Executive Summary

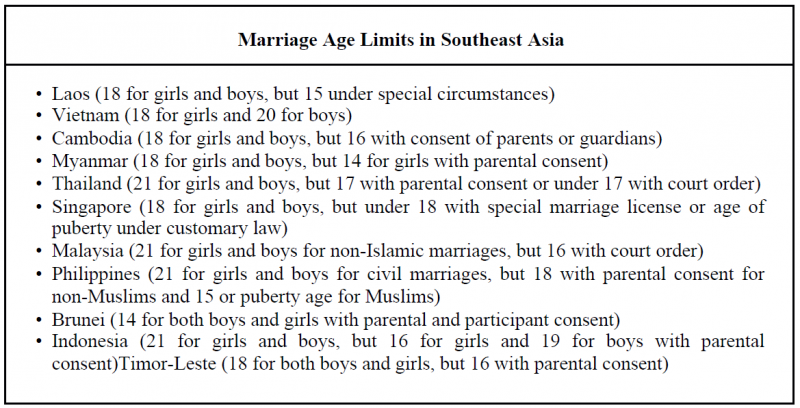

- Child marriage is the formal or informal union of any individual below the age of 18 and it is a violation of human rights. While the legal age of marriage in the Southeast Asia region countries varies between 18 to 21, (with the exception of Brunei), customary and religious laws still facilitate child, early and forced marriages (CFEM).

- Child marriage puts young girls at risk and perpetuates the poverty cycle. It also blunts the economy as it will lower female participation in the workforce.

- Entrenched patriarchal system, acute poverty, local cultural tradition, a lack of education and employment opportunities are some of the factors that drive child marriage in Southeast Asian countries.

- The debate which stunts the eradication of child marriage are – (1) the differing views of when does a girl become a woman and (2) the debate between cultural exceptionalism and universal human rights.

- To eradicate child marriage, governments across the region need to recognize the dire consequences of child marriage, to allocate resources to develop rural areas, provide education and employment opportunities for girls and, enforce child marriage act, appoint more female in political leadership and work closely with NGOs and INGOs. Eradicating child marriage in the Southeast Asia region also requires the commitment of local cultural and religious gatekeepers

Introduction

UNICEF defines child marriage as the formal or informal union between a child under the age of 18, and an adult or another child. By international norms, child marriage is a violation of the human rights. Children under the age of 18 are usually considered not fully aware of what the marriage entails, and many affected children often have little say in such unions and are likely to have been forced into such unions.

The consequences of child marriage, especially to girls can be dire. It effectively ends their childhood, increases their risk as victims of domestic violence, curtails their education, stunts their economic and social empowerment opportunities, exposes them to high-risk pregnancies, and causes depression. Infants born of adolescent pregnancies also tend to have a lower quality of life. Beyond the human costs, there is also the economic consequences to child marriage. Child marriages practiced commonly tend to lower female participation in the workforce and perpetuate society’s poverty cycle. In countries where child marriage is high, governments are likely to spend more on welfare.

Child marriages in Southeast Asia

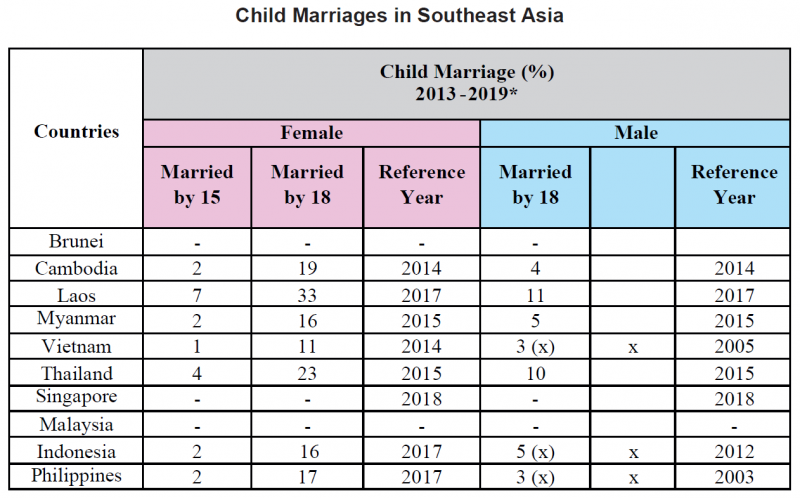

The international NGO, Girls Not Brides, states that 12 million girls are married before the age of 18 every year. In Southeast Asia, child marriage is not uncommon in rural areas where poverty is acute. The table below shows the percentage of child marriages in the region.

Indicator definitions

1. Percentage of women aged 20 to 24 years who were first married or in union before age 15

2. Percentage of women aged 20 to 24 who were first married or in union before age 18

3. Percentage of men aged 20 to 24 years who were first married or in union before age 18

4. – Data not available

5. X Data refer to years or periods other than those specified in the column heading. Such data are not included in the calculation of regional and global averages

6. *Data refer to the most recent year available during the period in the column heading

Factors Driving Child Marriage

Factors driving child marriage across Southeast Asia are varied, and include: entrenched patriarchal system, poverty, religious and cultural traditions, lack of education and lack of job opportunities. These aspects often overlap. Even so, the many loopholes in the marriage laws in the region are a major contributing factor.

Local Customs Precede International Norms

As indicated in the table below, the legal age of marriage in Southeast Asian countries varies between 18 to 21 years old (with the exception of Brunei). However, there are many loopholes for bypassing these regulations. Customary or religious law, parental consent and court orders can still be obtained to facilitate child marriage. This clearly shows that local customs still precede international norms. More critically, religious laws within the region run parallel with civil law, which further complicates the issue of child marriages.

For example, in the southern part of Thailand, namely Narathiwat, Yalla and Pattani where the population is mainly Muslim, Islamic law is applied to family matters. Girls who have started menstruating are seen as women and are considered ready for marriage. Exacerbating this, poverty which is not uncommon in this area also drives families to arrange marriage for these young daughters. As it is rather easy to arrange young girls into unions in these provinces, some Malaysian Muslim men cross the Thai border to seek young brides as their second or third wives, and putting many young girls at risk (Ellis-Petersen 2018). Under Islamic law, Muslim men are allowed four wives.

Likewise, in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Mindanao (BARMM) in the Philippines where most of the 3.8 million residents are Muslims, child marriage continues to be practiced (Robles 2020). Under the Code of Muslim Personal Laws, the marrying age for Muslim girls is 15, but younger girls can be married if they have reached puberty. In October 2020, Senate Bill 1373, which criminalises marriage between an adult and a minor was unanimously approved by the Philippine Senate. Even so, the Bill will be difficult to enforce since secular law and religious law run parallel. Despite the new legislation, it is likely that communities in BARMM will continue to follow the Code of Muslim Personal Laws.

In Indonesia, parents of a couple who are under the legal age of marriage can request for a marriage dispensation to the Religious Court (for Muslims) and non-District Court (for non-Muslims). But there are many ambiguities surrounding the marriage dispensation mechanism. A study by UNICEF Indonesia found that it is easier to obtain marriage dispensation in the religious court as compared to the district court. For example, from 2013 to 2015, there were a total of 377 rulings on marriage dispensation issued by Religious Courts in Tuban (East Java), Bogor (West Java) and Mamuju (West Sulawesi) (UNICEF Indonesia 2019). However, no cases have been recorded in the District Courts in Bogor and Mamuju since 2003, and in Tuban since 2011. The study also contends that the numbers of child marriages could be higher as there are also cases where children are wedded under customary laws.

Patriarchal system

Acceptance of child marriage is reinforced in communities that follow a strict patriarchal system. Within the region, it is not uncommon for girls or women to be treated as subjects of their fathers or husbands. Sons are favoured and there is more willingness to spend resources on boys in the family. In some extreme cases, the value of a married woman is heavily ascribed to the production of male offspring.

Beyond gender discrimination, girls also suffered from gender-based violence through traditional practices such as female genital mutilation (FGM), pre-natal sex selection, domestic violence and honor killings. In Southeast Asia, such cases may not be prevalent, but they do occur. For example, an honor killing occurred in Indonesia in May 2020 (Chew 2020). The victim, Rosmini Darwis, 16 was hacked to death by her male cousins for being in a relationship with a boy. Her romantic relationship was considered to have defiled family honor and her own virtue. This case clearly illustrates the entrenched patriarchal system and the misaligned power between female and male. While girls are treated as the subjects of men, men naturally assume the unchallenged role of being guardians of virtue.

An entrenched patriarchal system as such has very low tolerance for girls veering off from the traditional ascription of how girls should behave. Dating a boy at a young age without parental consent is shunned at best and is seen as sullying the family name at worst. To prevent such occurrences, families are motivated to marry their daughters young and the rationale is to protect the girl’s virtue and the family reputation. Certainly, acute poverty also plays a role (more on this is discussed below).

Marriage is also seen as a solution for young girls who get pregnant. It is an easy face-saving solution and prevents the birth of an illegitimate child.

Poverty

Where poverty is acute, there is a higher risk of child marriage. Families may consider marrying off their daughter to relieve their financial burden.

Dowry also serves as an incentive for poor families to arranged their young daughters into marriage. In Vietnam, for example, some girls are given up voluntarily by families on the understanding that they will receive a dowry, one that is somewhat less than the price of a buffalo (Yen 2018). Laos serves as a case study of how poverty exacerbates child marriages. In 2015, 43% of Laotian girls from minority groups and rural areas were found to have married before they turned 18 (Breese et.al 2017). Minority groups in Laos usually live under very poor conditions and have to struggle for social mobility. In some cases, a child can be offered in marriage as settlement of loans or financial dispute. The girls often have little say to resist such kind of forced marriages.

Similarly, poverty also drives many Indonesian girls into marriage. Children from rural areas and from poor households and had a low educational background tend to be more vulnerable to child marriage (UNICEF and Puspaka 2020). A comparable trend can also be observed in rural areas in The Philippines.

Local Culture and Practice

Local culture and practice is another factor that put young girls at risk of child marriage. For instance, the Hmong or Khmu practise Tshoob nii, literally meaning ‘bride theft’; young girls are kidnapped as brides. The victims can be as young as 12 or 13 years old. The girl is forced to marry the kidnapper and a bride price is then exchanged between the families of the bride and her kidnapper (Breese et. al 2017). The Hmong tradition in Meo Vac, Vietnam also stipulates that once a girl has spent three days in a boy’s house, she is married. Parents of the girls can rarely intervene, and they tend to learn of the mishap after the fact, when it is already too late to undo the damage (Jones et.al 2014).

Cross-border Demand for Brides

China’s one-child policy, though now relaxed, has created a serious gender imbalance where men outnumber women by far. Consequently, men from China have to look to other countries to find a wife. This demand for brides in China exacerbates the problem of child marriages in neighbouring countries such as Vietnam and Laos, and has inadvertently created space for criminals to traffic young girls. Stories of young women from rural parts of Vietnam ending up as brides in China is no longer novel. Some of the girls are lured by false promises of jobs while others are trafficked by their relatives, friends or boyfriends. And victims can be as young as 13 years old (Ng et.al 2019). While some become young brides to Chinese men, others end up working in brothels as involuntary sex workers.

Lack of Education and Job Opportunities

The lack of education opportunities also enhances child marriage. When children are uneducated, it is difficult for them to be employed in semi-skilled or skilled professions. And if their mothers and the elder women in their communities had also been denied education opportunities, young girls are conditioned to think that they will also live a life defined by marriage, child birth and domestic house chores.

Likewise, a lack of job opportunities will also spur child marriage. When girls do not have jobs that can empower them or their families, getting married becomes an urgent and natural step to take in life. Some may be lucky enough to marry a person of their choice, but many others have to succumb to pressure from family and community.

A General Discussion

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) together with UNICEF, UNFPA and Plan International has called for the ending of Child, Early and Forced Marriage (CEFM) against children in 2019 (ASEAN 2019). It has also adopted the Regional Plan of Action on the Elimination of Violence against Children (RPA), 2016-2025 in year 2015. The RPA provides a comprehensive roadmap to implement the 2013 ASEAN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Children. Be that as it may, the challenges remain formidable. At present, governments across the region have continued to accommodate local cultural practices and religious or customary laws that allow child marriages.

One major obstacle in eradicating child marriage is the debate of when a girl actually becomes a woman. While international standards consider an adult as someone who has reached the age of 18, some cultures continue to deem puberty as the criterion for womanhood, which could lower the age limit down to 12 years old. But this line of thinking is problematic as it only takes the biological aspect in consideration, and ignores the intellectual and emotional aspects of the child’s well-being. At that young age, a girl is hardly emotionally or mentally mature enough to take on the challenges of being a wife and a mother. Even when a girl is biologically ready for pregnancy, early childbearing can be risky for the young mother and the child. As it is, babies born to mothers under 20-24 years old face risks of low birth weight, severe neonatal conditions and preterm delivery. And mothers aged 10-19 face higher risks of eclampsia, puerperal endometritis and systemic infection than women aged 20-24 (WHO 2020).

The next barrier that stunts the effort of eradicating child marriage is the perennial debate of human rights versus cultural exceptionalism. Many conservative community leaders within the region do not accept the idea of universal human rights. Claims of preservation of traditional practice, or religious justifications are often used to legitimise child marriages. At its crux, the debate tends to lead back to the intractable question of whether human rights are merely a reflection of Western values or truly universal values. Communities that adhere to a strict patriarchal system or subscribe to religious dogma may therefore have a harder time reconciling their system of belief with universal human rights; and the idea that a girl has inalienable rights is unacceptable or unthinkable.

It is worth noting that the line of defense against the universality of human rights extends to the state level. Southeast Asian countries tend to use terms such as “diversity” to deny the universality of human rights and this includes the issue of child marriage. Furthermore, governments in Southeast Asia fear that criminalisation of child marriage may invite resistance from local authorities and may even raise tensions between central and local governments. Therefore, it is not surprising that many countries in the region do not prioritise the eradication of child marriage.

Regardless of how controversial the issue may be, there is a need to question and even challenge assumptions that defend child marriage. Governments in the region need to engage local gatekeepers and to help them understand the dire consequences of child marriage. Perhaps, it has to begin by firstly acknowledging the fact that a girl is not ready to be married just because she has reached puberty. Local community leaders also need to realize that universal human rights are not necessarily incompatible with cultural practices or religious values. Instead, they need to be made aware that forcing a child into a union is in fact inhumane.

In short, promoters of child marriage should not be allowed to hide behind the curtain of cultural preservation or traditional practice. They need to be identified and to be engaged, perhaps even punished. There is certainly a wide chasm between holding to one’s beliefs and doing so at the expense of children. While legislation is important, eradicating child marriage also necessitates the commitment of the local community and local leaders.

Policy Recommendations

Eradicating Child, Early and Forced Marriage (CFEM) in the Southeast Asia region is going to be slow, and fraught with much challenges. Even so, there are some suggestions that governments can adopt and adapt appropriately to their local context.

1. Recognize Dire Consequences of Child Marriage

Eradicating child, early and forced marriages has to begin with recognizing their dire consequences. Cultural or religious leaders may or may not agree with the idea of universal human rights but they cannot deny the consequences of child marriage to young girls and to the wider economy. There is abundant evidence that shows that child marriage poses health risks to young girls such as complications during child birth and even mortality risks. They are also at risk of becoming victims of domestic violence. On a societal level, children who end up in child marriage are also unlikely to be employed, and this also blunts the economy.

2. Enforcement of the Child Marriage Act

Governments need to take a strong stand to defend the marriage Act and do away with ambiguities and loopholes. Instead of being discussed within the parameters of family matters or in a religious or cultural context, child marriage should be discussed as an issue affecting the public interest.

3. Develop Rural Areas and Create Job Opportunities

As indicated in the examples discussed above, child marriages often happen in rural areas because of poverty and a lack of education and employment opportunities. Hence, government should allocate more resources to develop rural areas and to create more job opportunities such as building more schools, training centres and even general facilities to improve mobility. When young girls are trained and employable, they contribute to their family income. In turn, it will help alleviate poverty and reduce the pressure on family to marry off their daughters.

4. Access to Education

Governments need to ensure that girls have access to primary and secondary school. Age-appropriate education on sexual and reproductive health should be incorporated into the school curriculum as well. There is also a need to facilitate girls returning to school if they have dropped out because of pregnancy or early marriage. At the same time, counselling services have to be provided in schools for girls who are at risk of being into forced marriage or of facing domestic violence.

5. Increased Qualified Women at Higher Level of Political Leadership

To eradicate child marriages, governments also need to increase qualified women at higher levels of political leadership. Female leaders would be more sensitive to issues that concern children and probably more committed to lobby for the eradication of child marriage.

6. Work with grassroots movements and NGOs

Governments also need to work closely with grassroots movements, and regional and international NGOs. These are the agencies that can provide relevant information and effective policy recommendations. Such agencies can also help develop culturally appropriate strategies that are workable in specific local contexts.

Conclusion

Eradicating child, early and forced marriage (CEFM) in the Southeast Asia region will be an uphill battle especially when there are numerous communities in the region still beholden to cultural dogma or are deeply entrenched in a patriarchal system.

ASEAN has taken some steps to eradicate CFEM, but policy makers need to be aware that the eradication of child marriage has to be a two-way approach. While they legislate and enforce laws, the wider society also has to be engaged and encouraged to embrace the idea that girls need to be protected and given equal attention as boys. As long as girls cannot grow up to have access to equal education and employment opportunities, child marriage will continue and the individual costs will mount calamitously, as will the economic detriments.

For list of references, kindly download the document to view.

Editor: Ooi Kee Beng

Editorial Team: Sheryl Teoh, Tan Lii Inn, Alexander Fernandez, and Nur Fitriah (Designer)

Image by Agnieszka Kowalczyk (Unsplash) is for illustration only

You might also like:

![Deconstructing Trump’s Tariffs: The Impact on Penang’s Trade and Economic Resilience]()

Deconstructing Trump’s Tariffs: The Impact on Penang’s Trade and Economic Resilience

![Covid-19 Fuels Democratic Decline in Southeast Asia]()

Covid-19 Fuels Democratic Decline in Southeast Asia

![Imagine an Education Hub: Leveraging Penang’s International School Ecosystem]()

Imagine an Education Hub: Leveraging Penang’s International School Ecosystem

![Breaking Old Habits is Vital for Malaysia’s Mainstream Newspapers]()

Breaking Old Habits is Vital for Malaysia’s Mainstream Newspapers

![From Means of Survival to Tourism Gems: A Study of Street Food Prospects in Penang]()

From Means of Survival to Tourism Gems: A Study of Street Food Prospects in Penang