Executive Summary

- Malaysia’s private higher education sector has expanded significantly since the 1990s. However, it faces systemic challenges, including a market-reliant regulatory authority, an oversupply of institutions, and financial sustainability issues.

- The large number of private higher education institutions (PHEI) has led to inefficient resource allocation, with excessive market competition straining financial resources, making it difficult for them to improve or even maintain the quality of education.

- Over-education and skill mismatches have left graduates struggling to secure employment, highlighting the need for better alignment between academic programmes and industry demands.

- The Ministry of Higher Education should lead a structured merger and acquisition (M&A) strategy to strengthen PHEI, improve resource efficiency, and enhance academic reputation.

- The government should allocate sufficient funding to the Malaysian Qualifications Agency (MQA) to ensure independent and high-standard academic quality regulation.

Introduction

Discussions on the quality of higher education in Malaysia should not ignore Private Higher Education Institutions (PHEI). Major criticisms of higher education surround the obsession with world rankings and how this affects scientific publications by local public universities to the point of research output being manipulated through ‘creative plagiarism’ (S. Munirah Alatas 2023 & 2024).

For the private sector, financial distress is a key concern (Williams 2024). A common issue for both public and private institutions is skill-related underemployment, where graduates are overqualified and end up in jobs that expect lower qualifications (Hawati Abdul Hamid et al. 2024). Scholars and observers have highlighted many dimensions and layers in the higher education crisis.

This paper focuses on issues affecting the academic quality of PHEI and argue that the sector requires a more structural revamp. Firstly, it will recap a brief history of the development of private higher education since the 1970s. Then, three major systemic issues are highlighted.

Subsequently, we propose recommendations for policy consideration as a way to consolidate private higher education and serve as a preemptive measure for potential crises.

Brief History of Private Higher Education in Malaysia

The development of private higher education has been directly related to the implementation of the quota system in public universities under the New Economic Policy. In the 1970s, the demand for pre-university courses was met by private institutions for students intending to study overseas.

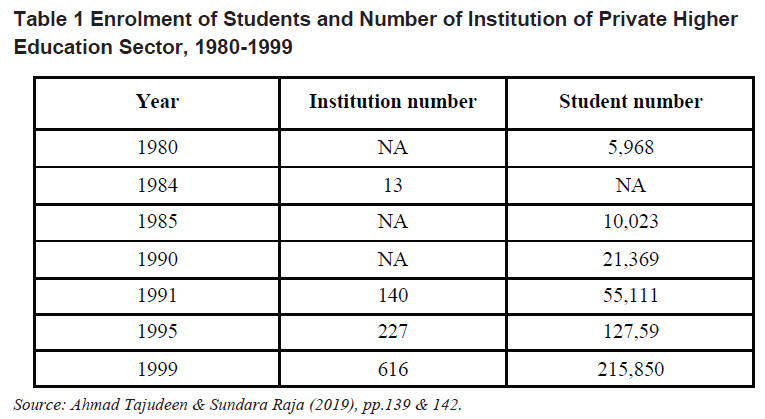

However, the opportunity to study in Western countries was not available to the majority of non-Bumiputera students. In the 1980s, private educational institutions began offering diploma courses and degree-level programmes through twinning arrangements. The total number of students in PHEI tripled from 1980 to 1990 (see Table 1). However, this accounted for only about 8.9% of the total number in the higher education sector (Ahmad Tajudeen & Sundara Raja, 2019: 139).

The private higher education sector gained significant momentum after the liberalization of education policy in the 1990s, which was aimed at making Malaysia a hub for higher education. PHEI were allowed to offer various academic courses, from degree to doctorate level. Economic growth from1993 to 1995 further strengthened the sector through the corporatization of higher education and the involvement of the private sector (Ahmad Tajudeen & Sundara Raja, 2019: 140). The National Council on Higher Education Act 1996 was established to regulate higher education. In 1984, there were only 13 such institutions, but the number grew to 140 in 1991, 227 in 1995, and 616 in 1999

(ibid. 139; see Table 1).

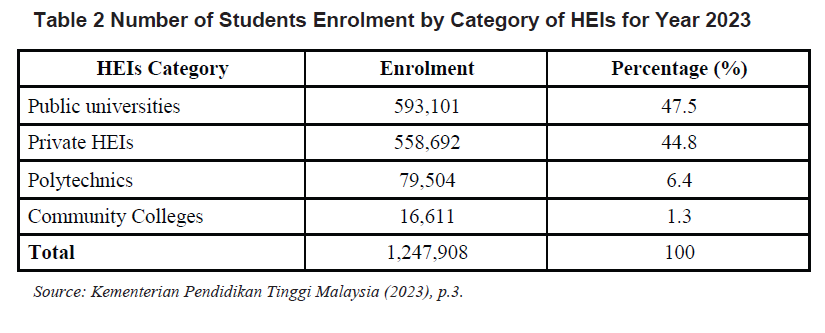

Generous loans for all eligible students provided by the National Higher Education Fund Corporation (PTPTN) have played an important role in financing post-secondary studies as well as contributing to the proliferation of PHEI. By 2023, 558,692 students were enrolled in PHEI, accounting for 44.8% of the total enrolment in higher education institutions (see Table 2). This sector is as equally important as public higher education institutions.

The Systemic Weakness of the Private Higher Education Sector in Malaysia

Private higher education plays a crucial role in Malaysia’s education landscape, complementing public institutions in expanding access to education opportunities. Over the years, this sector has evolved in response to changing economic demands, social advancements, and parent’s expectations.

However, three main challenges are systemic in nature and have a long-term impact on the country’s academic and professional talent development ecosystem.

i) Entrenched Financial Relationship between the Regulatory Authority and Educational Institutions

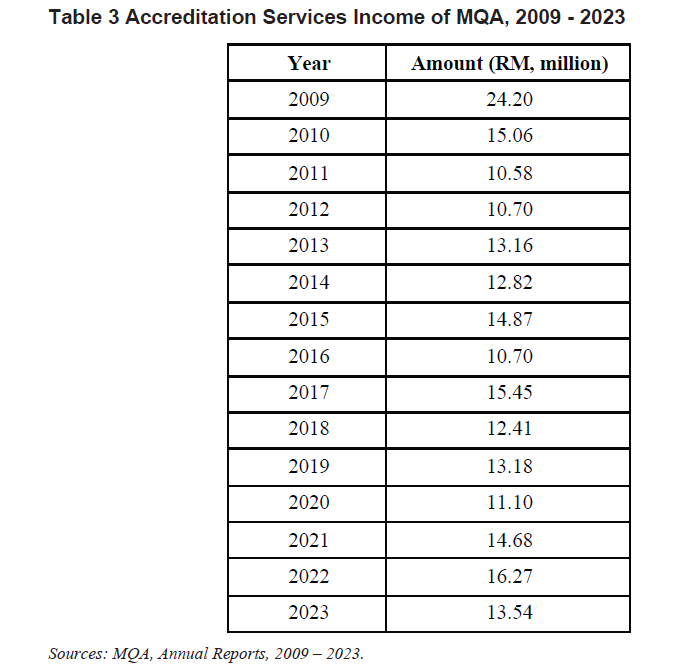

The Malaysian Qualifications Agency (MQA), established in 2007, is a statutory body responsible for facilitating the accreditation of academic programmes for post-secondary and higher education. In 2009, the programme application and accreditation fees collected amounted to RM24.19 million (MQA 2009: 7). The agency has consistently generated more than RM10 million annually through various accreditation services (see Table 3). As an authority body, it partially relies on the expansion of the higher education sector. While government funding supports the MQA, its self-generated income has become an important financial inflow to sustain the agency. An increase in programme applications and approvals boosts its income and ensures its survival. An authority body operating within such a framework leaves it heavily influenced by market dynamics, primarily due to its reliance on fee for funding and operations. The reliance on fees may lead to a conflict of interest, where the authority must balance regulatory responsibilities with the need to maintain revenue stream, ultimately limiting its ability to act independently and effectively in the public interest. The authority may find itself caught in a cycle where market pressures dictate its

actions, potentially compromising its regulatory effectiveness and diminishing its role as a neutral overseer.

There is no available data on the approval rate of programme applications from 2009 to 2022. Data on programme applications and accreditation released during this period focused on the completion of the process within a specific timeframe. The approval rate was only published in 2023. In that year, there were 276 accreditation applications, with 84 new programmes applying for provisional accreditation and 192 programmes applying for full accreditation. A total of 70 programmes received provisional accreditation (83.3% approval rate), while 171 programs (89.1% approval rate) obtained full accreditation (MQA 2023: 99).

ii) Oversupply of Institutions and Unsustainable Competition

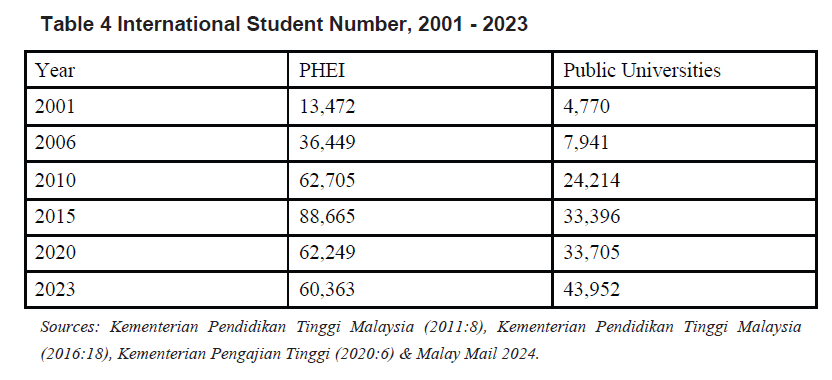

There is an issue of oversupply of institutions in Malaysia. The current ratio of 13 private higher education institutions per million population is high compared to other countries in the Asia-Pacific region, such as Singapore and Taiwan, which have a ratio of 5 per million population (Tan & Cheong 2020: 2). Malaysia’s ambition to become a global hub for private higher education has seen slow progress (see Table 4). In 2023, there were only 104,315 international students, with 43,952 enrolled in public universities and 60,363 in private universities (Malay Mail 2024). This number is statistically insignificant compared to the high number of PHEI, as most institutions struggle to attract international students due to their low reputation and academic quality. The long-standing goal of reaching 250,000 international students has never been achieved. Given the competitive nature of

global university rankings, attracting more international students is more feasible if the main driver is public universities with strong rankings, compared to the private higher education sector, where only a handful of institutions have begun participating and are listed in major global university rankings.

However, this can only be achieved if more resources are allocated to public universities.

The issue of oversupply of institutions leads to market competition that does not result in efficiency but instead creates a financial sustainability crisis for weaker institutions. The total market value of the private higher education sector in 2024 was estimated at RM17 billion (Tan & Cheong 2020: 2).

However, excessive marketing costs have affected the quality of academic services. To compete and build brand recognition in a competitive market, PHEI have allocated significant resources to marketing activities. The financial and human resources deployed for marketing are considered equally as important as those dedicated to academic operations. There are no clear data on the ratio of PHEI investment in academic development relative to marketing expenditure. However, it is common for education institutions to spend up to 10% to 20% or even higher of their revenue on marketing activities. The intense competition among PHEI in Malaysia has resulted in resource wastage rather than market efficiency with improved academic quality.

After the pandemic, news of the financial crisis in PHEI has gained media attention (Malaysiakini 2024). With Malaysia facing a low birth rate and an aging demographic in the coming years, coupled with an academic reputation that is below par for attracting international students, sustainability distress among PHEI is looming, similar to the situation currently unfolding in Taiwan. Private universities in Taiwan have been closing down since 2014 due to the low birth rate, and it is estimated that 40 out of 103 private higher education institutions may close by 2028, with the number rising to 50 by 2038 (Lee 2024).

iii) Sustainability Challenge of PTPTN Loan

By the end of 2024, PTPTN had approved 3,951,404 loans totaling RM71 billion, but over 2.7 million loans remained unpaid, with 420,000 borrowers not making a single payment (Nadeswaran 2024). Besides a culture of entitlement and an execution inefficiency in the bureaucracy, the issue of non-payment is also linked to over-education, where graduates do not receive adequate compensation for their qualifications. Over-education in this context has two dimensions. Firstly, current PHEI predominantly offer only conventional academic streams that are not suitable for learners with different abilities. Parents’ academic expectations have led to students enrolling in standard academic training, often barely meeting the minimum passing requirements. As a result, these graduates face poor employment prospects or low workplace performance. The second dimension is the skills

mismatch, where graduates accept jobs that do not align with their qualifications and fields of study, or resort to non-standard work (Hawati Abdul Hamid et al. 2024).

Many PHEI rely on PTPTN to recruit students. To reduce the financial burden on students, PHEI employ several strategies for tuition fee payments. The fee structure for each semester is often designed to align with the reimbursement of PTPTN loans. Some colleges also set their fees within the total amount of PTPTN loans that students are eligible for. The sustainability of PTPTN not only affects students but also impacts the survival of private institutions.

Recommendations

1. Rationalization of institution supply through mergers and acquisitions

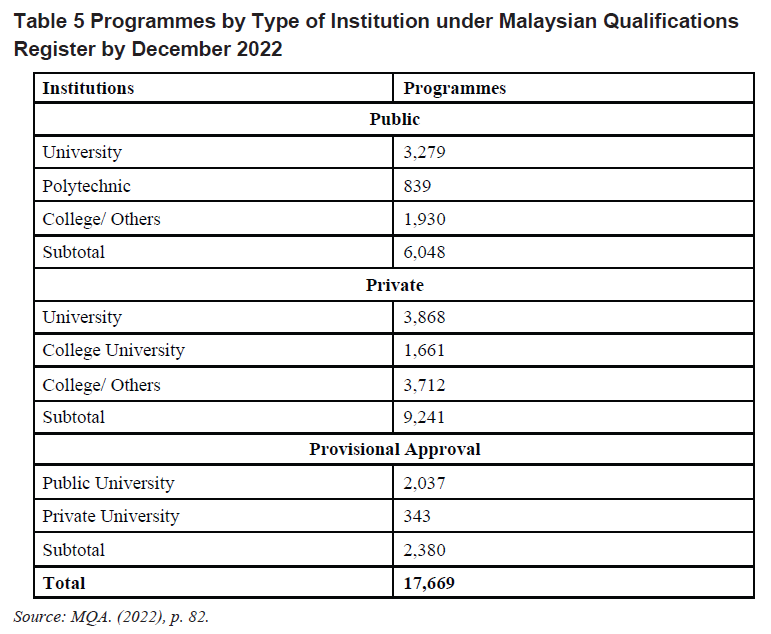

The private higher education sector has prospered since the 1990s under the liberalization of higher education policy. There are more academic programs offered by PHEI compared to public institutions. In 2022, PHEI offered approximately 9,241 programmes, while public institutions offered 6,048 programmes (see Table 5). The total number of institutions once peaked at 616 in 1999.

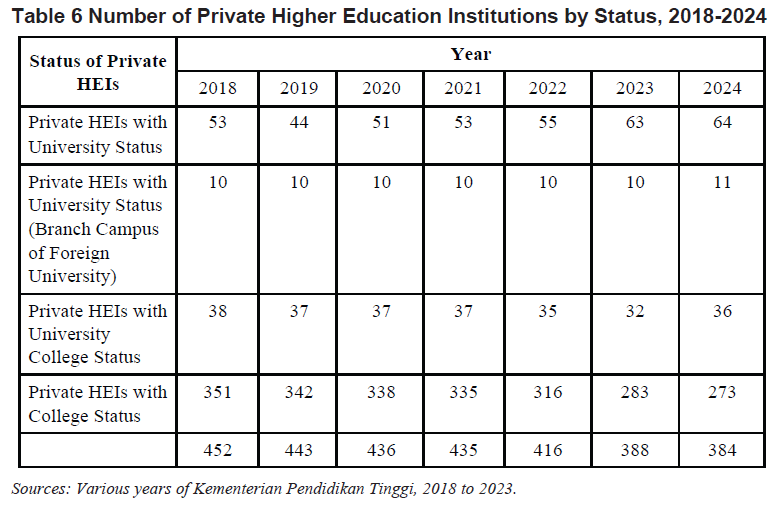

However, authorities have taken stricter actions to gradually close down a significant number of institutions that failed to meet basic requirements. As a result, the number of institutions has decreased from 452 in 2018 to 384 in 2024 (see Table 6). The issue now is whether these institutions are the suitable number for the age of AI, with its revolutionary nature of knowledge transmission, amid an aging population and an increasingly competitive global higher education market. Is the future failure of these institutions inevitable?

There is a need to further rationalize the total number of institutions to consolidate the private higher education sector through mergers and acquisitions (M&A). Ideally, there should be a limited number of strong institutions with a good reputation at the national or even regional level. The M&A approach should encourage strong institutions to acquire weaker entities and streamline academic programmes for better market efficiency. Currently, there is a significant overlap in academic offerings across PHEI. Many institutions continue to run classes despite low student enrollment, leading to a waste of resources and a less-than-ideal learning experience for students.

The Ministry of Higher Education should plan and guide a far-reaching M&A process to uplift current PHEI and prevent a future survival crisis. This pre-emptive measure aims to strengthen the private higher education sector. Naturally occurring, market-driven mergers may not be able to address the need for transformation in a timely manner, as current industry players are more focused on surviving market competition than being forward-looking; they often lack financial resources as well. A mid-range country with a high density of higher education institutions is a ticking time bomb for the sector, especially at this critical juncture of technological change and knowledge production, which will reshape the way and philosophy of higher education learning.

2. Protect MQA from market forces through full funding

As the academic quality gatekeeper, MQA should receive full financial support from public funds to carry out its duties as the authority body without concerns over operational costs. According to annual reports, the additional funding required yearly is around RM20 million or less, for MQA to be fully funded without relying on income generation through various programme accreditation and approval fees. This additional public funding of RM20 million is reasonable, or even relatively low, considering MQA’s crucial role in ensuring the = academic quality of the higher education sector.

Conclusion

The open policy of the private higher education sector since the 1990s has been progressive,

contributing to the nation’s human capital development and the self-fulfillment of younger

generations across different socioeconomic groups and ethnicities. However, the market-driven competition in the private higher education sector has always created tension between quality of education and profit. In recent years, the sector has faced intensified price competition amid a declining birth rate in Malaysia and sluggish international student enrollment.

Mergers and acquisitions should be encouraged through an authority-driven policy to ensure fair competition while maintaining the vibrancy of the sector. Ideally, larger education groups should take the lead in reducing the total number of PHEI to a reasonable figure, providing equally high-quality education specialized in distinctive disciplines. This rationalization process will enable better resource sharing in terms of teaching staff and state-of-the-art facilities. It should achieve market efficiency and prevent unhealthy competition that could undermine academic quality and students’ interests.

The private higher education sector in Malaysia has a decades-long history of support from leading industry leaders across various backgrounds. Both financial and expertise support from the industry are crucial in cultivating great institutions of learning. With the rapid changes brought by technological advancements, higher education must adapt to meet the market demand for labour training. Achieving the first phase of mergers and acquisitions will allow the sector to thrive by reducing unnecessary competition. It will also ensure the sector’s survival in the face of aging society, global competition, and the ongoing AI transformation in knowledge production, distribution, and training.

References

- Ahmad Tajudeen, Aishah Bee & Sundara Raja, Sivachandralingam. (2019). “Perkembangan Institusi Pengajian Tinggi Swasta (IPTS) di Malaysia, 1957-2010”. Sejarah, 28 (1): 133-152.

- Hawati Abdul Hamid et al. (2024). Shifting Tides: Charting Career Progression of Malaysia’s Skilled Talents. Kuala Lumpur: Khazanah Research Institute.

- Kementerian Pendidikan Tinggi Malaysia. (2011). Indikator Pengajian Tinggi 2009 – 2010. Link, accessed 27 February 2025.

- Kementerian Pendidikan Tinggi Malaysia. (2016). Makro – Institusi Pendidikan Tinggi 2015. Link, accessed 27 February 2025.

- Kementerian Pendidikan Tinggi Malaysia. (2018). Statistik Pendidikan Tinggi 2018. Link, accessed 27 February 2025.

- Kementerian Pendidikan Tinggi Malaysia. (2019). Statistik Pendidikan Tinggi 2019. Link, accessed 27 February 2025.

- Kementerian Pengajian Tinggi. (2020). Statistik Pendidikan Tinggi 2020. Link, accessed 27 February 2025.

- Kementerian Pengajian Tinggi. (2021). Statistik Pendidikan Tinggi 2021. Link, accessed 27 February 2025.

- Kementerian Pengajian Tinggi. (2022). Statistik Pendidikan Tinggi 2022. Link, accessed 27 February 2025.

- Kementerian Pendidikan Tinggi. (2023). “Chapter 3: Private Higher Education Institutions” in Statistik Pendidikan Tinggi 2023. Link, accessed 27 February 2025.

- Lee, Elaine. (2024). “Four universities in Taiwan to close due to dip in enrolment”. The Straits Times, 7 June 2024. Link, accessed 10 February 2025.

- Malay Mail. (2024). “Zambry: Target for 250,000 international students in Malaysia includes both public and private institutions”. Malay Mail, 18 October 2024. Link, accessed 10 February 2025.

- Malaysiakini. (2024). “Ministry probes private university over unpaid wages”. Malaysiakini, 7 June 2024. Link, accessed 10 February 2025.

- MQA. (2009–2023). Laporan Tahunan (various years). Kementerian Pendidikan Tinggi. Multiple reports accessible via this link, accessed 8 February 2025.

- Nadeswaran, R. (2024). “COMMENT | The correlation between defaulting on PTPTN loans and graft”. Malaysiakini, 20 December 2024. Link, accessed 7 February 2025.

- S. Munirah Alatas. (2023). “Alternatives to global university rankings”. The Free Malaysia, 18 December 2023. Link, accessed 6 February 2025.

- S. Munirah Alatas. (2024). “Here’s how we tackle ‘creative plagiarism’ in academia”. The Free Malaysia, 3 February 2024. Link, accessed 6 February 2025.

- Tan, Yennie & Cheong, Yen Li. (2020). “Harnessing Education in the New Economy: Private Higher Education Investments in Malaysia”. PwC, May 2022. Link, accessed 10 February 2025.

- Williams, Geoffrey. (2024). “The main challenges for higher education reform”. The Free Malaysia, 19 July 2024. Link, accessed 6 February 2025.

You might also like:

![Covid-19 Fuels Democratic Decline in Southeast Asia]()

Covid-19 Fuels Democratic Decline in Southeast Asia

![Sustainable Strategies based on Penang Infrastructure Corporation's Projects]()

Sustainable Strategies based on Penang Infrastructure Corporation's Projects

![Policymaking and Implementation: Shifting from Hierarchies to Interdependent Polycentric Networks]()

Policymaking and Implementation: Shifting from Hierarchies to Interdependent Polycentric Networks

![Logging in Ulu Muda Forest Reserve: Is Penang’s Water Security under Threat?]()

Logging in Ulu Muda Forest Reserve: Is Penang’s Water Security under Threat?

![Reducing Moral Hazards in Malaysia’s Public Healthcare System]()

Reducing Moral Hazards in Malaysia’s Public Healthcare System