Abstract: Governments are often criticised for being big, bloated and bureaucratic, and calls are continually made for them to become smaller, leaner and nimbler. The architecture of modern governments however naturally tends them towards being big, bloated and bureaucratic. There are at least three reasons for this: (1) modern governments addressing wicked problems; (2) the multi-level organisation of modern governments; and (3) the multi-actor composition of modern government. Wicked problems are defined as those that require a joint approach where each additional actor contributes positively to solving a particular problem. Being multi-level on the other hand presents opportunities for contest and manoeuvring between levels, while the multi-actor situation enlarges the span of governments while reducing oversight and control. Taking it as a given that these design features tend modern governments towards being big, bloated and bureaucratic, efforts to transform modern governments should be focused on turning these seeming negatively effects towards being positive. In short, the call should be for modern governments to be catalytic, capable and consistent.

Honing the Human Advantage

When a potential investor to Malaysia reaches out to the Malaysian Government for facilitation, he will find himself facing a choice of 31 investment promotion agencies (IPA), each with varying incentives, interests, and influence. These agencies are for him what makes up the “Malaysian Government”. However, each of these on its own, is unable to speak on behalf of the “Malaysian Government”. For the potential investor then, navigating these agencies is one of adventurous discovery. It is small consolation that the same is experienced by local business owners interested in engaging the Malaysian Government on their digitalisation journey. According to a study by the World Bank (Robert, 2022), “more than a dozen ministries have been directly involved in providing such support to varying extents through about two dozen agencies”. A journey of discovery indeed.

Indeed, the concept of dealing with just “one government” while rightfully aspirational, remains elusive. And more so in recent decades with the proliferation of dreaded 3B-governments; Big, Bloated, and Bureaucratic, i.e. governments who spend, hire and do more. In the case of Malaysia, the government’s debt to GDP ratio was 83.3% in 2023 (2022: 83%) [1]; the civil service-to-population ratio was at 1:20 in 2019 (2003: 1:32) [2]; and government effectiveness scored a percentile of 79.25 in 2022 (2017: 74.76) [3] But why are governments Big, Bloated and Bureaucratic? A holistic view of the architecture of the modern government suggests certain explanations. Specifically, 3 characteristics are identified which tend governments towards being big, bloated, and bureaucratic. First, governments deal with wicked problems. Second, governments are organised in a multi-level manner, and third, governments are multi-actor systems.

Architecture of the Modern Government

1. Governments face an expanding scope of wicked problems

From social services and regional economic development to climate change and emergency management, the scope of public service delivery is continuously expanding. In short, modern governments are expected to do more. Often, they are an actor of last resort, called into play when a situation has reached an impasse, and the cost too big for things to fail. Detrimentally, governments are depicted as necessary for fixing market failures leading often to situations where gains are privatised but losses socialised (Mazzucato, 2013). The nature of these services in turn, are underpinned by wicked problems. Made popular by (Rittel & Webber, 1973), wicked problems are a category of complex problems which do not have a set of optimal solutions [4]. Due to their inherent complexity, wicked problems are riddled by uncertainty and divergence. Stakeholders cannot even agree on how such problems are to be framed 5, and this in turn results in the parallel implementation of a slew of policy solutions which may diverge matters significantly with regards to the end goal (Head, 2022).

The wicked problem of crime is an example. While the Home Ministry might frame crime as a public security problem, the Health Ministry on the other hand frames crime as a public health problem. One problem, two diagnoses. Similarly, the Ministry of Trade might take a free market approach to economic development while the Ministry of Entrepreneurship takes a protectionist approach. In truth, the “right” framing probably lies somewhere along these dichotomies, or on a multidimensional plane. Indeed, wicked problems necessitates a joint approach given that no one actor 6 has sufficient problem-solving capacities to solve them (Conklin, 2005). This can be in the form of technical knowledge, monetary resources, or even official legitimacy, where each additional actor brings with them unique problem-solving capacities. The more “wicked” the problem, the more actors required. The more “wicked problems” you have, the more actors you have.

Modern governments therefore find themselves in a conundrum; the necessary approach to effectively address wicked problems is also the reason why they tend towards becoming increasingly big, bloated and bureaucratic.

2. Governments are organised in a multi-level manner

In its common understanding, multi-level governments are understood through a federalism approach. This signifies the dispersion of power across government jurisdictions vertically at the local, state, federal and international levels. Hooghe and Marks (2003) distinguishes these levels as being a general-purpose jurisdiction; non-intersecting; and having a limited number of jurisdictional levels. Federalism as a doctrine promises governance with clear boundaries of authority and scope.

In practice, however, federalism often deviate from theory, and levels of jurisdictions are intertwined and not easily disentangled. We see this in the existence of the Concurrent List in the Ninth Schedule which enumerates matters shared by both the Federal and State Governments. The governance of local governments is also instructive. While primarily administered by their respective State Governments, local governments are governed by the Federal Government through the Local Government Act 1976.

In the policy arena, jurisdictions between levels of government then become grounds for contest and manoeuvring. We see for example how the Penang State Government resorted to alternative means of financing for the Light Rail Transit project in the absence of support by the Federal Government due to political misalignment [7]. Conversely, the Federal Government intervened with supplementary funding to the Kelantan State Government to address long-standing challenges in water supply by a seemingly apathetic State government. What could have been a more straight forward planning and execution of a transportation system in Penang by the Federal Government, and water supply management in Kelantan by the State Government as custodians of their respective matters has ended up as contested projects with additional resources being spent on manoeuvring [8]. In the case of Penang, we see this in the shifting plan of the Penang South Island (PSI) in reaction to availability of Federal funding [9]. In the case of Kelantan, we observe the additional monitoring required to ensure that funds transferred to the State are spent as intended [10]. This is despite what can be argued as a comprehensive list of matters which delineate Federal and State powers in the Malaysian Constitution. Indeed, Bakvis (2021) argues that the distribution of powers in federalism “… is not simply a matter of a set of rules and institutions but the interaction between endogenous and exogenous events, political mobilisation and leadership.” In turn, we find that these interactions of contest and manoeuvring costs additional resources, tending governments towards being big, bloated and bureaucratic at the crossing between each jurisdiction.

3. Governments are multi-actor in its composition

Having its roots in the New Public Management (NPM) paradigm from the 1980s onwards, the proliferation of “agencies” has become commonplace among governments. Intended to be specialised units adopting more private-sector type management practices, agencies refer to a variety of semi-autonomous public service organisations located at arm’s length from the core of government (Osborne, 2009). We identify them here as public service organisations (PSO).

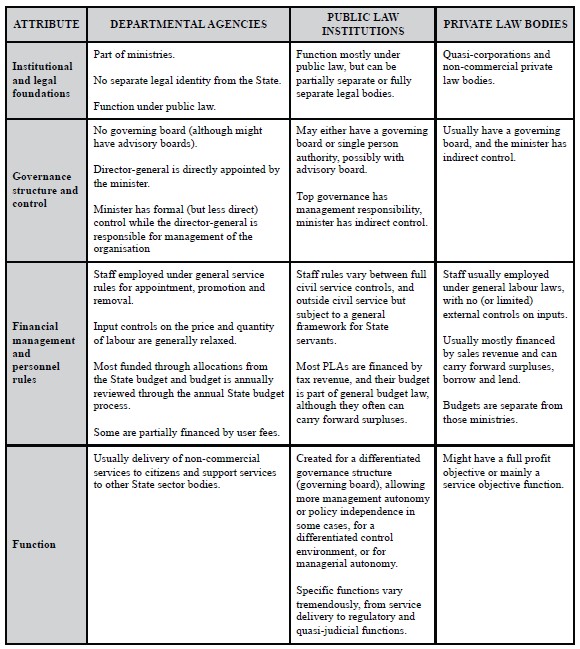

Owing to their vast variety, the OECD suggests three classifications for PSOs based on their legal foundation: (1) departmental agencies; (2) public law administrations – commonly known as statutory bodies; and (3) private law bodies – commonly known as state owned enterprises (Laking, 2005) [11]. In another perspective, PSOs can also be classified based on their ownership and control. This is particularly beneficial for PSOs in the “private law bodies” class, given their magnitude and potential for being at multiple arm’s length from the core of government. Gomez et al., (2018) for example show that in 2013, the Ministry of Finance controls an estimated 6,342 companies, ten levels down through majority ownership of 35 companies. When considering all types of public organisations then, an expanded view for modern governments is instructive; one of governments being multi-actor and broad enough to capture the extent of ownership and control, extending even into the private markets [12]. The true span of governments is consequently more fully accounted for, properly reflecting realities in the policy arena where agencies at arm’s length from the core of government are often used to implement policy and benefit from fiscal privileges owing to the public purse (World Bank, 2023). Seen within this extended view of governments, the reach of PSOs in their spending, hiring and scope is striking. This is particularly acute for PSOs at multiple arm’s length from the core of government such that the path of monitoring and accountability is also stretched. The Public Accounts Committee (PAC) for example found that Universiti Teknologi Mara (UiTM), a statutory body of the Ministry of Higher Education (MoHE) failed to obtain appropriate approval for RM259.98 million in capital

injection into a holding company, UiTM Holdings. UiTM Holdings in turn, went on to own 14 subsidiaries in 4 business segments with sub-par financial performance. The PAC further heard that representation by MoHE on UiTM Holding’s boardof directors was absent, in part due to the already stretched capacity in MoHE (PAC, 2024). Indeed, modern governments being multi-actor also tends them towards being big, bloated and bureaucratic.

Conclusion

The architecture of modern governments presented above surfaces a seemingly disconcerting proposition; that modern governments, by design, will tend towards becoming big, bloated and bureaucratic. To the extent that this is correct, efforts to make governments small, lean and nimble are akin forming a government that is out of character, i.e. one that only addresses simple problems, one that is organised in a single level of jurisdiction, and one served by public organisations functioning as homogenous entities. Rather, a counter perspective is proposed, one where modern governments exploit their being big, bloated and bureaucratic to their benefit. Governments can be re-imagined as being catalytic, capable and consistent instead. These spend resources in a catalytic manner owing to the potential size of government budgets, shore up deep and broad capabilities owing to their tendency to hire more freely, and minimise uncertainties in service delivery owing to bureaucratic inertia against change. It is a path worth considering—from 3B, to 3C. From Big, Bloated and Bureaucratic to Catalytic, Capable and Consistent.

Footnotes

[1] Fiscal Outlook and Federal Government Revenue Estimates. (2023). Ministry of Finance. [2] Yeap, C. (2019). Cover Story: Can the civil service be downsized? The Edge Malaysia. [3] Kaufmann, et al., (2010). “The Worldwide Governance Indicators”. World Bank Group. [4] Rittel and Webber (1973) identify 10 characteristics of wicked problems: (1) no definitive formulation; (2) no stopping rule; (3) no true-or-false solutions, only good-or-bad ones; (4) no way to test solutions; (5) no opportunity to learn by trial-and-error; (6) unlimited number of solutions; (7) each problem is unique; (8) each problem can be described as the symptom of other problems; (9) solution choice is contingent on problem framing; and (10) solution provider has “no right to be wrong”. [5] Framing refers to the way a problem is organised, understood and articulated. [6] “Actor” here refers to participants within the policy arena of a specific wicked problem. [7] Funds for the Light Rail Transit is reported to be raised through proceeds from the Penang South Island (PSI) project. Post-2023 elections however, the aligned allegiance between the State and Federal Government has seen federal funds being approved for the LRT project which in turn has prompted the Penang State Government to reduce the scope of the PSR project. [8] Public transport is under the purview of the Federal Government while water supply is under the purview of the State Government. [9] Trisha, N. (2023). Penang announces 49% scale-down of PSI project. The Star. [10] Abdullah, S. (2024). Water woes still affecting Kelantan despite large federal govt allocations, says group. New Straits Times. [11] Table 1 in appendix provides a summary of attributes for each class as proposed by Laking (2005) [12] The definition of what State Owned Enterprises have been a matter of debate with no commonly accepted definition. IMF’s Fiscal Monitor for example considers the ownership of at least 50 percent equity, and in some cases, 20 percent (IMF, 2020). The World Bank in its report The Business of the State on the other hand proposes an expanded coverage considering equity ownership of at least 10 percent, whether owned directly or indirectly (World Bank, 2023).Bibliography

Bakvis, H. (2021). Federalism and Multilevel Governance: Contexts for Public Administration. In Handbook of Public Administration (4th ed.).

Routledge.

Conklin, J. (2005). Dialogue Mapping: Building Shared Understanding of Wicked Problem (1st edition). Wiley.

Gomez, E. T., Padmanabhan, T., Kamaruddin, N., Bhalla, S., & Fisal, F. (2018). Minister of Finance Incorporated. Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4897-5

Head, B. W. (2022). Wicked Problems in Public Policy: Understanding and Responding to Complex Challenges. Springer International Publishing. https: //doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94580-0 Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2003). Unraveling the Central State, but How? Types of Multi-level Governance. American Political Science Review, 97(2), 233–243. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055403000649

Laking, R. (2005). Agencies: Their Benefits and Risks. OECD Journal on Budgeting, 4(4), 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1787/budget-v4-art19-en

Mazzucato, M. (2013). The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths (1st edition). ANTHEM PRESS. Osborne, S. P. (2009). Introduction The (New) Public Governance: A suitable case for treatment? In The New Public Governance? Routledge.

PAC. (2024). Laporan Jawatankuasa Kira-kira Wang Negara: UiTM Holdings Sdn. Bhd. Di bawah Universiti Teknologi Mara dan Kementerian Pendidikan Tinggi (DR.3 Tahun 2024). Public Accounts Committee.

Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169.

Robert, K., Smita,Coste,Antoine,Ting,Kok Onn,Leng,Kristina Fong Siew,Maluda,Alyssia Thien Nga,Todd,Laurence. (2022, October). Digitalizing SMEs to Boost Competitiveness [Text/HTML]. World Bank. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099515009292224182/P17608901a9db608

909f5b02980d48c4e28

World Bank. (2023). The Business of the State. The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-19 98-8

Appendix

Table 1: Classification of agency types prescribed by Laking (2005)