Executive Summary

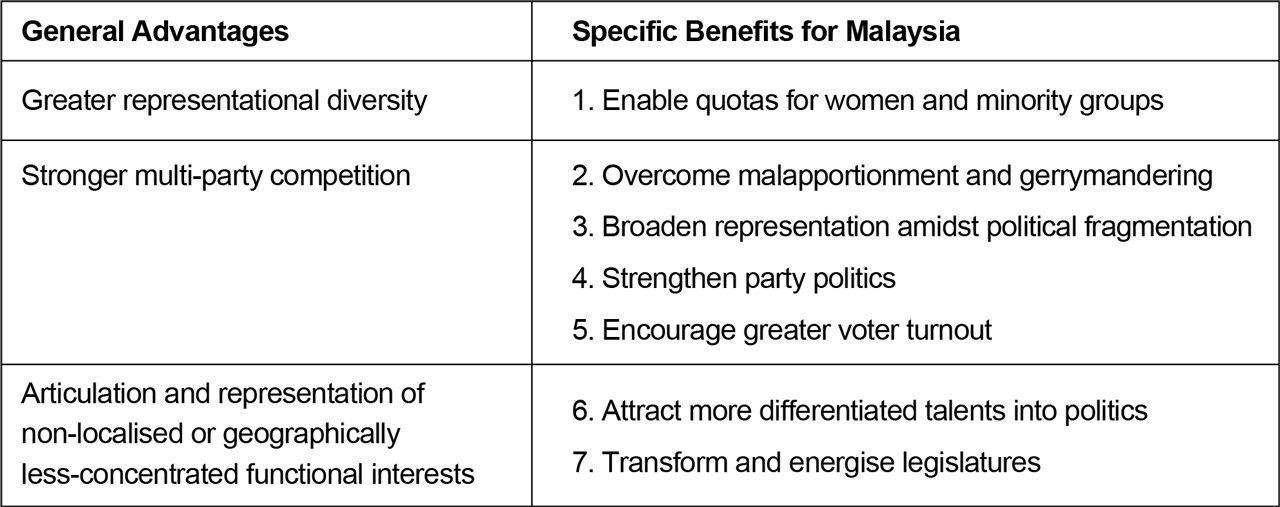

- Multi-member constituencies are unknown to the Malaysian electoral system. However, such an innovation may facilitate greater representational diversity, stronger multi-party competition, and the articulation and representation of non-localised or geographically less-concentrated functional interests, and be just what the Malaysian democracy needs

- Specifically, what is needed are “party-list, at large” multi-member constituencies that may simply be called “non-constituency seats” (NCSs)

- NCSs may bring seven benefits:

- Enable quotas for women and minority groups;

- Overcome malapportionment and gerrymandering;

- Broaden representation amidst political fragmentation;

- Strengthen party politics;

- Encourage greater voter turnout;

- Attract more differentiated talents into politics;

- Transform and energise legislatures.

- NCSs can be introduced at the state level without any amendments made to the Federal Constitution

- If the proportion of NCSs is small, it is advisable to impose a 100% women quota, resulting in “Women-Only Additional Seats” (WOASs)

Introduction

Constitutionally speaking, what is the single characteristic that best defines Malaysia’s electoral system? Some might argue that it is the plurality outcome, or “the candidate for a constituency who polls the greatest number of valid votes cast by the electors of the constituency shall be deemed to be the elected member for that constituency”. However, that would be inaccurate since plurality outcome is only provided at a lower level under Section 13 (1) of the Elections Act 1958.

The only electoral system feature that is constitutionally-entrenched is single-member constituency, i.e., “one member shall be elected for each constituency”, as stated in Articles 116 and 117 which govern the federal and state constituencies.

This means that, without even amending the Federal Constitution, the Malaysian electoral system can be amended from the British First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) to the French Two-Round System (TRS) or the Australian Alternative Vote (AV).

Both the French and Australian alternatives necessitate a majority winner, thus affirming the legitimacy of the election outcome because the winner will always have more supporters than opponents. Such a feature is worthy of consideration if Malaysian politics grow too fragmented.

Multi-member Constituencies are Common in the World

For the purpose of this study, it is pertinent to consider the constitutional feature, single-member constituencies in contrast to its alternative, multi-member constituencies.

In Malaysia, multi-member constituencies are mostly found in associations, clubs and political parties where members or delegates elect some number of committee members without specific portfolios.

Often, different candidates may form teams and present “menus” (chaidan in Chinese or chai in Malay) to score not just a personal victory but to gain collective control of the organisation as well.

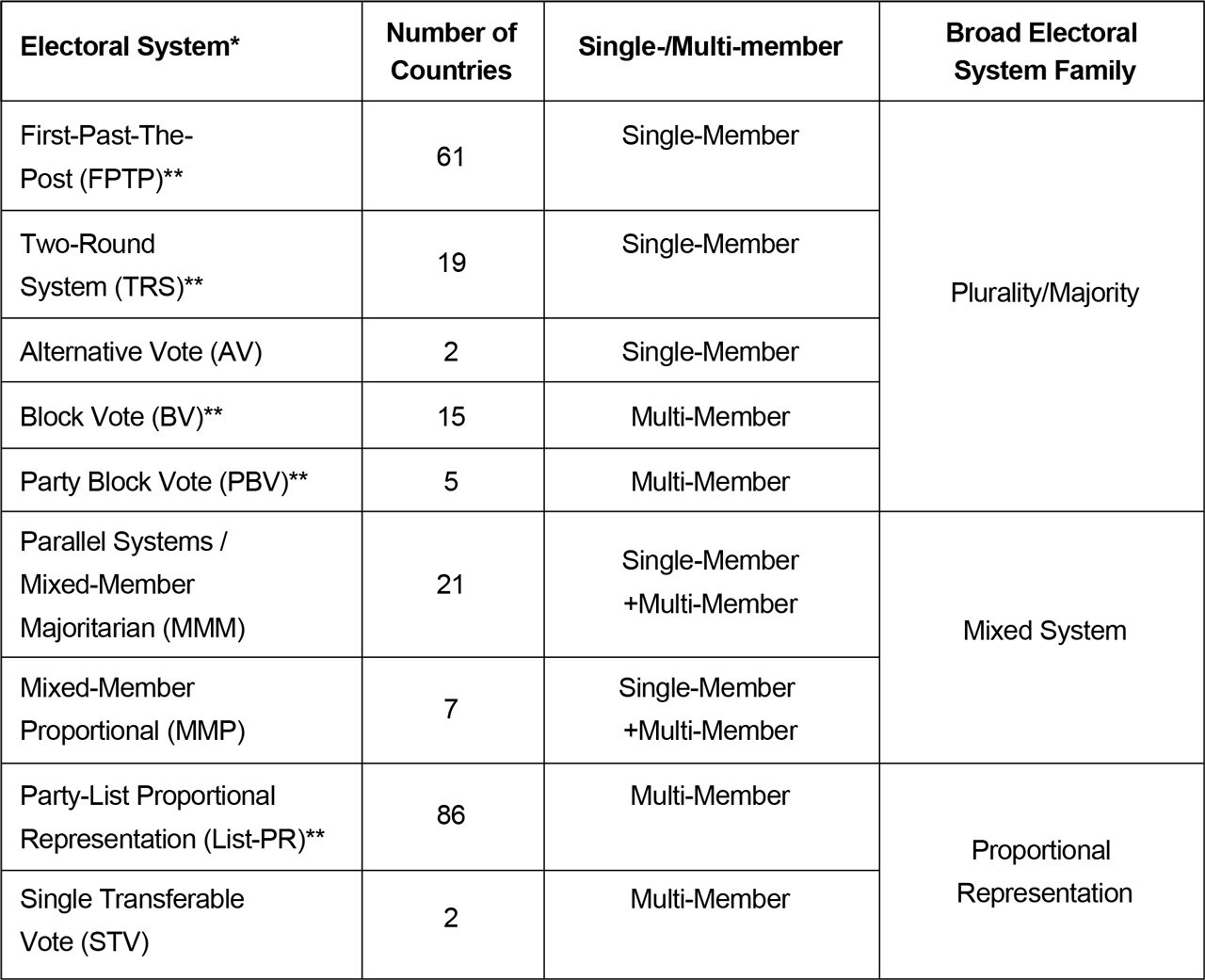

Today, 134 countries in the world use – fully or partially – multi-member constituencies for their national parliaments. Of these, 86 employ “Party-List Proportional Representation” (List-PR), two have a “Single Transferable Vote” (STV) system, 15 use “Block Vote” (BV), five apply “Party Block Vote” (PBV), 21 adopt the “Parallel Systems or Mixed-Member Majoritarian” (MMM) and seven implement “Mixed-Member Proportional” (MMP) (Table 1)[1].

In comparison, 67 countries employ exclusively single-member constituencies under FPTP, TRS or AV.

Table 1: Electoral Systems Used in National Parliaments in the World

**12 countries use one of these combinations: FPTP and BV (7); FPTP and PBV (2); FPTP, PBV and List-PR (2); FPTP and List-PR (3); TRS and PBV (1).

Source: International IDEA (http://www.idea.int/data-tools/question-view/130355 and further communication).

Once a hallmark of the British political system, FPTP has been dropped by some British Commonwealth countries. In 1996, New Zealand adopted the German-style Mixed-Member Proportional (MMP) by adding a dominant List-PR component to its FPTP elections.

Closer to home, Singapore added a PBV component called Group Representation Constituencies (GRCs) to its FPTP system in 1988. Today, 76 out of 89 Singaporeans parliamentarians are elected through GRCs and only 13 through single-member constituencies.

While New Zealand and Singapore had moved their electoral systems in opposite directions, the former being more proportional while the latter went more for a “winner-takes-all” outcome, their changes underline the advantages of having multi-member constituencies.

Party-List, Multi-member, “Non-Constituency Seats” (NCSs)

Contingent on the specific electoral systems, multi-member constituencies may have three key advantages.

The first potential advantage is greater representational diversity. While candidates in single-member constituencies can claim to represent many groups and interests at the same time, at the end of the day, only one of them will emerge as the winner.

In reality, most winning candidates come from dominant socio-economic, ethno-religious, cultural, and gender groupings, resulting in a narrowly-based political class.

By electing more than one representative from a constituency, diversity can be easily imposed. This works especially when voters are to vote for teams as in List-PR and Singapore’s GRC, instead of individual candidates as in Ireland’s STV.

List-PR can have multiple layers of quotas for otherwise under-represented groups such as women, ethnic minorities, disableds and youths while every GRC in Singapore has a specified ethnic minority group, from which a candidate must be included by the contesting parties.

The second potential advantage is stronger multi-party competition in legislature and checks and balances in governance.

Whereas single-member constituencies are by default a “winner-takes-all” approach that is susceptible to malapportionment and gerrymandering, multi-member constituencies under List-PR or STV can offer very different outcomes.

Multiple seats in a List-PR or STV constituency will be divided among different parties based on their vote shares. Such constituency-level multi-partyism is likely to lead to multi-partyism at the national level, which automatically checks executive dominance and induces inter-party power-sharing in one way or another.

While consensual politics may affect efficiency and effectiveness negatively, it is both desirable and necessary that democratic tendencies thrive — and are seen to thrive — in divided societies.

However, in Singapore’s GRCs where voters choose between teams, and the winning team takes all the seats in the constituency, the outcome can be even more “winner-takes-all” than FPTP and more adversarial to multi-partyism.

Lastly, with greater geographical scope, multi-member constituencies enable articulation and representation of non-localised or geographically less-concentrated functional interests, involving issues such as gender, environment, and social inclusion.

Voters concerned with such matters may be too scattered to hold sway in any single-member constituency, where local issues tend to take precedence. However, if a number of single-member constituencies are merged to become a multi-member constituency, some of these issues may attract enough votes to gain representation. Moreover, the larger its geographical scope, the more members a constituency can elect, which may theoretically increase the diversity of the candidates nominated by parties.

What is the ideal size of a multi-member constituency? Maximally, a state and even the whole country can be made an “at large” constituency. “At large” constituencies are ideal if we want the system to be inclusive of as many concerns as possible.

Hence, to reap the three aforementioned advantages, what we need specifically are party-list, multi-member constituencies, which ideally should be “at large”.

However, when lawmakers represent the entire state or a country, the term “constituency” becomes meaningless, so we may call them as “non-constituency” representatives, which we now turn to consider, as a contrast to the existing constituency representatives.

The Case for NCSs in Malaysia

The NCSs can bring seven benefits to our political system. An overview linking the three general advantages and the seven specific benefits for Malaysia is shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Benefits of Non-Constituency Seats

1. Enabling Quotas for Women and Minority Groups

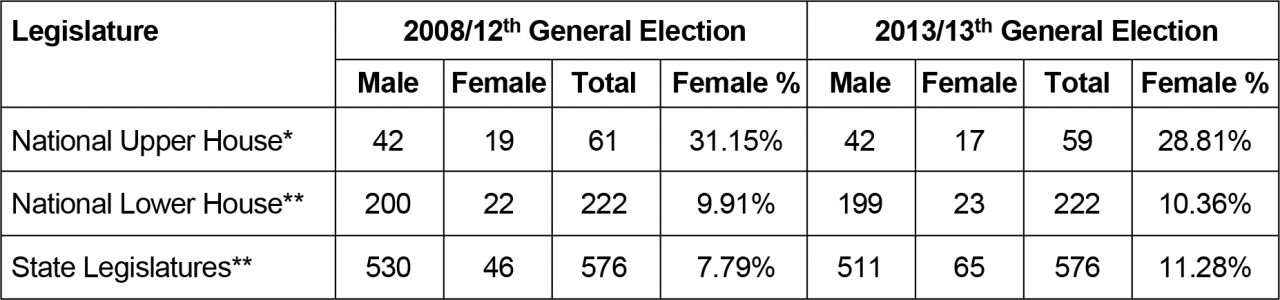

One clear benefit of introducing NCSs is that it allows for the immediate implementation of a gender quota. In 2017, Malaysia ranks 157th out of 193 countries in terms of women representation in national parliament, placing her only above Myanmar, Brunei and Thailand in Southeast Asia. Even after the political tsunami in 2008, only one out of every 10 parliamentarians is a woman, and the state-level records are not much better (Table 3).

Calls for political parties to field at least 30% women candidates have been issued for decades but these have largely fallen on deaf ears. Beyond patriarchy, the single-member nature of FPTP constituencies makes gender quota a personal zero-sum game for male incumbents or aspirants at the constituency level. By contrast, the “gender interval” format for the NCS candidate list – whereby every one out of X candidates has to be a woman – would be less personal to male politicians.

Table 3: Severe Under-representation of Women in Malaysian Legislatures, 2008-2013

**as per the immediate election results, excluding any by-election changes.

Source: Statistics on Women, Family and Community Development 2013 – 2016, Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development.

Beyond gender, multiple layers of quotas can equally be imposed on the party lists to ensure diversity of otherwise under-represented groups such as aboriginal peoples, other ethnic minorities, disableds, youths, and retirees.

In fact, group quotas may be necessary to arrest communal anxieties over under-representation. For example, some quarters dismissed the revival of local elections on the false ground that the Malay-Muslim community may be unrepresented or under-represented in city and municipality councils. Multi-member constituencies with minority quotas – in full or in part – may serve as a simple solution to address such concerns.

2. Overcoming Malapportionment and Gerrymandering

The chronic and flawed practices of malapportionment and gerrymandering of constituencies have distorted Malaysia’s election outcomes, so much so that in 2013, the Pakatan Rakyat won only 40% of parliamentary seats and was denied power despite winning 51% of popular votes. The electorate’s mandate was simply overturned by the electoral system.

While the Election Commission’s latest proposals on constituency redelineation are being rigorously challenged in court by the state governments of Penang and Selangor and voters from other states, a legal remedy does not provide a guaranteed solution. To overcome systemic seat-vote disproportionality across parties, Malaysia should move away from FPTP. This may be achieved at least partly through adopting a hybrid system such as New Zealand’s MMP. With sufficiently many lawmakers elected via “at large” constituencies, there will simply be no room for gain from malapportionment and gerrymandering.

3. Broadening Representation amidst Political Fragmentation

By default, single-member constituencies cannot give any representation to all losers. It is even worse for multi-corners in FPTP elections, as the losers may actually constitute the majority. For example, in an evenly-fought three-cornered fight, the winner may emerge with only 34% support even though (s)he is opposed by the remaining 66%. And the legitimacy of his or her victory may be endlessly challenged.

FPTP elections hence pose a political risk if the country’s politics is highly fragmented. While multi-member constituencies cannot eliminate or discourage fragmentation, they can instead displace it from electoral to legislative arenas, by broadening representation in the house.

4. Strengthening Party Politics

The mandate given to FPTP candidates is essentially personal even though they are normally nominated by political parties and their seats won on party platforms. Legally, there is nothing to stop an elected representative in almost every state in Malaysia from defecting to another party and holding on to his or her seat. As in the cases of Sarawak (1966), Sabah (1994) and Perak (2009), governments may even be brought down by the defection of lawmakers, be this driven by inducement, ideology and/or coercion.

By contrast, party-list candidates fill up the NCSs purely based on party mandate. If a non-constituency representative defects from his or her party, (s)he cannot take the NCS with him or her to another party. Moreover, when political parties have strong control over their representatives, voters too will have stronger control over the political parties as their electoral verdict is more likely to be honoured until the next poll is called.

In short, party-list NCSs can make politics more stable and predictable.

5. Encouraging Greater Voter Turnout

Casting a ballot makes no difference if the election outcome is foregone. Rational voters in stronghold constituencies may therefore opt to stay home instead. Electoral certainty is however reduced when there are more seats to be filled. Hence, having an additional tier of NCSs can encourage greater voter turnout, especially in stronghold areas.

6. Attracting More Differentiated Talents into Politics

Demanding constituency works expected of constituency representatives may turn some people away from pursuing a political career. In Malaysia, elected representatives are often expected to be in close touch with their constituents for so-called ‘KBSM’ events: Kahwin (Wedding), Bersalin (Childbirth), Sakit (Sickness) and Mati (Death) or they might be seen as aloof and disconnected from the grassroots.

NCSs may therefore attract a different pool of talents: NGO activists, policy experts, professionals, technocrats, and public intellectuals, who may not thrive at FPTP elections but nevertheless have great potential to contribute to better legislation and policy-making.

7. Transforming and Energising Legislatures

Malaysian lawmakers are often awarded merit by voters for their constituency work and their ability to bring home development projects, rather than their legislative or policy work. These biased impressions are partly due to the relatively short legislative sessions – accumulatively 10-12 weeks for Parliament and 2-3 weeks for State Assemblies – and the near absence of committee work outside assembly. Such over-emphasis of constituency service weakens the Legislative’s power to check and balance the Executive.

Introducing non-constituency representatives will force a recognition of non-constituency representative work. It can give an extra push to the legislative reform agenda, at least for longer legislative sessions, and the establishment of more committees.

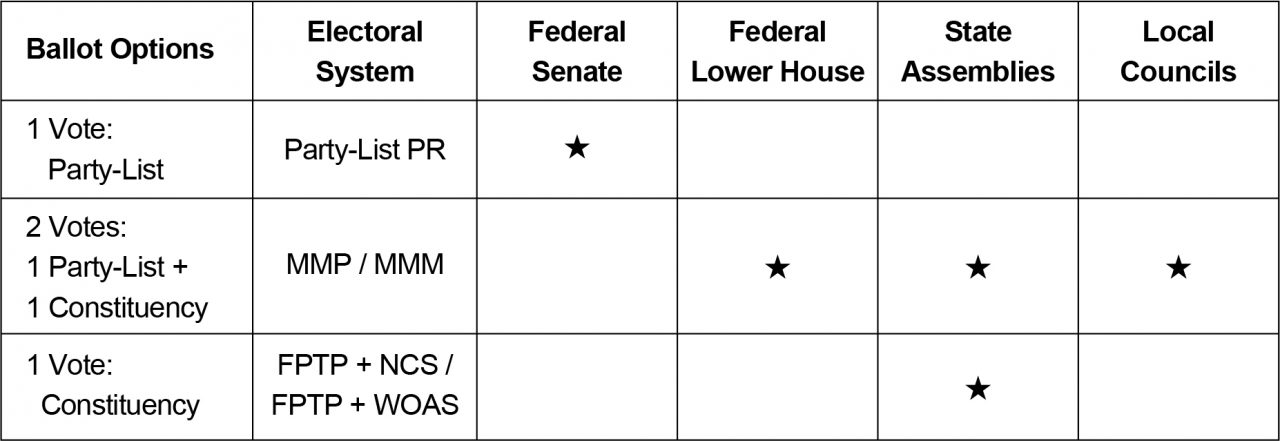

The Options for Inserting NCSs

NCSs can be introduced either as a stand-alone system, namely through a List-PR or as the PR component of a hybrid system. Both options may be considered for elected representations at all levels: Federal Senate (Dewan Negara), Federal Lower House (Dewan Rakyat), State Assemblies and Local Councils (Table 4).

Table 4: Options for Non-Constituency Seats in Malaysia’s Legislative Bodies

At Senate level, List-PR is a feasible option if elections are to be introduced. Every state may constitute an “at large” constituency to elect 2-3 senators, with additional members elected from a nation-wide constituency.

For Dewan Rakyat and State Assemblies, it would be better to maintain some continuity and have a hybrid system. Voters will be given two votes, one for their constituency FPTP representative and another for their Party-List representative. This system would work well for local council elections too.

Depending on the desired degree of proportionality, the new system may take the form of a Mixed-Member Proportional (MMP) or a Mixed-Member Majoritarian (MMM) system.

Anticipating these changes, whether in the form of a List-PR or the MMP/MMM hybrid system, the Federal Constitution will first have to be amended to allow for multi-member constituencies.

While the Federal Government has not displayed much of an appetite for such changes, possibilities do exist at the state level.

The Federal Constitution does not directly prohibit NCSs. In fact, Section 14 of the Sabah State Constitution allows the state government to appoint up to six “nominated members” besides its 73 elected members.

In Penang and Selangor, the state governments can similarly amend their state constitutions to add “nominated members” to their “elected members”. However, unlike Sabah, these “nominated” seats should be allocated to parties based on their vote share. In other words, the constituency votes in FPTP elections will be aggregated and used as proxy for party votes in MMP/MMM. While short of installing a MMP or a MMM, these states can still realise much of the seven benefits brought by these NCSs.

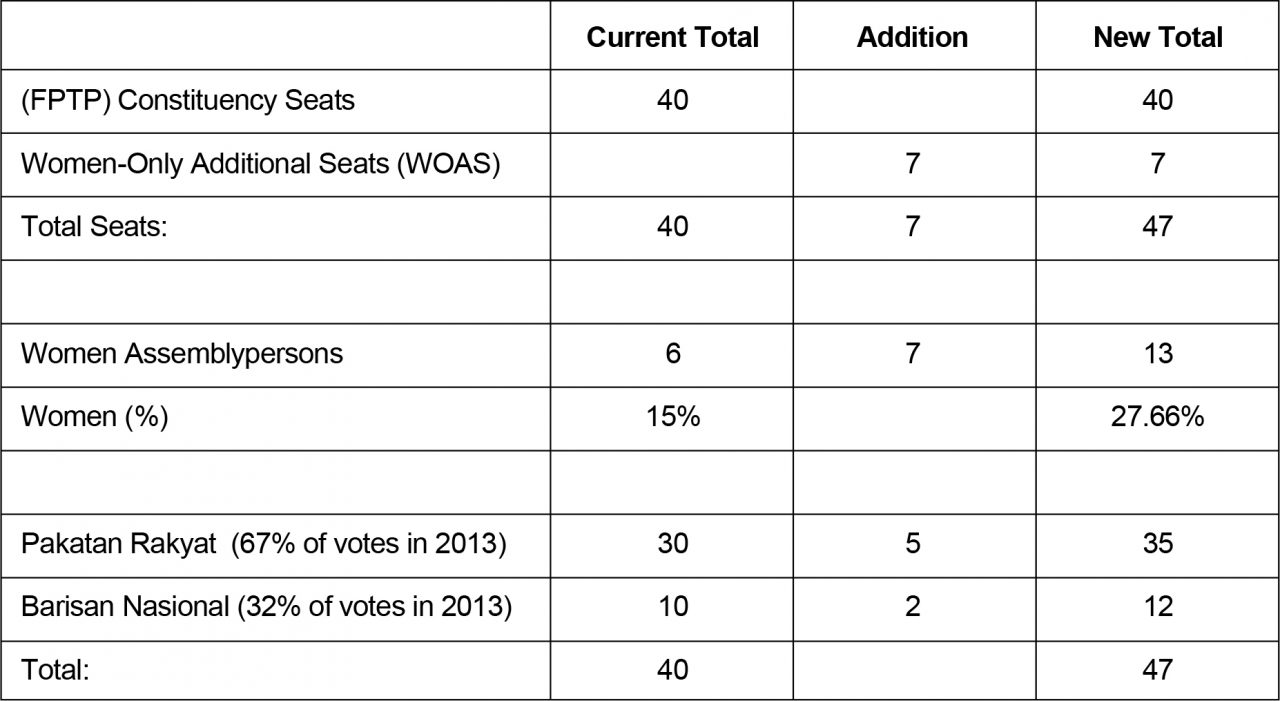

Women-Only Additional Seats (WOASs)

An important thing to remember is that for the benefits to be significant, the proportion of NCSs should be sufficiently large, for example, 30%. If a gender quota of 50% is imposed on the 30% NCSs, there will be a minimum 15% women representation. If a smaller proportion of NCSs – say 15% – is preferred, then it makes sense to impose a 100% women quota to ensure a critical mass of women non-constituency lawmakers.

This women-only variant of NCSs may then be called “Women-Only Additional Seats” (WOASs), which has been mooted by the Penang Women’s Development Corporation (PWDC) and Penang Institute (PI).

A national conference on gender and electoral reform, co-organised by the two state bodies last August, has called for the introduction of MMP in the long run and that of WOAS at the state level as an immediate alternative.

The Penang Legislative Assembly currently has 40 constituency representatives. If seven WOAS seats are added, they will constitute 15% in the expanded house of 47. Assuming WOAS will be introduced by next state election, and the outcomes of the last state election are to be repeated, the next assembly would have six women constituency representatives and seven WOAS representatives, or 27.66% women representatives in the expanded legislature.

Since Pakatan Rakyat won 67% and Barisan Nasional 32% of votes respectively in the last election, five of the seven WOAS would go Pakatan Rakyat’s way while Barisan Nasional’s seats would also increase by two.

This would marginally improve Barisan Nasional’s representation from 10/40 (25.00%) to 12/47 (25.53%). It would also increase Pakatan Rakyat’s lead over the former by 30-10 to 35-12 (Table 5).

Table 5: Allocation of WOAS Assuming a Replay of the Last State Election in the Next State Election

Correcting gender balance need not be a battle of the sexes. WOAS or its general form NCS can be a win-win solution for women, men, ruling parties, the opposition, and citizens.

[1] The numbers added up are larger than 134 because 12 countries have a combination of two or three systems.

Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng Editorial Team: Regina Hoo, Lim Su Lin, Nur Fitriah, Ong Wooi Leng

You might also like:

![Breaking Old Habits is Vital for Malaysia’s Mainstream Newspapers]()

Breaking Old Habits is Vital for Malaysia’s Mainstream Newspapers

![Can Batu Kawan Industrial Park be the Silicon Valley of the East?]()

Can Batu Kawan Industrial Park be the Silicon Valley of the East?

![The Covid-19 Disruption Highlights the Neglected Nature of Arts and Culture Sector in Malaysia]()

The Covid-19 Disruption Highlights the Neglected Nature of Arts and Culture Sector in Malaysia

![Tracking Malaysia’s Development Expenditure in Federal Budgets from 2004 to 2018]()

Tracking Malaysia’s Development Expenditure in Federal Budgets from 2004 to 2018

![Stuck in Traffic: Why Malaysia Does Not Have a Motorcycle Ride-hailing Sector]()

Stuck in Traffic: Why Malaysia Does Not Have a Motorcycle Ride-hailing Sector