Media Statement by Darshan Joshi, Research Analyst at the Penang Institute, on 19 October 2018

Earlier this month, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published a special report [1] titled ‘Global Warming of 1.5˚C’. This report highlights the dangers of a 1.5˚C increase in the Earth’s average surface temperature over preindustrial times. At present, we have already banked in 1˚C (and possibly up to 1.2˚C) of this rise, and the dangers of further increases are well-‐‑documented – not just in this particular report, but many others in the literature. A brief summary of some of the expected damages of climate change intensification can be found in an article [2] I authored back in January.

The scientific consensus over the dangers of a 1.5˚C rise in temperatures makes for grim reading, let alone that of a 2˚C increase. The extent of the policy commitments required to stave off the worst of climate change is even more sobering; consider, for instance, that even a global fulfilment of the nationally-determined emissions reductions pledges as per the Paris Accord would still likely see temperatures rise by between 2.6 and 3.2˚C, at best [3]. In other words, what we are willing to do, for the time being, is still far from enough to limit the sort of dangerous warming that will almost certainly have drastically negative economic impacts on both our country and planet. We need to do more.

As things stand, Malaysia still lacks strong policies to facilitate the transition to a zero-‐‑carbon economy. In the following paragraphs, I focus on two key areas responsible for over half of our emissions, namely electricity generation and transport; briefly discuss the steps that have been taken to mitigate emissions within these sectors thus far; and offer suggestions to significantly strengthen our climate change policies moving forward.

Electricity Generation

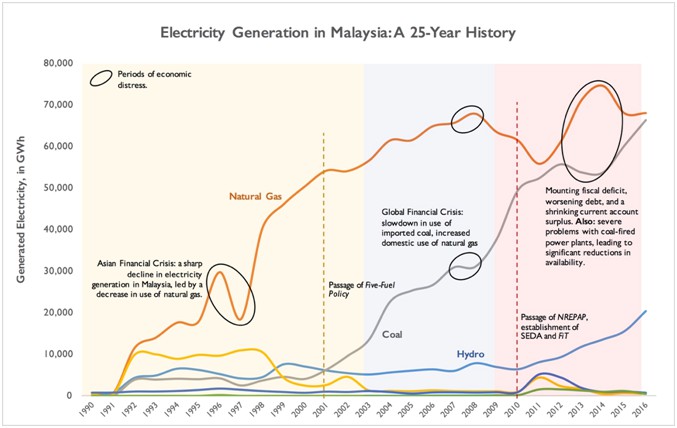

Electricity generation contributes most to national greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Between 1990 and

2011, emissions from this sector increased by over 465% [4], from 20.14 MtCO2e to 113.87 MtCO2e. To put this growth rate into perspective, fugitive emissions from oil and gas operations, the second-fastest growing source of emissions over this time period, saw a growth rate of ‘just’ 349.6%.

In the 1990s, the rise in emissions from electricity generation was the result of fast-‐‑growing electricity demand being met by an increase in our consumption of natural gas. Since the early 2000s, growth in electricity demand has largely slowed, but natural gas has been phased out in favour of coal. The share of coal in electricity generation has, as a result, risen from just 6.3% [5] at the turn of the millennium, to a shocking current average of 57.4% between April 1 and October 15 [6]. If we’re looking for the culprit behind the startling rise in electricity sector emissions over the past two decades, look no further than coal. We need to kick this habit.

Running concurrently to these twin developments – increasing electricity sector emissions and a growing

reliance on coal – has been seemingly contradictory rhetoric around sustainability and renewable energy

(RE). The 2001 Five Fuels Policy introduced RE as the nation’s ‘fifth fuel’, after oil, hydro, natural gas, and coal; that same year, the Small Renewable Energy Program (SREP) was launched. Unfortunately, both policy and programme failed to achieve much of note. By the end of the SREP in 2009, RE contributed a mere 0.2% to Malaysia’s electricity generation capacity of almost 22,000MW [7].

In 2010, the National Renewable Energy Policy and Action Plan was launched, and the Sustainable Energy Development Authority (SEDA) was established, alongside the feed-in tariff (FiT) mechanism and the Renewable Energy Fund (REF). The FiT was expected to spur a wider adoption of clean energy in Malaysia, and an RE capacity target of 975MW was set for 2015. But by the time 2015 arrived, the FiT had succeeded in reaching only half of this target. A key reason for this failing was a lack of funding for the FiT mechanism [7]. Had SEDA received a greater fiscal allocation and was able to approve more applications for the highly-demanded solar PV FiT quota, we would have stood a better chance of reaching our RE targets.

In 2016, we had another policy shift, which saw solar PV being phased out of the FiT, in favour of net energy metering (NEM). The outcomes of this policy, however, have been even more disappointing, due largely to its very weak incentivisation structure. As of June, NEM had contributed an additional 13.56MW to Malaysia’s electricity generation capacity, a laughable amount– if climate change was anything to joke about. The announcement by YB Yeo Bee Yin on 18 October [8] that NEM will be favourably tweaked, and that Malaysia will press on with a third auction for large-scale solar plants, is at least welcome news.

Over the span of almost two and a half decades, Malaysia has invested billions of ringgit on renewable energy policies, yet all we have to show for this massive expenditure is an RE share of electricity generation of under 3%. This paltry figure is far from good enough, and it is difficult to see how Malaysia is making significant progress with regard to meeting the pledges it made to the UNFCCC in 2015 [9].

Click here to enlarge. Note: the green line at the very bottom represents all renewables.

Transport

Transport is the next biggest contributor to GHG emissions in Malaysia, accounting for 65.5 MtCO2e in 2016 [10], for a share of total emissions of 20.7%. Much of this is down to increased motorisation rates [11]. Inexpensive locally-produced cars and inadequate public transportation networks are also to blame, as is an expensive and inefficient subsidy for petrol. While it deserves a separate argument of its own, I strongly believe that the petrol subsidy should be re-examined by the relevant Ministries, and a roadmap to its removal should be drawn up. Given that we currently sit at the dawn of the electric vehicle (EV) age, the Pakatan Harapan government has reason to muster up the political courage to disincentivise the consumption of petrol – and cut distortionary spending.

There are two significant yet feasible avenues through which transport-related emissions can be curtailed: first, through improvements to the accessibility, reach, and use, of public transport options across Malaysia, and, second, through the mass-adoption of electric vehicles (EVs). Emissions per passenger-kilometre are lowest with public transport (and, well, walking or cycling) [12]. More densely populated areas of Malaysia need to be well-serviced with buses and trains. We must continue to invest smartly in expanding public transport networks across densely-populated regions of the country, and this includes last-mile connectivity. EVs, meanwhile, have the potential to drastically mitigate personal transport-related emissions, but under specific conditions.

In a recent paper [13], I have argued that under our current, fossil fuel-reliant electricity generation mix, EVs are on average considerably more polluting than conventional petrol-powered vehicles. It is only as the share of RE in electricity generation exceeds 30% that EVs are cleaner. This is another reason for us to push strongly for a greater share of clean energy in power generation; the environmental benefits will spill over to other sectors, and contribute greatly to a greening of the wider Malaysian economy.

With effective policies that emphasise RE and public transport, and set the foundations for a medium- to long-run electrification of Malaysia’s vehicle fleet, our country would be in a strong position to significantly mitigate the climate impacts of two key sectors that are consistently responsible for over half of our total GHG emissions.

One Policy to Rule Them All: A Tax on Carbon

Sector-specific action aside, the latest IPCC report’s rallying cry to policymakers is exactly the same one they’ve had since the Panel was formed in 1988: to put a price on carbon. Back in 1997, over 2,500 economists, including eight Nobel laureates, attached their names to the ‘Economists’ Statement on Climate Change’, suggesting that “the most efficient approach to slowing climate change is through market-based policies […] nations can most efficiently implement their climate policies through market mechanisms, such as carbon taxes […] revenues generated from such policies can effectively be used to reduce the deficit or to lower existing taxes” [14]. Economists do not generally agree on very much, yet with a carbon tax, there is an almost perfect consensus.

Carbon taxes are beneficial in numerous ways. Most importantly, they address the negative externality of carbon emissions, by forcing polluters to acknowledge the environmental costs of their actions. In addition to causing emissions to re-optimise at a lower level, a carbon tax levels the playing field between fossil fuels and RE. A virtuous cycle then plays out: as RE becomes relatively cheaper, the industry will see greater investment channelled toward it, driving costs down even further. Revenues from a carbon tax can in turn be utilised in several ways: providing regular funding for climate change mitigation and adaptation policies (such as the aforementioned FiT and NEM mechanisms); alleviating the burdens of Malaysia’s current budgetary crisis and improving the ability of the government to invest in public infrastructure as well as progressive policies and programs which may benefit the Rakyat – particularly those in the B40 group.

With just one policy, we can achieve wins for the environment, the Rakyat, government coffers and economy efficiency. The argument for a tax on carbon is consequently a strong one; as citizens, we need to fight for its implementation, for the sake of our medium- to long-run welfare, and to put to end to what is essentially a subsidy to those who are polluting our country and contributing most to climate change.

Such a tax should cover electricity generation to start with; if all the CO2e emitted from coal and natural gas plants in 2016 was taxed at RM30/ton, resultant government revenue would have amounted to just under RM2.63bn for that year alone [15], [16]. The societal and environmental benefits would be larger still. With time, it would be prudent to include the transport and heavy industry sectors within the scope of a carbon tax, as we push further towards the decarbonisation of the Malaysian economy.

The evidence is mounting that unmitigated climate change will cause devastating damage across the global economy. Yes, climate action is costly in the short-run. But climate inaction will very likely be costlier still, in the medium- to long-run. A myopic attitude to the issue of climate change will hurt the future of human civilisation dearly. We need to act, and we need to act strongly.

List of References

[1] http://www.ipcc.ch/report/sr15/

[2] https://www.themalaysianinsight.com/s/33573/

[3] https://climateactiontracker.org/global/temperatures/

[4] https://unfccc.int/files/national_reports/non-annex_i_parties/biennial_update_reports/application/pdf/malbur1.pdf

[5] https://www.st.gov.my/contents/files/download/116/Malaysia_Energy_Statistics_Handbook_2017.pdf

[6] https://www.singlebuyer.com.my/resources-dispatch-schedule-aggregate-monthly.php

[7] https://penanginstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Evaluating-the-Performance-of-SEDA-and-RE-Policy-in-Malaysia_PI_Darshan_5-June-2018.pdf

[8] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6qMyXGAk5fY

[9] http://www4.unfccc.int/ndcregistry/PublishedDocuments/Malaysia%20First/INDC%20Malaysia%20Final%2027%20November%202015%20Revised%20Final%20UNFCCC.pdf

[10] https://www.climatewatchdata.org/countries/MYS

[11] http://www.oica.net/wp-content/uploads//Total_in-use-All-Vehicles.pdf

[12] https://www.eea.europa.eu/media/infographics/carbon-dioxide-emissions-from-passenger-transport/view

[13] https://penanginstitute.org/programmes/penang-institute-in-kuala-lumpur/electric-vehicles-in-malaysia-hold-your-horsepower/

[14] http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.131.3255&rep=rep1&type=pdf

[15] Author’s calculations, assuming 54.3MtCO2e in emissions from coal, and 33.3MtCO2e in emissions from natural gas power plants, in 2016. Data for electricity generation in 2016 is derived from [5], while those for the life-cycle CO2e emissions by fuel source are derived from [16].

[16] https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/wg3/ipcc_wg3_ar5_annex-iii.pdf