EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Countries in Southeast Asia have demonstrated that measures such as shuttering of borders, restrictions in movements and targeted testing are effective in abating the spread of Covid-19.

- At the same time, the experience in Philippines and Indonesia also show that downplaying the threat of Covid-19 and having incoherent directives in the implementation of lockdown can prove disastrous in times of pandemic.

- At the regional level, ASEAN does have various mechanisms for containing Covid-19. However, there is much room for improvement in how they are put to use.

- As the threat of new waves of Covid-19 looms, communities such as migrant workers, refugees and the hardcore poor who live in crowded areas are most vulnerable.

INTRODUCTION

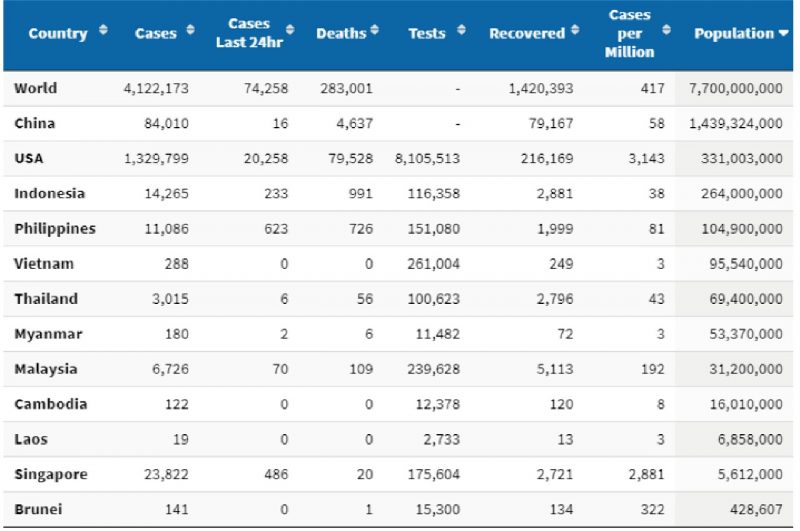

To date, while Vietnam, Malaysia and Thailand have shown relative success in containing the novel coronavirus spreading Covid-19, Indonesia and Philippines present the worst models of response.

This article discusses how member states of ASEAN have managed the pandemic outbreak so far, and also argues that refugees, the hardcore poor and those who live in crowded spaces will be most susceptible to eventual new waves of Covid-19.

Source : Center for Strategic and International Studies

THAILAND AND MALAYSIA

Thailand began to implement a partial lockdown in March as the cases of Covid-19 rose. The Thai government closed its borders, banned social gatherings and restricted domestic travel. Only essential services were allowed to continued.[1] These stricter measures were catalysed by one of the biggest clusters in Thailand – the Lumpinee Boxing stadium cluster to which one out of 53 cases were related.[2]

The Thai government also prohibited the annual Songkran Festival in April to prevent people from gathering in crowds. All these measures effectively prevented people from gathering in groups, and subsequently helped to lower the rate of infection.

Besides that, Thailand’s robust healthcare system has been critical in the fight against Covid-19. In 2019, the US magazine CEO World ranked Thailand 6th in its list of countries with the best healthcare system.[3] The ranking measures the infrastructure, the competence of the health care professionals, quality of medicine and government’s readiness. For instance, as early as February, doctors in Thailand have been using a combination of HIV drugs and flu drugs to treat Covid-19 patients.[4]

Although not a vaccine, this cocktail of drugs helps some patients to recover faster. The higher discharge rate of recovered patients has also ensured that their healthcare system continues to have sufficient capacity to handle new cases. Thailand’s medical cautiousness extends to nurses making baby face shields to protect new-born babies in the hospitals. The country’s investment in the health sector has definitely pay off, now when the country needs to contain the spread of Covid-19.

Likewise, Malaysia’s healthcare system is also reasonably well-equipped to face this time of crisis. In the same ranking done by CEO World, Malaysia ranked 34th out of 89 countries evaluated.[5] In addition, private hospitals, universities laboratories and retired healthcare professionals have been mobilized to increase the capacity to contain the pandemic. Malaysia was also decisive in imposing the Movement Control Order (MCO) from 18 March onwards. Beyond essential services, almost all economic activities were stopped. Malaysia also shuttered its borders to stop imported cases, and banned interstate travelling.

Enhanced Movement Control Order (EMCO), a stricter version of MCO was also implemented in places with a high infectivity rate. The Health Ministry also followed South Korea in focusing on testing. But instead of random mass testing, Malaysia opted for targeted testing among those most susceptible to Covid-19, such as those who have been in close contact with a patient. The combination of all these strategies definitely helped Malaysia to flatten the curve. The current Conditional Movement Control Order (CMCO) which allows a majority of economic activities to operate with stringent SOPs also helps to acclimatize Malaysians to adapt to living with the new normal.

The experience in Malaysia and Thailand shows that measures such as the closing of borders, restrictions on domestic travelling, social distancing and a robust healthcare system help in abating the spread of the virus. Consistent directives are also critical, especially in times of crisis. Nevertheless, neither Malaysia nor Thailand are out of the woods yet as long as no vaccine has been developed.

At the time of writing, several clusters in Malaysia have reported an increase in cases.

PHILIPPINES AND INDONESIA

By contrast, Philippines and Indonesia presently offer the poorest models of responses in the region. In the Philippines, President Duterte initially mocked social distancing measures. He soon changed his mind, however, and stated that Covid-19 would rampage the country and he professed that he was desperate.[6] He then announced a month-long lockdown of Metro Manila and the island of Luzon. A series of unclear announcements followed on how the quarantine would be implemented.[7]

On 11 May, he extended the lockdown for Manila to 11 weeks.[8] Although this may be a necessary measure to save lives, the hard-core poor are most affected and face the double whammy of food security and the risk of infection.

Indonesia, on the other hand chose to prioritize the economy and downplayed the severity of Covid-19. Until early March, the Indonesia government denied that there were cases in Indonesia, arguing that the virus cannot survive in humid weather.[9] By mid-March, President Jokowi finally admitted that he was withholding information on Covid-19 to prevent public panic.[10] Subsequently, the government began to implement a partial lockdown in several cities and towns, and introduced social distancing rules to contain the pandemic.

President Jokowi also banned the annual exodus of people from the urban areas at the end of the month of Ramadhan, known as mudik.[11] But this came too late; cases had already begun to surge. In addition, Indonesia struggled with a shortage in testing kits, personal protective equipment (PPE), ventilators and manpower. Although the government does release official numbers of infection and death tolls, it is widely believed that these figures do not represent the actual cases of infection and mortality rate.

The Philippines and Indonesia show that weaknesses in crisis communication, incoherent directives, and the unwillingness to acknowledge the severity of the pandemic are a recipe for disaster in times of pandemic. In balancing between concerns over public health and the stability of the economy, leaders have tended to downplay the advice of health experts in meeting the crisis.

CAMBODIA AND MYANMAR

Cambodia was cautious from the start, taking a targeted approach by testing migrant workers returning from South Korea, Thailand and Malaysia[12]. The government also cancelled the annual Khmer New Year holidays, educated the public on the symptoms of Covid-19 and imposed travel bans. Effective contract tracing and self-discipline of the community also helped in containing the virus. The low infectivity rate in Cambodia testifies to the success of these measures.

In Myanmar, national and regional governments rolled out stringent social distancing measures, and partial lockdowns. The country’s Ministry of Health and Sports (MOHS) also focused on contract tracing. Contributions from volunteer organizations and private healthcare sector also boosted overall capacity.[13] However, socio-political conditions are such that Myanmar remains vulnerable, especially among displaced minorities staying in overcrowded camps.[14]

Cambodia, Myanmar and Laos have also relied on China’s assistance in the battle against Covid-19. A team of Chinese medical experts arrived in Laos five days after Laos confirmed two cases of Covid-19. The team provided PCR test kits, KN95 masks and training support.[15] Similarly, a Chinese medical team from Guangxi province delivered medical supplies such as masks, ventilators and test kits to Phnom Penh. In Myanmar, besides medical supplies, a Chinese medical team from Yunnan arrived in Yangon for a 14-day visit on April 8 and another visit on April 24.[16]

Apart from the prompt medical assistance from China being of help for the mainland Southeast Asian countries, the high compliance rate of the people has been a redeeming factor in stopping the spread of the disease.

SINGAPORE AND VIETNAM

Singapore and Vietnam responses are shaped by their experiences with SARS in 2003. Both countries immediately adopted a proactive approach. From the onset of the Covid-19 outbreak in Wuhan, Vietnam began to monitored its borders and issued prevention guidelines. It has also been extremely strict in its contract-tracing process and in monitoring confirmed and suspected cases.[17] The military and retired medical professionals were also mobilised to fight the pandemic. This heightened sensitivity of the government and the cooperation of the community helped Vietnam dodge an exponential spike in cases. Vietnam can be considered as an exemplary case in its approach to the crisis.

Similarly, Singapore was hailed as the ‘gold standard’ by Harvard University for case detection.[18]

Singapore did all the right things as early as in February putting into place country-imposed border controls, strict contact tracing of suspected cases, and a home-quarantine regime for suspected cases. Having a healthcare system of first-world standard has also been a big asset. Government officials also held regular press conferences to inform the public about latest developments. This presented a good model for crisis communication.

Despite taking these measures, however, Singapore was hit by a wave of infection, largely affecting migrant workers. As of 12 May, Singapore recorded more than 24,000 confirmed cases, a majority of which are migrant workers staying in crowded dormitories. The Singapore government finally implemented a partial lockdown or ‘circuit breaker’ that began on April 7.

The Singapore experience exhibits how a serious oversight by the authorities easily puts in jeopardy the whole struggle, however comprehensively thought out it may have been. It also highlights the fact that vulnerability of dormitories and other crowded places.

ASEAN’S RESPONSES

On 14 April, ASEAN made a special declaration to combat Covid-19 by strengthening public health cooperation, intensifying the provision of medical supplies and providing appropriate assistance to member states, among others.[19] To be sure, ASEAN boasts multifaceted mechanisms to face pandemics, such as the ASEAN Senior Officials Meeting on Health Development (SOMHD), ASEAN Plus Three Mechanism Responding to Covid-19, ASEAN Emergency Operations Center (EOC) Network for Public Health, ASEAN Plus Three Field Epidemiology Training Network, ASEAN Risk Assessment and Risk Communication Centre (ARARC) and the ASEAN Health Cluster 2 on Responding to All Hazards and Emerging Threats. Yet this array of bodies can also be ASEAN’s weakness in that too much committees can complicate information sharing.

ASEAN has also been criticized for its slow response to Covid-19, especially given its experience of SARS in 2003, but one has to acknowledge that the present disease presents a different set of challenges because of its high infectivity rate. It is also inevitable that ASEAN members states prioritizes national measures over regional ones.

Even so, there are some areas that the regional association could have coordinated better. A case in point are the hundreds of thousands of Malaysians who shuttle between Johor Bahru and Singapore on a daily basis. The sudden closing of borders by the Malaysia government on the 18th March left many Malaysians stranded in Singapore with some struggling to find appropriate accommodation. In this regard, closer coordination between the two countries would have been helpful.

When borders are closed, it is inevitable that there will be supply chain disruptions. As a regional body committed to further economic integration, ASEAN could have worked to keep certain regional trade routes open, and minimized the supply chain disruptions.

CONCLUSION

In the fight against Covid-19, Southeast Asia countries showed some effective responses such as closing down of borders, movement control, targeted testing and the mobilisation of a good healthcare system. Certainly, the compliance of the people has been equally important.

However, the experience in Indonesia and the Philippines also highlights the importance of crisis communication.

The threat of Covid-19 will continue as long as there is no vaccine available, and so, no government can afford to be complacent. In the near future, sporadic clusters of infections should be expected. Singapore is a case in point. Notwithstanding its proactive approach, the country could not dodge a spike of cases among migrant workers. In general, migrant workers, refugees and the hard-core poor, in staying in overcrowded spaces, face higher chances of infection. Social distancing is not an option for most of them.

In conclusion, governments should learn from this crisis that ignoring the vulnerable communities in their midst can undercut any other effective measure that has been implemented.

[1] Knight R.T. 2020,”Thailand to Impose Broad Lockdown to Fight Novel Coronavirus”, Bloomberg, viewed 9 May 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-25/thailand-to-impose-broad-lockdown-to-fight-spread-of-coronavirus

[2] Saiyasombut S. 2020, “Thailand orders probe into military-run boxing stadium after COVID-10 cluster found”, Channel News Asia, viewed 12 May 2020 https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/thailand-orders-probe-into-military-run-boxing-stadium-after-12584310

[3] “Thailand’s healthcare ranked sixth best in the world”, The Bangkok Post, viewed 8 May 2020 https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/1746289/thailands-healthcare-ranked-sixth-best-in-the-world

[4] “Coronavirus: Thailand Doctor use HIV and flu drugs for treatment”, Pharmaceutical Technology, viewed 8 May 2020 https://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/news/coronavirus-thailand-treatment-combo/

[5] Ireland, S. 2019. “Revealed: Countries with the best Heath Care Systems, 2019”, CEOWorld Magazine, viewed https://ceoworld.biz/2019/08/05/revealed-countries-with-the-best-health-care-systems-2019/

[6] Heydarian R.J. 2020, “The Wrong Way to do a Lockdown in the Philippines”, AsiaTimes, viewed 9 May 2020 https://asiatimes.com/2020/04/the-wrong-way-to-do-a-lockdown-in-the-philippines/

[7] Searight A. 2020, “ Strengths and Vulnerabilities in Southeast Asia’s Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic”, Center for Strategic and International Studies viewed 9 May 2020 https://www.csis.org/analysis/strengths-and-vulnerabilities-southeast-asias-response-covid-19-pandemic

[8] “Philippine president to extend COVID-19 lockdown beyond nine weeks,” ChannelNewsAsia, viewed 12 May 2020 https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/covid-19-the-philippines-extend-lockdown-nine-weeks-12723760

[9] “Saat Luhut Bicara Corona Tak Tahan Cuaca Panas Indonesia”, DetikNews, viewed 9 May 2020 https://news.detik.com/berita/d-4963524/saat-luhut-bicara-corona-tak-tahan-cuaca-panas-indonesia

[10] Pangestika D. 2020, “’We don’t want people to panic’: Jokowi says on lack of transparency about Covid 19 cases, The Jakarta Post

[11] Tambun T and et al. 2020, “Jokowi bans Mudik as Police prepare to close off roads in and out of Jakarta”, Jakarta Globe, viewed 9 May 2020. https://jakartaglobe.id/news/jokowi-bans-mudik-as-police-prepare-to-close-off-roads-in-and- out-of-jakarta/

[12] Meta K. 2020, “Cambodia Rural Clinics Adopt Travel-base Covid-19 Test Strategy”, Voice of America, viewed 9 May 2020 https://www.voanews.com/covid-19-pandemic/cambodia-rural-clinics-adopt-travel-based-covid-19-test-strategy

[13] Kyaw S W. 2020. “Myanmar and Covid-19”, The Diplomat, viewed 9 May 2020 https://thediplomat.com/2020/05/myanmar-and-covid-19/

[14] Searight A. 2020, “ Strengths and Vulnerabilities in Southeast Asia’s Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, viewed 9 May 2020, https://www.csis.org/analysis/strengths-and-vulnerabilities-southeast-asias-response-covid-19-pandemic

[15] Makichuk, D. 2020. “China’s Medical Experts to the rescue in Laos”, Asia Times, viewed 9 May 2020 https://asiatimes.com/2020/04/chinas-medical-experts-to-the-rescue-in-laos/

[16] “Southeast Asia Covid-19 Tracker”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, viewed 9 May 2020 https://www.csis.org/programs/southeast-asia-program/southeast-asia-covid-19-tracker-0#Indonesia

[17] Nortajuddin N. 2020, “Vietnam’s Exemplary Response to Covid-19”, The ASEAN Post, viewed 9 May 2020 https://theaseanpost.com/article/vietnams-exemplary-response-covid-19

[18] “Harvard :Covid-19 case detection in Singapore is ‘gold standard’, The StarOnline, viewed 9 May 2020 https://www.thestar.com.my/news/2020/02/18/covid-19-detection-in-singapore-039gold-standard039-for-case-detection-h arvard-study

[19] “Declaration of the Special ASEAN Summit on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)”, ASEANSEC, viewed 10 May 2020 https://asean.org/storage/2020/04/FINAL-Declaration-of-the-Special-ASEAN-Summit-on-COVID-19.pdf

Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng, Editorial Team: Alexander Fernandez, William Tham and Nur Fitriah (designer)

You might also like:

![Urgent Need to Strengthen Malaysia’s Legal Framework Against AI-Driven Scams]()

Urgent Need to Strengthen Malaysia’s Legal Framework Against AI-Driven Scams

![[Rapporteur Notes] Penang Economic Summit 2022: The Post-Pandemic Economic Reset]()

[Rapporteur Notes] Penang Economic Summit 2022: The Post-Pandemic Economic Reset

![Investment Facilitation: A One-Stop Mechanism Needed to Assist Investors in Penang and Malaysia]()

Investment Facilitation: A One-Stop Mechanism Needed to Assist Investors in Penang and Malaysia

![Time for Malaysian States to Introduce “Non-Constituency Seats” (NCSs)]()

Time for Malaysian States to Introduce “Non-Constituency Seats” (NCSs)

![The Digital Free Trade Zone – A Path to Inclusive Growth?]()

The Digital Free Trade Zone – A Path to Inclusive Growth?

![[Rapporteur Notes] Penang Economic Summit 2022: The Post-Pandemic Economic Reset](https://penanginstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/thumbnail-1-150x150.jpg)