EXECUTIVE SUMMARY[1]

- This brief discusses the trade relationship between the European Union (EU) and Malaysia amid the background of the high level of exports and imports between the two, and discusses some recent issues in this sphere.

- In terms of Compounded Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) in the 2010-2020 decade, EU’s exports to Malaysia was 0.6% whilst Malaysia’s exports to the EU recorded 5.1%. The CAGR (2010-2020) for total trade was 3.5%, reaching EUR35.3 billion in 2020.

- Negotiations between the EU and Malaysia were initiated early, but have since been put on hold. Meanwhile, EU-Singapore negotiations, which began in 2010 were completed in 2014 and the EU-Vietnam FTA was completed in 2015. Business groups are now lobbying for the resumption of EU-Malaysia FTA negotiations.

- Some recent issues imparting on Malaysia-EU trade ties are: palm oil trade related issues, stalled EU-Malaysia FTA talks, challenges in the broader ASEAN-EU region-wide FTA, and political issues in Malaysia.

- Malaysia is expected to continue being an important ASEAN member-state partner to the EU.

1. Introduction

Trade between Europe and Malay Peninsula dates back to the 16th century during the glory days of Melaka and the Straits of Melaka (Gunn, 2003), and today the Federation of Malaysia continue to enjoy good trade relationships with European Union (EU) member states and other countries in Europe. In fact, Malaysia is the EU’s 20th largest trade partner in the world and the third largest trade partner among ASEAN member states (AMS). Europe is a source of new investments and advanced technology for the Asian economies (Furuoka et al., 2017), and Malaysia as a trade-orientated, export-dependent economy has much to gain from this trend.

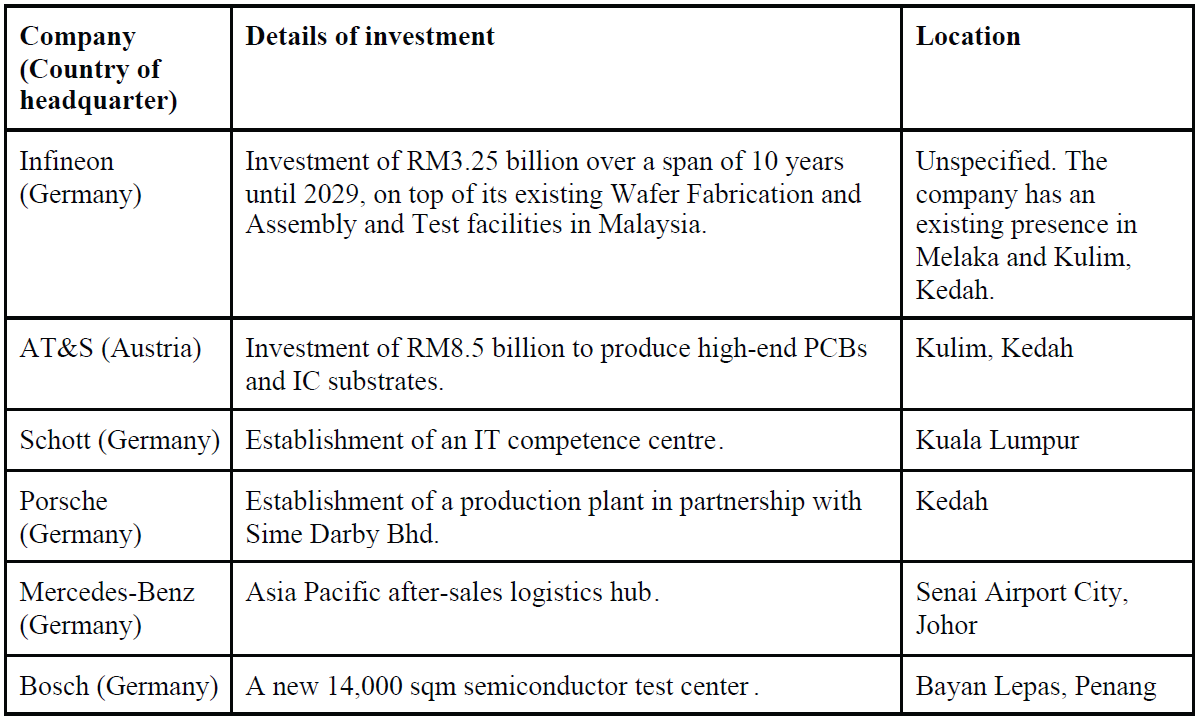

The healthy relationship between Malaysia and the EU is also evident in the continued inflow of foreign direct investments from multinational corporations from EU countries, even in the midst of challenges from the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021 (see Table 1).

Table 1: Public announcements of investments by EU-headquartered companies in Malaysia, 2020 and 2021

Source: Author’s compilation based on individual companies’ announcements

There have been efforts in the past to strengthen trade ties between EU and Malaysia, in particular in establishing a bilateral free trade agreement (FTA). However, negotiations were halted in 2012; a relaunch of talks in 2017 has not led to any advancements. Some of the related issues are discussed in sections 3 and 4.

This present brief discusses the trade relationship between the EU and Malaysia, amid the background of the high levels of exports and imports between Malaysia and the EU, and discusses some recent issues in this sphere.

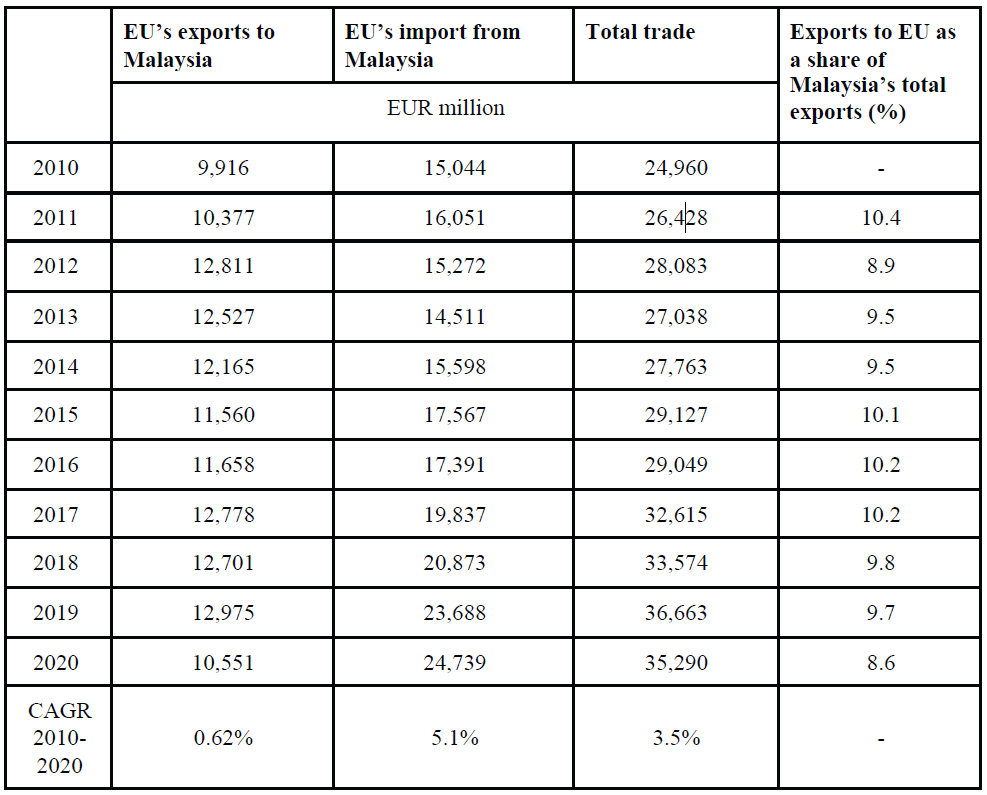

2. Trends in EU-Malaysia trade

Trade in goods

In 2020, the EU’s export of goods to Malaysia was valued at EUR10.6 billion, whilst EU’s import of goods from the EU was around 24.8 billion (Table 2). In terms of Compounded Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) in 2010-2020, EU’s exports to Malaysia was 0.6% whilst Malaysia’s exports to the EU 5.1%. The CAGR (2010-2020) for total trade of goods was 3.5%, reaching EUR35.3 billion in 2020.

Table 2: EU-Malaysia exports, imports and total trade in goods, 2010-2020

In terms of types of goods traded, Malaysia’s exports to the EU are mainly machinery and appliances, plastics, rubber and articles, animal or vegetable fats and oils, optical and photographic instruments, etc., and products of the chemical or allied industries. These constitute around 90.8% of total exports from Malaysia to the EU in 2020. Meanwhile, Malaysia imports machinery and appliances, products of the chemical or allied industries, transport equipment, optical and photographic instruments, etc. and base metals and articles thereof. These products constitute 77.8% of Malaysia’s total imports from the EU. Major EU trade partners with Malaysia are Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, France, and Belgium. These five countries accounted for about 74.5% of total EU-Malaysia trade in goods in 2020.

Trade in services

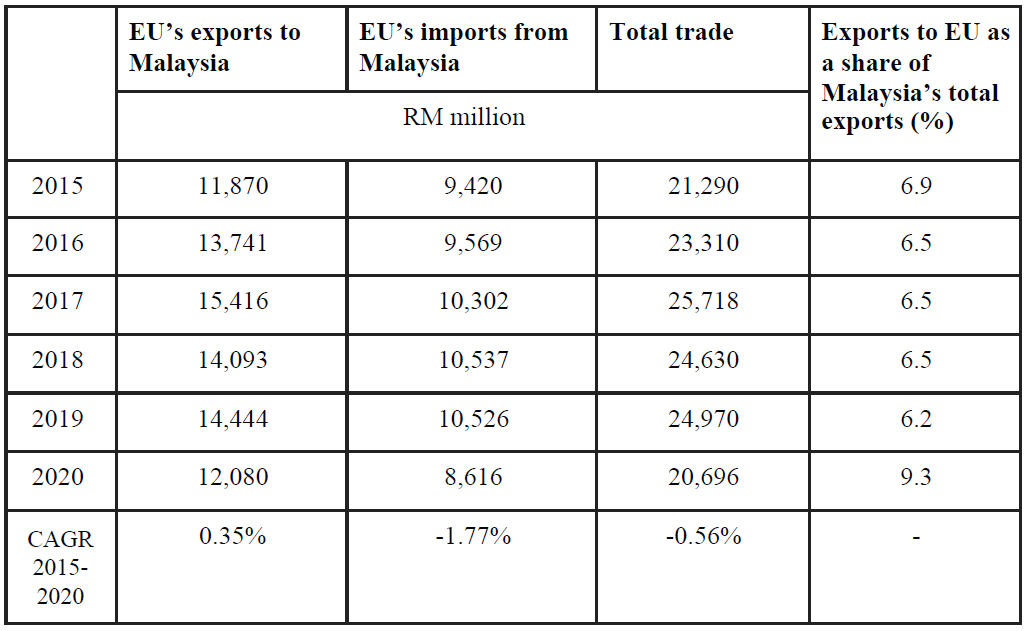

In 2020, the EU’s export of services to Malaysia was valued at RM12.1 billion, whilst EU’s import of services from the EU was around 8.6 billion (Table 3). In terms of Compounded Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) in 2015-2020, EU’s exports to Malaysia was 0.4% whilst Malaysia’s exports to the EU was -1.8%. However, export of services to EU as a share of Malaysia’s export of services in 2020 grew to 9.3% for the past five years ranging between 6.2% and 6.9%.

Table 3: EU-Malaysia exports, imports and total trade in services, 2015-2020

In terms of types of services traded, Malaysia’s exports to the EU are mainly other business services categories, telecommunications, computer and information services, transport and manufacturing services on physical inputs owned by others. These services constitute around 84.9% of the total services exported from Malaysia to the EU in 2020. Meanwhile, Malaysia imports other business services, transport, other services and telecommunications, computer and information services. These services constitute 89.4% of Malaysia’s total imports from the EU. Major EU trade in services partners with Malaysia are Germany, the Netherland, France and Italy. These four countries accounted for about 62.7% of total EU-Malaysia trade in services in 2020.

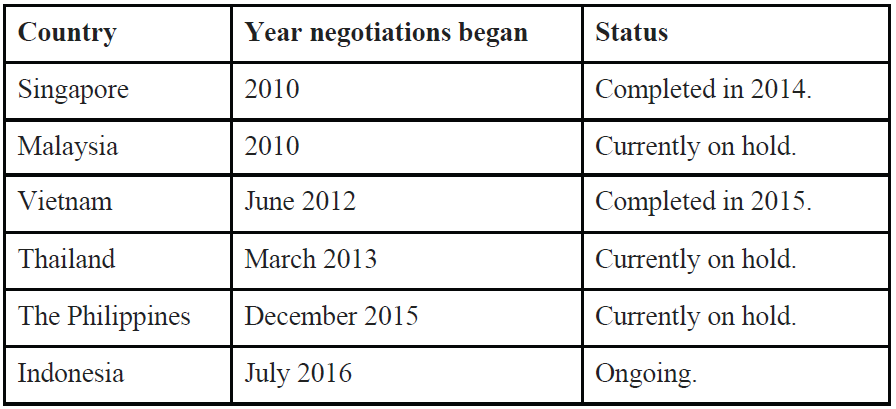

3. EU-Malaysia FTA

The Malaysian government started formal discussions to construct an FTA between Malaysia and the EU in September 2010[2]. Malaysia’s close neighbour, Singapore, also began similar negotiations with the EU that same year, followed by other ASEAN neighbours—Vietnam (2012), Thailand (2013), the Philippines (2015) and Indonesia (2016) (see Table 4).

Table 4: Status of FTA negotiations with EU by selected ASEAN members

According to the European Commission (2021), EU-Malaysia FTA negotiations were put on hold in April 2012 at the formal request of the Malaysian government[3]. Meanwhile, negotiations of EU-Singapore FTA which began in 2010 were completed in 2014. Negotiations for the EU-Vietnam FTA have likewise also been completed, in 2015.

Malaysia does not enjoy Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) benefits and therefore is expected to benefit from the elimination of tariffs through a negotiated FTA (Menon et al., 2018). The country should therefore step up efforts to strengthen exports and trade with the EU; trade data show a huge growth in Vietnam’s growing trade with the EU, especially in terms of exports, while Singapore maintains its long-standing position as EU’s largest trade partner in ASEAN.

In March 2017, negotiators from the EU and Malaysia agreed to resume FTA talks, but despite the confidence displayed by the EU and Malaysia, there is limited space for rapid progress. This is attributable to the problems that remain unresolved from 2012 (Spatafora, 2017).

Business groups are however lobbying the governments to resume negotiations, with EUROCHAM Malaysia and the Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers (FMM) recently signing a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to establish a joint Task Force to work for the realisation of the EU-Malaysia FTA (EUROCHAM, 2021). At the same time, the EU Ambassador to Malaysia indicated that EU-Malaysia trade which has been stable, may suffer a decrease in the future (The Edge, 2021). This echoes the point made by the European Commission that bilateral FTAs between the EU and ASEAN countries will serve as building blocks for a future EU-ASEAN agreement; such an agreement remains the EU’s ultimate objective.

4. Issues and challenges

A number of issues remain which make the completion of an FTA between Malaysia and the EU unlikely in the near future.

a) The issue of palm oil is central to Malaysia-EU relations. The EU is an important market for Indonesia and Malaysia, which supply about 17% and 13% of palm oil demand respectively (Devadason and Mubarik, 2020). The problem is related to the European Parliament’s vote for a Resolution on Palm Oil and Deforestation of Rainforests in 2017, and a ban on palm oil biofuels. In 2019, the EU adopted the Delegated Regulation for its second Renewable Energy Directive (RED II), which will phase out the use of palm oil as biofuel in Europe by 2030.

In early 2020, both Malaysia and Indonesia, the world’s second largest and the largest palm oil producers, respectively, filed a case against the EU using the World Trade Organization’s Dispute Settlement Mechanism. Thus, the issue of palm oil will remain an important item in EU-Malaysia FTA negotiations.

b) Among the issues that stalled FTA negotiations between the EU and Malaysia, several are specific to Malaysia. In terms of tariff, Ing and Cadot (2017) and Tham (2012) have highlighted the fact that there are high compliance costs in the automobile industry in Malaysia. Separately, there exist complex certification issues (from the perspective of foreign companies) in Muslim countries in ASEAN which includes Malaysia.

c) An issue that complicates the situation is the potential ASEAN-EU FTA. If completed, this will with all likelihood be a region-wide deal between a non-harmonized ASEAN region and an economically stronger harmonized EU (Devadason and Mubarik, 2020). As a rule, EU companies seek deeper economic engagement in the form of protection of their investments in ASEAN, through intellectual property rights and enforceable investment rules and regulations, and more participation in regional supply chains (Devadason and Mubarik, 2020).

d) In the past, there has been political pressure from EU countries on issues that Malaysia views seriously. For example, in the ‘Nutella tax on palm oil proposed by the French Parliament, Malaysia (and Indonesia) counteracted with threats to freeze talks on bilateral FTAs as well as purchases of French aircraft, satellites and other goods (Dreyer, 2016; Deringer and Lee-Makiyama, 2018).

e) There is concern that the political situation in Malaysia may hamper negotiations on the EU-Malaysia FTA. According to the European Commission, after the 2018 general elections in Malaysia, there has been no new position on the possible resumption of negotiations, either from the Perikatan Nasional government (2020-2021) or Barisan Nasional-led coalition government (2021-current).

However, recent statements by the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) suggest that the government has an intention to proceed with EU-Malaysia FTA negotiations (Bernama, 1 December, 2021).

5. Concluding remark

The healthy growth in trade and investments between Malaysia and the EU shows Malaysia’s expanding role within ASEAN, heightening its role in trade ties between the two organisations. This has to be seen against the background of other challenging issues such as the stalled EU-Malaysia FTA negotiations and contentions over palm oil and the environment.

The constant calls by different parties for EU-Malaysia FTA negotiations to resume highlight the importance of Malaysia in the regional economic context, as well as the expectations of the business community on both sides.

For list of references and appendix, kindly download the document to view.

Editor: Ooi Kee Beng

Editorial Team: Sheryl Teoh, Alexander Fernandez and Nur Fitriah (Designer)

[1] https://outoftheshadows.eiu.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/MY_MALAYSIA_PROFILE.pdf

[2] Eight rounds of negotiations were held, from December 2010 and September 2012 (MITI, n.d.).

[3] See p.2 in Spatafora, G. (2017) and Binder (2020) on the background of halt in talks.

You might also like:

![A Critical Need for Effective State-Federal Relations in Malaysia]()

A Critical Need for Effective State-Federal Relations in Malaysia

![Penang’s Socio-economic Transformation: Progress and Challenges]()

Penang’s Socio-economic Transformation: Progress and Challenges

![Key Issues to Consider in Heritage Preservation]()

Key Issues to Consider in Heritage Preservation

![The Digital Free Trade Zone – A Path to Inclusive Growth?]()

The Digital Free Trade Zone – A Path to Inclusive Growth?

![Counting Candidates: Towards Minimum 30% Women Representation on the Ballot]()

Counting Candidates: Towards Minimum 30% Women Representation on the Ballot