Executive Summary:

- On 2 April 2025, the Trump administration declared a national emergency over persistent US trade deficits, subsequently imposing baseline universal tariffs on imports along with reciprocal rates on its trading partners.

- These tariffs are linked to a broader economic framework known as the “Mar-a-Lago” Accord, a currency agreement that leverage tariffs to pressure trading partners into currency appreciation against the US dollar.

- Effective August 1, Malaysia could be facing a 25% reciprocal tariff (as of 29 July). For Penang’s export-driven economy, these tariffs pose a threat of trade diversion and supply chain relocation, despite some high-valued exports such as electrical machinery and memory chips initially receiving exemptions.

- In response, Malaysia has adopted an independent and neutral stance in face of the US tariffs. Meanwhile, Penang is taking a wait-and-see approach while exploring strategies like export diversification and market expansion.

Introduction

On 2 April, 2025, US President Donald Trump declared “Liberation Day,” enacting sweeping tariffs on nearly all imported goods to address substantial and persistent US trade deficit, attributing it to what he described as “unfair trade practices” from its trading partners. Effective 5 April, a baseline 10% rate will be applied on all US imports. This was followed with additional “reciprocal” tariffs on all of US trading partners, each with differential rates that go as high as 50%.

These reciprocal tariffs target countries with significant US trade surpluses, including key Asian partners like Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, and Indonesia. Though initially set for 9 April, these reciprocal tariffs were postponed to 9 July to allow for negotiations. At the time of this writing, on 7 July, Trump announced new tariff rates on 14 countries, with Malaysia now facing a 25% tariff rate, effective on 1 August (Breuninger, 2025).

Experts and economists have widely criticized these measures as potentially disruptive to the existing multilateral order, as steep universal tariffs create widespread uncertainty among policymakers and businesses. But beyond Trump’s protectionist ideals, these tariffs appear to be integral to a broader, comprehensive strategy designed to fundamentally rebalance global trade dynamics in favour of the US.

This article is structured in two sections; the first analyses the core rationale and underlying causes behind the implementation of these tariffs, including an outline of the unconventional and controversial blueprint proposed by the Trump administration. The second section delves into the specific challenges these tariffs present for Malaysia, with a focus on Penang’s trade economy, and explores how the nation is positioning itself within this changing global landscape.

1 The Rationale behind US Tariffs

1.1 Restoring fairness and protection in US trade

The Trump administration’s trade policy is rooted in the ‘America First” agenda, aiming to strengthen economic and national security while ensuring fairer trade to the American people. In his second term, Trump’s latest trade agenda seeks to transform the country into a “production economy,” by leveraging tariffs and export restrictions to revitalize domestic manufacturing and strengthen national security (USTR, 2025).

The core rationale is that persistent trade deficits are caused by unfair non-reciprocal trade practices by other nations that undermined US trade competitiveness. For instance, the administration cited the current US tariff rate for rice paddies is the ad valorem equivalent of 2.7%, while Malaysia imposes a much higher 40% rate. In another case, Trump claimed the EU imposes discriminatory import tax on US-made automobiles (The White House, 2025a).

To address this, the administration devised a new and widely criticized approach for determining the reciprocal tariff rates. These rates are calculated based on bilateral trade deficits as a share of their total exports, rather than the existing duties levied by these countries (Corinth & Veuger, 2025). For example, Malaysia, with a $24.8 billion trade surplus with the US have exported $52.5 billion in 2024. The calculation yielded approximately 47%, which was halved to 24% as the proposed reciprocal tariff (USTR, n.d.).

Trump’s trade policy reflects a clear preference for unilateralism, where the US wants to act independently to assert its economic interests, rather than relying on multilateral agreements that equally benefits all parties. This shift was evident from the administration’s 2017 withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a 12-nation agreement that comprises 40% of the world GDP (USTR, 2017). Instead, Trump favours individualized deals that would grant the US greater control over terms. A recent example is the June agreement with the UK, where both nations agreed to remove non-tariff barriers on all US products, while the US maintains a tariff on UK automobiles (The White House, 2025b). More recently, Trump has also threatened an additional 10% tariffs on BRICS nations, quoting that countries aligning with “Anti-American” policies would face further repercussions (Batchelor, 2025).

1.2 The root cause of US trade deficit

According to Stephen Miran (2024), the current chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, the persistent US trade deficit is caused by the overvaluation of the US dollar and the consequence of the Triffin Dilemma (Miran, 2024). Coined by the Dutch Economist Robert Triffin, this paradox stems from the US dollar’s role as the global reserve currency status, which requires the US to run continuous account deficits to supply the world with sufficient dollars – through imports, foreign investments, and other expenditures to ensure global economic stability. While stripping the dollar of its reserve status would address the dilemma, it risks global instability due to the massive liquidity shortage which would ensue.

Despite these drawbacks, the dollar strength as a reserve currency provides the US with a distinct advantage. The US can exert financial influence globally without the use of military force, as Miran highlighted; the US can also sanction countries by restricting their access to the US banking system and freezing critical assets. Given this extraordinary leverage, the US has little to no reason to give up its currency reserve status.

1.3 A blueprint for a new trade order

Miran (2024) articulated a vision for a new global trading system that aims to rebalance US trade without sacrificing the dollar’s reserve currency status. In his white paper, “A User’s Guide on Restructuring the Global Trading System,” he proposed the “Mar-a-Lago” Accord. The accord would have objectives similar to that of the Plaza Accord of 1985, where the US, France, Germany, UK, and Japan coordinated to weaken the dollar through direct market interventions. The only difference is that the Mar-a-Lago Accord would leverage tariffs to pressure countries to appreciate their currencies against the US dollar through foreign exchange intervention. More specifically, the US would offer to lower tariffs imposed on Liberation Day if the country agreed to sell its holdings of US government bonds from its central bank reserves in exchange for its own currency (Patterson, 2025).

Within this framework, Scott Bessent, the Trump administration’s current treasury secretary, proposed a tiered incentive structure. The system classifies countries in three buckets: “green,” “yellow,” and “red,” based on their willingness to participate in the accord or align with other US security objectives. The basket also links trade and economic access to US security guarantees. For example, countries like Taiwan, which faces geopolitical threats and relies on US security commitments, are more likely to conform to the accord and be placed in the “green” bucket, thereby benefiting from the US security umbrella and full access to the US market with lower tariff trades. Conversely, countries deemed adversarial and uncooperative, such as China, would almost certainly fall into the “red” bucket, facing higher tariffs and limited access to the US market.

2 Malaysia’s Outlook in the New Trade Order

2.1 Penang’s export landscape

The Trump administration’s ambition to rewrite the current global trade order carries significant implications for the rest of the world, especially in an era where supply chains are integrated globally. Malaysia is a vital player in the electronics and semiconductor global supply chains and produced 13% of the global semiconductor packaging, assembly and testing market in 2024 (Invest Penang, 2024). Trump’s proposed 25% (as of 29 July) reciprocal tariff on Malaysian exports poses a substantial threat to its export-oriented economy.

Penang, often called the Silicon Valley of the East largely due to its reputation as the major manufacturing hub of electrical and electronic products, produced about 5% of global semiconductor exports in 2019. Its robust ecosystem consists of over 350 MNCs from the US, Japan, and Europe, alongside more than 4,000 local SMEs in the manufacturing and services-related sector (Buletin Mutiara, 2024).

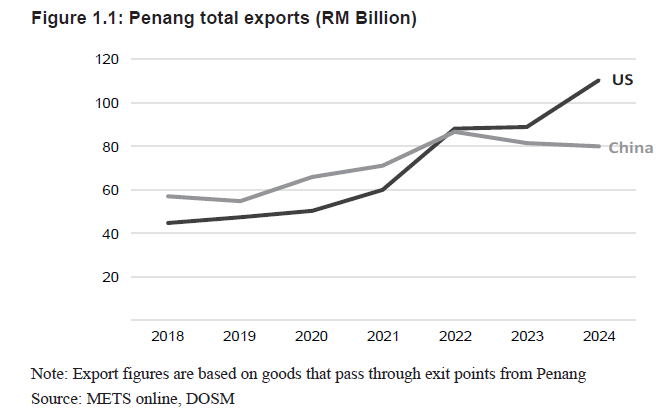

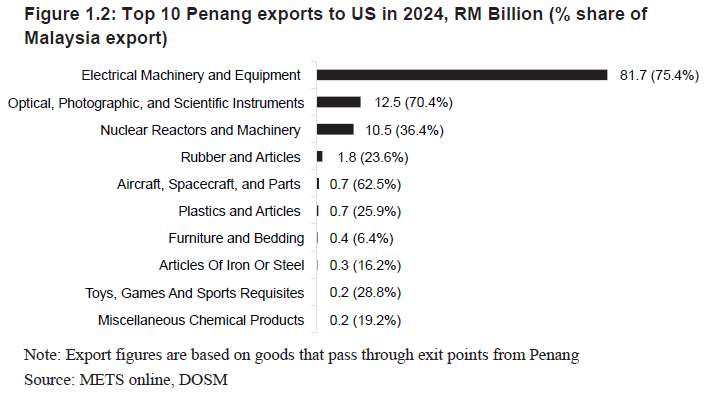

Penang is Malaysia’s most trade-dependent economy, with a heavy reliance on the US market. In 2023, the US surpassed China as Penang’s top export destination, reaching a record high of RM 110 billion in 2024 (Figure 1.1). A substantial portion of these exports consisted of electrical machinery and electronic parts, valued at RM 81.7 billion (Figure 1.2). Penang alone contributes about 75% of Malaysia’s total exports of these crucial products to the US.

2.2 The impact on Penang’s export industry

In recognition of the unprecedented tariff announcement and its potential impact on Penang’s export industry, the Chief Minister of Penang, Chow Kon Yeow, organized a roundtable discussion on 11 April. This discussion gathered federal and state policymakers, company executives, researchers, and trade association representatives to address the challenges, opportunities, and strategic responses to the recent U.S. tariffs.

According to industry players from the E&E sector, the immediate impact of US tariffs would see a decrease in Penang’s export competitiveness, largely due to increased business costs and foreign currency fluctuations. The tariff shock is also expected to trigger trade diversion and supply chain relocation. The Institute of Strategic & International Studies (ISIS) identifies three shifts from a trade diversion: positive trade diversion, negative out diversion and import diversion/dumping (Singh & Cheng, 2025).

According to Singh & Cheng (2025), positive trade diversion occurs when Malaysia becomes a more attractive alternative for foreign investments due to relatively lower tariffs. Since Trump’s 1.0 trade policy in 2018, Malaysia and particularly Penang, has significantly benefitted from the “China plus one” strategy, where MNCs diversified their supply chain operations beyond China. Participants in the discussion expressed optimism that Penang could continue to leverage this advantage.

Conversely, negative out diversion, or supply chain relocation, presents a notable issue for Penang. Given the substantial presence of foreign MNCs in Penang, there is a concern that US-based companies with manufacturing operations in the region might either re-shore their supply chains back to the US or near-shore to countries with lower tariff rates. Analyses by Singh & Cheng (2025) identified the Philippines and Mexico as potential beneficiaries of diversions due to favourable tariff rates and higher substitutability. Overall, this risk, amplified by Trump’s stated goal of bringing manufacturing back to US soil, could be highly detrimental to Penang’s industrial ecosystem.

Finally, the most alarming issue raised was import diversion or dumping. A positive trade diversion from China could lead to an excess influx of Chinese goods into Malaysia, potentially distorting local market competition and harming domestic industries. Singh & Cheng (2025) specifically reported that furniture, toys, machinery, and plastics from China are at higher risk of being dumped in Malaysia, with machinery and plastics facing the highest threats.

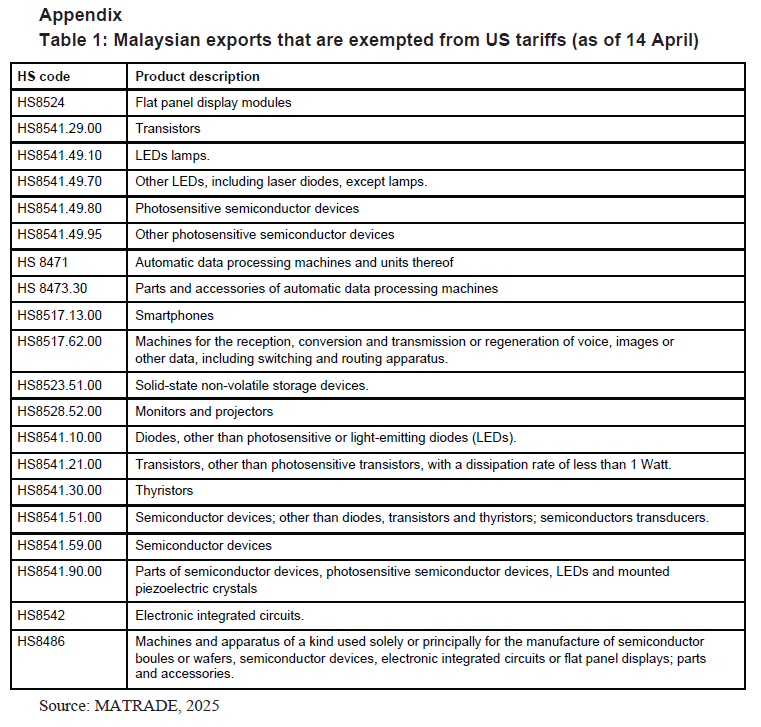

A silver lining for Penang is that a substantial portion of its high-valued exports, including semiconductor devices, processor parts, and electrical machinery will be exempted according to the White House (A detailed list compiled by MATRADE can be found in Table 1 in the Appendix). But despite these exemptions, Penang’s key exports remain vulnerable to future policy shifts, as the Trump administration could alter these exemptions during the ongoing trade negotiations before the August deadline.

Despite these challenges, industry stakeholders and policymakers in Penang are adopting a cautious “wait-and-see” approach while actively exploring strategies to navigate the new trade landscape. A key strategy involves increasing diversification in export destinations and investments, including enhancing domestic direct investments and expanding Penang’s industry to new and existing markets such as India and the ASEAN region.

2.3 Malaysia’s stance in the new trade order

Under Miran’s proposed framework, Malaysia could find itself in the “yellow” bucket, as Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim has repeatedly affirmed that the country will maintain a neutral and non-aligned stance against US pressures. In response to the “Liberation Day” announcement, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim has stated that Malaysia would not introduce retaliatory tariffs against the US, and seeks to engage in trade negotiations to avoid the 25% tariff rate. The Prime Minister has also remarked that Malaysia will remain “fiercely independent” against global hegemony, asserting that its strengthening ties with China do not impact its ongoing trade talks with the US (Prime Minister’s Office of Malaysia, 2025).

Regardless of the outcome of the US trade negotiations in August, Malaysia should actively leverage its ties with its ASEAN neighbours. Malaysia chairs ASEAN this year, and it is a crucial matter to intensify intra-ASEAN trade and foster economic resilience against external trade challenges, notably through strategic initiatives that includes harmonising trade standards and pursuing deeper financial integration (Azhar & Tang, 2025). Ultimately, strengthening its cross-border integration and increasing diversification are needed to navigate this changing global landscape.

References

Azhar, D., & Tang, A. (2025, May 27). Asean unveils strategic plan to integrate its economies. The Edge Malaysia.

Batchelor, V. (2025, July 7). Trump Threatens 10% Tariff for Nations Aligned With BRICS. Bloomberg.

Breuninger, K. (2025, July 7). Trump’s new tariffs will be in effect by August 1. Here’s what they mean for the economy. CNBC.

Buletin Mutiara. (2024, March 8). InvestPenang committed to facilitating investment. Buletin Mutiara.

Corinth, K., & Veuger, S. (2025, April 4). President Trump’s tariff formula makes no economic sense. It’s also based on an error. American Enterprise Institute.

Department of Statistics Malaysia. (2019). Malaysia External Trade Statistics (METS) Online – State Based on Exit and Entry Points. DOSM.

Invest Penang. (2024, March 11). Malaysia: The Surprise Winner from US-China Chip Wars. InvestPenang.

MATRADE. (2025, April 14). FAQs on the impact of US tariff as at 14/04/2025. MATRADE.

Miran, S. (2024). A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System. Hudson Bay Capital.

Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). (2025, March 3). The President’s 2025 Trade Policy Agenda. USTR.

Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). (n.d.) Malaysia Trade Summary. USTR.

Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). (2017, January 23). U.S. withdraws from TPP. USTR.

Patterson, R. (2025, March 26). Mar-a-Lago Accord Is Not a Recipe for Success. Council on Foreign Relations.

Prime Minister’s Office of Malaysia. (2025, April 7). YAB Prime Minister’s media talking points on the United States reciprocal tariffs. PMO Malaysia.

Singh, J., & Cheng, C. (2025, May). Trump, trade and tariffs: Impact on Malaysia. ISIS Malaysia.

The White House. (2025a, April 2). Regulating imports with a reciprocal tariff to rectify trade practices that contribute to large and persistent annual United States goods trade deficits. The White House.

The White House. (2025b, June 26). Fact sheet: Implementing the general terms of the U.S.-UK economic prosperity deal. The White House.

You might also like:

![Synergy among Stakeholders is Key to the Sustainability of Cultural Tourism in Penang]()

Synergy among Stakeholders is Key to the Sustainability of Cultural Tourism in Penang

![Breaking Old Habits is Vital for Malaysia’s Mainstream Newspapers]()

Breaking Old Habits is Vital for Malaysia’s Mainstream Newspapers

![A Non-state-centred System to Regulate ‘Fake News’?]()

A Non-state-centred System to Regulate ‘Fake News’?

![Report of the Penang State-Federal Relations Select Committee 01/25]()

Report of the Penang State-Federal Relations Select Committee 01/25

![Helping SMEs Rise to Challenges Posed by the Covid-19 Pandemic]()

Helping SMEs Rise to Challenges Posed by the Covid-19 Pandemic