Press Release by the Penang Institute in Kuala Lumpur on the 2nd of January, 2018

Health provider workforce shortages, expensive private treatment charges and stigmatization of mental illness signpost troubling barriers in the provision of access to mental health services in Malaysia

KUALA LUMPUR: Despite the advances made in mental health policymaking over the years, several substantial barriers to treatment for the mentally ill in Malaysia remain, according to recent findings released by Penang Institute [1].

The report, released on 2nd January, highlighted key issues weakening the accessibility of mental health services in the wider community. These included shortages of key mental health specialists in public healthcare, prohibitively expensive treatment charges in the private sector that are exacerbated by a lack of private health insurance coverage for mental health and social stigma that discourages the mentally ill from actively seeking treatment.

1. Mental Health Workforce Shortages

(i) Psychiatrists

From a health provider standpoint, the effectiveness of mental health services in government health care is weakened by workforce undersupply and maldistribution issues.

Although the number of psychiatrists in Malaysia has increased over time, their numbers in public healthcare settings remain significantly lower than what is required for population needs, as reflected in the trends of change in national and state-level doctor-to-population ratios in recent years.

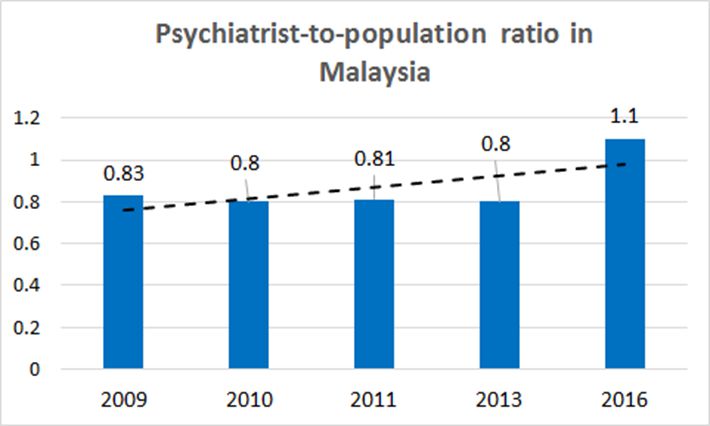

Figure 1: National Psychiatrist-to-Population Ratios in Malaysia from 2009 to 2016

Sources: National Healthcare Establishment and Workforce Statistics, NHEWS report, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012-2013; Department of Statistics, Specialty & Subspecialty Framework for Ministry of Health Hospitals Under the 11th Malaysia Plan

Between 2009 and 2013, the number of psychiatrists per 100,000 population in Malaysia hovered at the 0.8 mark, reflecting a minimal increase in the actual numbers of psychiatrists (merely 9 new specialists entered the workforce in this period).

In order to evaluate the significance of this ratio, the report applied a benchmark range of 0.5-6.6 psychiatrists per population, which had been derived from the findings of the WHO 2014 Mental Health Atlas report [3]. In the WHO report, sampled low-and lower-middle income countries were found to have a median number of less than 0.5 per 100,000 psychiatrists per 100,000 population whilst high-income countries had 6.6 psychiatrists per 100,000 population as the median figure.

As Malaysia was classified as an upper middle-income country, together with countries like China, Thailand and Brazil, its psychiatrist per population ratio should ideally fall within the mid-point of the ‘benchmark’ range, i.e. 3.55. However, as shown in Figure 1, between 2009 and 2013, Malaysia’s ratio was far from reaching this target.

From 2013 to 2016, Malaysia’s psychiatrist per population rate rose to 1.1 due to an augmented increase in manpower, where 118 new specialists entered the workforce during the period [2]. While the absolute increase is encouraging, psychiatrist-to-population ratios still fell short of meeting the 3.55 figure that should theoretically be expected of an upper middle-income country, based on the WHO benchmark range.

The minimal increase in psychiatrist-to-population ratios over the years suggests that there has been, and continues to be, a very limited availability of these specialists to serve the population in need. The state breakdown of psychiatrists provides a more detailed picture of how this shortage affects access to mental health care in the localities.

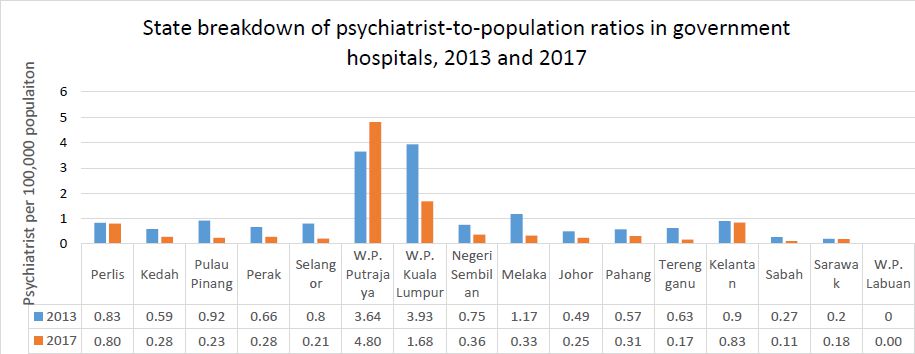

Figure 2: State psychiatrist-to-population ratios in government hospitals for years 2013 and 2017

Sources: NHEWS report 2012-2013; National Specialist Register; Malaysian Medical Council practitioners’ registry; Department of Statistics; author’s own calculations.

Comparing psychiatrist-to-population ratios in government hospitals for the years 2013 and 2017, certain key patterns over the 5-year period were observed.

Firstly, psychiatrist-to-population ratios in all states except WP Putrajaya [4] had shrunk from 2013 to 2017. The extent of this ‘shrinking’ in ratios varied from state to state. Kuala Lumpur experienced the greatest reduction in psychiatrist-to-population ratios, going from 3.93 to 1.68 psychiatrists per 100,000 population from 2013 to 2017. This was reflected in a drop in actual numbers of these mental health providers in the state’s government hospitals (from 54 in 2013 to 30 in 2017).

Meanwhile, states like Johor and Pahang experienced relatively smaller reductions in psychiatrist-to-population ratios, although it should be remembered that in 2013, these same states also had much smaller numbers of psychiatrists to begin with compared to Kuala Lumpur (15 psychiatrists in Johor, 9 in Pahang).

From 2013 to 2017, certain states had maintained the same number of psychiatrists, but growth in population figures caused psychiatrist-to-population ratios to dip. For example, the number of psychiatrists in Perlis (2) and Kelantan (15) remained unchanged between 2013 and 2017, however population figures had increased from 241,400 to 251,000 in Perlis and 1,665,900 to 1,797,200 in Kelantan.

States in East Malaysia showed the most worrying results. There, the already low psychiatrist-to-population ratios recorded in 2013 dipped to barely marginal levels in 2017. In Sabah, psychiatrist-to-population ratios shrunk from 0.7 to 0.11 psychiatrists per 100,000 population while in Sarawak, the reduction was from 0.2 to 0.18 psychiatrists per 100,000. These ratios reflect a critical undersupply of psychiatric manpower available to serve the mental health needs of the population. Critically, these states had recorded some of the highest prevalence rates of mental health problems in the 2015 National Health and Morbidity Survey (42.9% prevalence in Sabah and 35.8% in Sarawak)

More shockingly, from 2013 to 2017, no psychiatrists were available to serve the Labuan population, signalling that population groups here have been severely underserved in terms of access to public mental health services.

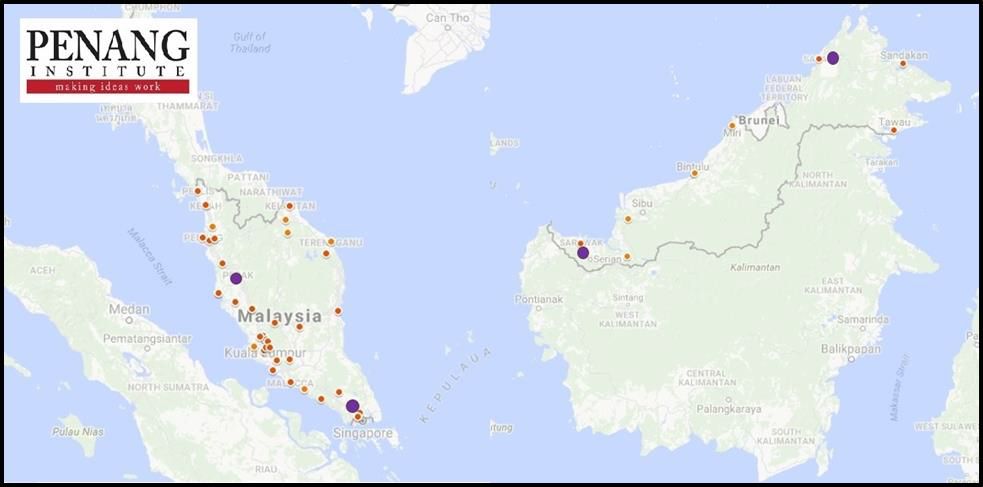

On top of manpower shortages, the distribution patterns of psychiatric services across government hospitals is also uneven. Based on information taken from the Health Ministry’s Specialty & Subspecialty Framework for Ministry of Health Hospitals Under 11th Malaysia Plan (2016-2020) report, a majority of specialist hospitals providing psychiatric services are geographically skewed towards urban centres, leaving rural areas and populations in East Malaysia underserved.

Figure 3: Distribution of Mental Health Services in MOH Hospitals, 2016 [5]

*Smaller red dots represent specialist hospitals. Larger purple dots represent psychiatric hospitals.

Source: Specialty & Subspecialty Framework for Ministry of Health Hospitals Under 11th Malaysia Plan 2016 report; author’s own derivations.

(ii) Clinical Psychologists

While the statistics on psychiatrists are worrying, the representation of clinical psychologists in public healthcare is even more troubling.

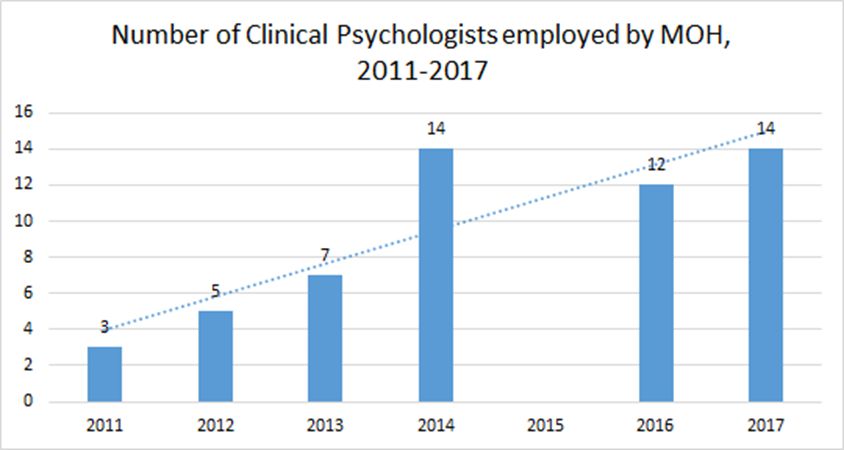

According to the report, the number of clinical psychologists across all government hospitals numbered just 14 in 2016. This shortage has been a chronic problem for many years. In 2011, for example, there were just 3 clinical psychologists serving in government hospitals across the entire country. While the numbers have risen since then, the rate of increase has been extremely marginal, going from 3 to 14 over the span of six years.

Figure 4: Number of Clinical Psychologists employed by MOH from 2011 to 2017

Sources: Ang, “Current Perspective in Mental Health”, 3rd Asia Pacific Conference on Public Health, 14 Nov 2011; Ministry of Health Malaysia Country Profiles 2015 Malaysia Report; ASEAN Mental Health Systems report 2016; Parliament of Malaysia, 2017

In government hospitals, the critical shortage of clinical psychologists means that their services are spread very thinly. Up until 2016, their numbers were too low to provide services to each state in Malaysia. Moreover, out of the entire mental health workforce, clinical psychologists make up the smallest group of providers and their ratios are abnormally low compared to other groups.

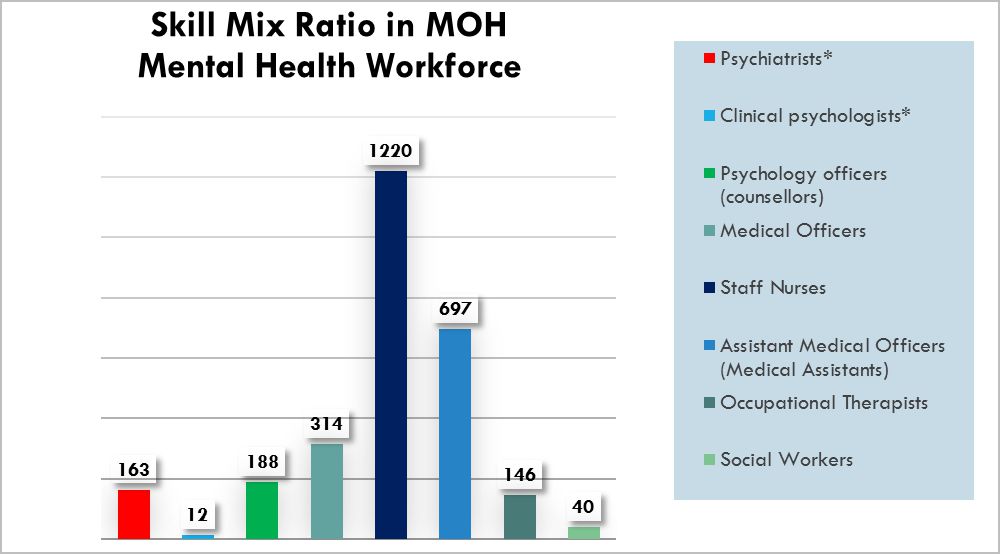

Figure 5: Skills Mix in the MOH’s Mental Health Workforce in 2016

Source: ASEAN Mental Health Systems Report, 2016

*The figure given for psychiatrists in this report contradicts the figure given in the Speciality & Sub-specialty Framework of MOH Hospitals under the 11th Malaysia Plan (2016-2020) report, where the number of MOH-employed psychiatrists for the year 2016 is given as 190. The reason for this contradiction is as of now unclear to the report author.

According to data from the ASEAN Mental Health Systems report, clinical psychologists made up the lowest proportion of all categories of government-based mental health providers in 2016. By share, they constituted 0.04% of the entire workforce, or 12 of out of 2780 workers. Merely 12 clinical psychologists were working in government healthcare facilities, compared to 163 psychiatrists, 188 counsellors and 146 occupational therapists. For every one clinical psychologists, there were as many as 14 psychiatrists based in public healthcare.

These shortages mean that certain states and rural areas are underserved in access to public mental health services. Undue strain is placed on the existing mental health workforce to deliver care to the mentally ill.

2. Expensive treatment charges in the private sector

Beyond government mental health services, the report also outlined challenges of seeking treatment for mental health in the private sector, where fees tend to be prohibitively expensive.

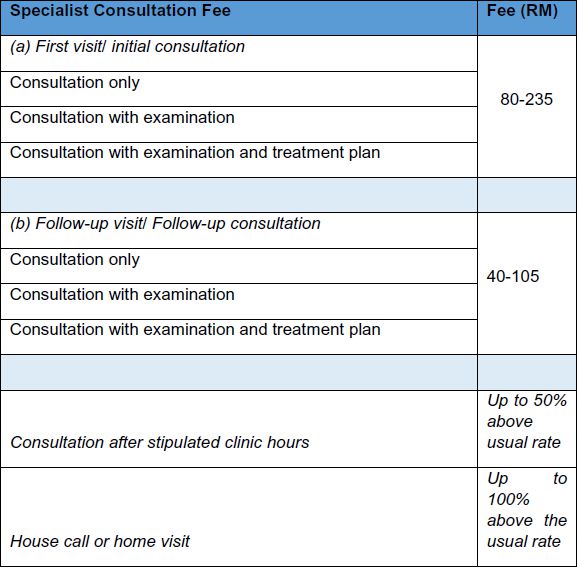

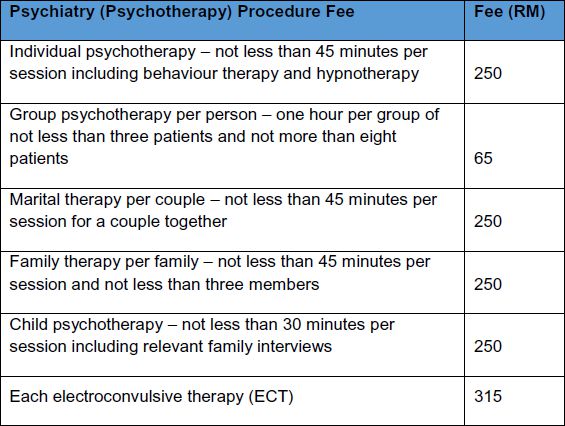

Although the Private Healthcare Facilities and Services Regulations 2006 provides an official medical fee schedule [6] to regulate private professional fee charges, it is common practice for many private specialists to charge for their services at a higher rate than the stipulated maximum ceiling of RM 250 (for psychotherapy sessions) and RM 235 (for specialists i.e. psychiatrist consultations), according to the report.

Table 1: Fee Schedule showing maximum chargeable fees for private medical specialist consultations and procedures

Source: Private Healthcare Facilities and Services (Private Hospitals and Other Private Healthcare Facilities) (Amendment) Order 2013 [Regulation 433], p. 94

Table 2: Fee Schedule showing maximum chargeable fees for various kinds of psychotherapy sessions in the private sector

Source: Private Healthcare Facilities and Services (Private Hospitals and Other Private Healthcare Facilities) (Amendment) Order 2013 [Regulation 433], p. 130

The blow of these high treatment costs may be softened if patients were able to purchase personal health insurance cover for mental health. However, as highlighted in the report, private insurance companies in Malaysia currently exclude coverage for mental health treatment from their medical insurance policies.

Moreover, besides personal health insurance, a majority of employer-sponsored health insurance (commonly referred to as “employee medical benefits”) which are offered by larger multinational organizations, also does not provide cover for mental health treatment for employees, since these plans are purchased from the same private insurance companies that sell personal health insurance to individuals. While the government’s social health insurance scheme for workers (SOCSO) does provide mental health benefits, these are largely limited to outpatient treatment at SOCSO-approved panel clinics and government hospitals, and it is much harder to file claims against charges for private treatment.

From an access standpoint, the non-inclusion of mental health coverage in insurance policies limits private healthcare to those who have the means to pay out-of-pocket, namely the upper middle classes and wealthier groups. Meanwhile, the poorer groups are excluded.

3. Stigmatization of mental illness

Aside from systemic and financial barriers, the report also highlighted stigma against mental illness as a significant deterrent to seeking help for the mentally ill.

In particular, the report highlighted prevailing attitudes of discrimination in the workplace, specifically employers’ reluctance to hire and retain employees with mental health conditions.

It was argued that such attitudes perpetuate a ‘vicious cycle’ where, on one hand, job seekers with pre-existing mental health problems face major barriers to gainful employment, while those who develop mental health problems as a result of existing work-related stress will conceal their problems for fear of damaging their careers, which only leads worsened health conditions.

On the subject of stigma within the wider society, based on a survey of secondary research literature, it was also found that in Malaysia, many cultural and ethnic narratives associated mental illness with a personal moral deficit or a lack of religious piety. In a more general sense, there is also a tendency to label persons living with mental illness as being weak and unable to cope. Over time, these negative views perpetuate actions of social exclusion and discrimination, prompting the mentally ill to self-blame and avoid disclosing their conditions out of fear of labelled as being ‘crazy’.

4. Policy recommendations

In view of these barriers, Penang Institute recommends several public policy approaches to improve access to mental health services in Malaysia. While detailed recommendations have been laid out in the report, a summary of key steps is as follows:

I. The Ministry of Health needs to build greater human resources capacity in the healthcare system and the wider community via the following measures:

a) increase the number of local psychiatry and clinical psychology programmes in local universities and create more incentives for medical students to pursue these careers.

b) increase the number of clinical psychologist positions in public hospitals, bearing in mind that hiring opportunities for this group are currently limited

c) equip GPs in primary care to detect and provide basic services for patients presenting with symptoms of mental illness, and to provide referrals to hospitals in cases where specialist care is required (this may be achieved through structured training sessions led by psychiatrists and psychologists)

d) develop a range of non-clinically trained (lay) mental health workers to deliver basic mental healthcare within the community e.g. NGOs and volunteer groups.

II. Introduce coverage for mental health treatment in private and social health insurance policies

a) insurance companies should start to include basic cover for mental health treatment in their medical plans. The government should also aim to include mental health coverage into the forthcoming Voluntary Health Insurance Scheme that has been slated for 2018.

b) to facilitate the process of underwriting policies and evaluating risk, the Health Ministry and private research entities must undertake greater research into mental illness burden in Malaysia, including factors affecting vulnerabilities and risk of developing mental illness, economic and social costs and treatment service outcomes (to know the difference that treatment is making).

III. Encourage greater recognition and acceptance of mental illnesses as valid health conditions and remove stigma barriers through intensive and effective mental health advocacy

a) Government and various mental health NGOs such as the Befrienders group and the Malaysian Mental Health Association (MMHA) should collaborate to host public engagements and workshops. Aside from mental health professionals, such events feature the voices and experiences of people who have lived/ are living with mental illnesses, as well as caregivers, so as to lend greater authenticity.

b) Universities, schools and workplaces should encourage and promote mental health literacy as part of the

cultural norm within their respective settings. This may be achieved through appointing committees that are specifically tasked to carry out relevant activities and programmes related to mental health, and encourage greater open discourse. Acts of discrimination (such as those observed among employers) may also be meaningfully addressed by increasing the levels of mental health literacy and awareness through these measures.

[1] This report was prepared by Lim Su Lin, policy analyst at Penang Institute in KL. She can be reached at sulin.lim@penanginstitute.org. The full report is available for download at www.penanginstitute.org

[2] Due to a paucity of publicly available data, national psychiatrist-to-population rates for the years 2012, 2014 and 2015 could not be calculated.

[3] The WHO Mental Health Atlas Project was designed to collect and disseminate data on mental health resources such as policies, plans, financing, care delivery, human resources, medicines, and information systems in the world. The project started in 2001 and the data was updated in 2005, 2011 and 2014. For 2014, country data was analyzed and reported both by WHO region and by World Bank income group. For the section dealing with availability of human resources, reporting by income group is more informative and comprehensive, hence this paradigm was chosen as an analytic framework for this paper. The full WHO report may be found at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/178879/1/9789241565011_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1

[4] The apparent high psychiatrist-to-population ratio in Putrajaya may be skewed by its small population size (relative to other states). In terms of actual numbers, the report found that the numbers of psychiatrists serving in Hospital Putrajaya was at the lower end of the distribution range of these mental health professionals across all public hospitals in 2017.

[5] The map was originally generated using the Google MyMaps custom mapping tool. Information on the names of hospitals providing psychiatric services was extracted from the Specialty & Subspecialty Framework for Ministry of Health Hospitals Under 11th Malaysia Plan 2016 report. The exact locations of these hospitals were then transferred into visual format the using the mapping tool.

[6] The first private medical professional fee schedule was officially laid out in 2002 under the Private Healthcare and Facilities Act and enforced by its 2006 regulations, under the 13th Schedule. In 2010, the Ministry of Health carried out a review of the fee schedule and approved a 14.4% increase in maximum chargeable fees for the private medical profession. This fee revision was approved by the Cabinet in 2012 and came into force in 2014 as Regulation 433.