Executive Summary

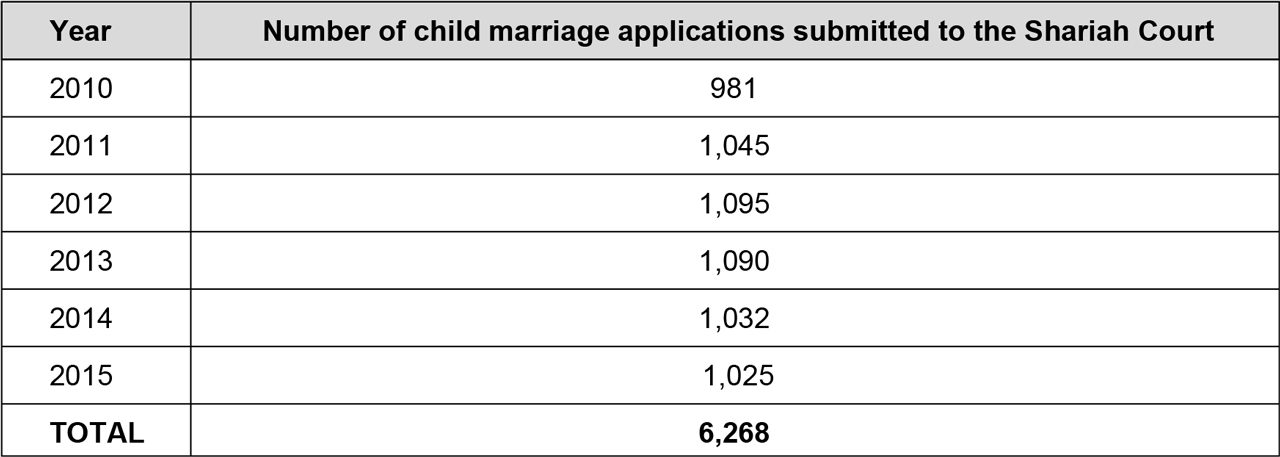

- Child marriage is not a fringe issue in Malaysia. There are nearly 9,000 such cases from 2010 to 2015 — 6,268 Muslims and 2,775 non-Muslims.

- Child marriage has been shown to negatively impact the child’s physical and mental health, reduce his or her education and economic opportunities, and increase the risk of domestic and sexual abuse.

- Minimal understanding about statutory rape (sex with minors) causes lawmakers and the public to trivialise the issue. Worse, Malaysia has an extremely low conviction rate for child sexual abuse cases. Hence, perpetrators and would-be perpetrators are either not aware of the offence or are not afraid of being punished.

- Child marriage is not a solution to pre-marital sex and social ills, but in some cases, the child is punished twice by having to marry her rapist and by being deprived of education, social mobility and economic opportunity. Child brides are prone to abuse and there have been cases of child marriage ending abruptly in divorce after a short period, leaving the child with a baby.

- Early intervention and education can greatly pre-empt and reduce statutory rape, child sexual abuse, teenage pregnancy and consequentially, child marriage. International examples have demonstrated early intervention (for example, mandatory education for boys and girls to teach consent, how to say “No”, how to react and report, and how to debunk rape cultures) is successful in reducing child sexual abuse and rape.

Introduction

The call to ban child marriage in Malaysia, most recently made in Parliament when a lawmaker submitted a proposal to amend the Sexual Offences Against Children Bill 2017 to include a ban on child marriage, has met with some resistance, and remains unacted upon.

The minimum legal marriage age for Muslims is 18 for men and 16 for women. For non-Muslims, it is 18 for both men and women. Child marriage is thus defined as marriage below the minimum legal age which requires the approval of a Shariah court judge for Muslims or the Menteri Besar / Chief Minister for non-Muslims. The Law Reform (Marriage and Divorce) Act of 1976 stipulates that under no circumstances can the marriage of non-Muslims below 16 years old be legally approved. Crucially, Muslims are exempted from this Act, hence in practice, there is no written absolute minimum age for them.

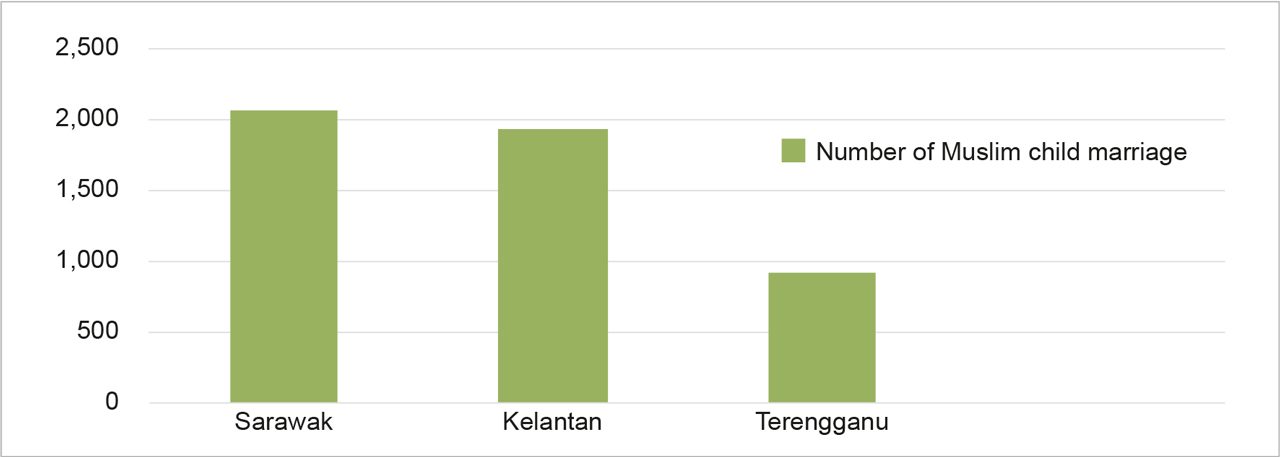

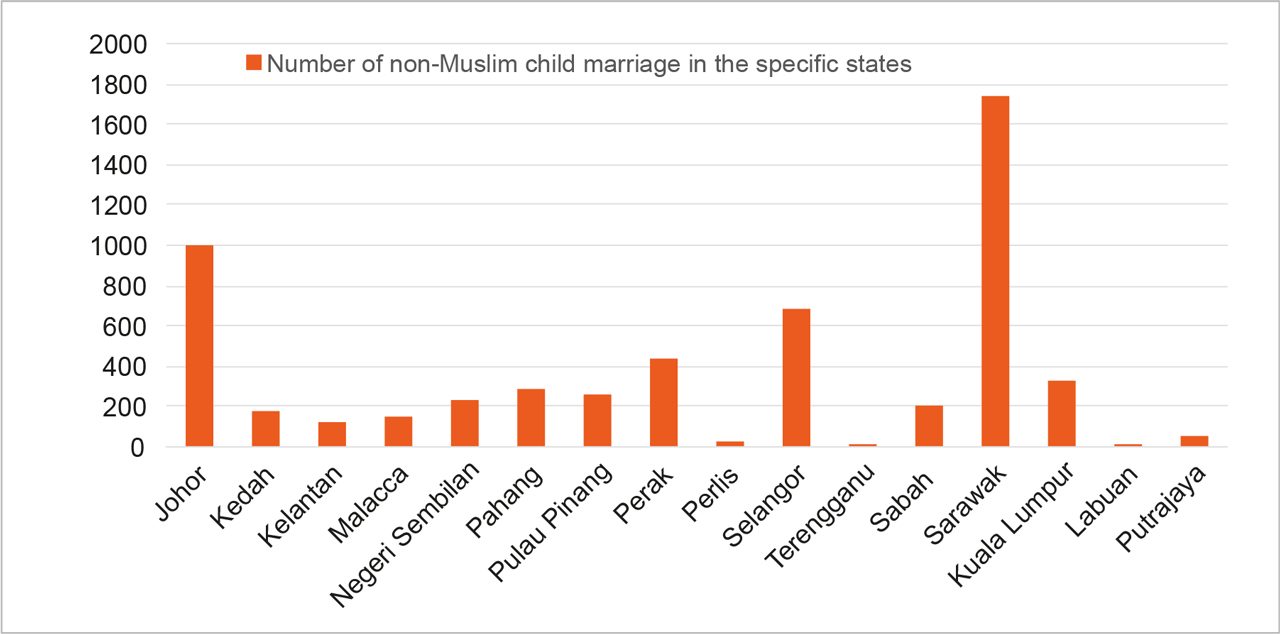

Child marriage is not a fringe issue in Malaysia. Between 2005 and 2015, 10,240 Muslims applied for child marriage to the Malaysian Shariah Judiciary Department (JKSM),[1] most of them from Sarawak(2,064),Kelantan(1,929)andTerengganu(924).[2] Amongnon-Muslims,therewere7,719 marriage applications made between 2000 to 2014 for girls between 16 and 18 years old.[3]

High Risk and Long-term Impact on the Child

Warnings against the long-term detrimental effects of child marriages have been repeatedly made by the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development, NGOs and researchers, not to mention international bodies like the United Nations. Their worry is a broad one.

Most immediately, what we are dealing with are cases of children being forcibly and suddenly exposed to sexual acts before they are physically and emotionally ready. The girls are at risk of bearing children before their bodies are physically mature for it.

Across 18 of the 20 countries with the highest prevalence of child marriage, girls with no education are up to six times more likely to marry early than girls with high school education[4] . Even otherwise, child marriage tends to lead to the children involved dropping out of school, usually permanently thus affecting their chances of getting better jobs and a higher standard of living that can come with better education.[5]

Girls who are married to much older men are also at much greater risk of suffering spouse violence than if they marry someone of the same age later in life.[6] The unfortunate start to their married life tends to lead to long-term abuse and trauma. In Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Zimbabwe, and Bangladesh, about half of married girls experience spouse violence (domestic or sexual abuse).[7] Child brides are also vulnerable and twice as likely to report being beaten, slapped or threatened by their husbands than adolescents who marry later.[8] In Bangladesh, 47% of married girls have experienced spouse violence. In a study in northern Ethiopia, 81% of child brides interviewed described their sexual initiation as forced.

Child marriage is objected to on religious grounds by Malaysia’s Muzakarah Jawatankuasa Fatwa Majlis Kebangsaan Bagi Hal Ehwal Ugama Islam (often shortened to Majlis Fatwa Kebangsaan; National Fatwa Council). The Fatwa Committee has declared child marriage an unhealthy practice that has deep detrimental impact on the child’s health and psychology[9] . It has urged that the Prophet’s marriage to Aishah not be used as an excuse for child marriage. Religious scholars (ulama) agreed that child marriage is neither compulsory nor encouraged by Islam (“bukan perkara yang wajib atau sunat”), and that there is no Hadith[10] that encourages such a practice. This group of Islamic scholars also called for a tightening of regulations on child marriage and for the principles of Maqasid Syariah and Fiqh[11] to be followed, to “avoid harm” to the children.

Abuse of the Shariah Court Process

Those opposed to a total ban on child marriages emphasise the legal provision for the Shariah court judge or the Menteri Besar / Chief Minister to exercise wise discretion in approving child marriages. This reliance on discretion on the part of the judge or the Menteri Besar / Chief Minister is a procedure that worries many. There is valid fear that this may easily become a mere procedural process. Looking at the approval rate for the many child marriage applications should give a hint of how the provision works.

According to JKSM data, the approval rate in 2015 was 81%. This does not vary much from the approval rates in 2011 (86.1%), 2012 (87.7%) and 2014 (74%). Out of ten child marriage applications, therefore, the Shariah court judge approved eight on average. However, the approval rate for underage non-Muslim marriage applications from 2015 onward are unavailable.

Whether the Shariah court judge or the Menteri Besar / Chief Minister of various states have a specific taskforce or sub-department to brief and assist them in making a proper evaluation, or to solicit advice from various agencies under their charge (such as the Welfare Department) is not clear.

The executive, legislative and judiciary branches of the government have voiced concerns about the abuse of the system, but no measures to correct the situation have been taken. A senior judicial director of JKSM gave an interview in which he cited multiple instances of the legal system being manipulated by devious parents to marry off their daughters.[12] He also told journalists that when sex acts have occurred and both sets of parents have consented, the court has “no option but to agree” to the marriage. This is worrying. If the court is not willing to exercise its discretion and decide instead based on proper psychological and expert evaluation on what is best for the child’s future, rather than pressure from the families, the judiciary is essentially playing no discretionary role at all in the protection of the child.

Since reforming the mechanism would require the co-operation of the Shariah court, it is important that this is not viewed as an encroachment into religious law and authority. JKSM itself stated that child marriage is not a ticket for legitimising rape[13] . There is precedence where Islamic authorities have taken a progressive step to regulate marriage and align Islamic family law with health concerns. An example is the pre-marital HIV screening made mandatory by the respective State Religious Departments for all Muslim couples wanting to get married.

To be sure, a number of steps can be easily taken to reform the mechanism. For starters, the Shariah court judge and the Menteri Besar / Chief Minister should be provided with a medical report; a child psychologist evaluation; and a social advocate opinion. The time to grant approval should be lengthened, particularly in cases where the girls are not pregnant. The judge or the Menteri Besar / Chief Minister must, at least, have a single one-on-one session with the child.

The approval process should also be open to objections by the child’s immediate paternal or maternal relatives, a government officer above a certain rank in the Welfare Department, or a social worker with demonstrable grounds for objection. If there is a slightest hint of sexual abuse and unwillingness on the part of the child, the judge or the Menteri Besar / Chief Minister should not hesitate to throw out the application and order a police investigation instead.

In the long run, various state religious councils should convene to discuss raising the minimum age of marriage. Gender sensitisation training should also be considered for judges and Menteri Besar / Chief Minister and their advisors. To pre-empt misunderstanding and resistance, formal and informal sessions should be organised between stakeholders to discuss the proposed reforms and their goals.

Crucially, more Shariah court judges, religious bureaucrats, and (ulama) should speak out so that the efforts to protect underage girls and boys are not twisted to be presented as an attack on religious bodies.

Raising Awareness of Long-term Consequences

For child marriage to be proposed as a solution to pre-marital sex, the cost-benefit analysis would have severely understated the true cost of child marriage and its long-term consequences. There are instances of child marriage ending just after one or two years; victims suffer abuses and harsh treatment by in-laws, and resentment by a husband who had reluctantly married because of family pressure or to escape rape charges. After a divorce, the young girl is often left with a baby. Broader and longer-term effects of a child marriage are often not given due consideration.

Teenage pregnancy, which is used as a justification for child marriage, is also fuelled by two social factors: lack of awareness of contraception, and access to abortion. Family planning services, including counselling, contraceptives, and policy guidelines on abortion should be expanded to include single and underage women / men, not just married couples. Unwanted pregnancy needs to be recognised as a causal factor for child marriage and be tackled accordingly.

Regular publication and breakdown of child marriage statistics, such as their ethnicity, income, geography, and family size are necessary to assist research and enable informative policy-making. Academic institutions and think-tanks in Malaysia should undertake research on the issue.

The following are some potential research questions:

- What are the income levels and education attainment of child marriage practitioners and survivors in Malaysia?

- Does Islam encourage the continuation of child marriage? Is child marriage consistent with Maqasid Shariah and Fiqh? What are the opinions of Islamic scholars and is there a universal consensus?

- How can the government intervene more successfully to curb teenage pregnancies and child marriages (in schools, universities, or through health and education policy; or economic policies and incentives)?

- What is the relationship between child marriage and polygamy? How sustainable are child marriages and what is the long-term impact on the child?

An ethnography study on child marriage practitioners and survivors is sorely needed. Such a study is one of the best methods for understanding a specific group, activity or process.

Preliminary data on Selangor seems to suggest a relationship between the prevalence of child marriage and high instances of polygamy in certain districts. The correlation gets much stronger when the data are expanded to include girls between 16 and 20 years old. It is possible that very young girls are wedded as second, third or fourth wives to much older males practicing polygamy.

Conclusion: Early Intervention is Sorely Needed

Early intervention and child protection education can greatly pre-empt and reduce statutory rape, child sexual abuse, teenage pregnancy and consequentially, child marriage. An intervention programme like No Means No Worldwide has proven to be highly effective in improving attitudes toward women and increasing the likelihood of successful intervention[14].

It provides a dual-gender violence prevention curriculum, where girls are taught how to identify and reject sexual advances, boundary setting, and basic martial arts to fend off attackers. Boys learn to debunk myths perpetuated by rape cultures, and intervene if girls in their surroundings are in danger of becoming victims of sexual crimes. Children should be aware of available help and resources e.g. who to call, what to do in dangerous situations, how to call for help, and how to deal with abuse. This mandatory education in schools, colleges and universities should include information that sex with minors is a criminal offence.

Champions of the cause should engage stakeholders through strategic lobbying; come up with a programme to subsidise and encourage young girl-mothers to re-enter school or the job market; develop a support system for underage parents and child widows; incentivise the public to report child sexual abuse cases; and set up a sex offender registry. Creative policy-making and innovative programmes can be proposed to relevant agencies, such as conditional cash transfers for child widows if they go back to school or gain employment.

The mass media should also invest in investigative journalism. There have been cases where this has brought about real-life changes through the exposing of cases pertaining to the abuse of legal and bureaucratic processes.

Appendices

Table 1: The number of Muslim child marriage applications and approvals by the Shariah court from 2010-2015

Chart 1: Top three states for the highest number of Muslim child marriage applications from 2005-2015.

Chart 2: Non-Muslim child marriage application breakdown according to the Malaysian states from 2000-2014.

**Note: There were no records of their state Terengganu and Labuan for 2,011 cases, meaning this chart only reflects 5,708 out of 7,719 non-Muslim child marriage cases.

[1] Parliamentary reply by Datuk Seri Rohani binti Haji Abdul Karim, Minister of Women, Family and Community Development on 7th March 2016. (No. Soalan: 198).

[2] The figures are quoted by the department’s senior judicial director in an interview with Malay Mail. The numbers are consistent with JKSM statistics submitted for parliamentary reply.

[3] Parliamentary reply by Ministry of Home Affairs. (No. Soalan: 129. Rujukan: 8012).

[4] “Voice and agency: Empowering women and girls for shared prosperity”. World Bank Group. 10 October 2014.

[5] Nguyen, M. C., & Wodon, Q. (2012). Child marriage and education: A major challenge. Study conducted with funding from the Trust Fund for Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development (TFESSD) at the World Bank.

[6] Santhya, K. G., et al., ‘Consent and coercion: Examining unwanted sex among married young women in India’, International Family Planning Perspectives, vol. 33, no. 3, 2007, pp. 124-132.

[7] United Nations Children’s Fund, A statistical snapshot of violence against adolescent girls. UNICEF, New York, 2014.

[8] ICRW, Child marriage and domestic violence: a fact sheet, 2006

[9] “Isu perkahwinan kanak-kanak: kajian dari aspek agama, 167 kesihatan dan psikologi (2014)”, Kompilasi Pandangan Hukum: Muzakarah Jawatankuasa Fatwa Majlis Kebangsaan Bagi Hal Ehwal Ugama Islam Malaysia. Jabatan Kemajuan Islam Malaysia, Putrajaya, Cetakan kelima 2015.

[10] Hadith refers to the reports or accounts of what the Prophet said. There are numerous classifications of Hadith based on the issue of authenticity. The Quran, Sunnah (accounts of what the Prophet did) and Hadith are major sources of guideline for Muslims.

[11] Maqasid Shariah refers to the goals or purposes of the Islamic law. Fiqh refers to Islamic jurisprudence.

[12] Adilah, Anith. “Child marriage used to cover up rape”, Malay Mail Online. 23 April 2016.

[13] Jabatan Kehakiman Syariah Malaysia-JKSM. Facebook post on official account @myJKSM on 15 August 2016.

[14] Migiro, Katy. “Kenyan schoolboys save girls from rape after learning ‘no means no’”, Reuters. 23 March 2015.

Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng Editorial Team: Regina Hoo, Lim Su Lin, Nur Fitriah, Ong Wooi Leng

You might also like:

![Penang’s Aquaculture Industry Holds Great Economic Potential]()

Penang’s Aquaculture Industry Holds Great Economic Potential

![Deconstructing Trump’s Tariffs: The Impact on Penang’s Trade and Economic Resilience]()

Deconstructing Trump’s Tariffs: The Impact on Penang’s Trade and Economic Resilience

![Pluvial Flood Management: Critical Need for Holistic Stormwater Mitigation in Penang]()

Pluvial Flood Management: Critical Need for Holistic Stormwater Mitigation in Penang

![Helping SMEs Rise to Challenges Posed by the Covid-19 Pandemic]()

Helping SMEs Rise to Challenges Posed by the Covid-19 Pandemic

![Counting Candidates: Towards Minimum 30% Women Representation on the Ballot]()

Counting Candidates: Towards Minimum 30% Women Representation on the Ballot