Executive Summary

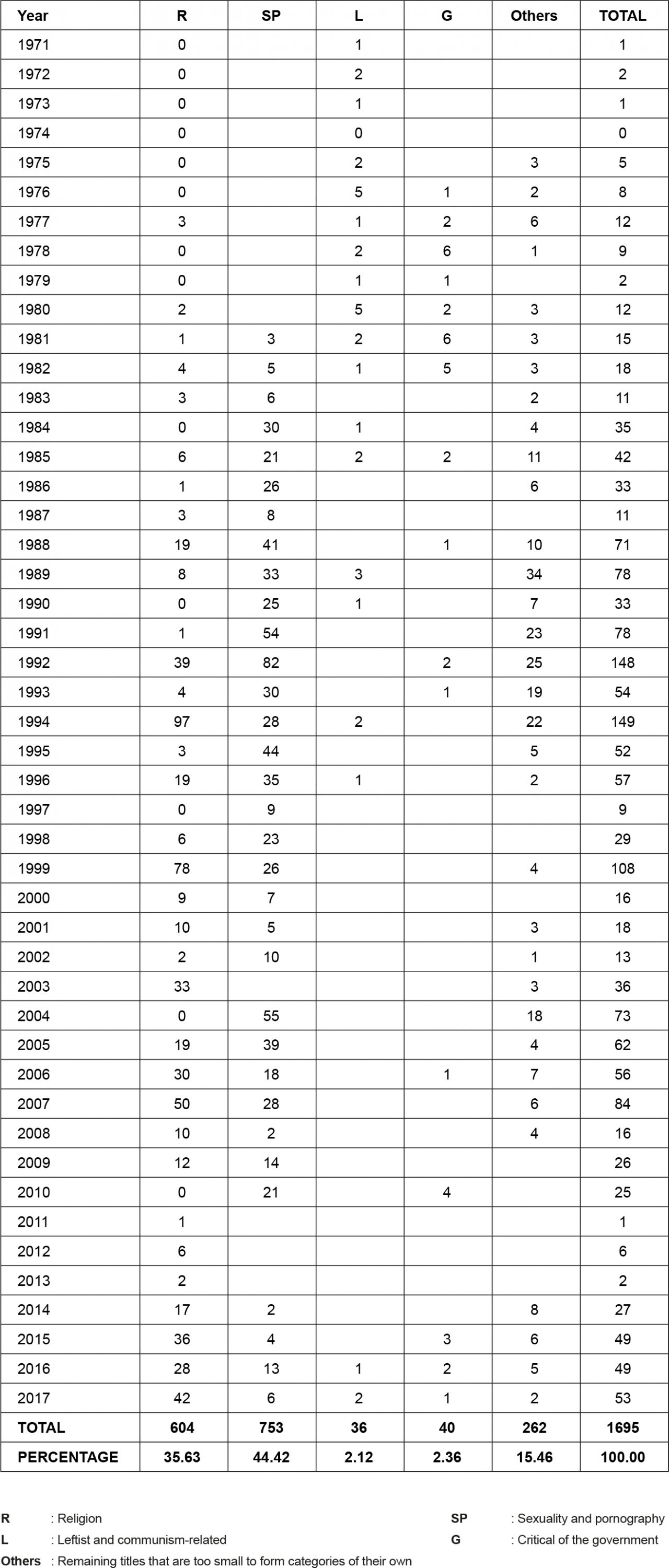

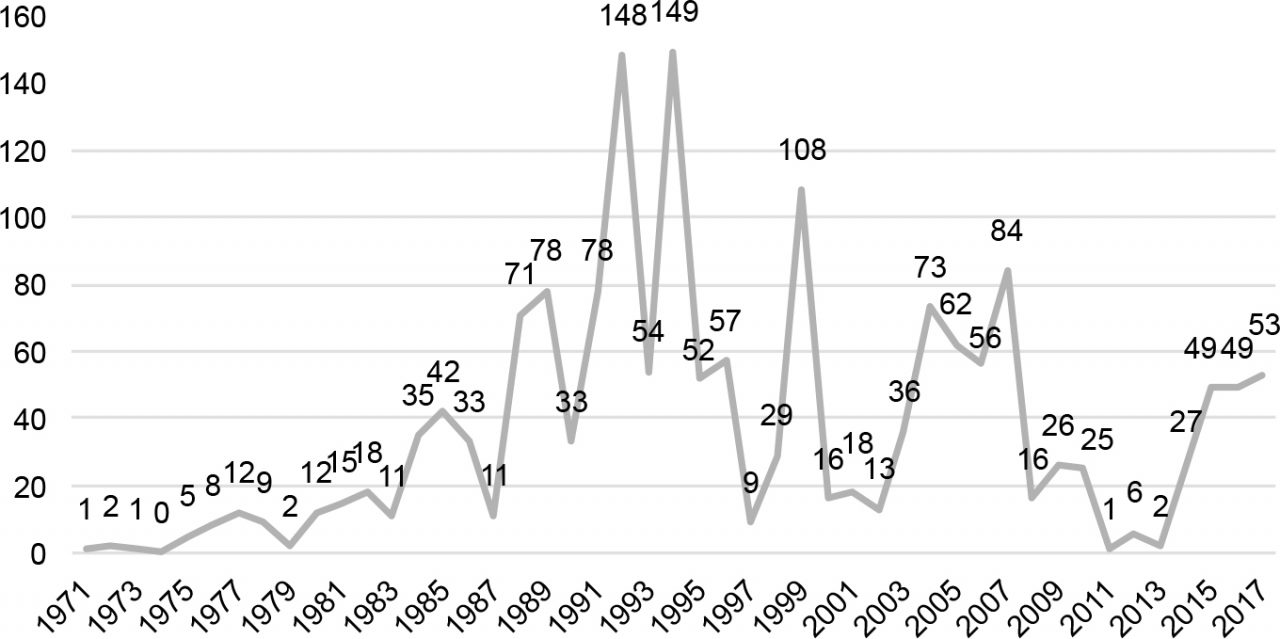

- Book banning in Malaysia is often regarded as arbitrary decisions made in a non-transparent manner. The Home Ministry officially banned a total of 1,695 books between 1971 and 2017, an average of 37 books per year.

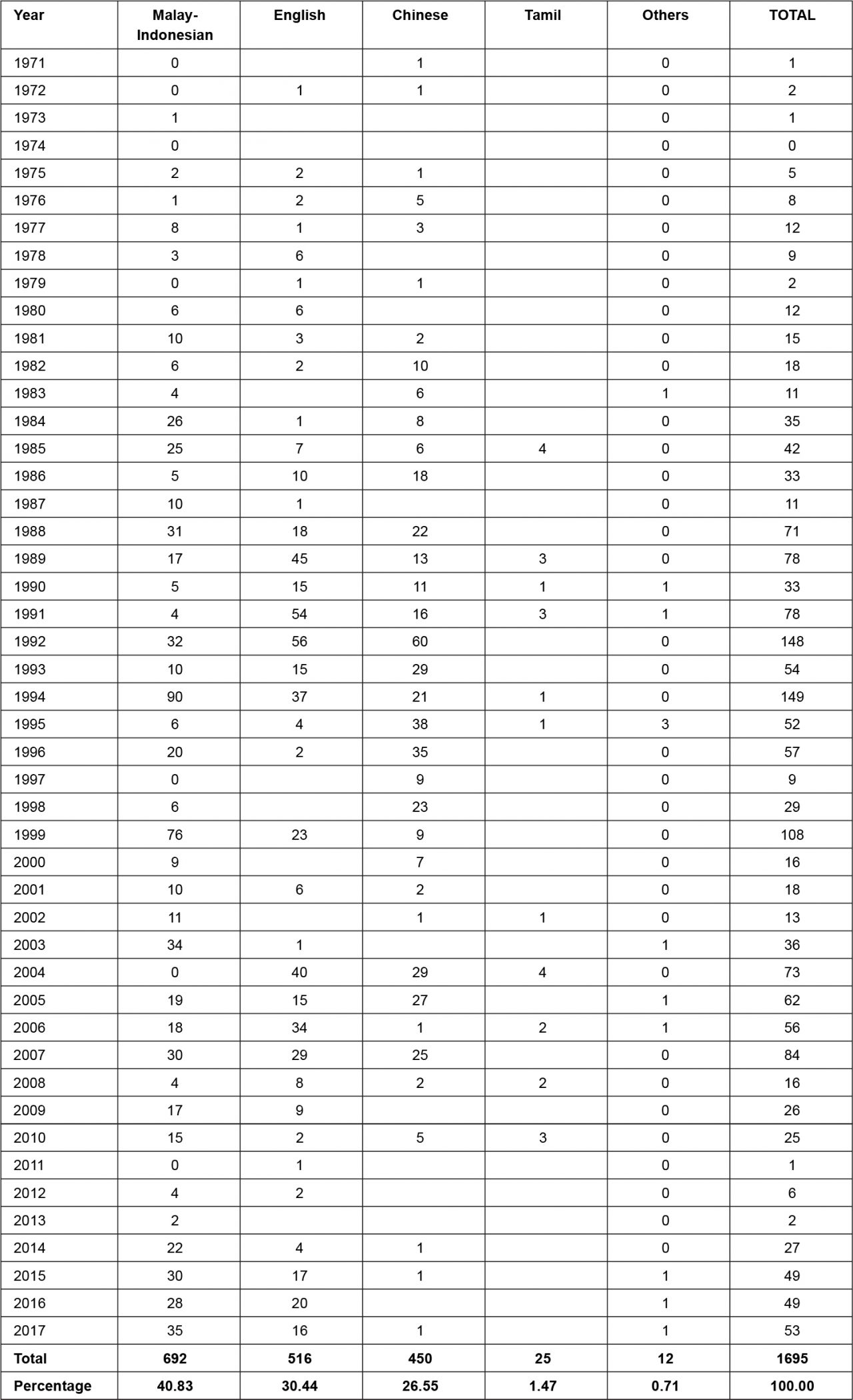

- Books written in both the Malay and Indonesian languages form the majority of banned books at 40.83%. This is followed by English books at 30.44% and Chinese books at 26.55% respectively

- In terms of topical categories, while 1.3% of banned Chinese books and 21.5% of banned English books relate to religion, this figure triples to 61.7% with regards to banned Malay-Indonesian books. This include books that are banned solely in the Malay language, and books that were translated into the Malay language, resulting in the ban of both language versions of the books

- The stricter policing of the Malay language contradicts the attempt to popularise it as a tool for national unity. The desire to control discourse in the Malay language promotes exclusivity, not shared ownership and inclusiveness of the national language

- The language policing has serious implications for academic freedom as books written by non-Muslim scholars and minority Muslim sects on subjects related to comparative religions, Islam and historical Islamic societies have also been banned

Introduction

Under the Printing Presses and Publications Act 1984 (PPPA), the Home Ministry regulates all matters relating to publication including printing, distribution, possession, licensing, and prohibition. The Ministry also has near absolute discretion to ban or limit a publication if the content is deemed prejudicial to public order or morality under the PPPA’s Section 7 “Undesirable Publications”. A case in point is the book Breaking the Silence: Voices of Moderation: Islam in a Constitutional Democracy. Authored by members of the elite Malay lobbying group G25, as well as scholars of constitutional law and social justice, the volume is aimed at promoting moderate Islam. Even so, Home Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi signed the order to ban the book in a gazette circulated on July 27, 2017 on grounds of it arousing public disorder.

Malaysia is no stranger to book banning, and the above mentioned example is by no means the only controversial publication to be prohibited in recent times; the latest being Islam Without Extremes: A Muslim Case for Liberty by the Turkish writer and New York Times columnist Mustafa Akyol, and its Malay translation, as well as Ulama Yang Bukan Pewaris Nabi, a book by Wan Ji Wan Hussin, a popular Muslim preacher and the newly appointed Penang information officer. It is noteworthy that as of October 2017, the number of banned books this year is recorded the highest in a decade.

For the purpose of this brief, the list of banned books from 1971 to present day has been procured from the Home Ministry to analyse and understand the patterns of book banning, as well as their varied negative implications.

Excessive and Vague Powers of the PPPA 1984

The crux of the PPPA 1984 pertains to the control of publications. This can be found in Section 7 of the act:

7. (1) If the Minister is satisfied that any publication contains any article, caricature, photograph, report, notes, writing, sound, music, statement or any other thing which is in any manner prejudicial to or likely to be prejudicial to public order, morality, security, or which is likely to alarm public opinion, or which is or is likely to be contrary to any law or is otherwise prejudicial to or is likely to be prejudicial to public interest or national interest, he may in his absolute discretion by order published in the Gazette prohibit, either absolutely or subject to such conditions as may be prescribed, the printing, importation, production, reproduction, publishing, sale, issue, circulation, distribution or possession of that publication and future publications of the publisher concerned.

Section 8 provides further particulars about related offences:

8. (1) Any person who without lawful excuse is found in possession of any prohibited publication shall be guilty of an offence and shall, on conviction, be liable to a fine not exceeding five thousand ringgit. (2) Any person who prints, imports, produces, reproduces, publishes, sells, issues, circulates, offers for sale, distributes or has in his possession for such purpose any prohibited publication shall be guilty of an offence and shall, on conviction, be liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years or to a fine not exceeding twenty thousand ringgit or to both.

The wide-ranging power of Section 7 has been employed on numerous occasions to justify seemingly arbitrary decisions on book banning. For example, in the gazette serving to notify the public of prohibited publications, book excerpts are not cited by the Ministry to back up its claims of their being prejudicial to public order and morality. Neither is there a transparent process detailing how the decision to ban a book is reached, nor how the publisher can file an appeal to the Ministry. This understandably leads to some bizarre book banning, culminating in mounting resistance. ZI Publications is a case in point. In 2012 the Selangor Islamic Religious Department raided the independent publishing house and seized 180 copies of the Malay translation of Irshad Manji’s Allah, Liberty and Love, five days after the Home Ministry gazetted the ban on both language versions of the book. The raid prompted three different legal responses from the company:

i. Challenge against the Syariah law banning books contrary to Islam;

ii. Challenge against the Home Ministry’s book ban; and

iii. Challenge of the Jabatan Agama Islam Selangor’s (JAIS) raid, seizure, arrest, and prosecution.

The Federal Court dismissed the first challenge by ruling that the state has the power to legislate laws to prevent Islamic deviants. For the second case – ZI Publications Sdn Bhd v. Timbalan Menteri Dalam Negeri & Ors – the High Court quashed the ban on the publication’s Malay translation, a decision upheld by the Court of Appeal, citing the lack of evidence of disturbance to public order:

“If it is true that the book is prejudicial to public order, why was no action taken to ban its English version when it was first circulated? Why was the prohibition (order) made only when it was translated into the national language?”

The case is now pending trial at the Federal Court.

Malay as the Most Policed Language, and Sex and Religion as the Most Policed Topics

A quick study of banned books (mined from the Home Ministry’s database) reveals some interesting points. The first pertains to the language category. Books written in or translated into the Malay language make up the majority (556) of reading materials banned between 1971 and 2017. This is followed by English (516) and Chinese (450) language books respectively.

The language policing pattern is made clearer when two extra factors are added to the equation. As both the Malay and Indonesian languages fundamentally share the same language root, publications in these languages are placed in a category of their own, prompting the increase of banned Malay books to 692, or 40.83%. Additionally, it can be argued that since the mass of the Malaysian population speak and write in the Malay language, it is only natural then to assume that Malay publications would make up the most number of books banned as they are also the most produced and distributed in the country. However, the sequencing factor shows this is not entirely the case. Allah, Liberty and Love was available for a year before the publication was banned following the release of its Malay translation.[1] Mustafa Akyol’s Islam Without Extremes follows a similar trend. Its English version was made available in 2011, and its Malay translation in 2016. However, a ban was gazetted on both language versions of the book early October 2017. Furthermore, though the English version of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species remains available in the market, its Malay translation Asal-Usul Spesies has been taken off shelves. Given the aforementioned factors, it can be inferred that books in the Malay language is subject to stricter language policing.

Secondly, in order for us to further understand the nature of their prohibition, the books that have been banned are topically categorised as follows:

R : Religion

(The category has been further divided into R1 and R2 in the raw data; R1 – books that touch on Islam, its history, societies, political issues etc; R2 – books that deal with other religions e.g. Christianity and Confucianism.)

SP : Sexuality and pornography

L : Leftist and communism-related

G : Critical of the government

Others : Remaining titles that are too small to form categories of their own

Leading the topical categories are books containing elements of sexuality and pornography (44.42% or 753 books), while books on matters of religion make up 35.63% (604 books). It is noteworthy that more than half of these religion-centric books touch on or are related to Islam and Islamic societies (R1).

Breaking the details down further, most books in the R2 category are about Christianity, but written in the Indonesian language. Presumably, they are banned for fear of the books reaching a wide Malay-reading public. A number of books written by non-Muslims about Islam as a subject for comparative history of the world’s religions or issues about political Islam have also been prohibited.

To summarise, the majority of books banned in the Chinese language are SP-related. While books banned in the Malay language have significantly higher R1 and R2 elements.

Thirdly, in terms of time periods, book banning during the 1970s concentrated on left-leaning. Communism-centric publications with references to Mao Zedong, Lenin or the Malayan Communist Party, or even a book by a Vietnamese general detailing the victory of the Vietnam War were banned.

More recently, the trend has shifted towards the policing of books that are believed to be morally and religiously deviant. Interestingly, sexuality and pornography-related books maintain a constant presence throughout.

A cross-examination of both the language and topical categories reflects certain characteristic arrangements. 86.9% of banned Chinese books have sexual and pornographic content while 1.3% have materials that are religiously sensitive. As for banned English books, 21.5% are religion-related. The percentage however triples to 61.7% (427) with regards to banned Malay-Indonesian books. It is worth noting that about a quarter (85) of the books belong in the R2 category, or are reading materials that touch on more than one religion. Most of the banned books in the R2 category are Christianity-related books written in the Indonesian language and imported from Indonesia. Thus, it is not entirely true that the policing of the Malay-Indonesian language books are limited only to the R1 category (Islam), it extends and affects other religions as well.

Table 1: Banned books according to topical categories

Table 2: Banned books according to language categories

Chart 1: Number of books banned annually

The Contradiction and Exclusivity of the National Language

The Malay language is Malaysia’s national language as specified in Article 152 of the Federal Constitution and the National Language Act 1963/67. But the desire to control discourse in the language appears to have curtailed attempts to popularise it as a tool for national unity.

Malay language books in the R2 category are often met with disapproval, if not threatened with limited circulation (allowed only in East Malaysia) or a ban. Malay-written religious content is equally controlled, facilitating the notion of the language as an exclusive space not extended to non-Islamic faiths. Bibles in the Malay-Indonesian and Iban languages, for example, have been banned in Peninsular Malaysia on the implicit assumption that the Malay-Muslim reading public may be tempted to renounce their faith after reading the religious text.

Are the non-Malay-Muslim communities encouraged to practice their religions in the national language, or would that be seen as an attempt to create confusion and as propagation of their religions to the Malay-Muslim community? From the list of banned books, it appears that the fear of causing murtad (apostasy) in the Malay-Muslim community overrides the priority of making the Malay language nationally used and accepted by all Malaysians.

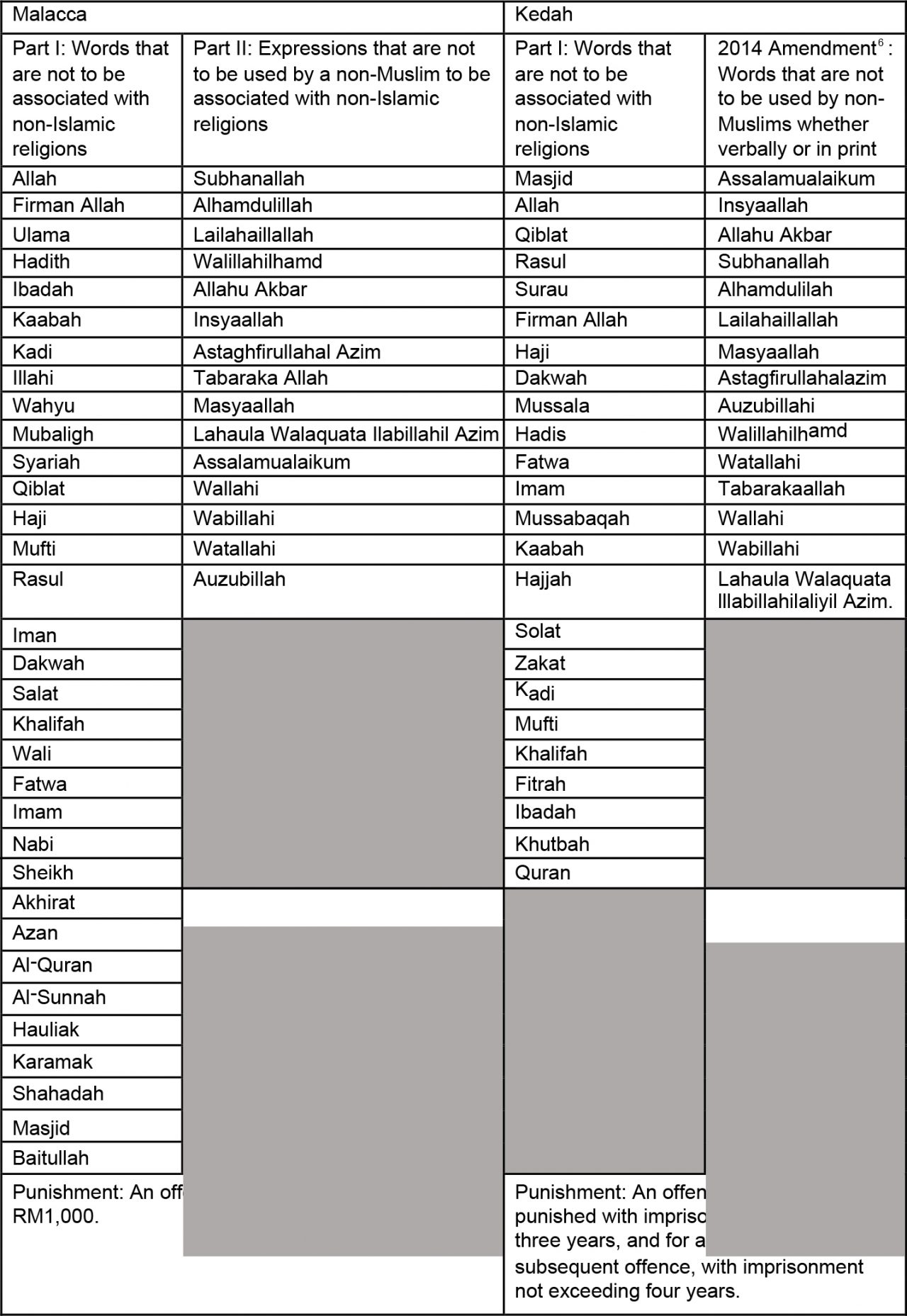

This is further supported by the various Malaysian states’ legal provisions, most significantly the states’ enactments on the Control and Restriction of the Propagation of Non-Islamic Religions that prohibit non-Muslims from using certain words and expressions deemed to be of Islamic origin.[2] For example, the Kedah enactment (Section 9) reads:

(1) A person commits an offence if he, in any published writing, or in any public speech or statement, or in any speech or statement addressed to an organised gathering of persons, or in any speech or statement which is published or broadcast and which at the time of its making he knew or ought reasonably to have known would be published or broadcast, uses any of the words listed in the Schedule, or any of its derivatives or variations, to express or describe any fact, belief, idea, concept, act, activity, matter, or thing of or pertaining to any non-Islamic religion

(2) Any person who commits an offence under subsection (1) shall, on conviction, be punished with imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years, and for a second or subsequent offence, shall be punished with imprisonment for a term not exceeding four years.[3]

This raises serious issues concerning the exclusive control of the list of words and their implications on the ability to practice non-Islamic faiths in the national language.[4] Prophets and apostles are key figures in Abrahamic religions, but there are state enactments in place that can lead to imprisonment of non-Muslims for uttering or writing the equivalent of those words in the Malay language. Consequently, it restricts the ability to practice other religions in the Malay language because one could utter the words “prophets” and “apostles”, but not their Malay equivalents nabi and rasul. [5]

The stringent language control also has the unintended consequence of making the national language less competitive. The transmission of knowledge and the development of public discourses are limited by the lack of vocabulary and reading materials in the Malay language due to the policing and restrictions imposed. For example, The Origin of Species is only available to English-speaking readers, making it difficult for those who are solely literate in the Malay language to grasp the book’s key concepts and terminologies.

Table 3: Examples of selected prohibited words for non-Muslims in Malacca and Kedah

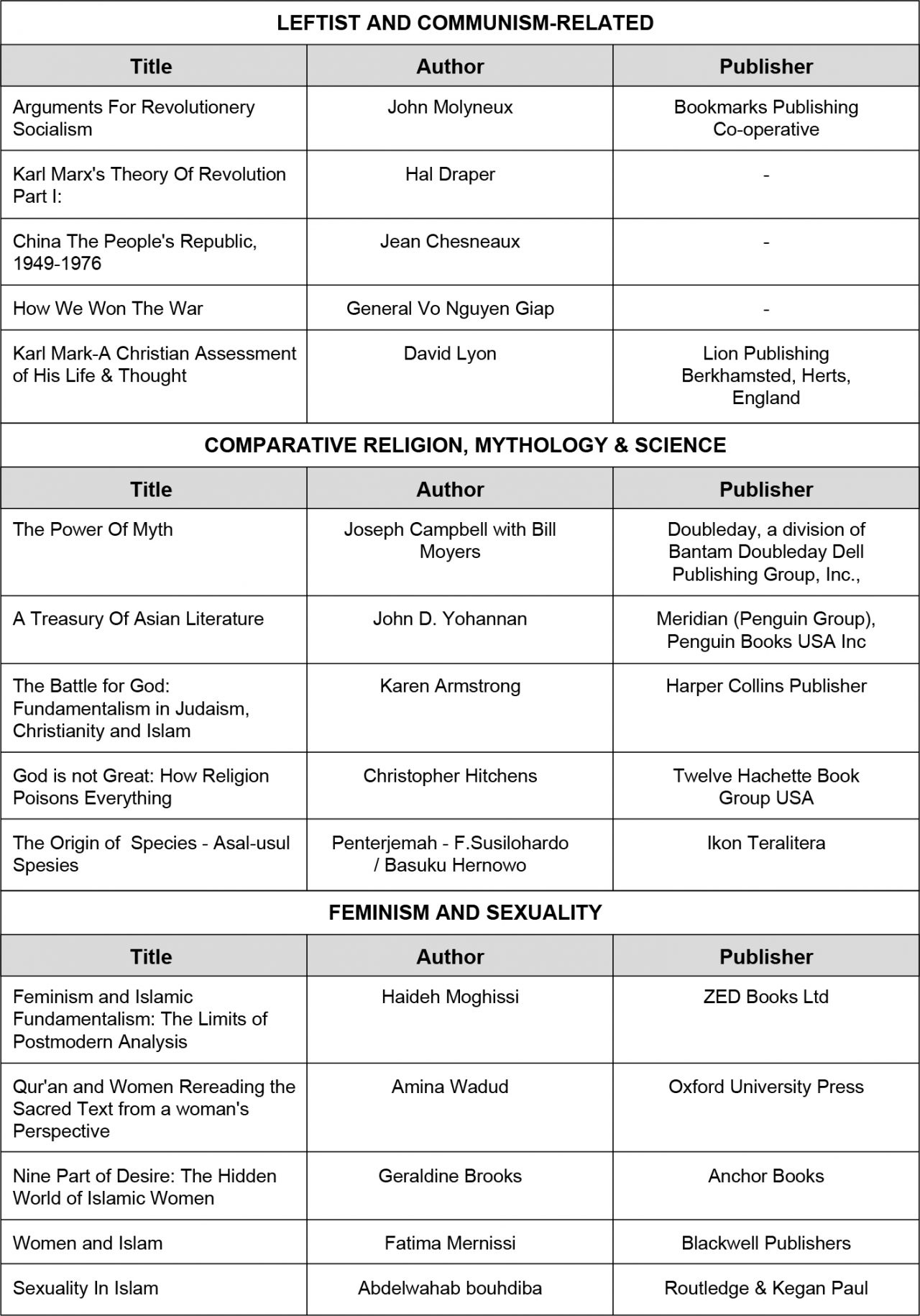

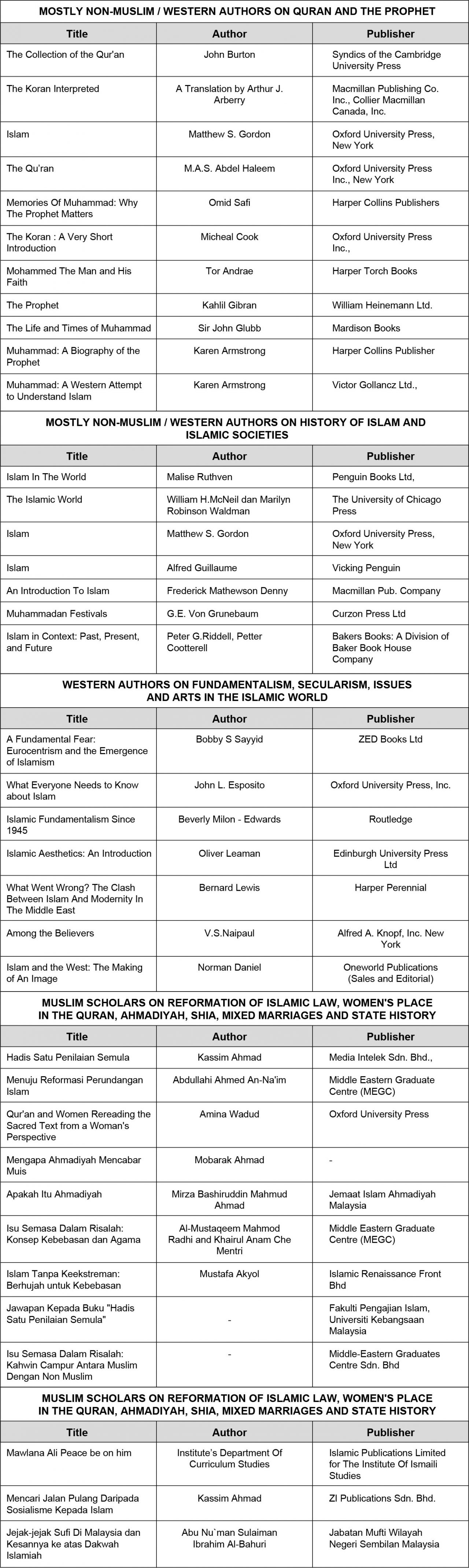

A number of books written by non-Muslims on comparative religions, and on subjects related to Islam and historical Islamic societies have also been banned. (Table 4 shows the list of notable academic books banned by the Home Ministry). This begs the question: Are the authors’ religions a contributing factor to the ban? If so, that would be tantamount to religious discrimination; not to mention a curtailing of academic freedom.

Clearly, the bans are not limited to only Western or non-Muslim academics, but also minority Muslim sect scholars with books in the R1 category. This includes publications and academics writing on secularism (Menuju Reformasi Perundangan Islam by Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na’im; its Malay translation is banned), women in Islam (Qur’an and Woman: Rereading the Sacred Text from a Woman’s Perspective by Amina Wadud), extremism within Muslim societies (Islam Without Extremes by Mustafa Akyol), Al-Arqam (nearly all titles published by al-Arqam-affiliated publishers), Ahmadiyah (Mengapa Ahmadiyah Mencabar Muis by Mobarak Ahmad; Apakah Itu Ahmadiyah published by Jemaat Ahmadiyah Muslim Malaysia), freedom of religion (Isu Semasa Dalam Risalah: Konsep Kebebasan dan Agama by Al-Mustaqeem Mahmod Radhi and Khairul Anam Che Mentri), and seven books by local academic and novelist Mohd Faizal Musa, popularly known as Faisal Tehrani.

Table 4: Selected banned academic books found in the Home Ministry’s list

Table 5: Selected academic books that are banned possibly due to the religion, outsider status, and minority sects of the authors

Conclusion

The process through which the Home Ministry decides on banning any particular book should be made transparent and credible. This can be easily achieved by citing any book excerpts that may potentially harm public order or morality. An avenue for challenge should also be made available. Significant development with regards to whether the freedom of expression is stifled by a book ban now depends on the Federal Court’s hearing of ZI Publications Sdn Bhd v. Timbalan Menteri Dalam Negeri & Ors.

It is also crucial to ask whether it is realistic for the Home Ministry to conduct language policing and book banning in this day and age. Book banning will only increase publicity for the book; not to mention there are various possibilities to circumvent the ban. One can easily download it online, or find the book in another version or published by another publisher (for example, a Malay translation of Charles Darwin’s book Asal-Usul Spesies was banned, but there are still alternate versions such as Teori Evolusi Manusia readily available). Unless the Home Ministry is planning to be on constant look out for other book versions and translations, it is safe to conclude that the book ban is not only ineffective, but also counter-productive.

Managing Editor: Ooi Kee Beng Editorial Team: Regina Hoo, Lim Su Lin, Nur Fitriah, Ong Wooi Leng

[1] ZI Publications Sdn Bhd currently have three civil cases: challenge against Shariah law banning books contrary to Islamic law, challenge against Home Ministry’s book ban, and challenge of JAIS’s raid. http://www.themalaymailonline.com/malaysia/article/lawyer-hearing-of-ezra-zaids-challenge-of-jais-arrest-on-aug-28 #LoXD1BbBlrgg5oTo.97

[2] All states except Penang, Sarawak, Sabah and federal territories have such an enactment. However, there are provisions in the other existing state enactments that allow for or/and can lead to similar prohibitions.

[3] Enactment No. 11 of 1988, Control and Restriction of the Propagation of Non-Islamic Religions Enactment 1988. Part II- Offences, Section 9. Different states have different degree of punishment (from a few thousand Ringgit fines to as heavy as multiple years of imprisonment) and variety of prohibited words.

[4] This observation is first made in: Wong, Chin-Huat, “If Allah is Islam-exclusive, can Bahasa Melayu be national?” Hornbill Unleased. 29 December 2013.

[5] For more on legislations pertaining to restriction of propagation of non-Islamic religions, see Roger Tan, “Religion and the law”, The Star. 12 January 2014. And “Legal Provisions and Restrictions on the Propagation of Non-Islamic Religions among Muslims in Malaysia”. Kajian Malaysia, Vol. 31, No.2, 2013, 1-18.

[6] “Kedah larang bukan Islam guna 15 perkataan”, Sinar Harian. 23 November 2014. In the same report, the State Exco in charge of Religious Affairs said, ““Contohnya, ada pemimpin bukan Islam ucap Assalamualaikum sebelum ceramah umum, kita boleh dakwa. Kita akan bertindak tegas untuk elak perkataan khusus Islam digunakan sewenangnya oleh bukan Islam.”

You might also like:

![Eradicating Child Marriages in Southeast Asia: Protecting Children, Challenging Cultural Exceptional...]()

Eradicating Child Marriages in Southeast Asia: Protecting Children, Challenging Cultural Exceptional...

![Podcasts: Challenges and Opportunities for Media Practitioners, Policymakers and Individuals]()

Podcasts: Challenges and Opportunities for Media Practitioners, Policymakers and Individuals

![Reducing Moral Hazards in Malaysia’s Public Healthcare System]()

Reducing Moral Hazards in Malaysia’s Public Healthcare System

![Key Changes to Development Expenditure in Malaysia’s Budget 2019]()

Key Changes to Development Expenditure in Malaysia’s Budget 2019

![Installing a Facial Recognition System at Penang Airport: A Necessary Step to Ease Travel Protocols]()

Installing a Facial Recognition System at Penang Airport: A Necessary Step to Ease Travel Protocols