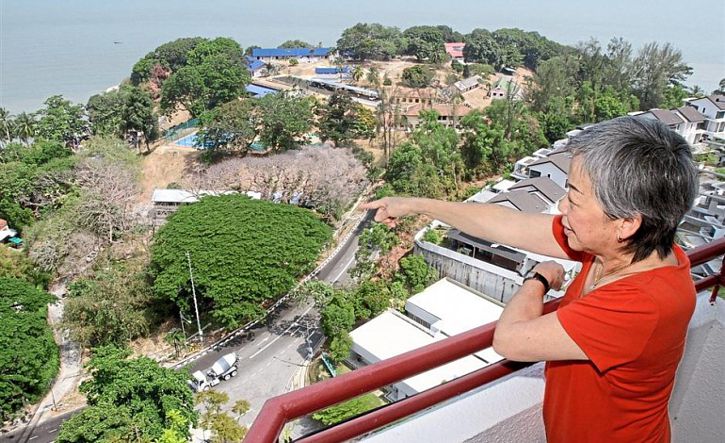

Sri Sayang apartment resident Siau Bloomfield pointing to the narrow plot between the Batu Ferringhi Army Camp (right) and Rasa Sayang Resort (left, not in picture) where a 15-storey hotel is being planned. Residents here are also upset that such a development can be allowed. Photo: The Star/Chan Boon Kai

First, the shocks from the explosions are felt. Then the people brace themselves for the gravel that rain down on their houses and pray that the blast debris would not include rocks the size of a fist smashing their roof tiles again.

This is what residents in Paya Terubong on Penang island face. Of the 530,000 people living on the island’s North-East District (2012 census), a whopping 270,000 are estimated to be packed into this working-class suburb.

Last year, terraced homeowners in one of Paya Terubong’s numerous residential estates were dismayed to hear the news that four apartment towers – three of them 47 storeys and one 41 storeys – have been approved for construction on a hillside just 50m behind their backyard.

Debris from the rock blasting so close to them has damaged roofs, windows and cars. With the hill cutting, heavy rains brought mud floods.

The developer wants to build 1,624 units and 320 accompanying shoplots. That would see an influx of at least 1,000 more cars and 7,000-10,000 new residents into the neighbourhood.

“When we moved in six years ago, we were told that six-storey townhouses would be built on the hill behind our houses. We didn’t have a problem with that. I don’t understand how the developer succeeded in changing the townhouse plan to four apartment towers,” says resident Dr Ti Lian Geh, who together with his neighbours has filed an appeal with the Planning Appeals Board to stop the development.

Filepic of tarpaulin sheets laid out on hill slope cutting works for a high-rise development in Paya Terubung last year, to prevent soil erosion during the rain. The nearby residents have appealed to the authorities to stop the project which they claim is not in the development plan for the neighbourhood. Photo: The Star/Gary Chen

He said that in Paya Terubong and also Bandar Baru Air Itam, it was common for many high-rise dwellers to skimp on the second parking lot.

“Residents will park their second cars along the access roads at night. Our street is not broad enough for the stress. The bottleneck will be unimaginable,” Dr Ti says.

Over at Batu Ferringhi, another developer is also springing a surprise on residents.

On a slip of land less than 0.5ha wedged between Shangri-La’s Rasa Sayang Resort and Spa and the Batu Ferringhi Army Camp, there are plans to build a 15-storey three-star hotel.

If it materialises, hotel guests on the top floor might get an unobstructed view of the army camp activities (cue alarm bells). Batu Ferringhi is also pressured by horrendous weekend gridlock traffic due to the narrow, winding access road from the city and its long stretch lined with resorts and entertainment outlets.

The Town and Country Planning Department did not approve it, but the developer would not be discouraged and has recently applied once more for consent.

It is a blessing that in planning law, adjacent residents are allowed to object, just as in the case of the Paya Terubong towers. So the neighbourhood has launched their objections against the developer’s re-submission on top of holding peaceful demonstrations along the roadside.

Like many old places, Penang island grew organically, says State Local Government Committee chairman Chow Kon Yeow.

Chow highlights a legend of how Captain Francis Light got Penang’s development off the ground quickly. On arrival, the British navyman was said to have loaded his ships’ cannons with coins and, getting his labourers to watch, fired them into the jungle. He then armed them with machetes and told them they could keep any coins they found. In short order, he had cleared the jungle for George Town.

Chow says Penang did not have a master plan and early pioneers built whatever was expedient on an ad hoc basis.

Penang island did not have a master plan from the start and development has been ad hoc, says State Executive Councillor Chow Kon Yeow.

Penang island did not have a master plan from the start and development has been ad hoc, says State Executive Councillor Chow Kon Yeow.

“People in the 1800s had no idea that a few generations later, there would be cars going at speeds they cannot imagine. So even when a proper grid system of roads came up later in George Town, they were meant for bullock carts,” Chow says.

Those familiar with Penang’s progress know that Chow generally has many headaches since his portfolio includes local government and traffic.

While Light equipped labourers with machetes, Chow had to equip Penang Island City Council enforcement officers with sledgehammers.

Hotels have been sprouting like mushroom in George Town in the last couple of years and some of them are built in prewar shoplots.

Without proper provisions for matters like fire hazard control, sewage and parking, these illegal hotels are disasters waiting to happen. Many even renovated the prewar shoplots to partition floors into as many rooms as possible, to the point of making the premises unsafe.

The entrepreneurs refused to comply or shut down, so city council demolition teams had to go in and demolish their premises.

With the limited land space and historical baggage that stunt planning and development, George Town can be said to be bursting at the seams.

Small wonder then that urban planners in the state are gleeful over what will potentially happen in the south of Penang island.

The reclamation of two new islands totalling 1,497ha (about 5% the size of Penang island) is being planned off the southern coast.

This real estate will be used to financed the RM27bil Penang Transport Master Plan, a public transportation upgrade down to the last mile that is being touted as a game changer in Penang’s quest to stay on top of its game as an international magnet.

Glowing accounts of project components such as light rail transits and monorails aside, urban planners have their sights trained on these two new islands.

“We finally have the chance in Penang to build townships meant for people on those islands,” says Penang Institute head of urban studies Stuart Macdonald.

Penang Institute is a public advisory body and think tank of the state government that constantly studies the state’s history, economics, urban planning, political and social challenges.

International urban planning, Macdonald says, has changed in the last 40 years and planners have realised that having dedicated zones for residential, commercial and industrial uses create more problems than they solve.

Spread out this way, he says, such an environment makes life less healthy and more expensive for people.

“That’s not the way people live. In a town for people to live and work, the scale must be smaller. Distances between home and work must be ‘walkable’.

“Those two new islands present the chance for Penang to find a new level of ‘liveability’,” says Macdonald.

Source: http://www.star2.com/living/2016/04/14/too-close-for-comfort-for-penang-folks/