Image source: eermakova

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY[*]

- This brief analyses the circumstances citizens of Penang venture into street food hawking and the prospects that this semi-tangible cultural heritage of Penang will be passed on to the next generation.

- On-site interviews were conducted with 15 street food hawkers on the reasons for their venturing into street food hawking, their business’s history, how they learned to prepare street food, and their willingness to pass down street food preparation knowledge.

- Most ventured into street food hawking either because it was part of the family business (three subjects) while some are founder-vendors of their stall (the remaining subjects). All of them view street food hawking as a feasible avenue for earning a regular income, food preparation being one of the skills they already possess or are interested to improve upon. They learnt to prepare street food through informal apprenticeships that involved observation and occasional hands-on guidance from family members or acquaintances.

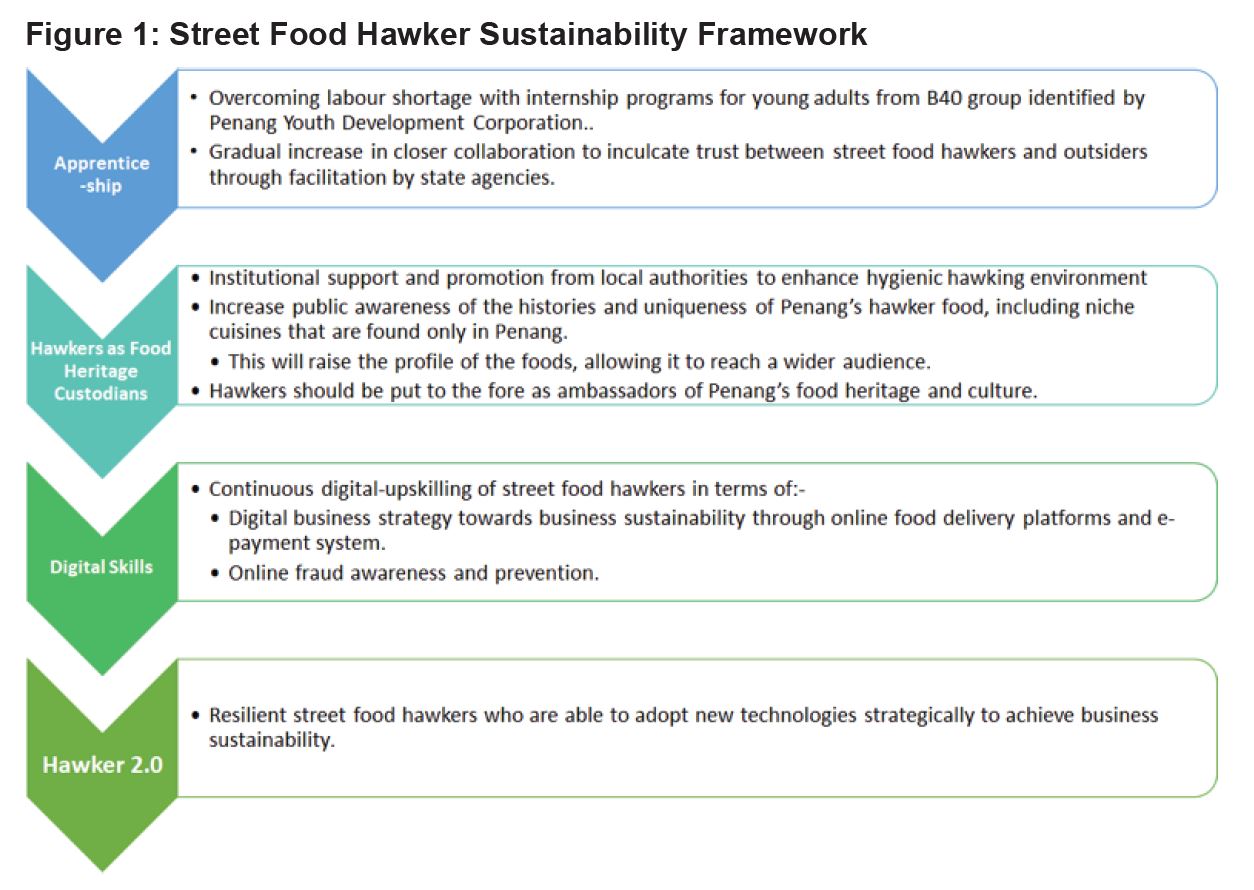

- This brief proposes a ‘Street Food Hawker Sustainability Framework’ that consists of three approaches: (1) Apprenticeships for B40 youths at street food hawker stalls, (2) Uplifting the reputation of street food through public awareness of the history and uniqueness of Penang street food, culminating with street food hawkers being appointed Food Heritage Custodians to raise the profile of Penang hawker food and to reach a wider audience, and (3) Refreshing and updating hawkers’ knowledge of digital tools and their usefulness to their microenterprise.

- The outcome of this sustainability framework, titled Hawker 2.0, will see street food hawkers function as guardians of a resilient Penang street food culture that is not only known far and wide, but that exhibits built-in digital-savviness and a pipeline to a future generation of hawkers.

BACKGROUND

Street food hawkers provide affordable ready-to-consume food to city dwellers (Azis & Tek, 2018; Bhowmik, 2005; Henderson, 2016). Sujatha et al. (1997) note that street food is an important source of energy for blue collar workers whose meal choices are limited by low mobility and little time. Street food vendors proliferate where a culture of ‘eating-out’ or ‘takeaway’ is prevalent (Bhowmik, 2005). These street foods are often a tourist attraction (Azis & Tek, 2018; Dawood, 2019; Francis, 2014; Henderson, 2016) and contribute to society’s identity (Tarulevicz, 2018).

Street food hawking is a source of income for the lower income group (i.e. the B40 – the bottom 40 percentile in income). It is a common alternative especially among womenfolk who do not have their own modes of transportation; these can easily set up a street food stall right in front of their homes, or near their homes (Franck, 2012). Being an informal sector source of income, street food hawking has been deemed as the “last resort” occupation for individuals who have been unsuccessful or unqualified in seeking and maintaining positions in the formal sector (Bhowmik, 2005; Todaro, 2015). In addition, street food hawking can often be viewed as a better alternative to being a lowly employee in the formal sector. At least one gets to retain control over one’s destiny while gaining a set of artisanal skills (Tarulevicz, 2018, Todaro, 2015).

This situation concerning economic and academic factors may be changing, however. Street food vendors from other demographical backgrounds are emerging in the wake of 21st-century recessions, as partially evidenced in Singapore (Bhowmik, 2005). There are also younger people taking over their ageing parents’ business with the intention of continuing their parents’ food taste and craft (Tarulevicz, 2018) or due to their old parents falling victim to the Covid-19 pandemic (Tanakasempipat, 2021).

In Penang, however, street food hawkers are usually old, and few youths are willing to take up the time-intensive and low-returns vocation (Lim & Liew, 2019). In fact, despite the above-mentioned trend, Singapore’s street food hawkers are of a higher median age, and even that, there is a tangible concern that there will be no successors to their business (Tarulevicz, 2018).

In research done on street food vendors in India, it was observed that street food hawkers tend not to have received any formal training and instead manage the street food trade through ‘learning-by-doing’. The learning usually comes through the street food vendor’s family (parents or other family members) or through informal apprenticeships in street food stalls or restaurants, or food production plants (Pilz et al., 2015).

Penang Institute, in collaboration with researchers from Multimedia University and UCSI University, carried out in-depth interviews with street food hawkers to analyse the circumstances under which individuals become involved in street food hawking, and to study future prospects of this semi-tangible cultural heritage of Penang. This project supplements a survey and case study on Penang street vendors done during the Covid-19 pandemic (see Yap et al., 2021). Specifically, the present report (1) discusses the mechanisms through which these hawkers learn their trade, (2) uncovers the circumstances and reasons the street food hawkers ply this trade, (3) evaluates the practicality of knowledge transfer of street food selling to the next generation, and (4) proposes a framework through which the semi-intangible street food culture can be sustained in the heritage city of George Town.

METHODOLOGY

The researchers visited street food hawker sites such as coffee shops, food court and individual stalls to seek permission for on-site interviews. These interviews were conducted during the business lull between lunch and tea time and sometimes after the end-of-day clean-up. The 15 street food hawkers who were interviewed were from the main ethnic groups (Malay, Chinese and Indian), who were selling a variety of street foods throughout the second quarter of 2022 in the North-East District of Penang. The interviews were conducted in English and Bahasa Melayu, and in the Penang Hokkien Dialect.

The street food hawkers were first asked demographic questions, followed by queries on their reasons for venturing into street food hawking, on their business’s history, their acquiring of knowledge on peddling street food, and whether they were willing to pass down that knowledge to others.

FINDINGS

Sample Description

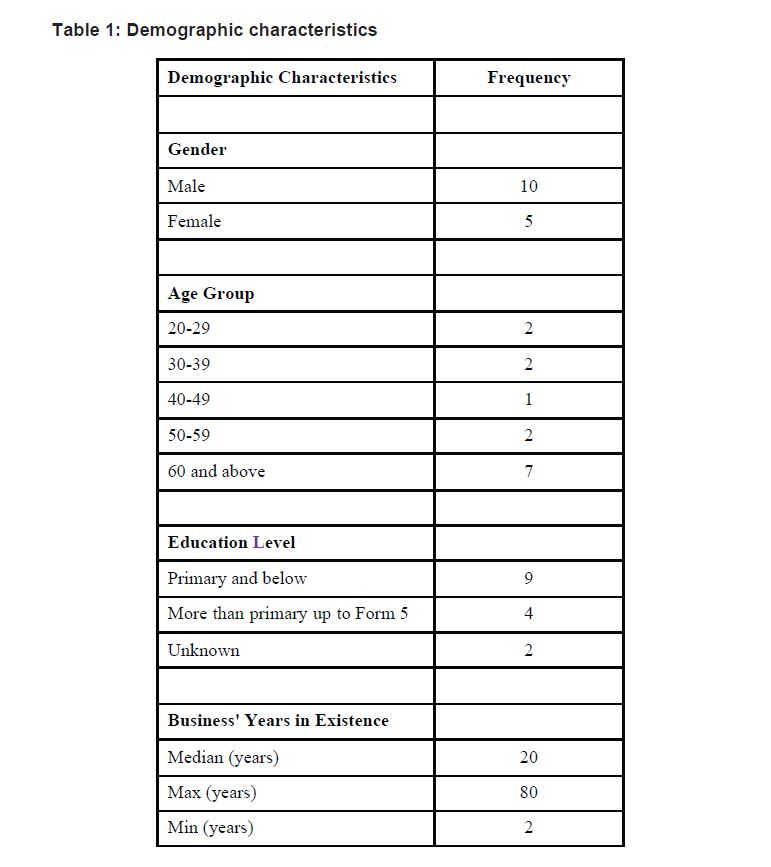

The demographics of the interviewees are found in Table 1 below. One interviewee did not reveal her age while two others did not reveal their education level. A majority of the interviewees are male, 50 years of age or older, and have low education. Three of the four interviewees who had more than primary school education are below the age of 40. In terms of the street food stall itself, the business’s length of existence ranged from two to 80 years. Furthermore, 11 interviewees were working in street food stalls that had been in existence for more than 20 years.

How Street Food Hawkers Get Their Start

Among the findings was that three interviewees got into their family’s street food business as second- (two cases) and third-generation (one case) street food hawkers. Interestingly, one interviewee started business during the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown while another was a regular job-seeker being groomed to take over the day-to-day management of the street food shop.

Thus, while three interviewees ventured into their family’s street food business, the remaining interviewees (twelve) were founder-vendors. This latter group started their business in order to earn a regular income, and food preparation was one of the skills they either possessed or were interested to learn further. Two female interviewees started street food hawking after being a stay-at-home mother and child minder respectively. Congruent with academic literature, loss of formal sector jobs was also provided as a reason for going into the street food business. One went in after retirement.

Apart from the three-generational street food stalls, the other interviewees were first-generation and sole proprietors, and 13 of the interviewees learnt street food preparation skills through informal apprenticeships with family members or acquaintances. This apprenticeship involved observation and sometimes, hands-on guidance. However, the interviewees also mentioned that their ‘recipes’ had been evolving since their apprenticeship days. This seems to suggest that the dish served by a particular street food hawker would be unique to that street food stall alone.

Some reasons for the evolution of recipes were given in the interview with Subject 2, who mentioned that some ingredients such as dried chillies differed in spiciness depending on the harvesting season, or in local parlance, they ikut musim (season-dependent). He stated that in his stall, ingredients were measured and weighed, and the spiciness would depend on the ingredients’ condition for that day. Other interviewees adjusted their recipe according to the quality of the ingredients obtained for that day. Recipe innovations will be further discussed in the following section.

Prospects of Street Food Continuity in George Town

All but three of the interviewees did not intend to pass down their skills to the next generation. In any case, they would not teach recipes to family members outright, but instead would consider the personality of the potential ‘student-relative’. For example, Subject 1 mentioned that her husband did not teach her stepson the recipe, as the young man was not mature and had owed illegal moneylenders money. If the recipe was passed to that young man, he may use that recipe as collateral for loans, and the illegal money lenders may open other stalls using that recipe, which would then dilute the reputation of the original stall.

A few hawkers mentioned that they had been offered substantial amounts of money for their recipes, but they had been unwilling to do so. The offers came from as far abroad as the United Kingdom, Australia and also Singapore. Subject 3’s concern is that, after ‘selling off’ the recipe, the fate of the recipe is uncertain, and may be sold off to yet another buyer. Subject 5’s worry, meanwhile, is similar to Subject 1’s – where the fear is that the person who obtained the recipe could negatively affect the stall’s good name.

Subject 1 was asked to provide daily supplies of the dish’s broth, which is its main selling ingredient, but the hawker was not willing, fearing that the buyer may dilute the broth “into two buckets from one” thus ruining the taste of the broth. In contrast, Subject 3 was willing to consider franchising – wherein he retains the recipe, prepares the main broth and the franchisee prepares the rest of the ingredients and sells to customers.

In contrast, Subject 2 was not willing to give up the recipe, since it was developed over the years by his father, and any interested parties should learn the business from scratch:

“Saya macam ini lah, nak berniaga, belajar sendiri, itu ja… Kalau ambil dari resipi orang dan buat macam berniaga di tempat lain, tak berbaloi, sebab hasil itu dari usaha kita. Itu pendirian saya lah”

However, Subject 6, who is young and is well-informed of the cult-like successes of local and foreign brands such as Maybank and Google, is more pragmatic, stating that “a good business must be carried on”, and that the ‘boss’ should ensure that the name of the stall is continued. Subject 6 stated that the stall proprietors should take the initiative to hire committed workers who are trustworthy and interested in learning the business, and not those who only wish to work the standard hours and do not have the passion to take the business to the next level. This interviewee has leveraged on social media to promote the street food business that he is in charge of. This has resulted in his customers not only consisting of Penangites, but also tourists from as far as away Johor and Kelantan.

The hawkers mainly learned from observing others, and based on the interviews, most developed their own recipe through trial and error. Subject 8 innovated on the stall’s recipe to accommodate changing tastes, ending up offering a vegetarian version. Subject 7 mentioned that it was not possible to pass on a street food recipe, saying that the apprentice’s street food output would depend on what the locals call ‘air tangan’ – the talent and imprint the individual had on the food’s taste. Subject 7 also mentioned that his father (the main cook) improvised on the original recipe and the food was now not similar to what it was at the outset. In contrast, Subject 5 worked hard to preserve the original recipe.

A majority of the street food vendors interviewed were above the age of 40. This does not bode well for Penang’s street food heritage. Those street food hawkers who were willing to pass their recipe down to future generation, would only do that for direct family members. The unwillingness of the hawkers to teach their own sons and daughters can be summed up in Subject 4’s response to this question: “Street food hawking involves a lot of hard work. The next generation should find an easier way to make money”.

Proposed Street Food Hawker Sustainability Framework

The proposed street food hawker sustainability framework below takes a leaf from Maglumtong and Fukushima (2022)’s evaluation of the Government Savings Bank of Thailand (GSB) Street Food Program (SFP). The three main components of the SFP are as follows:

- A loan programme

- An online payment support system

- Development of business knowledge

One observation made by Maglumtong and Fukushima (2022) was that loans applied for by street food hawkers were for small amounts, as the Thai hawkers were only looking to improve their current stalls and did not have designs to open a food truck or a restaurant. The online payment initiative faced challenges because not all hawkers had internet connection. Lastly, seminars to develop the Thai hawker’s business knowledge were not well-attended. Instead, a reality TV show on how a group of street food hawkers improved their street food business, was deemed by the hawkers to be more useful in that it offered inspiration, networking and knowledge (Maglumtong & Fukushima, 2022).

Based on the SFP, then, the ‘Street Food Hawker Sustainability Framework’ described in Figure 1 below proposes that the existing digitalisation initiative undertaken by Digital Penang be expanded with three additional initiatives:

1. Apprenticeship: State agencies should reach out to street food hawkers with potential apprenticeship opportunities in light of the labour shortage experienced by hawkers post-pandemic. Gradually, young adults from the B40 group can be screened to work with street food hawkers. A gradual approach is needed due to the fact that street food hawkers are wary of outsiders making their way into their business. It is proposed that the Penang Island City Council and Penang Youth Development Corporation collectively plan and execute this part of the framework.

2. Hawkers as Food Heritage Custodians: Tourism agencies need to increase public awareness of the history and uniqueness of Penang hawker food, including niche cuisines (apart from Penang staples such as nasi kandar and char koay teow). In addition, support and promotion from local authorities are required to enhance hygienic hawking environments. Street food hawkers could be appointed custodians of Penang’s food heritage, and their roles in promoting this semi-tangible cultural heritage should be in the forefront of tourism campaigns. These initiatives would raise the profile of Penang hawker food among a wider audience. This would help street food hawkers understand the purpose of sustaining their business for future generations, even as a younger generation gets attracted to this sector. This would widen the pool of future hawkers beyond the current batch who mostly ventured into street food hawking due to happenstance or as a job of last resort.

3. Digital Skills: Hawkers need to improve their digital skills. In addition, digital skills refresher courses are needed for hawkers to develop the confidence in using digital tools such as e-wallet and social media. Since Digital Penang was the agency that carried out the initial digital upskilling programme, this component should also be planned and executed by it. Apart from on-the-ground training, user-friendly digital platforms can be leveraged to upload simple videos on how fellow hawkers utilise digital platforms to take their business to the next level.

For list of references, kindly download the document to view.

Editor: Ooi Kee Beng

Editorial Team: Rahida Aini, Alexander Fernandez and Nur Fitriah (Designer)

[*]This publication resulted from research supported by the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS), Ministry of Education Malaysia (project number: FRGS/1/2019/WAB10/MMU/03/1). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the Ministry of Education Malaysia or the Malaysian Government.

Penang Institute provided support in data collection and reviewing of this brief through a Memorandum of Understanding with Multimedia University under the guidance of Ms Ong Wooi Leng, Fellow and Head of Socioeconomics and Statistics Programme.

Correspondence concerning this brief should be addressed to Dr Yvonne Lee, Faculty of Management, Multimedia University, Persiaran Multimedia, 63100 Cyberjaya, Selangor D.E. Email: yvonne.lelee@mmu.edu.my.

You might also like:

![Obesity in Malaysia: Unhealthy Eating is as Harmful as Smoking]()

Obesity in Malaysia: Unhealthy Eating is as Harmful as Smoking

![Reconnecting Accountability Chains to Reform State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs)]()

Reconnecting Accountability Chains to Reform State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs)

![Synergy among Stakeholders is Key to the Sustainability of Cultural Tourism in Penang]()

Synergy among Stakeholders is Key to the Sustainability of Cultural Tourism in Penang

![The ASEAN Treaty on Extradition: Best Understood within its Political-cultural Context]()

The ASEAN Treaty on Extradition: Best Understood within its Political-cultural Context

![Towards a Healthier Digital Childhood: Guidelines on Screen Use for Children]()

Towards a Healthier Digital Childhood: Guidelines on Screen Use for Children