period, dropping from 0.597 in 1974 to 0.371 in 2022. Penang’s absolute poverty rate and Gini coefficient performed better than the Malaysian average.

Although overall poverty has almost been eliminated, there are still pockets of poverty in the state. In 2022, the highest incidence of absolute poverty is in the Seberang Perai Utara district, at 3.7 percent (the lowest incidence is in the Timur Laut district on the Penang Island, at 0.7 per cent. Penang’s economic expansion also translated into increased household income. Median household income increased from RM1,693 in 1995 to RM6,502 in 2022, or at an annual growth rate of 5.5 per cent over the same period. All ethnic groups experienced positive income growth.

The population in Penang grew exponentially, from around 776,000 persons in 1970 to 1.74 million persons in 2020 (DOSM, 2022-a). Part of this expansion is due to its initial popularity as an internal migration destination in the country (National Higher Education Research Institute, 2010). Penang is also highly urbanised, with 92.5 per cent of its population residing in urban areas in 2020 (DOSM, 2022-b). While the population grew, the average household size has also shrunk from 5.8 in 1970 to 3.5 persons per household in 2020 (DOSM, 2022-b), contributed mostly by the declining fertility rate.

In fact, Penang has the lowest fertility rate in the country, with 1.3 babies per women, below the replacement rate of 2.1, and below Sabah (1.4), Kuala Lumpur (1.5) Sarawak (1.6), and the national average of 1.8. All ethnic groups show a fertility rate below the replacement rate, including among the Bumiputera who register a total fertility rate at 1.7, compared to Indians at 1.2, and Chinese at 1.0.

-

Ageing and Demographic Changes

Penang is currently an ageing state, with the share of older persons (aged 65 and above) steadily increasing in the past few decades, rising from 3.5 per cent in 1970 to 9.4 per cent in 2021, higher than the national average of 7.4 per cent. Meanwhile, the share of those aged below 15 has been decreasing more rapidly, from 41.1 per cent in 1970 to 19.3 per cent in 2022. The proportion of the working age population (15 to 64 years) has increased from 55.6 per cent in 1970 to 73.3 per cent in 2022 (DOSM, 2021-a). Penang has the second highest median age out of all Malaysian states, at 32.7 years in 2021, behind that of Kuala Lumpur (34.0 years). Penang’s median age is higher than the global median age of 31.0.

Penang’s ageing population is a result of higher life expectancies and falling fertility rates (as explained earlier), which is in line with the national trend. Life expectancy in Penang has increased from 74.5 years in 2011 to 76.1 years in 2021. Penang’s life expectancy is comparable to that of Hungary and Kuwait. Females live longer than males, at 78.9 years and 73.5 years in 2021 respectively – the female life expectancy is comparable to countries such as Hungary and the UAE.

By 2030, Penang is expected to reach an ‘aged’ status, the only state in Malaysia where the share of those aged 65 and above will be at 14 per cent or more. In 2012, the share of population aged 65 and above stood at 7 per cent. By 2040, 1 in 5 of Penang population will consist of old individuals, the highest compared to other states in the country.

Due to demographic changes, the dependency ratio [2] in Penang is projected to continue increasing, from 41.6 in 2010 to 56.2 by 2040. In other words, the number of young working population to support the elderly population will decrease, and the overall economy will face a greater burden in supporting and providing the social services needed by children and older persons. An ageing population will have several serious implications on the sustainability of economic growth, in particular on fiscal resources, labour market, as well as on income security and aged care (World Bank, 2020). It is worth noting that older persons are also more vulnerable to poverty and economic shocks, especially those who are frail and in need of aged care and long-term care services.

Although Penang has done relatively well in the past, several challenges remain.

Challenges

Although absolute poverty has been virtually eliminated, relative poverty is still relatively high, and affects at least 1 out of 10 households in Penang. The relative poverty in Penang has increased to 15.3 percent in 2022, an increase of 2.1 percentage points from 2019, which almost mirrors the national trend. Inequality has also risen during the same period, with the Gini coefficient rising slightly from 0.356 to 0.371. The rise in inequality is sharper in the administrative districts of Barat Daya and Seberang Perai Tengah compared to other districts.

Given that Penang will be the first state in Malaysia to have an aged population, the state is not yet sufficiently equipped to manage these demographic changes. It will need to place more emphasis on age related policies to handle these changes. For instance, while access to public healthcare facilities is almost universal, there is not enough public medical doctors in the state. The 12th Malaysia Plan set a target of having one doctor to serve 400 patients (EPU, 2021). However, Penang’s doctor to population ratio stood at 684, which is even lower than poorer states such as Kelantan, Terengganu, and Pahang (DOSM, 2020-f).

Similarly, public hospital beds in Penang are insufficient to meet the needs of the population. There is one public hospital bed per 1,000 population, much lower than the optimal two hospital beds per 1,000 population stated in the 12th Malaysia Plan The number of beds per population in Penang is among the lowest in the nation, only second last to Selangor. Sarawak and Sabah and East coast states like Kelantan and Terengganu have better capacities than Penang. In fact, there are not enough public hospital beds in all districts in Penang, except Timur Laut (George Town). The district which is in dire need of hospital beds is Barat Daya, followed by Seberang Perai Utara (Butterworth).

Penang also depends more on private healthcare than public healthcare, with the data showing that the highest utilisation of private outpatient healthcare was in Penang, at 67.2 per cent, followed by Selangor (48.1 per cent) and Kuala Lumpur (48 per cent) (IKU, 2020). At the same time, Penang has the highest percentage of the population who could not afford personal health insurance, at 52.6 per cent (IKU, 2020). Penang’s out-of-pocket (OOP) per capita health expenditure was also higher than Malaysia’s, at RM930 in 2019, compared to the national average of RM680. Furthermore, Penang’s per capita health expenditure for inpatient healthcare is the highest in Malaysia, at RM304, compared to the Malaysian average of RM50.

Penang’s development is also dependent on its ability to mitigate risks from its urbanisation, and from climate change. Extreme flood events are more likely in areas with high urbanisation, and the state government has announced in June 2022 its intentions to upgrade its flood mitigation infrastructure (Nambiar, 2022). However, the impact of these efforts on flood mitigation may be limited since the latest phase of the project would only reduce the risk in a 7km2 area out of the overall 51km2.

There is an urgent need for Penang to increase its capabilities and capacities to compete with other cities in the region in attracting quality foreign direct investments. There are several challenges facing Penang at the moment in its dominant electrical and electronics (E&E) sector, such as shortage of skilled talent, easy access to low-skilled foreign labour which has discouraged innovation, local R&D activities, and back-end manufacturing activities which are low in value-added (EPU, 2021).

While Penang has the highest value created per employee across the leading states in high-tech manufacturing such as Selangor, Johor, and Kedah (Penang Institute, 2019), it is competing with other attractive investments destinations in the region such as Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia. These countries are relatively cheaper and are becoming the more preferred destination for manufacturing industries (Woo, 2020).

Another challenge for Penang is to ensure that growth is inclusive. While income growth is positive, cost of living is becoming a serious issue. Housing in Penang is quite unaffordable, in particular for the lower- and middle-income groups. Housing is considered ‘affordable’ when the house price has a ‘median multiple’ (median house prices as a multiple of median annual household income) of around three times (3.0x) the annual income. [3]

Penang’s median multiple in 2014 was at 5.2x, which is considered severely unaffordable (KRI, 2019). Home ownership rates in Penang have declined over the years, falling from 82 per cent in 2014 to 78.9 per cent in 2019 (DOSM, 2022-b). Part of the unaffordability is due to the inability of median incomes to keep up with the property prices.

Affordable housing in Penang is also challenging due to limited land space (Khoo, Malek, and Yasin, 2017). There are many constraints on Penang Island which leave very limited actual land use for development. For example, a significant part of the southwest district, especially the Balik Pulau area, are higher than 250 feet above sea level, and are thus strictly prohibited from any kinds of developments as outlined in the Penang State Structural Plan to preserve and control soil erosion (Kamarudin Ngah et al., 2015). Other constraints include the Water Enactment Act, which forbids development within a distance of 50 feet from the riverbank, irrigation areas, and forest reserve areas (representing 17.3 per cent of the island). Due to these limitations, development in the area undergoes heavy competition between property developers.

Approved development types also lean more towards building luxurious housing units and condominiums, which aims to attract high end buyers – both locals and foreigner, and not to serve the needs of the local communities.

While Penang has done well in the past few decades, with income per capita comparable to high income countries such as Portugal and Hungary, several challenges remain. Income distribution and poverty is increasing, quality and affordable healthcare is under pressure, and sustainable development is at risk. Penang attractiveness for investments is also under threat from upcoming alternative destinations in the region. Basic needs such as housing is becoming unaffordable to most locals. If left uncheck, the state comprehensive development agendas will only benefit a few and the positive growth enjoyed in the past few decades would be meaningless.

Footnotes

[1] The author is Distinguished Adjunct Researcher at Penang Institute and Research Fellow at the Institute of Malaysian and International Studies (IKMAS) of National University of Malaysia (UKM). Correspondence to Muhammed.abdulkhalid@ukm.edu.my, This paper draws heavily from the book “Timeless Penang: Tradition in Transition” to which the author contributed a chapter. [2] Dependency ratio is calculated by dividing number of dependents (aged 0 to 14 and above 65) with total population (aged16-64) [3] Median multiple is defined as median house prices as a multiple of median annual household income. Source: KRI, 2021.

References

Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM), 2022. Exchange Rates: Malaysian Ringgit (End of Period)Bernama, 2021. Tiara Sumberjaya, Koperasi Kampung Melayu Balik Pulau bakal bangunkan hartanah bernilai RM1.7 bilion.

Carnegie, Elaine R., Greig Inglis, Annie Taylor, Anna Bak-Klimek, and Ogochukwu Okoye, 2021. Is Population

Density Associated with Non-Communicable Disease in Western Developed Countries? A Systematic Review.

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 2638.

Chee, Su Yin, Abdul Ghapar Othman, Yee Kwang Sim, Amni Nabilah Mat Adam, Louise B. Firth. 2017. Land reclamation and artificial islands: Walking the tightrope between development and conservation. Global Ecology and Conservation, Volume 12, October 2017. Accessed in https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2017.08.005

Choong, Pui Yee, 2020. Innovations in Elderly Care Needed in Malaysia and in Penang. Penang Institute Monographs

#10. Accessed in https://penanginstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Innovations-in-Elderly-Care-Needed-in

-Malaysia -and-in-Penang.pdf

CIA, 2022. CIA World Factbook 2022.

DOSM, 2005. Social Statistics 2005/2004.

DOSM, 2016. Population Projections, 2010-2040.

DOSM, 2020-a. Household Income Survey and Basic Amenities Report, Malaysia.

DOSM, 2020-b. Vital Statistics, 2020.

DOSM, 2020-c. Household Income Survey and Basic Amenities Report, Penang.

DOSM, 2020-d. Household Expenditure Survey, Penang.

DOSM, 2021. Mid-Year Population Estimates 2021.

DOSM, 2021-b. Household Income and Poverty Incidence, 2020.

DOSM, 2022-a. Pulau Pinang. Accessed in https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/cone&menu_id=SEFo bmo1N212cXc5TFlLVTVxWUFXZz09

DOSM, 2022-b. Key Findings Population and Housing Census of Malaysia, 2020. State of Pulau Pinang.

DOSM, 2022-c. Key Findings. Population and Housing Census of Malaysia, 2020.

DOSM, 2022-d. Abridged Life Tables, 2019-2021.

DOSM, 2022-e. Consumer Price Index Malaysia June 2022.

DOSM, 2020-f. State Socioeconomic Report: Penang.

Economic Planning Unit (EPU), 2020. Shared Prosperity Vision 2030. Accessed in https://www.epu.gov.m y/sites/default/files/2020-02/Shared%20Prosperity%20Vision%202030.pdf

EPF, 2021. Internal data.

EPU. 2021. Twelfth Malaysia Plan, 2021-2025.

Habibullah, M. S., Sanusi, N. A., Abdullah, L., Kusairi, S., Hassan, A. A. G., & Ghazali, N. A. (2018). How Long

Does It Takes for a Poor State to Catch-Up to a Richer State in Malaysia? A Note. International Journal of Business

and Society, 19(2), 269-280.

Hussain, R, 2021. Development And Conservation of Waqf Asset: Waqf Pulau Pinang Experience.

IKU, 2016. National Health and Morbidity Survey 2016. Institute of Public Health.

IKU, 2020. National Health and Morbidity Survey 2019. Institute of Public Health.

Ismail, S., Bakar, M. A., Ismail, C. Z., & Ramli, N. A. (2021). Issues and challenges in wakaf seetee aishah property

development, Penang state Islamic religious council (MAINPP). Linguistics and Culture Review, 5(S3), 1111-1123.

JKN Penang, 2021. Laporan Tahunan 2020. Accessed in https://jknpenang.moh.gov.my/jknpunya/Laporantahunan2020/ Laporan%20Tahunan%20Jabatan%20Kesihatan.pdf

Kamarudin Ngah, Mohd Fitri Abdul Rahman, Zainal Md. Zan, Zaherawati Zakaria, 2015. Development Pressure in South West District of Penang: Issues and Implications. Procedia: Social and Behavioural Sciences. Volume 211, November 2015. Accessed in https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S187704281 5053963

Khoo, Suet Leng and Kuan Heong Woo, 2020. Making sense of place-making in Penang island’s affordable housing schemes: voices from key stakeholders. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, Volume 12, 2020 – Issue 3. Accessed in https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/19463138.2020.172 8690

Khoo, Suet Leng, Nor Malina Malek, Suziana Mat Yasin, 2017. Housing affordability woes and the state of developed underdevelopment in Penang. Malaysian Management Journal (MMJ) Vol. 21, December 2017. Accessed in https://e-journal.uum.edu.my/index.php/mmj/article/view/mmj.21. 2017.9046

KRI, 2019. Making Housing Affordable. Accessed in h t t p : / / w w w . k r i n s t i t u t e . o r g / a s s e t s / c o n t e n t M S / i m g / t e m p l a t e / e d i t o r / _FINAL_Full_Draft__KRI__Making_Housing_Affordable__with_hyperlink__220815%20(1).pdf

KRI, 2021. Median Multiple Affordability: Use and considerations. Accessed in http://www.krinstitute.org/asse ts/contentMS/img/template/editor/Views%20-%20Median%20Multiple.pdf

Ministry of Finance, 2021. Economic Outlook 2021. Accessed in https://belanjawan2021.treasury.gov.my/index.php/en/te-2021

MOH Penang, 2020. Ministry of Health Penang Annual Report, 2020.

Mohammed, Khalid Sabbar, Narimah Samat, and Yasin Abdalla Eltayeb Elhadary, 2014. Bottom up Approach:

Urbanization in the Perception of the Local Communities of Balik Pulau, Penang Island, Malaysia. British Journal of

Applied Science & Technology 4(32): 4533-4549, 2014.

Nambiar, Predeep, 2022. After 2 decades, Penang flood mitigation project to kick off in June. Accessed in

https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2022/01/04/after-2-decades-penang-flood-mitigation-project-to-kick-off-in-june/

National Higher Education Research Institute, 2010. The State of Penang, Malaysia: Self-Evaluation Report”, OECD Reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development, IMHE. Accessed in

https://www.oecd.org/countries/malaysia/45496343.pdf

Osman, Sazali, Lingfang Chen, Abdul Hafiz Mohammad, Lixue Xing, Yangbo Chen, 2021. Flood modelling of Sungai Pinang Watershed under the impact of urbanisation. Tropical Cyclone Research and Review, Volume 10, Issue 2, June 2021. Accessed in https://www.sciencedirect.c om/science/article/pii/S222560322100014X Penang Institute, 2020.

REFSA, 2020. Rethinking Malaysia’s Income Reclassification: Not B40, but B20. REFSA Brief, Issue 2, March 2020. Accessed in https://refsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Final_Income-Reclassification _B20.pdf

Richards, Daniel R., Paul Passy, and Rachel R. Y. Oh, 2017. Impacts of population density and wealth on the quantity and structure of urban green space in tropical Southeast Asia. Landscape and Urban Planning, Volume 157, January 2017. Accessed in https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/a rticle/abs/pii/S0169204616301839

Romanova, Elena, 2018. Increase in Population Density and Aggravation of Social and Psychological Problems in Areas with High-Rise Construction. Accessed in https://www.e3s-conferences.org/articles/e3sconf/abs /2018/08/e3sconf_hrc2018_03061/e3sconf_hrc2018_03061.html

Sanchez-Paramo, Carolina, Ruth Hill, Daniel Gerszon Mahler, Ambar Narayan and Nishant Yonzan, 2021. COVID-19 leaves a legacy of rising poverty and widening inequality. Accessed in https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/covid-19-leaves-legacy-rising-poverty-and-widening-inequality

Penang Green Council, 2022. Accessed in https://pgc.com.my/2020/penang-green-agenda/

Penang Institute, 2020-a. Penang Agricultural Policy Report. Accessed in https://penangi nstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Penang-Agricultural-Policy-report-final.pdf

Penang Institute, 2021. Penang Economic and Development Report 2019/2020. Accessed in https://penanginstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Penang-Economic-and-Development-Report-2019-2020.pdf

Peng, Yixiao and Hejie Zhang, 2022. Global Sustainable Development Evaluation Methods with Multiple-Dimensional: Sustainable Development Index. Accessed in https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2022.957095/full

The Edge Markets, 2020. Putrajaya pulls back govt guarantee for Penang’s US$500m loan to finance LRT project. Accessed in https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/putrajaya-pulls-back-govt-guarantee-penangs-us500m-loan-finance-lrt-project

UN, n.d. Definition of Dependency Ratio. Accessed in https://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/natlinfo/indicators/methodology_sheets/demographics/dependency_ratio.pdf

UNDP, 2022. Human Development Index (HDI). Accessed in https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human-development-index#/indicies/HDI

Woo, Sze Zeng Joshua, 2020. Sustainability Strategies based on Penang Infrastructure Corporation’s Projects.

Accessed in https://penanginstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Sustainable-Strategies-based-on-Penang-Infrastructure-Corporations-Projects.pdf

World Bank, 2020. A Silver Lining: Productive and Inclusive Aging for Malaysia. Accessed in https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/malaysia/publication/a-silver-lining-productive-and-inclusive-aging-for-malaysia

World Bank, 2021. World Development Indicator (WDI). GDP per capita, PPP (current international $), 2021.

World Bank, 2022-a. Country Classification. Accessed in https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

World Bank, 2022-b. Population density (people per sq. km of land area). Accessed in https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.POP.DNST

Yeap, Cindy, 2022. The bad and ugly side of allowing more EPF Account 1 withdrawals. Accessed in https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/bad-and-ugly-side-allowing-more-epf-account-1-withdrawals

You might also like:

![Malaysia’s Northern States: Improving Competitive Advantages and Industrial Growth]()

Malaysia’s Northern States: Improving Competitive Advantages and Industrial Growth

![ESG Disclosures among Public-listed Companies Based in Penang]()

ESG Disclosures among Public-listed Companies Based in Penang

![An Alternative Model of Skim Peduli Sihat to Pool Risks for B40 Households]()

An Alternative Model of Skim Peduli Sihat to Pool Risks for B40 Households

![Eradicating Child Marriages in Southeast Asia: Protecting Children, Challenging Cultural Exceptional...]()

Eradicating Child Marriages in Southeast Asia: Protecting Children, Challenging Cultural Exceptional...

![Deconstructing Trump’s Tariffs: The Impact on Penang’s Trade and Economic Resilience]()

Deconstructing Trump’s Tariffs: The Impact on Penang’s Trade and Economic Resilience