By Dr Tan Lee Ooi (Director of Research)

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The main challenge in becoming a data centre hub is the availability of water and electricity; the high resource consumption of data centres could strain existing capacity and put significant pressure on supply systems.

Introduction

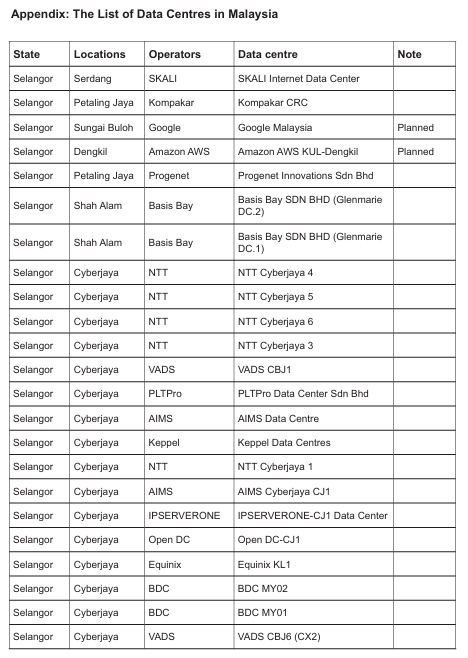

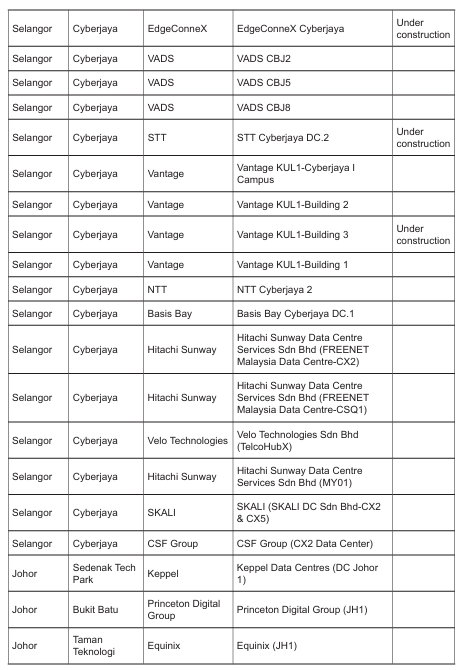

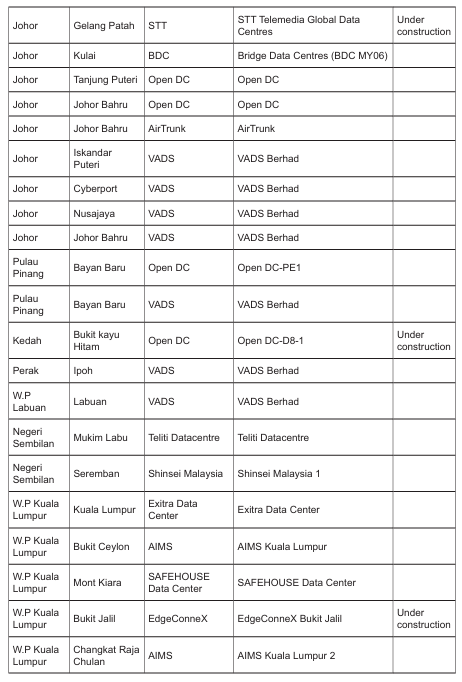

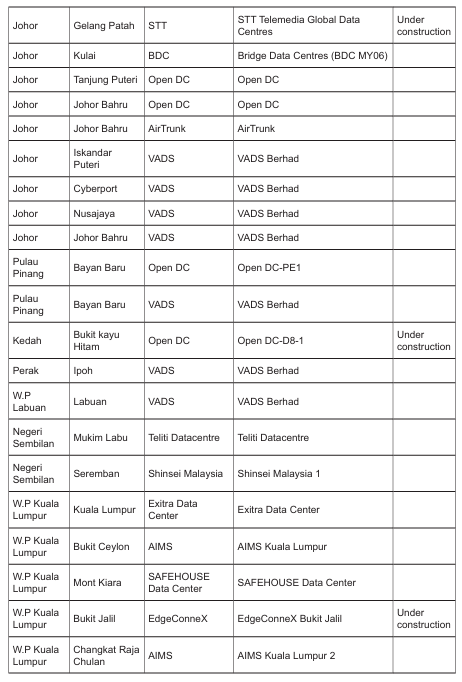

Malaysia is poised to become a major Southeast Asian hub for data centres. As of June 2024, the country hosts a total of 74 data centres (see Table 1). The domestic data centre market is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7%, reaching USD 1.6 billion by 2027, up from USD 1.1 billion in 2021 (MIDA, 2023). Over the past year, global industry leaders such as Google, Amazon Web Services, Microsoft, and Nvidia, driven by aspirations to explore the future potential of artificial intelligence, have announced long-term plans to invest in and establish data centres in Malaysia. This development was initially met with excitement by authorities, industry stakeholders, and the general public. While the positive sentiment persists, experts have begun to voice concerns about potential challenges.

Table 1: Data Centres by State in Malaysia [1]

Arguments Against Data Centres

The primary challenge of becoming a data centre hub lies in the availability of water and electricity resources. Analyses highlight the possibility that the consumption of these resources are so exorbitant that they could overwhelm current capacity and place significant pressure on supply systems.

Additionally, the high rates of consumption by data centres run counter to the nation’s decarbonisation goals, which are equally critical to its economic future. This situation underscores the urgency to explore innovative initiatives to maintain progress toward decarbonisation.

Critics have raised concerns about policies aimed at attracting and approving data centre investments, viewing them as potentially turning Malaysia into an industrial dumping ground for more advanced economies. Some argue that the technology transfer associated with data centre setups is minimal, and in fact offers limited benefits to the country. In response to these criticisms, authorities have emphasized their commitment to approving only high-quality investment projects that align with national priorities.

Revisiting Semiconductor Industry Experiences

A reflection on Malaysia’s industrialization history provides valuable insights into the current debate. Malaysia’s industrialization began with labour-intensive production, supported by the establishment of Free Trade Zones (FTZs) to attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). In its early stages, incentives such as ‘tax holidays through pioneer status, investment tax credits, tariff-free operations, and the provision of excellent basic infrastructure and security’ were introduced to attract the ‘first wave of export-oriented transnational corporations (TNCs) to Malaysia’ (Rasiah & Krishnan, 2020: 702).

However, the relocation of labour-intensive industries during this period brought challenges, including environmental degradation, exploitation of labour, and tax evasion by TNCs. Despite these issues, industrialization at this stage contributed to job creation, enhanced the basic infrastructure, and expanded the national economy, albeit primarily through low value-added and low-skilled industries.

To better reflect on Malaysia’s industrialization history, the semiconductor industry in Penang serves as an illustrative case study. Although the industry has recently garnered global attention, its roots date back to the establishment of the Free Trade Zone in 1971. According to Raja Rasiah (2017: 129), technological upgrading in the semiconductor industry can be understood through two dimensions.

The first dimension of upgrading is in ‘the functional elements of catch-up in which semiconductor firms integrate front-and back-end operations, while some relocate or upgrade to participate in R&D, integrated circuit (IC) design, and wafer fabrication’ (ibid). The second is the ‘deepening of the same functional activities as semiconductor firms absorb best practices, which include cutting edge inventory and quality control systems, and adaptive engineering and R&D support to upgrade functional activities to raise plant productivity’ (ibid).

Although Penang’s semiconductor industry has yet to achieve the highest levels of value creation, it has developed a robust ecosystem through decades of industrial experience. This ecosystem has positioned Penang and Malaysia to capitalize on shifts in the global landscape, particularly following the rise of geopolitical tensions between two superpowers. The trade war between the U.S. and China has prompted companies to relocate to Penang and Malaysia as part of a de-risking strategy (Ong, 2023).

In 2023, Penang attracted an impressive USD 12.8 billion in foreign direct investment (FDI), surpassing the total FDI received between 2013 and 2020 combined. In 2024, the inflow of FDI continues to surge, leading to the observation that ‘Penang is not short of FDI, but resources’ (Intan Farhana Zainul, 2024). Klaus Landhaeusser, Managing Director of Bosch Malaysia, highlighted that ‘Penang hosts the largest concentration of Bosch manufacturing facilities because of fundamentals such as regulatory familiarity, logistical efficiencies, supply chain synergies, and hiring processes that are already well-established’ (Seoow, 2024).

Data Centres’ Challenges and Opportunities

Deputy Minister of the Ministry of International Trade and Investment (MITI), Liew Chin Tong, has highlighted five major challenges facing the data centre industry during the recent Malaysia Cloud and Data Center Convention 2024:

1. How to create jobs, more importantly, high-value jobs.

2. Managing the water consumption.

3. Managing the energy consumption.

4. Managing issues of localisation.

5.Preventing speculative build (Liew 2024).

The surge in generative AI and the challenges related to data centre infrastructure are posing similar issues for data centres worldwide. In response, authorities are currently formulating updated guidelines on Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) and Water Usage Effectiveness (WUE). These updates aim to revise the Technical Code for Specification for Green Data Centres, initially developed in 2015 under the provisions of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998. The original Technical Code set minimum standards for green data centres, focusing on policies, systems, and processes to enhance energy efficiency and reduce the industry’s carbon footprint (MCMC, 2015: vi). In 2024, the framework has undergone revisions to further enhance regulatory guidelines (MCMC, 2024).

Malaysia has been selected by major tech companies for their global data centre strategic positioning and deployment. The country’s competitive advantage, including lower costs for land, water, electricity and labour, and business-friendly regulations, has seen Malaysia emerge as a powerhouse in the data centre industry. However, the authorities have recognized the constraints that may arise in the foreseeable future and have begun to reorient the influx of investments.

As a middle-income country, Malaysia is both a consumer and learner of cloud and AI technology. Similar to the early industrial period in the 1970s, there is a need to strike a balance in kick-starting a new future industry by allowing lower-value products to be developed initially. Becoming a regional data centre hub loads the country with a critical role amidst geopolitical contestation. The growing demand for carbon-friendly water and energy consumption will also pressure relevant agencies and industry players to innovate and address these challenges. This presents an opportunity to strengthen Malaysia’s digital capabilities through the involvement of a wide range of data centre actors, including companies specializing in structured cabling, cybersecurity infrastructure, high-end lighting, uninterruptible power supply, and cooling systems.

In revisiting the semiconductor industry’s experiences, we see that the data centre industry’s move up the value chain must be planned in stages. In the past, technological upgrading in the industry faced difficulties due to ‘lack of human capital development, the failure to attract Malaysians from abroad with the requisite tacit knowledge, lack of cohesion between governance instruments, firms, and organizations, and the absence of institutional coordination’ (Rasiah, 2020: 720). Therefore, the focus on technological upgrading must be facilitated concurrently with the formulation of regulatory procedures.

The Politics of Data Centres

The launch of the New Industrial Master Plan 2030 (NIMP 2030) represents Malaysia’s vision for a digital future. The inflow of FDI into the semiconductor industry and the recent push to attract investment for data centres have brought this vision closer to reality. The digital transformation of Malaysia’s economy is seen as a potential ‘second take-off’ for the nation. However, this vision exists within the context of an incomplete technological dream dating back to the 1990s. Beyond the need for regulation and technological catch-up strategies, there are also important social and political aspects to consider regarding the data centre industry.

Socio-cultural imaginaries for a nation striving for a promising digital future encompass collective visions, aspirations, and narratives that shape society’s understanding of what a technologically advanced future looks like. These imaginaries influence policy-making, resource allocation, and the integration of technology into daily life and national identity. In pursuit of a digital future, we trade our lands and resources to fulfil the digital ambitions of multinational technology companies riding the AI boom. This digital configuration, driven by tech giants will enhance the nation’s global integration and foster national pride, contributing to upward mobility.

The arrival of multinational technology companies has socio-political consequences for the Malaysian state. From a broader perspective regarding international relations as highlighted in a podcast by The Economist, ‘the data-centre boom has become a political battleground,’ where ‘the location of these digital warehouses is now crucial, not just for speed and proximity, but for the new struggles over data protectionism’ alongside ‘geopolitical considerations’ (Bird et al., 2024). Malaysia is politically entangled with Western ideologies following the influx of data centre investments, which prioritize personal privacy protection and individual freedom.

Looking at other regions, there have been growing protests across America and Latin America over the environmental and social impacts of data centres (Baptista & McDonnell, 2024; O’Donovan, 2024). The manifestations of the digital future will influence power relations within the country. These power dynamics highlight the need for inclusive planning and regulation that addresses both technological and social impacts across diverse communities. The focus should not solely be on economic benefits and regulatory needs. Therefore, the authorities must be prepared to manage these consequences, including public perception, as well as the political and environmental impacts of data centres.

Recommendations

1. Outline a clear framework on power consumption and resources utilization

There is an urgent need for a sustainable national policy for data centre growth that balances public benefits, resource conservation, and carbon-neutral goals, while maintaining a competitive edge in attracting major investments from big tech players. In addition to energy-efficiency standards, renewable energy mandates, and resource conservation standards, some countries also implement carbon offset programmes. All these initiatives must be planned in stages with clear, measurable, and time-bound goals. The authorities must also conduct periodic assessments with public reporting to ensure transparency and accountability.

2. Shape a data centre ecosystem that supports local economic development

The government is aware that data centres should create jobs and foster local expertise to drive economic development. Local optimization and the involvement of a wide range of local industry actors, including companies in cooling, wiring, cabling, lighting, chip manufacturing, and cybersecurity, should be incentivized.

3. Manage the politics of public perception regarding data centres

In the age of social media, it is essential to respond proactively to criticism with calm, factual details, and to reassure the public that expansion plans are well thought out, with careful consideration of local resources and infrastructure capacity. Regular updates on progress and impact should be provided to maintain transparency.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Malaysia’s pursuit of becoming a regional hub for data centres presents both significant opportunities and challenges. As the nation attracts major tech investments, it must navigate the complexities of balancing economic growth with environmental and social responsibilities. A sustainable national policy for data centre development is crucial, and needs to be one that emphasizes energy efficiency, resource conservation, and carbon neutrality, while also maintaining competitiveness. This policy must include clear, measurable goals and involve local industry stakeholders to foster economic development and job creation. Furthermore, managing the public’s perception is essential, requiring proactive communication and transparency about the impacts and benefits of data centre expansion. By addressing these challenges strategically and inclusively, Malaysia can realize its digital future while ensuring that the growth of the data centre industry aligns with broader national goals of sustainability, innovation, and equitable development.

Footnotes:

[1] This includes data centers planned and under construction in Malaysia as of June 2024. See Attachment 1 for the full list of data centres in Malaysia prepared by Hajar Ariff, Statistician in Penang Institute.

References

Baptista, Diana & McDonnell, Fintan. 2024. “Thirsty data centres spring up in water-poor Mexican town”. The Globe and Mail, 6 September 2024. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-thirsty-data-centres-spring-up-in-water-poor-mexican-town/, accessed 31 October 2024.

Bird, Mike et al. 2024. “How the data-centre boom became a political battleground”. The Economist, Money Talks: Business and finance, podcats. https://www.economist.com/podcasts/2024/10/10/how-the-data-centre-boom-became-a-political-battleground, accessed 31 October 2023.

Intan Farhana Zainul. 2024. “Penang is not short of FDI, but resources”. The Edge Malaysia, 24 Jul 2024. https://theedgemalaysia.com/node/719136, accessed 30 October 2024.

Liew, Chin Tong. 2024. “Navigating the Challenges and Opportunities of the Data Centre Industry”. Liew Chin Tong page, 24 October 2024.

https://liewchintong.com/2024/10/24/navigating-the-challenges-and-opportunities-of-the-data-centre-industry/, accessed 30 October 2024.

Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission. 2015. Technical Code: Specification for Green Data Centres. MCMC MTSFB TC G004:2015, developed by Malaysian Technical Standards Forum Bhd & register by MCMC, 18 December 2015. https://mcmc.gov.my/skmmgovmy/media/General/pdf/MCMC-Green_Data_Centres.pdf, accessed 30 October 2024.

Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission. 2024. Technical Code: Specification for Green Data Centres – First Revision. MCMC MTSFB TC G004:2024. https://mtsfb.org.my/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/MTSFB2307R1_Specifications-for-Green-Data-Centre-First-Revision_PC-VERSION.pdf, accessed 30 October 2024.

MIDA. 2023. “Malaysia, the next regional data centre hub”. Malaysian Investment Development Authority, 17 Apr 2023. https://www.mida.gov.my/mida-news/malaysia-the-next-regional-data-centre-hub/, accessed 31 October 2024.

O’Donovan, Caroline. 2024. “Fighting back against data centers, one small town at a time”. The Washington Post, 5 October 2024. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2024/10/05/data-center-protest-community-resistance/, accessed 31 October 2024.

Ong, Wooi Leng. 2023. “Catching the Winds of Change: Penang and Malaysia Need to Make the Most of Global Manufacturing Trends”. Penang Institute, monograph. https://penanginstitute.org/publications/monographs/catching-the-winds-of-change-penang-and-malaysia-need-to-make-the-most-of-global-manufacturing-trends/, accessed 31 October 2024.

Rasiah, Raja. 2017. “The Industrial Policy Experience of the Electronics Industry in Malaysia”. In Page, John, and Finn Tarp (eds), The Practice of Industrial Policy: Government—Business Coordination in Africa and East Asia (Oxford, 2017; online edn, Oxford Academic, 20 Apr. 2017), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198796954.001.0001, accessed 16 Oct. 2024.

Rasiah, Raja & Krishnan, Gopi. 2020. “Industrialization and Industrial Hubs in Malaysia”. Oqubay, Arkebe, and Justin Yifu Lin (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Industrial Hubs and Economic Development, Oxford Handbooks (2020; online edn, Oxford Academic, 6 Aug. 2020), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198850434.001.0001, accessed 23 Oct. 2024.

Seoow, Juin Yee. 2024. “Penang leads Malaysia’s semiconductor charge”. Think China, 2 Jul 2024.https://www.thinkchina.sg/technology/big-read-penang-leads-malaysias-semiconductor-charge, accessed 31 October 2024.

Appendix: The List of Data Centres in Malaysia

You might also like:

![Counting Candidates: Towards Minimum 30% Women Representation on the Ballot]()

Counting Candidates: Towards Minimum 30% Women Representation on the Ballot

![Stuck in Traffic: Why Malaysia Does Not Have a Motorcycle Ride-hailing Sector]()

Stuck in Traffic: Why Malaysia Does Not Have a Motorcycle Ride-hailing Sector

![Covid-19 in 2022: A More Optimistic Landscape Emerges]()

Covid-19 in 2022: A More Optimistic Landscape Emerges

![TVET in Malaysia: Current Situation, Challenges and Recommendations]()

TVET in Malaysia: Current Situation, Challenges and Recommendations

![A Critical Need for Effective State-Federal Relations in Malaysia]()

A Critical Need for Effective State-Federal Relations in Malaysia