By Ong Wooi Leng (Head of Socioeconomics and Statistics Programme)

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- There is a growing number of city-level global financial centres, especially in Asia, playing supporting roles to national economic growth.

- The success of global financial centres are increasingly tied to specialisation and leveraging existing industrial strengths, as demonstrated by established hubs such as Hong Kong and Singapore and emerging ones like Busan (maritime/blockchain finance) and Shenzhen (venture capital/tech finance).

- Penang possesses a strong economic foundation, with a mature ecosystem of financial and business services supporting its world-class E&E manufacturing sector. However, over-reliance on this single sector without strong capital innovation in local industries creates economic vulnerability, a situation underscored by a stark disparity in GDP per capita with a former peer, namely Busan.

- The successful models of Busan and Shenzhen provide a blueprint that highlights the necessity of strategic state support, regulatory innovation (e.g., sandboxes), and policies that foster high-value industries like fintech, wealth management, and green finance.

- A strategic way forward requires a dual focus: firstly, on promoting high regulatory and legal standards to build trust, and secondly, on proactively fostering niche financial services that reinforce Penang’s existing industrial strengths.

1. Introduction

Global financial centres have historically emerged on robust industrial and economic foundations, where financial services act as intermediaries crucial to the deepening of technological competitiveness and for accelerating economic growth. In the contemporary era, technological innovation itself has become a primary driver of financial centre development (Phung et al., 2003). This nexus of finance and technology underpins the potential held by Penang – historically renowned as Asian’s Silicon Island – to evolve into a leading financial and commercial hub, a vision once publicised by Tun Dr Lim Chong Eu, when he was Chief Minister of Penang (Todd, 1986).

While the core finance activities remain essential and concentrated in the Klang Valley, which accounted for 60.6% of Malaysia’s GDP in 2024, the Labuan International Business and Financial Centre (IBFC), which offers cross-border financial transactions, business dealings, risk management, insurance, and wealth management, contributed 2.6% of the national GDP. Meanwhile, in the northern region of Malaysia, the finance, insurance, real estate, and business services sector accounts for 11.7% of the sector’s GDP. Presently, the region boasts a mature presence of local and international firms serving the local and global community, as well as multinational manufacturing and services industries in Penang and the northern region. These services include:

- Retail, business and corporate banking (trade financing, credit facilities and treasury management);

- Global business services (finance and accounting, IT services, human resources, supply chain management and research);

- Investment and wealth management (unit trusts, mutual funds, financial planning and advisory services, stockbroking and securities trading);

- Insurance and Takaful; and

- Professional services (consulting, trading and legal).

This paper examines the performance of top financial centres worldwide and explores the development of global and emerging financial centres, with a specific focus on the Asia-Pacific region.

2. Top Financial Centres in Asia Pacific

The Z/Yen Group’s Global Financial Centres Index 36 (GFCI) analyses the competitiveness and ranking of 133 financial centres worldwide, including 12 associate centres (with Labuan classified in the latter group).[1] New York and London are the top global financial centres with deep domestic markets. In the Asia-Pacific region, Hong Kong and Singapore are the leaders, followed by Shanghai, Shenzhen and Seoul.

Table 1 shows that seven of the world’s top 20 financial centres are located in Asia, predominantly in China and Singapore. While Kuala Lumpur has yet to achieve a top-tier ranking, it has demonstrated significant progress, climbing more than 10 places in the GFCI to position 59 in 2024, surpassing cities like Stockholm (66), Hangzhou (72), and Taipei (73).

Table 1: The top ten global financial centres, September 2024

Not with standing that New York and London are global leaders in banking, finance, insurance, trading, fintech, professional services, government and regulatory affairs, Hong Kong thrives as the world’s premier financial centre in investment management. It is home to for an international private wealth management centre that managed USD 4,558 billion in assets as of 2021.[2]

Hong Kong is also the first in the world to fund initial public offerings (IPOs) and arrange international Asian bond issuance. Its strengths include an excellent financial infrastructure, a transparent regulatory and legal system, and being a gateway to China, along with an established financial market and an abundance of skilled professionals.

While Hong Kong is the central safe-haven and global wealth hub in Asia, Singapore is emerging as one of Asia’s principal hub for family offices that manage the wealth of ultra-rich families. The number of single-family offices (SFOs) there increased significantly to 2,000 in 2024 from just 400 SFOs in 2020, partly attributable to its tax incentives and the city-state’s pro-business and well-regulated environment.[3]

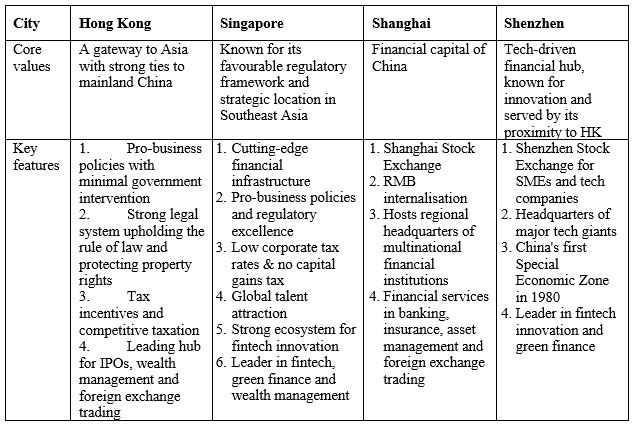

However, Singapore trails New York in professional services, government and regulatory, fintech, and financial trade. The city-state prospers particularly regarding forex turnover by country, the size of ultra-rich residents [4], financial secrecy, and fintech, as well as having a competitive corporate tax rate of 17% [5](compared to the US’s 21% and Malaysia’s 24%). Table 2 summarises the core values and features of the top four global financial centres in Asia.

Table 2: Key characteristics of top global financial centres in Asia, 2024

3. Case studies: Emerging financial centres in the Asia Pacific

Global financial centres have become increasingly regionalised over the last two decades. Traditional leading financial hubs are no longer a nation’s sole centres for financial activity. Geopolitical and economic disruptions have prompted countries to diversify their financial services by establishing specialised centres in second-tier cities. These are designed to channel capital directly into a city’s key sectors, and drive national economic growth.

Busan International Finance Centre – A Marine Financial City

Busan, the second-largest city in South Korea, established the Busan International Financial Centre (BIFC) in 2009. The centre is now among the top 10 global financial centres in Asia, ranking just behind Beijing and Tokyo (Z/Yen, 2024a). While Seoul remains the national financial hub for South Korea, Busan focuses on maritime finance, derivatives, financial digital and technology. As the world’s fifth busiest port, it serves as a critical maritime logistics hub for international trade and shipping in Northeast Asia (Yeandle, 2014). South Korea capitalises on Busan’s capabilities in port logistics and shipbuilding; the city has over a short time established itself as a strategic Marine Financial City.

The financial hub aims to strengthen the maritime economy, encompassing related activities such as the fishing industries (i.e., commercial fishing and aquaculture), marine and ocean research and sciences, maritime training academies and training centres, as well as the cruise and recreational sectors. Marine finance roped in the commercial activities of the marine industry such as financing ship acquisitions, developing/repairing technology, ship broking, container box leasing, marine insurance and legal payments. Marine investments, on the other hand, involve sale-leaseback transactions, direct equity in shipping companies or joint ventures for ship acquisitions and management (Yeandle, 2014; Z/Yen, 2024b).

The Busan Finance Centre (BFC) was established through joint efforts between the city of Busan and seven local financial institutions and companies. The aim has been to promote Busan as a financial hub and bolster the financial industry in Busan (Z/Yen, 2024b). BFC develops and implements strategies to attract financial institutions and create a financial ecosystem, and conducts mid-to-long-term finance-related surveys and research into Busan’s development, and facilitates internal and external cooperation.

Busan continues to evolve. It is transforming from being a city-level financial centre into a blockchain industry zone. In 2019, the metropolitan city was designated as the only national blockchain regulation-free special zone in South Korea. The Busan Blockchain Regulation Free Special Zone enables commercial businesses operating in the city to apply for a regulatory sandbox specialising in blockchain technology applications to conduct tests for innovative technologies without restrictions. Additionally, innovative firms are supported by measures such as R&D funding and tax breaks. To create a Busan FinTech Hub, BIFC also provides FinTech and blockchain incubation facilities to support tech and blockchain startups.

Based on the Busan blockchain regulatory sandbox, approvals have been granted for commercial services on the blockchain-based Smart Marine Logistics platform, the Busan Smart Tour platform service, the medical data platform, the ledger-based local economy revitalisation service, and others. Another notable business participating in its financial regulatory sandbox is a real-estate Security Token Offering (STO) platform; this platform enables retail investors to invest in selected properties earning fractional ownerships.

To build Busan city as a global digital finance and blockchain hub, the Busan Digital Asset Nexus (BDAN) has been established, and is the first exchange led by local governments with 100% private capital, and is also a “4th generation blockchain-based decentralised digital asset exchange” in South Korea (The Block, 2025). As a blockchain developer and enabler, BDAN is expected to create a regulated and transparent market for various types of tokenised assets (Yoon, 2024).

On 25 January 2024, South Korea further designated Busan a Global Hub City supported by a Special Act to establish the Financial Opportunity Development Zone (ODZ). In efforts to further reinforce the maritime financial city, this zone envisions facilitating the creation of a global finance hub, a tri-port logistics hub and technology-driven industrial ecosystems. On the sustainable development aspect, Busan city is to establish itself as a sustainable maritime finance hub. There is funding available for eco-friendly ships and a sustainable infrastructure ecosystem supporting maritime net-zero transition through the Green Ocean Fund, green bonds and ESG bonds.

Shenzhen Financial Centre – A Hub for Venture Capital and High-Tech Finance

Shenzhen—often referred to as China’s “Silicon Valley”—leverages its proximity to Hong Kong and has established specialised financial services for high-growth and innovative enterprises within China’s financial framework. Despite the fact that Hong Kong and Shanghai remain the primary financial centres in China’s economy, Beijing and Shenzhen perform unique functions and roles that have collectively driven the rapid growth of both Chinese and Asian economies (Xiaobin, et al., 2013). Shenzhen has risen to become a hub for venture capital (VC) and private wealth management, in addition to serving as a key testing ground for financial reforms and cross-border cooperation with Hong Kong.

As China’s largest VC hub, Shenzhen is home to numerous funds that support high-tech startups and emerging enterprises. A key focus for the city is developing its VC market and establishing dedicated growth enterprise boards on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE), namely the ChiNext board and the SME Board.

The ChiNext board is China’s NASDAQ-style stock market enabling high-growth technology companies that do not meet the listing requirements of the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) to raise funds from the public market. The initiative has made the ChiNext board the world’s third-largest market for growth enterprises, attributed to its strategic location and its crucial role in financial innovation experiments within China.

Additionally, Shenzhen’s position has been further strengthened by the establishment of the Financial Innovation Zone, which is designed as an experimental hub to leverage its proximity to Hong Kong and take advantage of preferential policies. This has strengthened the city’s fund industry, allowing it to emerge as a private wealth management centre in collaboration with Hong Kong.

Furthermore, in 2009, the Qianhai Shenzhen-Hong Kong Modern Service Industry Cooperation Zone was developed to promote financial sector reform through enhanced cooperation (Xiaobin et al., 2013). This initiative has fostered cross-departmental collaboration and has been crucial in boosting China’s financial strength while supporting Shenzhen’s booming technology sector.[6]

While Shanghai remains the epicentre of China’s economic powerhouse and a global hub for international trade and commerce, Beijing functions as the financial policy-making centre (Zhao, 2003).[7] The national capital houses the headquarters of major regulatory bodies and state-owned enterprises, including policy banks, commercial banks, and regional banks. This makes it a popular place for major financial institutions to base their head offices, while maintaining their main operating bases elsewhere in the country.

Historically, Shenzhen became China’s first special economic zone (SEZ) in 1980, offering special financial, investment, and trade privileges (Zeng, 2010). Its economic progression resembles that of Penang, but growing at a much faster pace, fuelled by strong government policies and significant foreign direct investment. [8] It houses world-class technology companies and brands, such as Huawei, Tencent, WeChat, and BYD. it was just a traditional fishing village 50 years ago. Over the past 30 years, secondary and high-tech services industries have emerged as the primary sources of Shenzhen’s economic growth. The city achieved Penang’s present standard of living 15 years ago.

Lessons Learnt from Emerging Global Financial Hubs: The Way Forward for Penang

Emerging financial centres are increasingly concentrated in high-growth regions and strategic locations, such as free trade zones or areas of primary economic activity. Designed to boost a city’s output, employment, and income, such a centre serves as a catalyst for national growth. It functions as a specialised hub to diversify the economy and promote balanced regional development. While having high regulatory and legal standards is crucial for a financial centre, it is equally beneficial for developing the industries that already thrive within the cities.

Critically, the transformative success of centres like Shenzhen and Busan offers a vital blueprint, demonstrating how strategic state support for innovation, education, and high-value industries can catapult a regional economy onto the global stage.

A comparison with South Korea’s development reveals significant potential for improvement for cities in Malaysia. For example, Penang – Malaysia’s second-tier metropolis and a hub for diversified and resource-processing manufacturing (Meyer, 1986) – once outperformed Busan economically. In 1970, Penang’s per capita GDP of RM4,739 (USD$1,548) far exceeded South Korea’s national figure of US$279.[9] Today, however, this dynamic has undergone a considerable reversal. Busan’s per capita GDP (USD 33,900) is now twice that of Penang’s (RM 76,033 or USD 17,013 in 2024).[10] This disparity persists despite Penang’s specialisation in E&E manufacturing, underscoring that Busan, with a population of 3.47 million (2023) [11], now boasts a significantly higher standard of living.

Penang’s economic success is primarily anchored in its electrical and electronics (E&E) manufacturing sector, which has attracted significant foreign investment and global business services, resulting in spillover effects to neighbouring states in the region. This specialisation, however, makes the region highly vulnerable to global economic shocks and trade tensions, which can impact income and employment. To mitigate this risk and ensure sustainable long-term growth, there is a pressing need for Penang to diversify its capital investments to support its local E&E ecosystem. This is especially important for local industries, as strong capital innovation is crucial for a regional economy to move onto the global stage.

To this end, Penang has the potential to leverage its established strengths in the E&E sector and its pivotal geographical location in the heart of the Indonesia-Malaysia-Thailand Growth Triangle (IMT-GT) to position itself as a significant regional financial hub. Also, the growing international demand for education, and the Malaysia My Second Home (MM2H) programme provide a variety of opportunities for wealth management and retail banking, among others.

Footnotes

[1] This index, updated every March and September, is a collaboration between Z/Yen and the China Development Institute (CDI). [2] Hong Kong Monetary Authority (2025). Hong Kong as an International Financial Centre. Retrieved from https://www.hkma.gov.hk/eng/key-functions/international-financial-centre/hong-kong-as-an-international-financial-centre/ [3] Wong, C. P. (2025, Jan 14). Singapore family offices exceed 2,000 in 2024, up 43% on year. The Business Times. Retrieved from https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/companies-markets/singapore-family-offices-exceed-2000-2024-43-year [4] According to the 2024 UBS’s Global Wealth Report, 6.5% of Singapore’s adult population are millionaires in 2023. This is equivalent to 333,204 millionaires (inclusive of billionaires). High-net-wealth (HNW) individuals have a net worth between US$1 million and US$50 million while ultra-high-net-worth (UHNW) individuals have more than US$50 million. [5] Filipovski, B. (2023, Jan 3). Singapore – the leading financial centre in the Asia-Pacific region. Capital Finance International. Retrieved from https://cfi.co/asia-pacific/2023/01/singapore-the-leading-financial-centre-in-the-asia-pacific-region/ [6] The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (2023). LCQ1: Qianhai Shenzhen-Hong Kong Modern Service Industry Cooperation Zone. Press Releases. Retrieved from https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202306/21/P2023062100332.html [7] Beijing has the largest bond market in China, with significant issuance of Treasury Bonds and corporate bonds. Treasury bonds are issued by the Ministry of Finance in China, and the People’s Bank of China issues bills/notes, and they are mostly traded on the OTC market. Meanwhile, corporate bonds are issued by 13 joint-stock commercial banks and 100 state-owned companies (Xiaobin et al., 2013). China’s capital city is also a hub for private equity (PE) funds, due to its proximity to policy information and regulatory bodies. Unlike Hong Kong’s position as Asia’s import PE fund centre for capital, Beijing’s main source of funds for PE is from the government. [8] Foreign direct investment made a significant contribution to Shenzhen’s industrialisation. The inflow of foreign capital was largely in the area of manufacturing, followed by real estate and commerce. [9] Macrotrends (n.d.). South Korea GDP per capita. Retrieved from https://www.macrotrends.net/global-metrics/countries/KOR/south-korea/gdp-per-capita [10] Metroverse (n.d.). What is Busan’s economic composition? Harvard Kennedy School. Retrieved from https://metroverse.cid.harvard.edu/city/12678/economic-composition#:~:text=city’s%20economic%20composition%3F-,What%20is%20%E2%81%A8Busan’s%E2%81%A9%20economic%20composition%3F,%E2%81%A9%20highest%20GDP%20per%20capita. [11] Macrotrends (n.d.). Busan, South Korea Metro Area Population (1950-2025). Retrieved from https://www.macrotrends.net/global-metrics/cities/21757/busan/populationReferences

Duc, H. V. and Nhan, T. N. (2021). Determinants of a Global Financial Centre: An Exploratory Analysis. Borsa Istanbul Review, 21-2, 186-196.

International Monetary Fund (IMF, n.d.). Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/Financial-Integrity/amlcft

Meyer, D. R. (1986). System of cities dynamics in newly industrialising nations. Studies in Comparative International Development, 21, 3-22.

Phung, G., Truong, H., and Trinh, H. H. (2023). Determinants in the development of financial centres: evolution around the world. International Finance Review, 337-362.

The Block (2025, May 30). Bdan, Hashed, and Npay Sign Agreement to Develop Web3 Wallet for Busan Citizens. Chainwire. Retrieved from https://www.theblock.co/press-releases/356364

Todd, H. (1986). Penang: Asia’s ‘Silicon Island. Reader’s Digest, March, pp. 17-21.

UBS (2024). Global Wealth Report 2024: Crafted wealth intelligence. Retrieved from https://www.ubs.com/global/en/wealthmanagement/insights/global-wealth-report.html

Xiaobin, Z. S., Qionghua, L., & Ming, C. N. Y. (2013). The rise of China and the development of financial centres in Hong Kong, Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen. Journal of Globalization Studies, 4(1), 32-62.

Yeandle, M. (2014). Maritime Financial Centres. Z/Yen Partners. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3672190

Yoon, Y.-S. (2024, Oct 28). Busan Digital Asset Exchange Launches Official Brand “BDAN”. Business Korea. Retrieved from https://www.businesskorea.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=227972

Z/Yen (2024a). The Global Financial Centres Index 36. September. Long Finance and Financial Centre Futures. Retrieved from https://www.longfinance.net/publications/long-finance-reports/the-global-financial-centres-index-36

Z/Yen (2024b). Focus on Busan 2024. April. Financial Centre Futures. Retrieved from https://www.longfinance.net/publications/long-finance-reports/the-global-financial-centres-index-36

Zeng, D. Z. (2010). Building Engines for Growth and Competitiveness in China: Experience with Special Economic Zones and Industrial Clusters. The World Bank, Directions in Development, Countries and Regions. Retrieved from https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/pt/294021468213279589/pdf/564470PUB0buil10Box349496B01PUBLIC1.pdf