Executive Summary

- Food hawking is an integral part of Penang’s identity. However, its food hawkers are an ageing population, and only 21% of those interviewed in our study have a definitive succession plan

- A preservation policy is needed; and measures undertaken to attract new entrants into the industry

- Suggested measures include:

» Commissioning an in-depth study to assess the future supply trend of food hawkers;

» Enforcing higher premise standards in hawker centres;

» Promoting the national retirement scheme to food hawkers;

» Providing upscale assistance to existing food hawkers;

» Incorporating a module on Penang cuisine into the culinary arts programmes;

» Establishing Penang cuisine entrepreneurship incubators; and

» Reviewing the ban on foreign cooks. - An in-depth assessment is likewise necessary on the sustainability of food hawking in Penang; as is a redesigning of the profession into a viable career choice for the younger generation

Introduction

Food hawking is an integral part of Penang’s identity and contributes significantly to the tourism sector[1] and the local economy in general[2].

The industry is also often perceived as a last-resort career option for the lowly educated and the unemployed. As many as 80% of those working in the informal sector have only SPM qualification and below, according to the 2017 Informal Sector Work Force Survey Report[3].

Cheng (2017) highlighted the difficulty in maintaining the taste and price of hawker food, as well as the ban on foreign cooks as the industry’s main barriers. Surprisingly, the authorities have given little attention to the sustainability of the industry as a whole.

Per contrast, numerous policies including supporting new entrants, promoting service spirit, improving productivity and enhancing hawker centres as social spaces were recommended by Singapore’s Hawker Centre 3.0 Committee[4] to its government in early 2017. The concept of “hawkerpreneurship” was likewise introduced to encourage youths to enter the industry.

To provide a preliminary gauge on the sustainability of Penang’s food hawking industry, face-to-face interviews were conducted in August 2018 with 35 local food hawkers[5] from 23 hawking areas across five districts. The interview results were then refined based on the feedback from three different food hawker associations[6] in Penang.

Reasons for getting into the food hawking industry

Profitability appears to be a major pull factor – cash incomes can be made daily, which is preferable to salaries being received only monthly, and they can be sizeable. As many as 77% of the food hawkers interviewed earn more than Penang’s median household income of RM5,409[7]. This is further complemented by the industry’s low entry barrier. No educational attainment or working experience is needed for someone to get into food hawking.

The freedom enjoyed, mainly of flexible working hours, when managing a food hawking business is also an attractive feature. Other pull factors are a passion for cooking and inheriting the family business.

Reasons for not getting into the food hawking industry

Most food hawkers fiercely reject the idea of their children or grandchildren taking over the family business. This is because of the negative perceptions affixed to the profession, such as low social standing. A demanding work environment, and the repetitive and often laborious day-to-day tasks of food hawking also deter the young from entering the industry; those with an interest in the culinary arts are more inclined to pursue glamorous, non-local forms of cuisine.

Sixty-five percent of the hawkers interviewed operate their businesses at least seven hours daily, and 84% of them are open for business six days a week.[8] However, most food hawkers are still unable to afford a comfortable retirement due to the absence of retirement benefits. As such, many continue working until they are physically no longer able to do so.

The supply of food hawkers in Penang

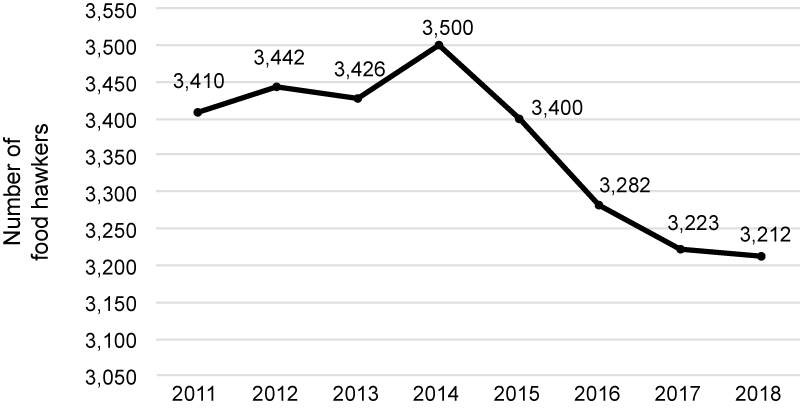

Since 2014, the number of food hawkers in Penang has been on a gradual decline (Figure 1). This is reflected in the fact that only 20% of the respondents have a definitive succession plan in place. Assuming that the average age of a local food hawker is 50 years old, and that they would continue to work until the national retirement age of 60[9], Penang should see a sharp decline in food hawkers within the next 10 years.

Interestingly, the food hawker associations in Penang do not share a cohesive view on the future of the industry. One hawker association observes that a lack of sustained interest from the younger generation will result in a significant drop in its numbers; currently, only two hawker centres are either being operated by youths, or will be succeeded by them. By comparison, the two other associations are confident that the number of food hawkers will remain resilient due to strong demand for Penang food.

Figure 1: The number of new and renewed licenses issued for food hawkers by MBPP

A balancing act in sustaining local food hawking

In preserving Penang’s food hawking heritage, however, different stakeholders have different priorities: local netizens place emphasis on the food’s taste and affordability, while the food hawker associations push for better quality of life for their members. Ironically, the food hawkers themselves pay little attention to the profession’s sustainability and aim instead at being able to

financially provide for their families.

This disparate situation may not be all that significant however, since measures to safeguard certain aspects of the food hawking industry can result in spill-over effects onto other aspects. To balance the needs of different stakeholders, it is recommended that the state government devise an operational preservation strategy.

- Taste: Centuries of cultural assimilation and layer upon layer of culinary innovation by traders and settlers have defined the taste of Penang’s famous cuisine[10]. Preservation of the local food can be approached in two ways: by ensuring the taste remains the same, or by preserving the spirit of culinary innovation.

- Price: Affordability and hawker food go hand-in-hand. But there are hawker stalls that have successfully upscaled into restaurants, resulting in a price hike in the food they offer. Some argue that this is necessary to improve the hawkers’ socioeconomic status, while others contend that it goes against Penang’s heritage of affordable street food.

- Easy availability: Attracting newcomers to maintain the ubiquity of food hawkers in the state is a tall order, and recruiting new hawkers through artificial means may also have a negative impact on the taste and price of the food.

- Socioeconomic background: Food hawking is traditionally pursued by people from the lower socioeconomic stratum, or by those with limited educational attainment. And so, the industry is under noticeable threat as Penang becomes a more broadly educated society.

A proposed preservation strategy

The state government should consider proactive measures for improving the hawkers’ work environment, attracting new entrants into the industry, and elevating the status of the profession. Innovation has been central in shaping and sustaining the local cuisine. Embracing yet another wave of change by a new generation of food hawkers should therefore be encouraged regardless of the necessary price hikes.

Suggested measures to sustain Penang’s food hawking industry

1. Commission an in-depth study to assess the future supply trend of food hawkers

The state government could start by collecting information about hawkers’ succession plans as part of the license renewal process for a more accurate assessment of the industry’s sustainability.

A study on “how to redesign and rebrand the food hawking industry as a career for the younger generation” could also be conducted by engaging food hawkers, potential entrants, food hawker associations and the general public on a large scale.

2. Enforce higher premise standards in hawker centres

The hawker associations suggest that the state government establish state-owned hawker centres, with high premise standards to centralise quality food hawkers in chosen locations – a strategy that has been effectively implemented, for example, by the Singaporean government. These centres can be rented out to food hawkers at a reasonable rate and be continually improved upon, based on the feedback gathered.

Criteria such as a clean environment, good ventilation, centralised cleaning and efficient ingredient-purchasing services[11] should also be kept to boost the growth of state-owned hawker centres and raise the premise standards of hawker centres across Penang.

3. Promote the national retirement scheme to food hawkers

Even though food hawkers are eligible for the self-contribution national retirement scheme (previously known as the 1Malaysia Retirement Saving Scheme), the food hawker associations highlighted that many are unaware of the scheme, and those who are, do not see the need for them to contribute.

The scheme needs to be more actively promoted, for example, by transforming food hawking into a profession that is able to generate enough savings for retirement. The status of food hawkers as a legitimate career choice would be elevated, making it more attractive for new entrants.

4. Provide upscale assistance to existing food hawkers

With sufficient capital and entrepreneurial support, numerous food hawkers have successfully transformed their self-sufficient stalls into sustainable businesses[12]. Currently, food hawkers are able to apply for micro credit schemes through avenues like the Yayasan Penjaja dan Peniaga Kecil 1Malaysia (YPPKM).[13]

To encourage more upscaling, the state government could lend entrepreneurial support through stall-to-store expansions, or through the expansion of their distribution capabilities. An education on entrepreneurship and the establishment of a platform that connects aspiring entrepreneurs with interested food hawkers can also be explored.

5. Incorporate a module on Penang cuisine into the culinary arts programmes

According to a 2016 report by the Ministry of Higher Education, 532 culinary arts students were enrolled in five different educational institutions[14] in Penang. None of these institutions, however, have integrated a module on Penang cuisine as part of their curriculum – a close second is the study of Asian Food.

To cultivate interest in Penang cuisine, it is recommended that a culinary arts centre to preserve and promote the local food hawking heritage be established. It could also assist in the integration of the aforementioned module within the curriculum of existing culinary arts programmes, or better yet, it could develop its own programme.

6. Establish Penang cuisine entrepreneurship incubators

Interestingly, unlike previous generations where food hawking was a career option for those of low socioeconomic status or with limited education, youths today find it challenging to carve out a career in food hawking. Generally, they feel that they lack the necessary culinary skills. Under such circumstances, mentorship programmes should be introduced by pairing seasoned hawkers with aspirants to assist them in gaining a firm footing within the industry.

Temporary premises equipped with basic culinary equipment could also be provided to new hawkers, and further assistance be rendered when the hawkers decide to make a permanent transit into the industry.

7. Review the ban on foreign cooks

A complete ban on foreign cooks is ill advised, as it would signify a further reduction of food hawkers in the future. In fact, two food hawker associations raised some reservations about the restriction, highlighting the fact that some foreign cooks are skilled in the art of local cooking, and banning them would be a lost for the industry.

Instead, implementing a system to control the issuance of licenses could be a feasible way forward. Licenses can be issued to experienced foreign helpers and chefs on the recommendation by registered food hawkers or food hawker associations. Another option would be to issue licenses only to foreign cooks who have been certificated by a recognised culinary programme.

Conclusion

Sustaining the food hawking industry has unfortunately not been a prime item in both academic and public discourses despite it showing visible signs of decline in recent years. To preserve Penang’s food hawking heritage, it is therefore imperative that the state authorities gain a better understanding of the supply trend of food hawkers before policies are drawn and executed.

An in-depth study is needed to procure an accurate assessment on the sustainability of food hawking in Penang; and to redesign the profession as a viable career choice for the younger generation.

Appendix

A framework to analyse policy implications

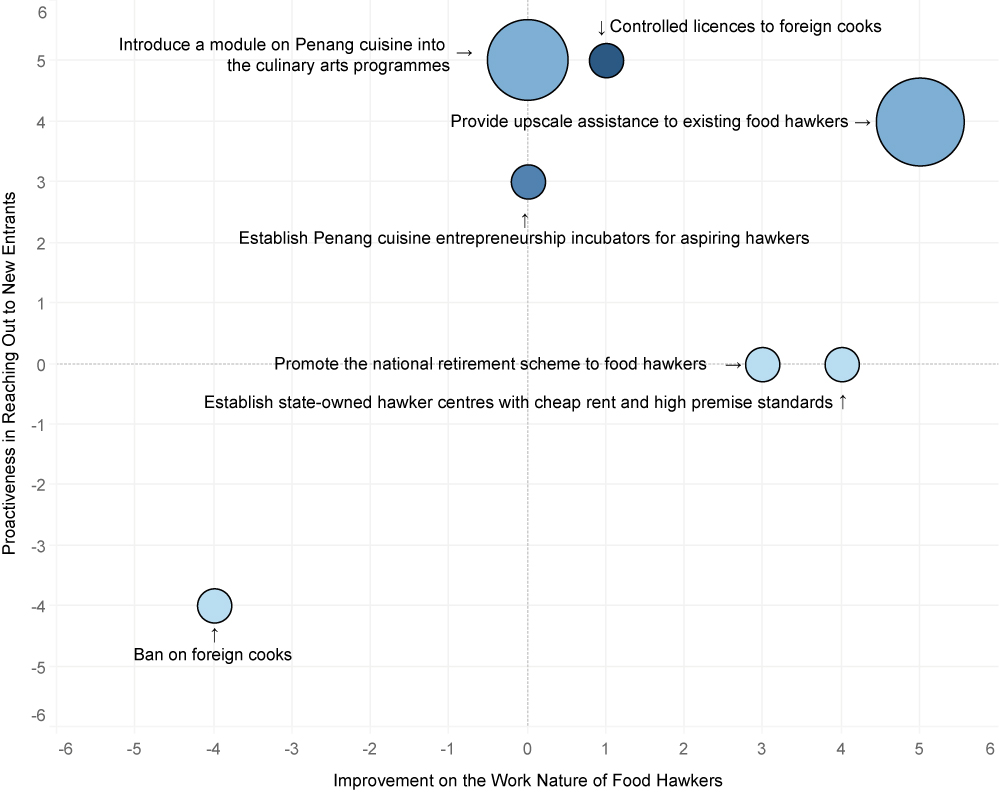

In undertaking initiatives to sustain the food hawking industry, the following factors need to be considered: the impact on the food’s price and taste; proactiveness in reaching out to new entrants; and improvements on the work nature of food hawkers.

The government should prioritise the aspects of food hawking it wants to preserve and determine an acceptance level for the negative impact on other aspects. A quadrant analysis could be used to visualise the impact of different policies based on the factors as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Visualisation of the different initiatives to sustain the food hawking industry using the proposed framework

Note: A negative score on the attributes “proactiveness in reaching out to new entrants” and “improvements on the work nature of food hawkers” indicates a negative impact on the respective factors. The size of the circle indicates the policy’s impact on the price of hawker food. A larger circle implies a significant increase in food prices in comparison to a smaller circle. Its colour is also indicative of the policy’s impact on taste preservation. A darker shade of blue illustrates a higher tendency of the policy to encourage culinary innovation, whereas a lighter shade demonstrates a higher tendency of the policy to not impact the authenticity and taste of Penang food.

The ideal strategy would be to maximise the score on “proactiveness in reaching out to new entrants” and “improvements on the work nature of food hawkers”, while minimising the impact on the taste and price.

Depending on the state government’s priority, different policies can be undertaken. For example, if the sole priority is to preserve the authenticity and taste of the local cuisine, then the 2016 policy to ban foreign chefs is a commendable effort. If, however, the priority is to preserve the continued easy availability of food hawkers, then a policy in the top right quadrant would be a better alternative.

References

Allain, A. (1988). Street foods: the role and needs of consumers. Yogyakarta: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Cheng, K. G. (2017). The cheapskate highbrow and the dilemma of sustaining Penang hawker food. Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia, 32(1), 36-77. ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute. Retrieved from https://muse.jhu.edu/article/657994/pdf

Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources. (2017). Hawker Centre 3.0 Committee Report. Singapore. Retrieved from https://www.mewr.gov.sg/Data/Editor/Documents/HC%203.0%20

Report.pdf

Pay Scale (2018). Kitchen Chef Salary (Malaysia) updated August 15. Retrieved from https://www.payscale.com/research/MY/Job=Kitchen_Chef/Salary

Department of Statistics Malaysia. (2017). Informal Labour Force Survey. Malaysia: Putrajaya.

Ministry of Higher Education. (2016). Profile of Private Higher Education Institutions. Malaysia: Putrajaya.

Fadzell, A. (2015, April 15). Najib launches hawkers, petty traders micro credit scheme worth RM30m. The Sun Daily. Retrieved from http://www.thesundaily.my/news/1373460

Omar, S. I. & Mohamed, B. (2017). Penang Tourist Survey 2016. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316738046_Penang_Tourist_Survey_2016

Penang banned foreigners from cooking assam laksa, hokkien mee and CKT in 2016. (2018, June

22). The Star Online. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2018/06/23/penang-implemented-ban-on-foreign-cooks-in-2016/

Peridon, G. (1990). Assessment of the economic impact of street foods in Penang, 1-88. Malaysia Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Season With Spice. (n.d.). Story of Penang Asam Laksa. Retrieved from http://blog. seasonwithspice.com/2011/09/what-is-penang-assam- laksa.html

Simopoulos, A. P. & Bhat, R. V. (2000). Street foods, 86, 53-99. Basel: Karger.

Tam, A. (2017). Singapore hawker centers: origins, identity, authenticity, and distinction. Gastronomica: The Journal of Critical Food Studies, 17(1), 44-55. Retrieved from http:// gcfs.ucpress.edu/content/17/1/44

Tarulevicz, N. (2018). Hawkerpreneurs: hawkers, entrepreneurship, and reinventing street food in Singapore. Revista de Administração de Empresas, 58(3), 291-302. Retrieved from https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s0034-759020180309

[1] The Penang Tourism Survey 2016 reports that 46.3% of tourists listed “trying local cuisine” as the number one must-do activity in Penang.

[2] A study done by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations back in 1990 estimates that food hawking generates 12% of the professions in Penang (Allain, 1988).

[3] Food hawking is categorised under the informal sector.

[4] A multi-disciplinary committee appointed by the Singaporean government to review the management and sustainability of the food hawking industry.

[5] The interviewed food hawkers sell Char Koay Teow, Koay Teow Th’ng, Chee Cheong Fun, Hokkien Mee, Laksa, Curry Mee, Chicken Rice, Bah Kut Teh, Porridge, Nasi Melayu, Satay, Mee Kuah, Mee Goreng, Apom, Curry Puff and Pan Mee.

[6] The three food hawker associations are Persatuan Peniaga-Peniaga Kecil Seberang Perai Utara, Penang Hawkers’ Association, and Persatuan Penjaja Seberang Perai Tengah.

[7] The income of food hawkers was estimated by multiplying the number of plates sold per day with the average price of the dish. Twenty percent is then deducted from the revenue to estimate the profits earned. The average price was calculated based on the price displayed at the respective food hawker stalls. The estimated cost price of 20% was estimated by one of the food hawker associations interviewed.

[8] The working hours stated do not include the preparation and cleaning done outside standard business hours.

[9] The mean and median age of the food hawkers from the study is 50 years old.

[10] For example, Penang Asam Laksa was initially created by the Malay fishing community using scrapped fish. Chinese settlers who had married into Malay families introduced other spices into the dish, leading to the flavours we know today.

[11] Fresh ingredients could be purchased from the market and delivered to food hawkers daily for a small fee.

[12] Examples include Hon Kei Food Corner, Penang Road Famous Teochew Cendol, 7 Village Noodle House & the Nasi Lemak Project.

[13] Launched by the federal government in 2015, YPPKM manages a micro credit scheme for Chinese hawkers and petty traders.

[14] These institutions include KDU, INTI, Atlas, MSU and SEGi. Culinary institutions that were not included in this preliminary study are PTPL College, Golden Chef College of Culinary Arts and CAC Academy.

Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng, Editorial Team: Regina Hoo, Nur Fitriah, Ong Wooi Leng

You might also like:

![Reconnecting Accountability Chains to Reform State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs)]()

Reconnecting Accountability Chains to Reform State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs)

![Fighting Covid-19 with Collaboration and Connectivity in Medical Science and Information Technology]()

Fighting Covid-19 with Collaboration and Connectivity in Medical Science and Information Technology

![Whistle-blowing as an Islamic Imperative: Empowering Muslim Civil Society Towards Good Governance]()

Whistle-blowing as an Islamic Imperative: Empowering Muslim Civil Society Towards Good Governance

![Crafting Employment for Persons with Learning Disabilities is a Sound Socio-economic Stratagem]()

Crafting Employment for Persons with Learning Disabilities is a Sound Socio-economic Stratagem

![[Rapporteur Notes] Penang Economic Summit 2022: The Post-Pandemic Economic Reset]()

[Rapporteur Notes] Penang Economic Summit 2022: The Post-Pandemic Economic Reset

![[Rapporteur Notes] Penang Economic Summit 2022: The Post-Pandemic Economic Reset](https://penanginstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/thumbnail-1-150x150.jpg)