Executive Summary

- Implementing public whipping does not require the passing of the amended bill of the Syariah Courts (Criminal Jurisdiction) Act 1965 [Act 355] – popularly known as Bill 355 – in Parliament. Act 355 merely governs how many lashes of the whip are to be meted out, not how the corporal punishment is to be carried out

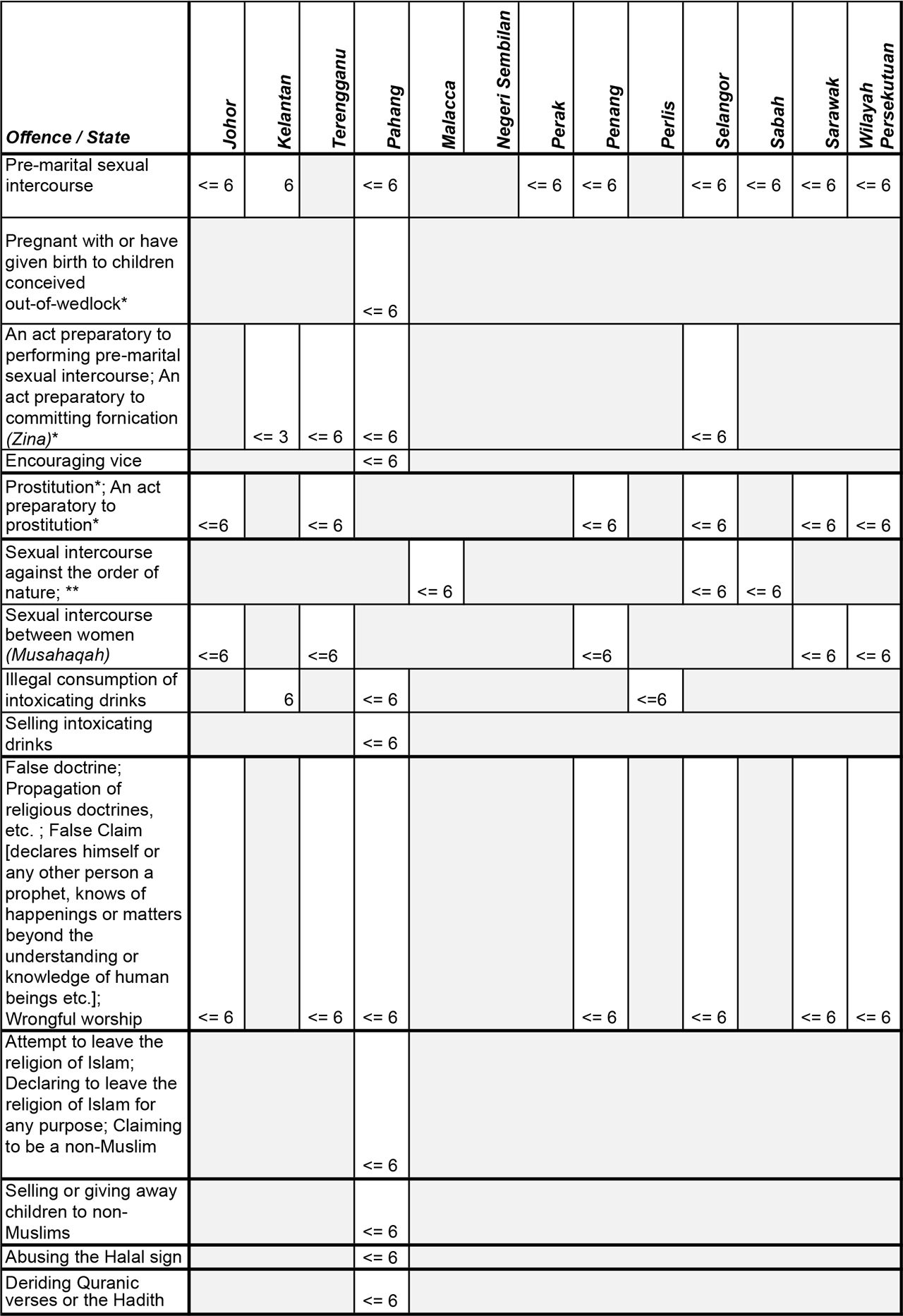

- Whipping (up to 6 lashes) is meted out as punishment for a wide range of Syariah criminal offences in all states, except Kedah. At the most extensive end, in Pahang, whipping can be meted out to Muslims for selling alcohol, abusing the Halal sign, and conceiving children out-of-wedlock

- Public whipping has been carried out three times in Sabah under subsection 125(3)(c) of its Syariah criminal procedural law, which is as many times as in Kelantan prior to the latter’s amendments of its Syariah criminal procedural law. Unless this subsection is declared unconstitutional for being inconsistent with subregulation 132(1) of the Prison Regulations 2000, nothing stops the Syariah Court from ordering public whipping

- Kelantan’s amended Syariah law now makes public whipping mandatory. In other words, the Syariah Court loses its discretionary power to not order the whipping sentence to be executed in public

- Mandatory public whipping may become a national trend if other Malaysian states follow in Kelantan’s footsteps. This may have far-reaching implications and warrants the conduct of in-depth research and open discourses on the matter

1. Misperception that Public Whipping Requires the Passing of Bill 355 by Parliament

On July 12, 2017 the Kelantan State Legislative Assembly passed amendments to its Kelantan Syariah Criminal Procedure Enactment 2002 which now allows, among others, Syariah criminal offenders to be whipped in public.

But some parties are of the opinion that the corporal punishment remains unenforceable as long as Bill 355 has not been approved by Parliament.

This stems from a misperception that the whipping sentence is only found in the state’s Syariah Criminal Code II 1993 (2015), i.e., 100 lashes for unmarried offenders of fornication (zina), 80 lashes for unsubstantiated accusation of fornication or sodomy (qazaf), and 40 to 80 lashes for illegal alcohol consumption. Indeed, such whipping sentences cannot be enforced without amendment to the Syariah Courts (Criminal Jurisdiction) Act 1965 [Act 355] – popularly known as Bill 355 – as the number of whip lashings is currently capped at six.

However, the execution of whipping sentences and criminal jurisdiction are two distinct issues and are subject to different statutes. The former is subject to the Syariah Criminal Procedure Enactment 2002 in Kelantan and similar laws that govern other Malaysian states, excluding Kedah which does not incorporate the whipping sentence in its menu of punishments for Syariah criminal offenders.

Unless declared “null and void” by the court, the provisions in and amendments made to the Syariah criminal procedural laws on whipping sentences applies to the enforceable Syariah criminal offences.

2. Overlapping of the Syariah Criminal Enactments and the Penal Code (Act 574)

Indeed, some of the provisions in the Syariah criminal enactments cannot be enforced as the offences governed by them are also governed by federal laws, especially with regards to the Penal Code (Act 574).

Syariah laws as a state matter is grounded on Item 1, List II (State List), the Ninth Schedule of the Federal Constitution which reads:

“… creation and punishment of offences by persons professing the religion of Islam against precepts of that religion, except in regard to matters included in the Federal List; …”

And Item 4 in the Federal List:

“Civil and criminal law and procedure and the administration of justice.”

Further, Article 75 also stipulates that:

“If any State law is inconsistent with a federal law, the federal law shall prevail and the State law shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be void.”

This clearly indicates that when there is an overlap between any state Syariah criminal enactments and federal laws, the provisions of the former become void.

The Penal Code (Act 574) covers at least the following offences: injuring or defiling a place of worship (Section 295), words or acts that cause disunity or feelings of enmity on grounds of religion including accusing others of having left their faith (Section 298A), enticing girls below 16 years old (Section 361), abduction and abducting a woman with marital motives (Sections 362 and 366), exploiting others for prostitution (Sections 372, 372A, 372B and 373), incest (Sections 376A and 376B), unnatural sex with animals or humans (Sections 377 and 377A), and enticing a married woman (Section 498).

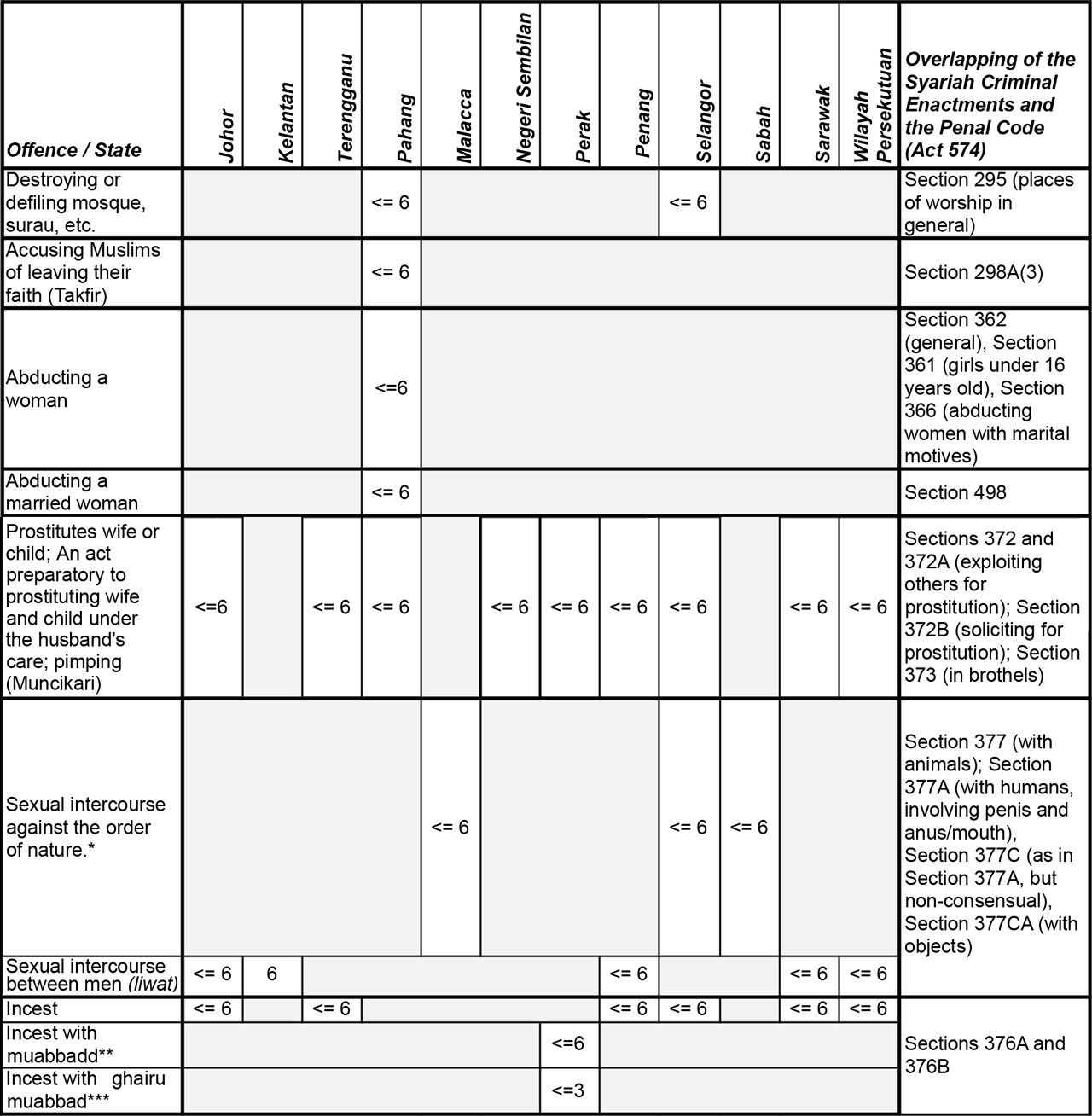

As Syariah law provisions governing these offenses are void because of the overlap with the Penal Code, the whipping sentences as well as other forms of punishment cannot be meted out by the Syariah courts (See Table 1).

Table 1: Syariah Criminal Offences with Unenforceable Whipping Sentences [Syariah criminal offences become void due to an overlap with the Penal Code (Act 574)]

** Those who are forever prohibited such as parents and siblings

***Those who are prohibited because of existing marital ties such as brothers/sisters in-laws

3. Enforceable Whipping Sentences for Syariah Criminal Offences

Many Syariah criminal offences carry enforceable whipping sentences, be they mandatory or discretionary. For example, under the Syariah Criminal Code Enactment (Kelantan) 1985, the offences of fornication (zina) (Section 11) and the consumption of intoxicating drinks (Section 25) carry six lashes of the whip each as mandatory punishment, on top of discretionary punishments of a fine and imprisonment. In contrast, the offence of initiation of sexual activities preceding intercourse (muqaddimah zina) carries only the discretionary punishments of a whipping sentence of not more than three lashes, a fine and imprisonment.

Table 2 lists all Syariah criminal offences that carry enforceable whipping sentences for all states, except Kedah.

Table 2: Syariah Criminal Offences with Enforceable Whipping Sentences

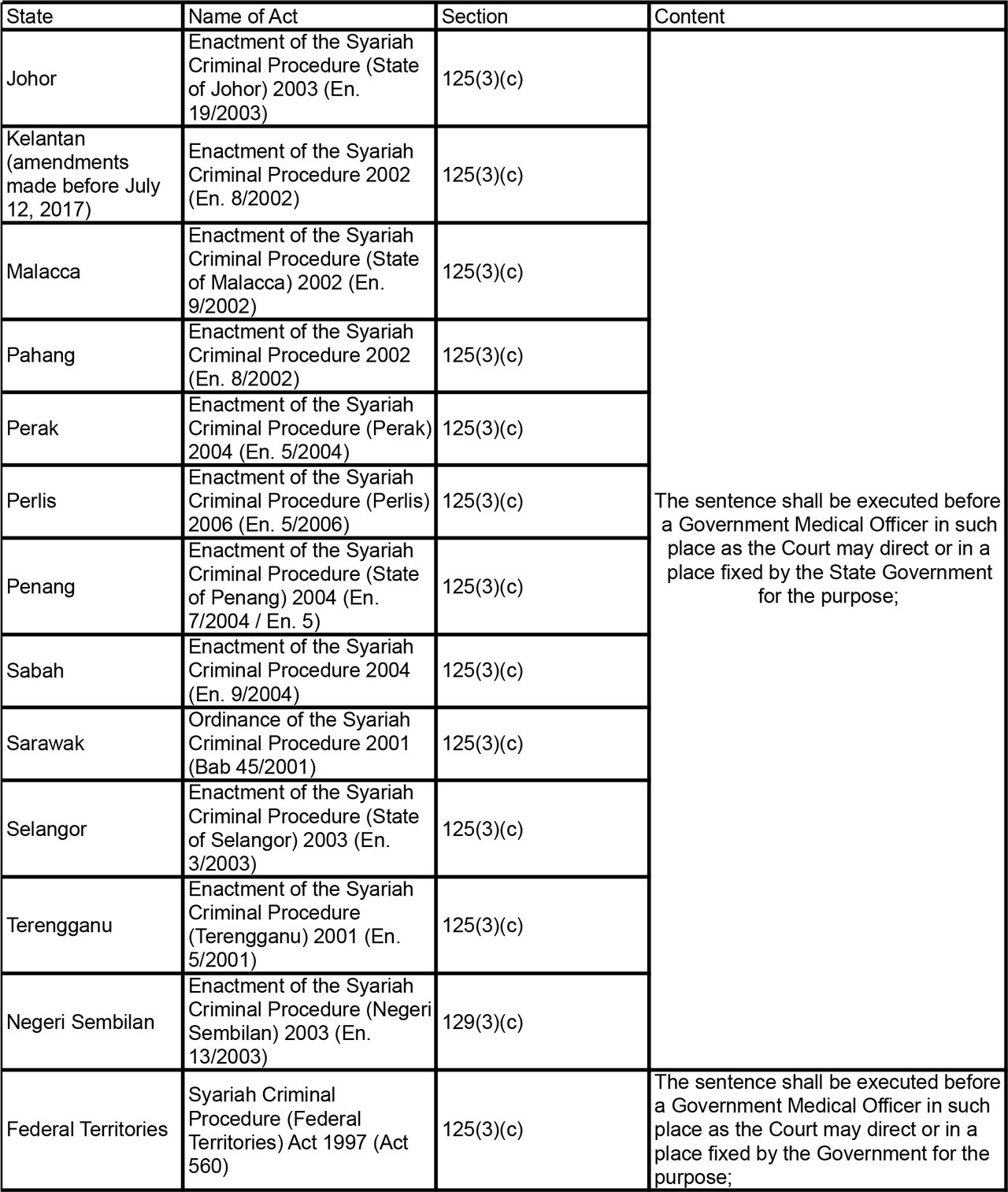

4. The Existing Method for Executing Whipping Sentences

Kedah notwithstanding, the execution method for whipping sentences is uniform in all states, including the Federal Territories, though the names of their criminal procedural laws generally vary. With the exception of Negeri Sembilan and the Federal Territories which differ slightly in their numberings and provisional contents, the rest of the states have identical paragraphs under identical numberings: subsection 125(3)(c). For ease of discussion, where relevant, subsection 125(3)(c) is used to represent the provision for all states, and not just Kelantan (see Table 3).

Table 3: The Method of Executing Whipping Sentences According to Syariah Criminal Procedural Laws Across States

The uniformity in this aspect indicates that what can be done in one state can also be done in other states. It equally implies that amendments made to Kelantan’s Syariah Criminal Procedure Enactment 2002 may be followed by other states.

5. Public Whipping under the Existing Subsection 125(3)(c)

Is public whipping – in the sense of a whipping sentence being executed in an “open” manner “to be witnessed by members of the public” – allowed under the existing subsection 125(3)(c) in Kelantan and other states?

According to Nizam Bashir, a lawyer practicing both Syariah and civil laws, public whipping is unconstitutional because whipping has to be done in prison and prison is a federal matter (Item 3 on the Federal List on the Ninth Schedule). His basis is subregulation 132(1) of the Prison Regulations 2000, a by-law under Prisons Act 1995 (537)[2], which reads:

“Any punishment lawfully imposed on a prisoner may be carried out in any prison, or partly in one prison and partly in another.”

This means subsection 125(3)(c) of the Syariah criminal procedural laws is hollow. The Syariah courts cannot choose a venue other than a prison for the execution of whipping sentences, insofar as the offenders are slapped with both imprisonment and whipping.

What if the offender is only sentenced to whipping? The existing subsection 125(4) reads:

“In the case where the offender is sentenced to whipping only, then he shall be dealt with as if he is sentenced to imprisonment until the sentence is executed.”

This means all offenders sentenced to whipping are by default prisoners and the Prison Regulations 2000 presides over the Syariah criminal procedural laws in the states.

Public whipping however has been carried out in practice.

According to the news report “Sabah Syariah Court Records 3 Open Whipping Sentences” published by BorneoPost Online on July 15, 2017[3] , the State Syariah Chief Justice Datuk Jasri @ Nasip Matjakir revealed three public whipping cases that took place in the Tawau Syariah Court in 2014 and 2016 for the offence of fornication (zina).

He explained, “The 2014 case which involved a woman, was supposed to be held in Tawau prison. However, the offender was only punished with whippings, so it could not be done in the prison area.

The whipping sentence is done at the request of the offender. Hence, the prison’s side recommended for the sentence to be exercised in open court.” [4]

The 2016 case has weightier implications. A couple convicted of a similar offence was openly whipped in a civil court “following the presence of a group of seminar participants who wanted to see the execution of the Sharia whipping sentence.” [5] The public whipping was recorded on video and uploaded to Youtube (URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YVs53S86das) with the names of the offenders publicised in the subtitles.

Datuk Jasri @ Nasip Matjakir defended the viral video on the grounds that “it could help the public to understand in differentiating the Syariah whipping sentence, whether it is cruel or rather educating”.[6] He added that “the execution of the open whipping sentence was enough to help the government to explain on the proposed amendments in Bill 355”.[7]

Unless it is declared as being unconstitutional, subsection 125(3)(c) remains on the books and the Syariah courts can rely on it to order public whipping as in the Tawau cases, without any need for amendments.

6. Implications of Amending Subsection 125(3)(c) In Kelantan

If the cases in Sabah have shown that subsection 125(3)(c) is sufficient for the Syariah Courts to order public whipping until it is declared unconstitutional, what then does the amendment passed in Kelantan entail?

The original subsection 125(3)(c) gives Syariah Courts the discretionary power to decide if whipping sentences should be carried out in public, while Kelantan’s amendment of its Syariah Criminal Procedure Enactment 2002 makes public whipping mandatory. In other words, the Kelantan Syariah Court no longer has the discretionary power to NOT order public whipping witnessed by four Muslim males.

The amendment modified subsection 125(3)(c) from the following:

“the sentence shall be executed before a Government Medical Officer in such place as the Court may direct or in a place fixed by the State Government for the purpose.”

to

“the sentence shall be executed in an open manner before a Government Medical Officer of the

Islamic faith and witnessed by a group of Muslims which consists of no less than four males in such place as the Court may order as gazetted by the State Government for the purpose.”

“In an open manner” according to this section is the execution of whipping sentences that can be witnessed by a group of Muslims.[8]

Note: The English text, here and in Table 4, is a translated version of the official Malay text. As such, the author regrets any inaccuracy this may result in. Unfortunately, the amended bill has not been made available to the public by the Kelantan Legislative Assembly and the author has gained only partial access.

In specific terms, this amendment highlights two significant changes. First, the “open manner” of the execution of whipping sentences to be “witnessed by a group of Muslims which consists of no less than four males” is made mandatory. Second, with the provision “as gazetted by the State Government for the purpose”, the Syariah Court can only choose amongst places gazetted by the State Government while it could direct the place or choose the places fixed by the State Government.

If subsection 125(3)(c) is changed in the other states in accordance to the Kelantan model such that uniformity emerges as in the status quo, then the Syariah Courts in all the states – except Kedah – will lose their discretionary powers to only mete out whipping sentences and not order their executions in public. Thus far, the Menteri Besar of Terengganu Datuk Seri Ahmad Razif Abdul Rahman9 and the Mufti of Pahang Datuk Seri Dr Abdul Rahman Osman[10] have expressed interest or intention to follow in Kelantan’s footsteps.

7. Other Changes Made to Section 125 in Kelantan

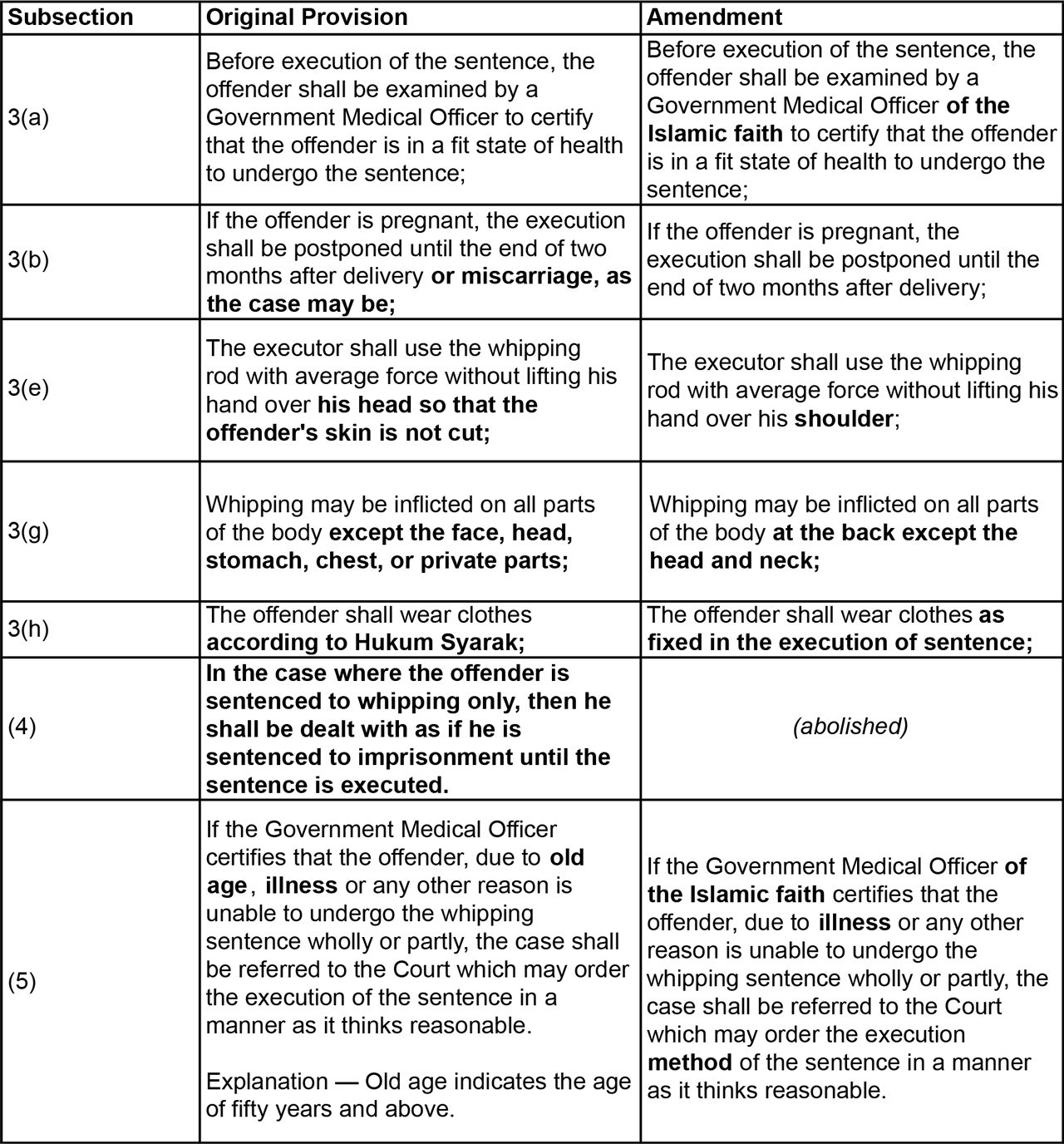

Other than subsection 3(c), the Kelantan State Legislative Assembly also amended six other subsections/paragraphs and abolished a subsection under Section 125 (see Table 4).

The most significant change is the abolition of subsection 125(4), which means offenders who face whipping sentences only can no longer be imprisoned before their execution. While this lightens the sentence, will it also be used to argue that public whipping under subsection 125(3)(c) is constitutional, as long as offenders are sentenced to whipping only?

The execution of whipping sentences is also made lighter with the new paragraphs 3(e) and 3(g). The executor can only lift his hand as high as his shoulder, not his head and the front parts of the neck and shoulders are expressly excluded from whipping.

At the same time, the sentencing is also made arguably heavier. First, under the new subsection 5, old age – 55 years and above – is no longer a ground for exemption from whipping sentences. Second, under the new subsection 3(b), the two-month postponement after a miscarriage is no longer in effect for pregnant offenders.

Table 4: Other Changes Made to Section 125 of Kelantan’s Syariah Criminal Procedure Enactment 2002

8. Conclusion

Public whipping can be implemented under the existing legal framework, ie, subsection 125(3)(c) of the Syariah criminal procedure laws in all states, except Kedah. Unless whipping is declared “null and void”, the three aforementioned cases of public whipping in Tawau, Sabah have shown that the Syariah Courts do indeed have the power to order their public execution.

Public whipping does not need the passing of Bill 355 in Parliament which concerns only how many lashes of the whip can be meted out, not how the sentencing should be executed. The overlapping of the Syariah criminal enactments and the Penal Code (Act 574) renders whipping sentences unenforceable for certain Syariah criminal offences such as sexual intercourse between men (liwat), and accusing Muslims of leaving their faith (takfir). However, Syariah criminal offences such as fornication (zina) and the illegal consumption of alcohol do carry the enforceable punishment of the whip.

Clearly, Kelantan’s amendment of subsection 125(3)(c) is not to give the Syariah Court the discretionary power to order public whipping; such power is already present under the existing provision. The real purpose of the amendment is to make public whipping compulsory such that the Syariah Court is denied the discretionary power not to order it.

If the Kelantan amendment is to be followed by other states – a likely development considering the current uniformity of subsection 125(3)(c) across the states – public whipping may soon become a national trend. Considering the fact that some states apply the whipping sentence widely – Pahang for example, metes out whipping sentences to Muslims who sell alcoholic drinks, abuse the Halal sign, and are pregnant with or have given birth to children conceived out-of-wedlock – this national trend will have far-reaching implications not just to Muslims, but the entire nation as well.

Therefore, the significance of mandatory public whipping warrants in-depth research as well as the holding of open, rational, and wise discourses involving the entire society. All views based on facts and logic must be considered. Amongst others, three sets of pertinent questions stand out. First, from the perspective of constitutional laws, is the current subsection 125(3)(c) unconstitutional because all offenders sentenced to whippings are by default prisoners and subregulation 132(1) dictates that whipping prisoners can only be done in prison? Would the removal of subsection 125(4) make public whipping under subsection 125(3)(c) constitutional, if offenders are sentenced with only whipping?

Second, from the perspective of Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh), is public whipping a religiously mandatory constant (tsawabit) or a subject variable according to social context (mutaghayyirat)? Between punishing and educating, which advances public interests (maslahah) more effectively? What is the priority (awlawiyyat) accorded to public whipping in attaining the higher purposes (maqasid) of Shariah laws? Operationally speaking, between the Syariah Court and the State Legislative Assembly, which body would know better and should be given the power to decide if public whipping is necessary?

Third, from the perspective of the social sciences, does evidence support the hypothesis that the tougher the punishment, the lesser the crimes and social ills? For example, Pahang applies whipping sentences on the widest range of Syariah criminal offences while Kedah does not. Is the rate of Syariah criminal offences in Pahang significantly lower in the statistical sense compared to Kedah?

In approaching the last set of questions, we can perhaps heed the wisdom of Dr Jasser Auda: “We need to enhance and activate dialogues (hiwar) that are more humanist and inclusive. Dialogues that underline universal issues that are important and where the entire human race shares the frustration. When we speak about social leaders, we should articulate issues with critical discourses that appreciate the issue of humanity comprehensively, holistically, and most of all, orientated on the parameters (dhawabit) of true Islamic considerations.”[11]

[1] The text of this law can be downloaded from: http://www2.esyariah.gov.my/esyariah/mal/portalv1/enakmen2011/Eng_enactment_Upd.nsf/f831ccddd195843f4825 6fc600141e84/f2c9904aa43a3eb14825703c00213991?OpenDocument . Other Syariah laws referred to in this paper are also available at: http://www.esyariah.gov.my/portal/page/portal/A53FADC208F449278B791C1F6796192C.

[2] Both the Act and the Regulations are downloadable at http://www.prison.gov.my/portal/page/portal/english/undang2_en

[3] Borneo Post (2017), “Sabah Syariah Court records 3 open whipping sentences”, Borneo Post, July 15, 2017, URL: http://www.theborneopost.com/2017/07/15/sabah-syariah-court-records-3-open-whipping-sentences/

[4] The explanation that whipping cannot be done in prison is inconsistent with Subsection 125(4) of the Syariah Criminal Procedure Enactment (Sabah) 2004 which is also employed in other states. It stipulates that offenders who are sentenced to whipping only are to be imprisoned until the execution of the whipping sentence. The prison authority’s suggestion for the whipping to be carried out in open court might be to spare the offender the derived imprisonment.

[5] Borneo Post (2017), “Sabah Syariah Court records 3 open whipping sentences”, Borneo Post, July 15, 2017, URL: http://www.theborneopost.com/2017/07/15/sabah-syariah-court-records-3-open-whipping-sentences/

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] The Malay text reads: “hukuman hendaklah dilaksanakan secara terbuka di hadapan seorang Pegawai Perubatan Kerajaan yang beragama Islam dan disaksikan oleh sekumpulan orang Islam yang tidak kurang dari empat orang lelaki di mana-mana tempat yang diperintahkan oleh Mahkamah sebagaimana yang diwartakan oleh Kerajaan Negeri bagi maksud itu;

Huraian:

“secara terbuka” mengikut maksud seksyen ini ialah perlaksanaan hukuman sebatan yang boleh disaksikan oleh sekumpulan orang Islam.”

[9] Malaysiakini (2017), “MB: T’ganu ikut Kelantan jika semua setuju” , Malaysiakini, 14hb Julai 2017, URL: https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/388484

[10] Malaysiakini (2017) “Pahang mungkin boleh ikut Kelantan, kata mufti”, Malaysiakini, July 14 2017, URL: https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/388584

[11] Jasser Auda (2017), working paper titled “Negara Madani dan Referensi dalam Prinsip Islam dan Maqasid Shariah” [Civil State and References in the Principle of Islam and Maqasid Shariah]”, presented in the Nadwah al-‘Ulama Lin-Nahdah al-Jadidah (NUNJI) Conference, on February 5, 2017, at the Auditorium Kompleks Belia Shah Alam, Selangor.

Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng Editorial Team: Regina Hoo, Lim Su Lin, Nur Fitriah, Ong Wooi Leng