MP SPEAKS MP for Serdang Dr Ong Kian Ming wrote an excellent article about the worrying gender imbalance in Malaysian public universities. Our colleagues in the Penang Institute have shown that women greatly outnumbered men in major public universities. In institutions such as Universiti Putra Malaysia, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris etc., female students constituted more than twice the number of male students.

Other top public varsities such as Universiti Malaya, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia scored between 1.5-1.99 in the Gender Parity Index (GPI), and are categorised as having “extreme disparity” with women outnumbering men.

Dr Ong correctly pointed out that “the presence of a reverse gender gap in our public universities raises other concerns such as the career trajectory of the ‘missing’ boys and potential negative impacts on crime and other social indicators”.

The corollary situation

However, the corollary situation is also a matter of grave concern: the ‘missing’ girls and women in our job market.

Although women dominate our public tertiary institutions, they often go ‘missing’ after graduation.

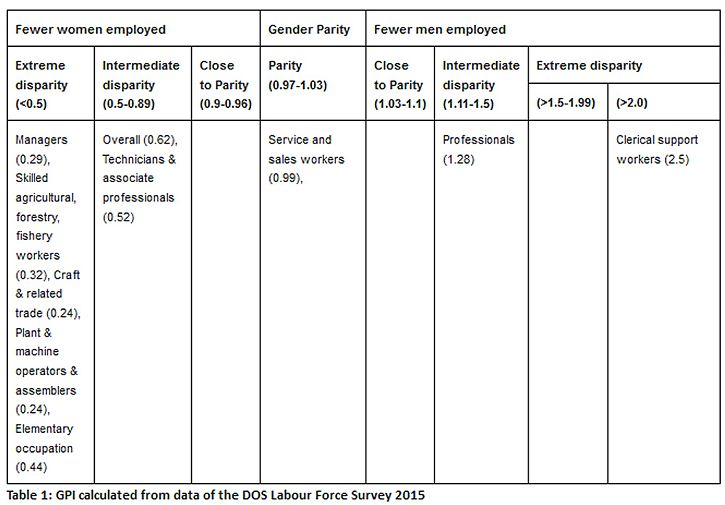

I will borrow Unesco’s Gender Parity Index used by Dr Ong to measure the relative participation of women and men in the job market. Similar to the Unesco index, the GPI for this purpose is calculated by the quotient of the number of females by the number of males employed in a particular sector.

The purpose for this, other than its simplicity, is also to better demonstrate the corollary of Dr Ong’s case by using similar measurement.

Using Dr Ong’s Unesco GPI of 0.97-1.03 as parity, while there is an overrepresentation of women in the clerical support workers sector (GPI 2.53), and in the professional sector (GPI 1.28), as well as parity in the service and sales sector (GPI 0.99), overall, women are still grossly underrepresented in the job market with a GPI of 0.62. (Source: Dept. of Statistics, Labour Force Survey 2015)

Dr. Ong pointed out that “45 percent of engineering undergraduates in Malaysia are female”. However, GPI for graduate engineers in the job market is 0.29 with women comprising only 22.7 percent in the sector in 2014.

While it is understandable that women are largely not in physically-demanding jobs such as plant and machine operators and assemblers (0.24), women are generally “missing” in decision-making and corporate leadership positions as well. The GPI for managerial position is 0.29 suggesting a situation of “extreme disparity” against female workers.

The situation is as bad if not worse at the board level. According to data from the Commission of Companies, women made up only 16 percent of corporate board members, equivalent to a GPI of 0.19.

Government-linked companies are not faring any better. For companies under the Finance Ministry Incorporated, women made up only 17 percent of board members.

Women senior civil servants are also very few, about 33.7 percent hold Jawatan Utama Sektor Awam (Jusa) – GPI 0.51.

At the highest leadership level in the civil service, seven out of 23 (30 percent) chief secretaries (ketua setiausaha) are women, while only 29 out of 151(19 percent) heads (ketua pengarah) of departments and statutory bodies are women. Overall, from heads of departments onwards up to the chief secretary, the GPI is 0.26.

Where are the women whose numbers surpassed men in our public varsities?

A 2013 survey conducted by TalentCorp and ACCA on “Retaining Women in the Workforce” found that the top factors for women leaving the workforce are: 1) to raise a family, 2) lack of work-life balance, 3) to care for a family member, 4) childcare is too expensive, and 5) lack of support facilities for women from employer.

The comprehensive list of reasons given mostly have to do with a woman’s commitment to her family and workplace gender discrimination such as the gender wage gap, opportunities for promotion, etc.

In today’s world, to choose between one’s family and one’s career are unfortunately a false dilemma posed to women. Often, it goes back to the culture of discrimination against women.

For women who took a career break to care for family, the same survey found that 93 percent of them wished to return to the work force, but 63 percent of them thought that there are major obstacles hindering them from doing so. They cited “career obsolescence and employer bias” as key barriers for re-entry; again gender discriminatorion factors.

Economic consequences of our missing girls and women from the market place

While it should be clear that empowering women in all aspect including in the workforce is about fairness and human rights, closing the gender gap in the job market also brings real and measurable economic benefits.

Firstly, tax money spent on subsidising public varsities will not be maximised if a major segment of our student population goes “missing” from the job market after graduation, especially if it is not by choice and is due to circumstances which can be reversible.

Secondly, there is a real concern about the qualification of our workforce when our graduates are not “turning up for work” for whatever reasons. Only about 27 percent of all employed persons in Malaysia have tertiary education.

Thirdly, the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report in 2014 confirmed “ a correlation between gender equality and GDP per capita, the level of competitiveness and human development… consistent with the theory and mounting evidence that empowering women means more efficient use of a nation’s human capital endowment and that reducing gender inequality enhances productivity and economic growth.”

McKinsey Global Institute reported that in a “full potential” scenario where women’s participation in the economy is identical to men’s, the annual global GDP in 2025 will increase upto 26 percent or US$28 trillion compared with a business-as-usual scenario. This is equivalent to the economies of US and China combined today. The report also projected an 8 percent increase in GDP for South-East Asia by 2025 in such a scenario, translating to about RM110 billion in our own economy.

Dr Ong is right to conclude that “just because female enrolment in IPTAs have far surpassed male enrolment does not mean that gender discrimination against females has disappeared.“ In fact, the missing girls and women from the job market should raise a red alert as much as the missing boys from public varsities. While the missing boys phenomenon is relatively new, missing girls is an old problem, often highlighted but yet unresolved till today.

STEVEN SIM CHEE KEONG is MP for Bukit Mertajam and deputy spokesperson, DAP Parliamentary Committee for Human Resources.