Executive Summary

- Budget 2019 offers a first real glimpse into the concrete plans that the Pakatan Harapan

(PH) government has for Malaysia during its first full calendar year in power - This report serves as an update to the long-run development expenditure (DE) analysis conducted by Penang Institute earlier this year, and highlights some of the more striking changes in DE between Budget 2019 and the budgets of the past decade

- The most critical feature of this budget relates to the drastic curtailment of DE allocations to the Prime Minister’s Department (PMD), with funding slashed by 70% relative to the average seen during Najib Razak’s second term as prime minister. Most of this RM8.5bil decrease in PMD funding comprises of budgetary items which have been either repealed, or transferred to other more appropriate ministries

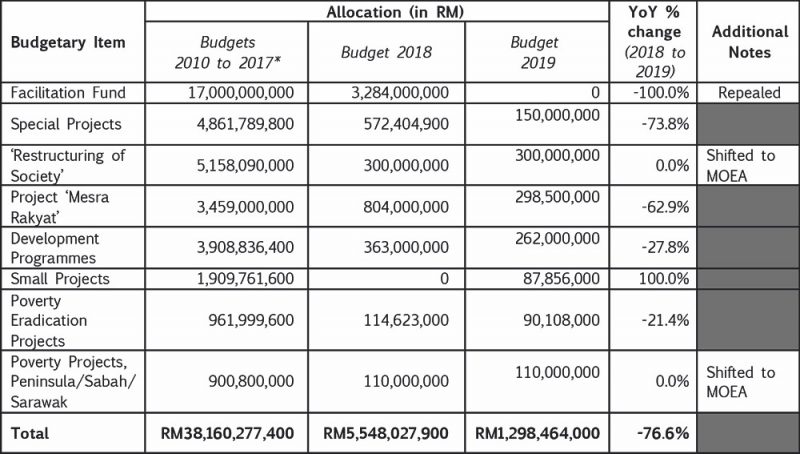

- Projects which formed Najib’s “slush fund” have seen their aggregate allocation curtailed by almost 77% relative to the previous budget, and account for RM1.3bil of DE in Budget 2019

- Despite these positive changes enacted by PH, much work remains to be done to ensure episodes akin to Najib’s misuse of DE funding do not occur again. Future Malaysian budgetary processes will need to take strong steps in the direction of transparency and accountability

Introduction

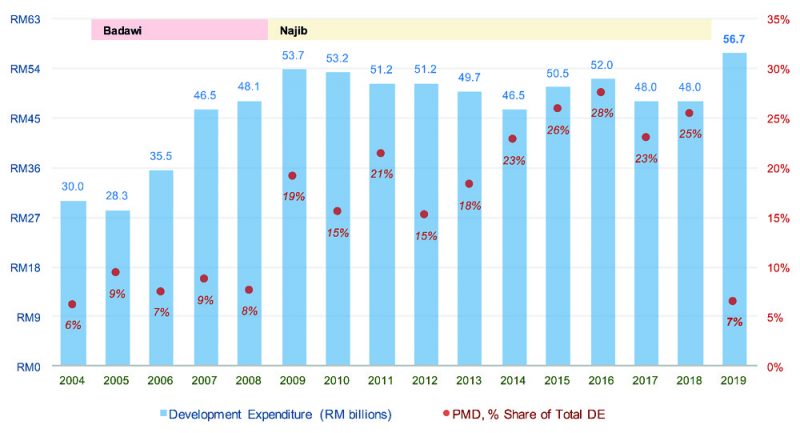

Budget 2019, tabled by Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng in Parliament on November 2, 2018, offers a first tangible glimpse of the concrete policy plans that the Pakatan Harapan (PH) government has for its first full calendar year in office. The allocation of RM56.7bil towards development expenditure (DE) equates to an RM8.7bil increase over its 2018 allocation and represents the highest absolute DE figure in federal budgets since Merdeka.

Importantly, it breaks two worrying trends seen under the Najib Razak [1] administration between 2009 and 2018; first, of steadily declining DE allocations, and second, of an unparalleled concentration of DE within the Prime Minister’s Department (PMD). These features are depicted in Figure 1.

Prior to Najib’s tenure, the share of DE accruing to the PMD remained comfortably under a tenth. Such an arrangement indicates that the many ministerial portfolios in Malaysia are recipients of sufficient and well-balanced funding for the various developmental programmes and policies under their individual jurisdictions. Under Najib, however, many DE budgetary items that may have been better placed under the purview of the appropriate Ministries were instead parked under the PMD. As a consequence, the size of the PMD bloated [2].

A prominent example of this is the Pan Borneo Highway (PBH), which is in every sense a public works project that should fall under the domain of the Ministry of Public Works (MOPW). Instead, RM4.3bil was allocated to the PMD for this project between 2016 and 2018.

This consolidation of power and money within the executive branch of government is dangerous as it closes the window to transparency and sound governance, and opens the door to the possibility of corruption, cronyism, and the mismanagement of funds. The case of the PBH succinctly exemplifies some of these dangers: the lucrative Project Delivery Partner (PDP) role for the Sarawak portion of the highway was in 2015 given to a little-known company controlled by Bustari Yusof [3] – brother of then Minister of Public Works Fadillah Yusof.

Figure 1: Total DE and PMD share of DE, 2004 to 2019 [4]

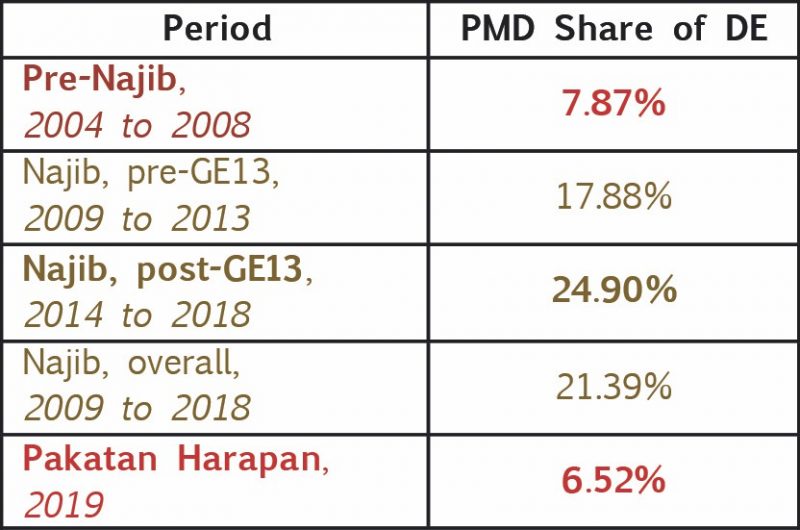

Budget 2019 marks a convincing step away from this unhealthy trend; for instance, RM2bil in DE funding for the PBH next year has been allocated to the MOPW rather than the PMD. This is just one budgetary item in a list of 23 that have been shifted away from the PMD towards more appropriate Ministries by the Ministry of Finance (MOF). This, combined with the repeal of five other PMD projects which were allocated RM3.33bil in DE in Budget 2018, is a significant contributing factor to the striking reduction in the share of DE accruing to the PMD in the latest budget. Table 1 highlights this change; the PMD share of DE peaked during Najib’s second term, between 2014 and 2018, at a staggering average of 24.9% – a stark contrast to the 7.9% average between 2004 and 2008, as well as the 6.5% as per Budget 2019. It would augur well for the country if future budgets follow in this vein, and steer clear of the concentration of discretionary spending power at the hands of the prime minister.

Table 1: PMD share of DE, 2004 to 2019

II Breaking Down DE in Budget 2019

An overview of Budget 2019 DE allocations is conducted below for the following ministries [5]:

- Prime Minister’s Department (PMD);

- Ministry of Defence (MOD);

- Ministry of Education (MOE);

- Ministry of Health (MOH);

- Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) [6];

- Ministry of Home Affairs (MOHA);

- Ministry of Public Works (MOPW);

- Ministry of Rural Development (MORD); and

- Ministry of Transportation (MOT).

These nine ministries have been singled out as they represent those which attained some of the highest DE allocations in past Malaysian budgets.

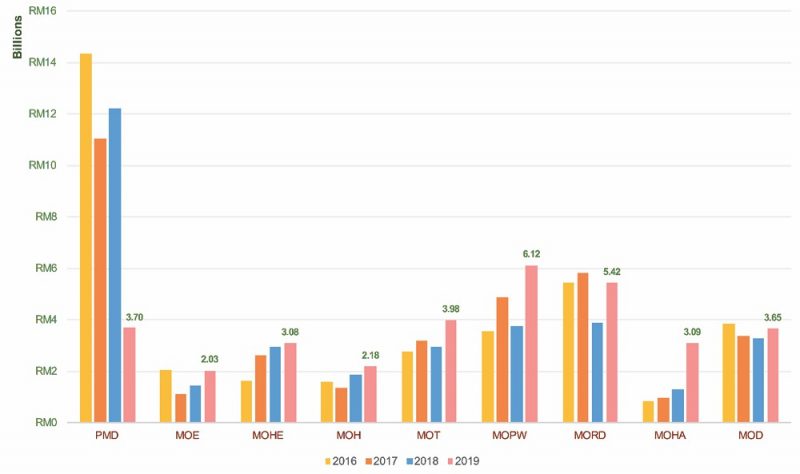

The breakdown of absolute DE for each of them between 2016 and 2019 is provided in Figure 2. Two prominent features are worth elaborating upon. The first of these pertains to the PMD allocation, which as mentioned in Section I reached unchartered heights under Najib. In a sense, normalcy has resumed with the latest budget; the spending power of the executive has been drastically curtailed and now lies comfortably within the range of the other ministries analysed in this study.

Figure 2: Breakdown of DE allocations by Ministry, 2016 to 2019

Secondly, DE allocations to the other ministries have increased and lie either at or close to their respective four-year peaks. These increases can be explained by three factors, the first two of which relate to corrections of the negative steps taken under Najib’s leadership. The first of these corrections involves the transferring of projects inexplicably placed under the PMD to more appropriate ministries. The case of PBH, mentioned in the previous section, is an example of this. The second factor contributing to the increase in ministerial DE allocations in Budget 2019 is the rectification of crowding-out issues which resulted from the concentration of DE within the PMD under Najib [7]. The remaining changes in the DE allocations to specific ministries can be explained by the need for development funding based on the policies and programmes planned by the PH government for 2019.

The fingerprints of the PMD have been ingrained on DE in Malaysia over the past decade. As such, it is imperative that the changes to the DE allocations to the PMD in Budget 2019 are highlighted, scrutinised and understood, including those which have been made to the group of policies and programmes that formed a significant component of Najib’s “slush fund”. These changes are the focus of the analysis conducted in Section III.

III Focusing on Changes to the PMD

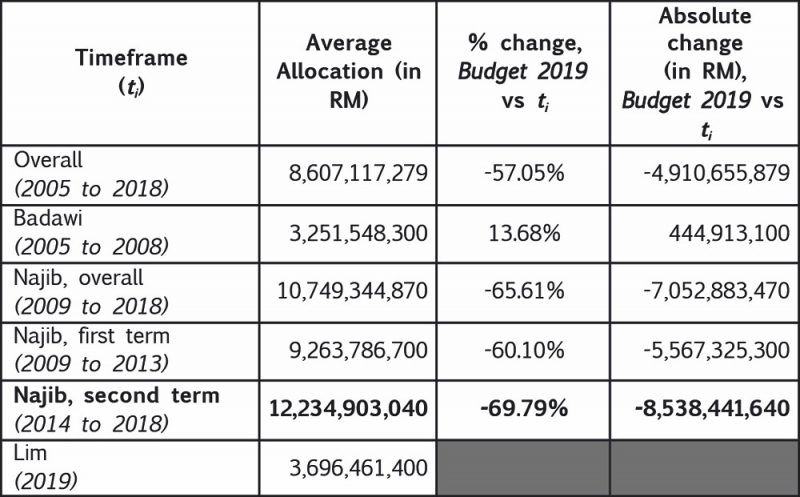

The influence of the PMD on DE in Malaysian budgets over the past decade has been stark, and the bloating of the PMD’s DE budget – for purposes both constructive and destructive – is testament to that. On a positive note, the PMD DE allocation has been slashed by almost 70% (or RM8.54bil) relative to the average seen during Najib’s second term between 2014 and 2018, from RM12.23bil to just under RM3.7bil for the upcoming year. A comparison between the Budget 2019

PMD DE allocation and those of grouped time periods dating back to 2005 is provided in Table 2.

Table 2: PMD DE allocations between 2005 and 2019

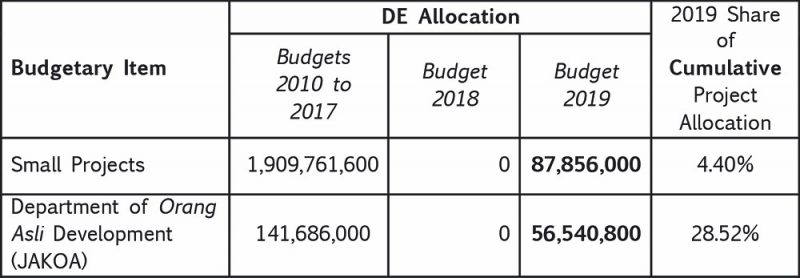

Before analysing the changes that have contributed to this RM8.5bil decrease in the DE spending capacity of the PMD, it is worth noting that two budgetary items not funded in Budget 2018 have been allocated DE funding for the upcoming year. These are listed in Table 3. The purpose of raising this point is based upon the allocation of RM87.86mil for Small Projects; this budgetary item formed a part of Najib’s “slush fund” between 2010 and 2017, when it amassed a total of RM1.91bil in DE allocations. Given the controversial history of this budgetary item, the MOF will do well to reveal details of these “projects” and address the intended purposes of their funds.

At the same time, it is encouraging to see an allocation of RM56.54mil towards the Department of Orang Asli Development, or JAKOA. Given that evidence of the misappropriation of funds, and of corruption and cronyism surrounding JAKOA has surfaced in the past [8], it is imperative that steps are taken to ensure that this 2019 DE allocation dedicatedly serves its stated intent, and assists in the fulfilment of Promise 38 of the PH manifesto – to advance the interests of the indigenous

peoples of Malaysia.

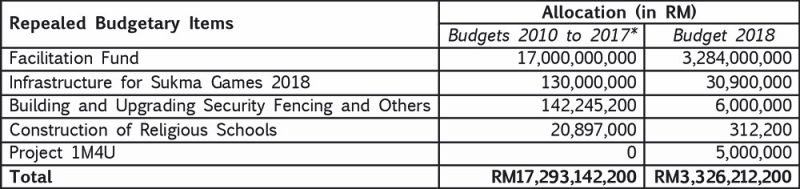

Table 3: Items unfunded in Budget 2018, but funded in Budget 2019

On the opposite end of the spectrum, five budgetary items under the purview of the PMD, which received a total of RM3.33bil worth of DE allocations in 2018, have been repealed in Budget 2019. These are listed in Table 4, which also reveals the total allocation accruing to these items between 2010 and 2017. Within the latter time period, these five “projects” have accrued cumulative funding of RM20.62bil, almost all of which had been dedicated to the Facilitation Fund, or Dana Fasilitasi – the largest single component of Najib’s “slush fund”. That this item has been scrapped entirely is positive news from the perspective of fiscal consolidation and anti-corruption. It is still not known what constructive purposes the Facilitation Fund served during Najib’s tenure, if any. Particularly given the magnitude of DE allotted to this budgetary item over the past decade, it would advance transparency and accountability that information pertaining to the use of these funds be revealed by the MOF.

Table 4: PMD budgetary items repealed in Budget 2019

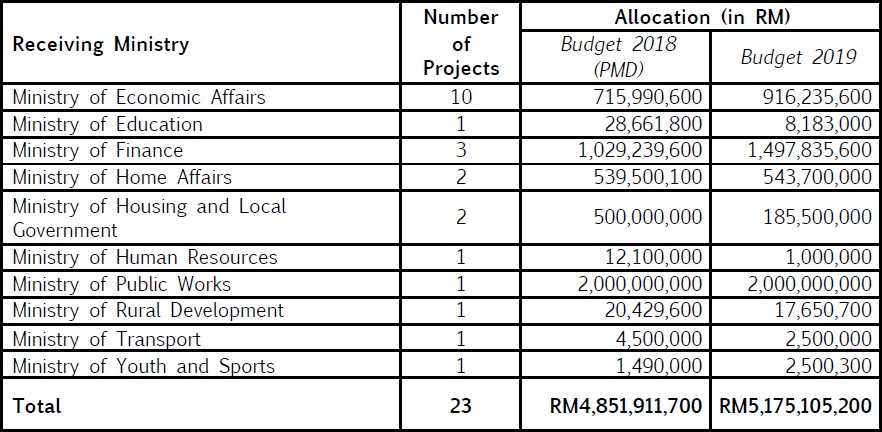

A further RM5.18bil worth of budgetary items, as per their respective Budget 2018 allocations, have been transferred from the PMD towards more appropriate ministries. This comprises of 23 separate DE items. This is an important step for two major reasons: first, a downsizing of the PMD is a necessity given its unnecessarily gargantuan growth over the past decade; second, it makes little sense for the PMD to be intimately involved in DE initiatives when other ministries exist specifically to take on tasks that lie within their domains of expertise. Again, the PBH illustrates this point perfectly: Why was the PMD allocated RM4.3bil in DE between 2016 and 2018 for the purpose of this project when it is clearly an item best left within the jurisdiction of the MOPW? A breakdown of the number of projects transferred to each ministry, these projects’ 2018 DE allocations to the PMD, and their Budget 2019 DE allocations is provided in Table 5.

Table 5: Overview of budgetary items transferred from the PMD

Table 6: Budgetary items transferred from PMD jurisdiction, 2018 to 2019

Table 6, meanwhile, reveals specifically the list of budgetary items that have been shifted away from the jurisdiction of the PMD, as well as the identities of the ministries to which each item has been transferred. Finally, the 2018 and 2019 budgetary allocations for each item are listed alongside their percentage change in funding across the two years. Scrutinising the list, it is reassuring to see that many of these items now sit on the portfolio of ministries best suited to lead each initiative; examples range from funding for the Economic Census being allotted to the Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA), to funding for New Village Development Programmes being allotted to the Ministry of Housing and Local Government.

Combining the formerly PMD-led DE initiatives which have been repealed or transferred to other ministries explains RM8.18bil of the reduction in the DE allocation of the PMD between Budgets

2018 and 2019. The remaining difference is derived from changes to the allocations of specific budgetary items still within the purview of the PMD, some of which have seen their allotments increase, and others yet which have seen theirs decrease.

IV What Happened to Najib’s “Slush Fund”?

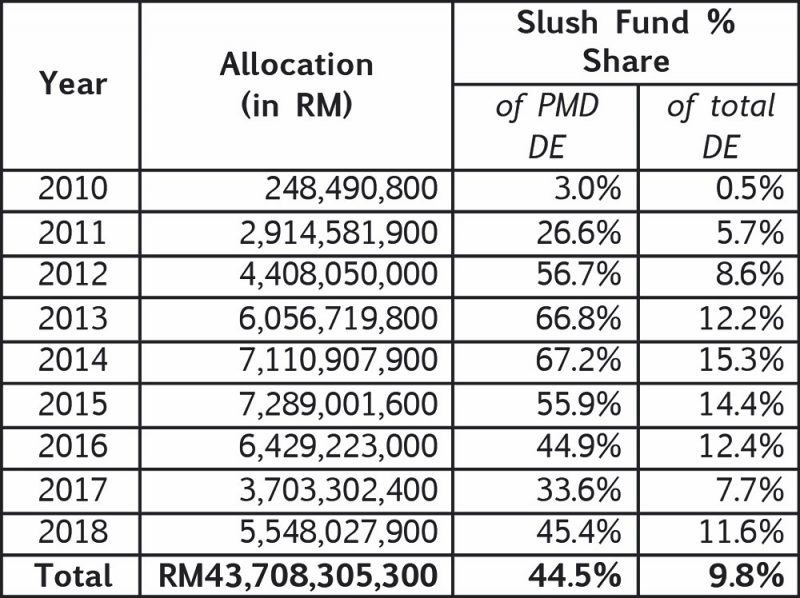

The existence of “slush fund” projects during Najib’s tenure as both prime minister and finance minister was first raised by the current Deputy Minister of Defence Liew Chin Tong [9], and contextualised in detail in a previous study on DE conducted by Penang Institute [10]. The defining common characteristic of these projects was a severe lack of transparency, with project details not made publicly available.

Table 7 highlights the magnitude of these misused funds; between 2012 and 2015, they accounted for between a half and two-thirds of PMD DE. In total, the “slush fund” projects accounted for RM43.71bil of DE from 2010 until Najib and BN’s unseating in May 2018. On average, these projects were responsible for 44.5% of PMD DE and just under a tenth of total DE between 2010 and 2018. These are funds that still need to be accounted for, regardless of the fact that they are now etched in Malaysia’s past.

What has happened with these “slush fund” projects since GE14, and more importantly, what does Budget 2019 do with them? The fates of two of these “slush fund” items, Small Projects and the Facilitation Fund, have been revealed in Section III. Before analysing the arrangements made for the rest of the component projects of Najib’s “slush fund”, it is important to preface the discussion by stating that the tainted nature of these projects can be altered if the issues that led to the negative scrutiny in the first place are addressed.

Table 7: Najib’s “slush fund” between 2010 and 2018

Introducing a significant degree of clarity and transparency to these budgetary items, and even rebranding them, would be steps in the appropriate direction. Most imperative, however, is

ensuring that these budgetary items accomplish whatever they purport to do.

Table 8: Najib’s slashed “slush fund”

Table 8 shows that seven of the eight “slush fund” projects are still in existence; the biggest, the Facilitation Fund, is the only one that has been halted entirely. Four others have seen their 2018 allocations slashed significantly, while two have maintained their allocations and been shifted to the MOEA. Only one – the aforementioned Small Projects – has seen an allocation increase. On the whole, these items have received just under RM1.3bil in funding for the forthcoming year, a 76.6% decrease relative to their Budget 2018 allocations.

V Ensuring Future Budget Transparency in Malaysia

A crucial step for Malaysia to take with regard to sound governance in DE moving forward is to ensure that episodes in history similar to Najib’s misuse of “slush funds” do not repeat themselves. Part of the solution to this is beyond the scope of this paper, in that it entails adhering to the principles of transparency, democracy, and accountability across all levels of government. Yet even with regard to annual budgets, there is scope for immediate improvement on the basis of these principles.

For instance, most citizens – outside those working directly for the MOF or the PMD – are unlikely to have any idea as to what the RM150mil allocation for Special Projects or the RM262mil allotment for Development Programmes truly entails. It is even more unclear if these items and the funding they receive indeed serve their purported purposes; between 2010 and 2018, RM1.08bil was allotted to the PMD for Poverty Eradication Projects, but there is a lack of evidence disproving the theory that these funds have been diverted or misappropriated. Given that public service should be rendered in service of the public, it should be the case that DE budgetary items – particularly those with vague project titles and large price tags – are elaborated upon in detail within, or separately to, the annual budgetary documents, especially when the revealing of such details does not compromise national security.

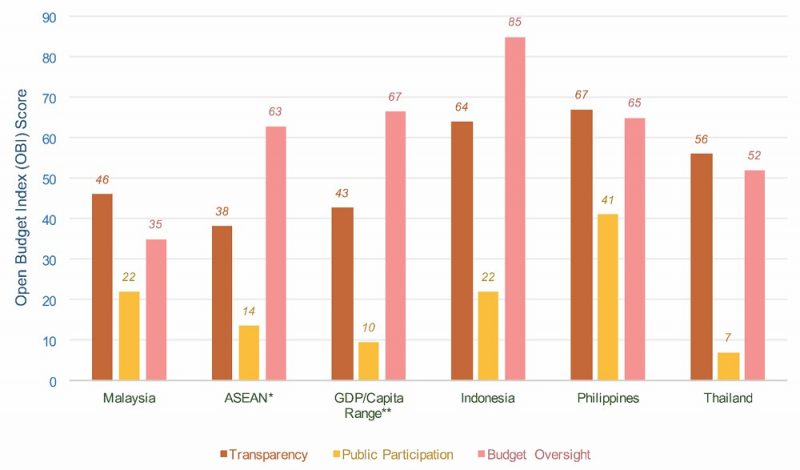

Figure 3 highlights Malaysia’s position among ASEAN counterparts [11], as well as nations with a GDP per capita within 10% of that of Malaysia [12], on three measures related to the “openness” of annual budgets. The data represented is drawn from the results of the Open Budget Survey 2017 conducted by the International Budget Partnership. The metrics upon which budgets are analysed comprise of budget transparency, public participation, as well as budgetary oversight. These key measures correlate strongly with the aforementioned principles of transparency, democracy, and accountability.

The scores Malaysia has achieved are not particularly encouraging. With regard to transparency, Malaysia trails its regional peers Indonesia, Philippines, and Thailand. It is clear that steps are to be taken to improve the transparency of Malaysian budgets moving forward; options include greater detailing of individual budgetary items, the regular publishing of accounts of actual expenditures, and the conduct of periodic revenue and expenditure reviews (such as mid- and end-year reviews). Insofar as budgetary oversight is concerned, strong improvement is necessary on this front; a severe lack of oversight and accountability aggrandises the possibility of the misappropriation and misuse of funds akin to Najib’s use of “slush funds”. Such a history should not be allowed to repeat itself.

Figure 3: “Open Budget Survey” scores for selected countries and regions

The PH government has made the elimination of corruption and the restoration of previously-threatened democratic values priorities for its current term in office. Given that annual budgets are arguably one of the most important and informative policy documents published by any government, these will need to be transparent, and to adhere to norms set by best international budgetary practices.

It is highly encouraging to see evidence of a convincing halt to the concentration of power and money under Najib’s PMD as far as DE is concerned, but the process does not end here. Further fiscal consolidation and the paring back of wasteful expenditure will be necessary over the coming years as Malaysia strives to improve its financial standing, while still addressing the contingent liabilities and off-balance sheet items from the Najib administration [13]. Beyond that, the MOF will have its work cut out in ensuring future Malaysian budgetary processes take necessary steps in the direction of transparency and accountability.

List of References

Central Intelligence Agency. 2018. “The World Factbook”. CIA: Washington, DC. Available at https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/index.html

International Budget Partnership. 2018. “Open Budget Survey 2017”. IBP: Washington, DC. Available at https://www.internationalbudget.org/wp-content/uploads/open-budget-survey-2017-report-en glish.pdf

Malaysia. Ministry of Finance. 2017. “Anggaran Perbelanjaan Persekutuan 2018”. Retrieved from http://www.treasury.gov.my/

Malaysia. Ministry of Finance. 2018. “Anggaran Perbelanjaan Persekutuan 2019”. Retrieved from http://www.treasury.gov.my/

Ong, Kian Ming; Joshi, Darshan. 2018. “Tracking Malaysia’s Development Expenditure in Federal Budgets from 2004 to 2018”. Penang Institute: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Available at https://www.penanginstitute.org/publications/issues/tracking-malaysias-development-expendi ture-in-federal-budgets-from-2004-to-2018/

[1] Najib was not only just the prime minister (PM), but the finance minister too. His use of this latter position to divert a substantial share of DE items and funding to his PMD has led to calls for future PMs to not concurrently assume the finance portfolio in the future.

[2] This “bloating” occurred on three fronts: i) the number of departments within the PMD; ii) the number of budgetary items under the purview of the PMD and the magnitude of their funding; and iii) the overall influence of the PMD and consequently, that of ex-PM Najib.

[3 ]https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2015/07/04/little-known-lbu-lands-lucrative-job-in-sarawak/

[4] This, and all figures and tables presented in this paper, are derived from statistics available on the Ministry of Finance website, http://www.treasury.gov.my/.

[5] The PMD is officially a department and not a Ministry, but the nomenclature is retained for the purpose of simplicity.

[6] The MOHE is officially considered a subset of the MOE under the current PH government, but to ease the comparison with past budgets, these ministries are treated separately for the purposes of this study.

[7] Ong and Joshi (2018) find that the cumulative increase in the “slush fund” allocation of DE between 2011 and 2018 is matched almost one-for-one by a cumulative decrease in the DE allocations of the MOE, MOH, and MOHE; this indicates that to a degree, DE allocations to the PMD “crowded out” DE funding that would have otherwise been allotted to MOE, MOH, and MOHE, among possibly other ministries.

[8] https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/opinion/2017/08/23/after-60-years-malaysias-forgotten-people-still-forgotten/

[9] https://www.malaymail.com/s/773989/slush-funds-in-budget-for-pms-department-deplorable-says-mp

[10] See Ong and Joshi (2018).

[11] ASEAN here includes Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. Singapore, Brunei and Laos are not participants to the Open Budget Survey and are excluded from the comparison.

[12] This list of countries includes Hungary, Kazakhstan, Poland, Portugal, Turkey, and Russia. GDP per capita figures have been drawn from the Central Intelligence Agency (2018).

[13] http://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/cover-story-debt-spiral–-whats-books-contingent-liabilities-and-offbalance-sheet-it ems

Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng, Editorial Team: Regina Hoo, Nur Fitriah, Ong Wooi Leng